A Ku Klux Klan initiation ceremony in Miami, 1922

© Bettmann/Getty Images

One of the most jarring things about the Ku Klux Klan is the silliness of their rituals and titles, their Exalted Cyclopes and Grand Titans of the Dominion; their Klokards, Kludds, and Kligrapps; their bed-linen costumery and blindfold initiation rites. How maddening it is that pure hate should make as a vehicle the world’s dumbest secret society, a fraternity as written by Monty Python. An early history of the Klan co-authored by one of its founders, John Lester, claimed that the first Klansmen were simply bored young men amusing themselves in Pulaski, Tennessee, during “a period of enforced inactivity” after the Civil War. They were just kidding until they weren’t. The Ku Klux Klan moniker was “mysterious because meaningless,” and its “weird potency” forced them to “harmonize” with it: “Let the reader pronounce it aloud. The sound of it is suggestive of bones rattling together!”

I don’t hear the bones—it sounds to me like a cat retching—but the idleness comes through, the noise of disaffected men with too much time on their hands. Their parody of ceremony became the real thing, shot through with bigotry and violence. You’d think it would take some doing to infiltrate today’s Klan, given its self-seriousness and paranoia. Surely a hate group with roots deep enough to have survived multiple eradications would have an elaborate vetting process. True to its roots, though, the modern-day Klan still comprises bored guys looking for buddies. If you’re tall, white, and male, and you can bench four hundred pounds, and you used to be an Army sniper, you can more or less walk right in, as Joe Moore discovers in White Robes and Broken Badges (Harper, $32), the story of his yearslong double life as the FBI’s man inside the so-called Invisible Empire.

In 2007, having been honorably discharged after eight years of service, Moore was living near Gainesville, Florida, when the FBI tapped him to become a “confidential human source,” their admin-chic term for an informant. His Army training meant that he reliably noticed how many stairs he’d climbed and whether doors opened in or out. The agency knew little about Klan activity in the area except that there was some; Moore’s handler, a splenetic man with a perpetually packed lip, could say only that a nearby Klansman was advertising a rifle for sale. Visiting the man’s house, Moore noted a front door made of steel, reinforced concrete walls, a vault full of guns, and three backyard shooting ranges: hallmarks of the bunker mentality. And yet Moore passed muster. After he called the man “sir,” flashed his Army credentials, and sounded a casual dog whistle (“I’m disgruntled with the way things in this country are going. . . . I just want to be around people like me”), his white robe was as good as in the mail. The feds marveled at his progress, fitted him with a wire, and eventually paid him a “modest stipend” for sending him into scenarios where a stray glance could lead to his execution.

Moore had broken into a north-central Florida klavern (Klanspeak for “chapter”) of the United Northern and Southern Knights. His naturalization (Klanspeak for “initiation”) involved being led into a dark room with a black pillowcase over his head and accoladed with a broadsword as he swore to “uphold the purity of the white race.” A cross of fourteen candles burned in front of him. He became Brother Joe, and began hailing his fellows with a hearty “KIGY!” or “KLASP!” (“Klansman, I greet you”; “Klannish loyalty, a sacred principle.”) The Klan as he knew it was a men’s social club whose “prayer meetings” gave them cover to spout shibboleths and foment rebellion. Senator Barack Obama was about to secure the Democratic presidential nomination, and his ascent occasioned facile remarks “about a Black man in the White House.” As he approached victory in 2008, “shoulders stiffened, voices lowered, and the talk turned more ominous,” Moore writes. He was enlisted as one of the hit men in a plot to ambush Obama’s motorcade in Kissimmee, Florida. Klan contacts at the DMV and in local law enforcement could provide inside information and “clean paper” for vehicles.

Moore foiled this plot and others just as menacing, and when his position in the klavern began to seem precarious, he squeezed his way into a second one, in nearby Bronson, biding his time until he’d gathered enough intelligence to indict the major players. His heroism is indisputable. A flag-waving foreword by Representative Jamie Raskin positions the book as a primer on domestic terrorism, the methods and mindsets that led to January 6. I can’t decide whether Raskin’s rhetoric is overblown or not. The events recounted in White Robes feel antiquated. Moore’s years in the Klan coincided with the explosion of right-wing internet culture, but the conspiring he witnessed was dumbfoundingly analog—white supremacy as retail politics. While 4chan edgelords sharpened their blades, frog-marching Pepe toward infamy, the Florida Klansmen hosted barbecues and convened in Dollar General parking lots. They maintained an 800 number and made inductees sit for a written exam. But their hatred was no less virulent for its being mired in the past. One Klansman took Moore to his backyard bunker to show off his incinerator: “My own personal crematorium. . . . Leaves nothing behind but teeth.”

By 2014, Moore had attained the rank of Grand Knighthawk and sometimes struggled to keep himself in view. He had been sexually abused as a child, and the book’s richest sections describe the bulwarks he erected in his mind to stay sane undercover. He donned the same ball cap whenever he became the other Moore and, in the long term, pictured himself climbing a ladder toward total transformation. The rungs had abstruse titles like “Shadows” and “Gray Man.” Driving to Klan klatches (a word they’ve never embraced, for some reason), he listened to Guns N’ Roses’ “Ain’t It Fun” on repeat or, to ground himself in “the man I really was,” considered his Christmas shopping.

White Robes might sound like redneck noir, but its milieu is far from the Florida of your Carl Hiaasens and Jimmy Buffetts, and Moore’s prose, even with the help of a co-writer (Jon Land), sometimes approaches the torpid. “The three amigos became the way we referred to our targets internally,” he writes, “drawn from the comic film of the same name, starring Steve Martin, Chevy Chase and Martin Short.” And yet this dispassion seems an authentic expression of all he endured—not just in his childhood and in the Klan, but also at the hands of the FBI, which left him twisting in the wind for years as his four cases awaited trial. (All of them earned convictions in the end.) The bureau resettled him and his family at random, seized most of their property, tanked their credit ratings, and refused to level with him about what the future might hold. During his own “period of enforced inactivity,” Moore spent his days puttering around a two-bedroom apartment and watching his son play arcade games at the Jacksonville Dave & Buster’s, panicking whenever one of the consoles said game over.

The four pastors at the Circle of Hope church also dedicated themselves to stamping out racism. Like Moore, they found that the process reshaped their lives, shearing away much of what they’d taken for granted, leaving them lopsided and confused. Eliza Griswold spent about four years among the pastors and their congregations in Philadelphia and New Jersey to report Circle of Hope (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $30), which sees the church buffeted by the winds of change—in this case, COVID, queerness, and anti-racism, that trifecta of latter-day sectarian unrest. Circle of Hope begins the book as a thriving if contradictory exemplar of progressive evangelicalism; by the end, the circle is broken, the crowds have thinned, and churchgoing in America seems an anemic thing, close to neither God nor country.

Circle of Hope was established in 1996 by Rod and Gwen—as luck would have it, their last name is White, and so were most of their parishioners. For years no one batted an eye at this (or at least no one with a platform did). The Whites, once Californian commune dwellers, forged a new church that met in warehouses and that styled itself a “rebel outpost,” where Rod preached in jeans with a music stand for his lectern. Technically they were Anabaptists, but no one wanted to dwell on denominational schisms; their gospel was one of radical love and forgiveness. They hosted punk bands and raised a generation of teachers and social workers. Circle wasn’t insulated from politics but was above them. No party could build the Kingdom of Heaven, though Rod did allow that Ronald Reagan might be the Antichrist. He and Gwen wanted to sever evangelicalism from capitalism. Their son Ben, one of the four pastors—two men, two women—who succeeded them, described the church’s strategy as invasive separatism. Sometimes visitors didn’t even realize they were attending church. (There’s a certain kind of Christian who really enjoys having Jesus pop out of a trapdoor.) Church members called South Jersey “the ruins of empire” and, on Easter Sunday, Gwen “smashed chocolate Easter bunnies with a meat tenderizer and ripped the heads off marshmallow Peeps,” Griswold reports. Circle Thrift, the church’s secondhand store, turned a handsome profit even after it was robbed by gunmen multiple times.

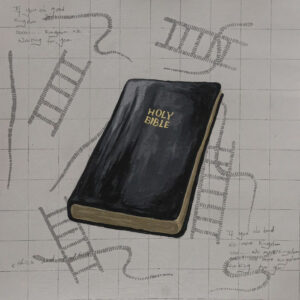

Objects and Conversations II (The Bible), by Ameh Egwuh © The artist. Courtesy Rele

Rod envisioned Circle as a church without hierarchy—he called its org chart “the Amoeba of Christ”—but everyone treated him like the man in charge, creating what Griswold calls “a tyranny of structurelessness.” Ironies emerged. Despite Rod’s staunch opposition to capitalism, he subscribed to a church-growth ideology that explicitly invited pastors to treat their vocation as a business. And it worked: at its peak, around 2016, Circle of Hope attracted about seven hundred worshippers to its services. Some of them noticed that the congregation didn’t come close to reflecting the racial composition of Philadelphia or the country. Others saw that Circle’s openness didn’t extend to gay people, or even to women who wanted divorces. In seeking a progressive agenda that somehow never aligned with secular trends, Circle was chasing a chimera. To some extent, its pains were intrinsic to Anabaptism, which stands apart from worldly culture and practices shunning, also known as “the ban.” By the time the pandemic hit, Rod had had one foot out the door for years, and Circle’s new leaders were racing to catch up to the times. A group that believed that “dialogue is our heartbeat” was now having stilted conversations like this one:

Bethany Stewart asked Rod if she and her fellow activists on the Circle Mobilizing Because Black Lives Matter compassion team could write prayers for the church website. Rod said no. Circle didn’t need prayers for Black History Month, he’d told her, since church teachings were already “naturally anti-racist.”

Hiring a DEI consultant would be a mistake, Rod felt, because such consultants “lived off the fat of capitalist empires,” Griswold writes. But it was he who’d first befogged the church with the language of consultancy, energizing “team members” as if he presided over a Walmart. The church brought in a consultant anyway, but he soon quit, so embedded were the Whites and their whiteness.

A circle ends where it starts: not the best outcome for hope. It takes enormous courage to open your life to a journalist, all the more so when you’re supposed to be doing the Lord’s work. All of Griswold’s principals, to their credit, stuck with her even when it became clear that their church was in extremis. Their commitment to revealing the struggles of their faith, no matter how homely, seems to me the most nakedly Christian thing about the book. Griswold—whose father, once the presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, consecrated the denomination’s first openly gay bishop—treats the pastors generously, though gingerly, constructing from their lowest moments an affecting study of sacred life in sacrilegious times. What brings people to church today? I didn’t know before and now I don’t know even more, but Circle of Hope brought the dilemma alive.

Lonk sheep, c. 1960 © Barnaby’s Studios Ltd./Mary Evans Picture Library.

Maybe my spiritual practice shall be to become a sheep, to conduct my life in the most densely populated city in America as if it were an English farm. The epithet “sheeple”—wielded against joiners of all stripes, Christians and Klansmen alike—is unfair to the animals. Rosamund Young writes in The Wisdom of Sheep (Penguin Press, $27) that all sheep are different, but it takes time and patience to discover their individuality. You’ve got to embed. Don’t appear too eager. Let them show themselves to you. It’s kind of like being an FBI informant.

This is Young’s follow-up to The Secret Life of Cows, a second series of vignettes about her life at the impossibly bucolic Kite’s Nest Farm, in the Cotswolds. “I started a notebook-cum-diary and found to my surprise that I thoroughly enjoyed recalling and recording daily farm events,” she writes. I don’t buy that “to my surprise” for a minute, but I’ll let it slide, because I thoroughly enjoy reading about daily farm events. They enter the bloodstream like benzodiazepines. A rougher comparison might be to pornography, and I mean this favorably. Young’s anecdotes entrance you within seconds; you can use them compulsively to self-soothe, and you can skip around with no fear of missing the good parts: the “goldfinches swaying on the thistledown” anecdotes or the ideal place to rest your forehead when hand-milking a cow (on “the soft piece of flesh that arches over the udder”). There are, I’m sure, sound arguments against the cynical citizen’s tendency to fetishize rural life, not least of which is the fact that those of us reading about farms almost never go on to work the land. Still, imagine being able to say this about yourself: “There is a grainy photograph of me aged around two years, bottle-feeding a lamb in my grandmother’s orchard.” The words “grainy photograph” alone could add years to your life.

European goldfinches from Archibald Thorburn’s second edition of British Birds, Vol. 1, 1925 © Natural History Museum, London/Bridgeman Images

So I took it all in. The meadows, grasses, wildflowers, “starry-eyed tormentil and its cuddle-carpet of bright, tight new growth.” The tale of the sheep who, during a heavy rain, made room in their shed for a fox cub. The kindly ewe who licked a premature lamb (not her own) until he radiated with self-assurance and belonging. The varieties of headbutting that form a lamb’s language of salutation. Reading Circle of Hope, I’d rolled my eyes when one of the pastors said she’d been called to “care for the flock.” Then I turned to Young: dozens of pages of gamboling lambs, bees buzzing around fence posts. “The sheep walk towards some people,” she writes, and they believe in predestination. “You are either one of the chosen or you are not.” I want to be among the elect.