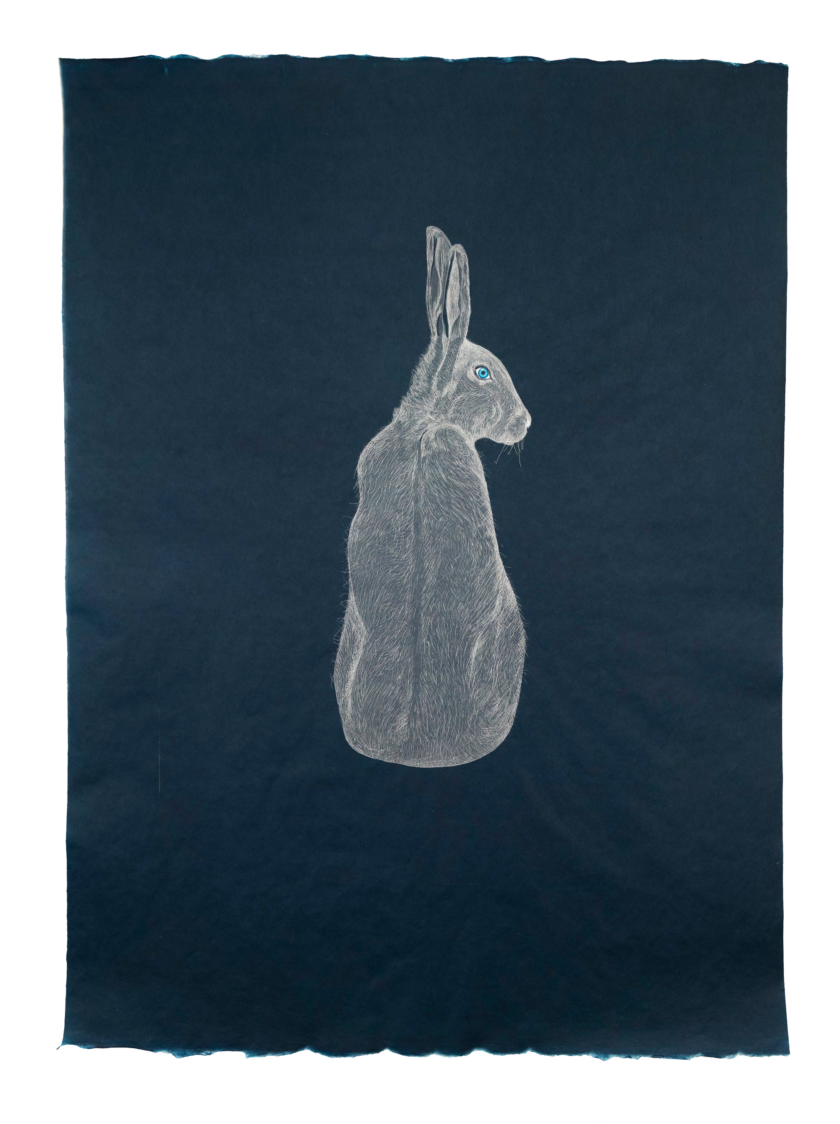

Hare (Blue Eyes), by Valerie Hammond © The artist. Courtesy Planthouse, New York City

Had I known that Aesop’s fables were so unhinged, I would’ve turned to them long ago. Having encountered your standard-issue tortoise and hare, boy who cried wolf, town mouse and country mouse, et al., I assumed the other seven-hundred-odd stories would contain the same simplistic finger wagging. Well, I was wrong. Robin Waterfield’s Aesop’s Fables: A New Translation (Basic Books, $30) renders them in all their feral, fatalistic glory—bursts of Hobbesian asperity with dubious, sometimes conflicting, morals. To live is to struggle, they say, and if you’re strong, rich, or incorruptible, you may struggle less, but perhaps not. Take out the talking animals and it’s hard to see why anyone felt that children should read these things. The Greeks, Waterfield suggests, intended them for adults—and for good reason. I wince to think of a kindergarten classroom listening attentively to “The Wasp and the Snake”:

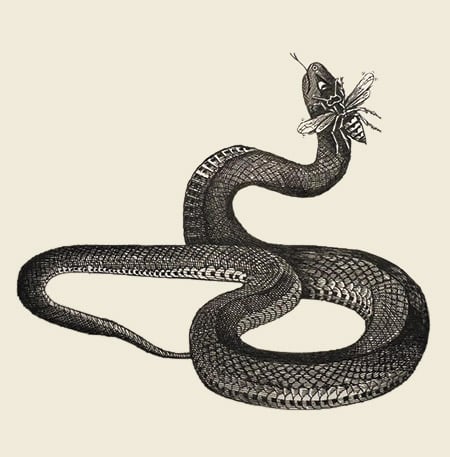

A wasp settled on a snake’s head and stirred him to fury by constantly stinging him. The snake was in agony, and there was no way he could defend himself against his enemy, so he laid his head on the ground under the wheel of a cart and killed himself along with the wasp.

There you have it, kids. An ancient precursor to the kamikaze pilot and the suicide bomber, passed down through oral tradition. Likewise, the moral of “The Eagle and the Crow,” in which two birds conspire to drop a tortoise on a rock, is that “it’s impossible to be sufficiently armored against powerful people.” It ends like this: “The tortoise, despite the boon granted it by Nature for its defense, was no match for the two together and died a wretched death.”

The Snake and the Wasp, by John Vernon Lord © The artist

Wretched death permeates the fables, which see animals torn to shreds, drowned, smothered, choked, savaged, and gobbled up. Humans are crucified, beat over the head with melons, and decapitated. Even the gods are frustrated and deceived. Many of Aesop’s characters use their dying breaths to chastise themselves for the error of their ways. “What an idiot! I had no idea what I was doing!”; “How pathetic I am!”; “We deserve to have been slaughtered one by one!” An eagle shot by an arrow says, “As if the pain weren’t already bad enough, I’m being killed by my own feathers!”

Why a new take on the fables, and why now? Life is still a muddle and a slog, which is justification enough, I guess. Mercifully, Waterfield, an independent scholar who has translated Plutarch, Plato, and Aristotle, makes no heavy-handed bid for the continuing relevance of the stories, what Aesop can teach us today, etc. His introduction finds no fault with previous translations, of which there are many. He seems to have undertaken this project for sport, or to pass the time—he lives, apparently, “on a small olive farm in southern Greece”—and I admire him for that, all the more for his not translating every fable, just a representative batch of four hundred. He reminds us that little is known about their purpose or provenance. Jokers and politicians found a certain currency in them; the historical Aesop may or may not have existed. According to legend, he was a slave known for his ferocious ugliness: “potbellied,” as one source reputes, “misshapen of head, snub-nosed, swarthy, dwarfish, bandy-legged, short-armed, squint-eyed, liver-lipped—a portentous monstrosity.”

Bringing the fables into “readable, modern English,” Waterfield has given them a freshness and frankness that makes them all the more discomfiting. This is most evident in the concise scene setting of their opening lines. “The hares, painfully aware of their cowardice, decided to hurl themselves to death off a cliff.” “A snake slithered up to a farmer’s son and killed him.” “A woman who had just buried her husband was sitting by his grave shedding sorrowful tears. A plowman saw her and wanted to have sex with her.” He’s more candid than previous translators. “The Hyena Couple,” one of a few fables so bawdy that it wasn’t available in English until some decades ago, contains a passage that Waterfield renders as follows: “Once a male hyena forced a female to have anal sex, and she said, ‘Go ahead, my dear! Don’t stop! But just remember that before long you’ll be the one at the receiving end.’ ” Other English versions use “an unnatural sex act” or “treating a female badly” where Waterfield opts for “anal sex.” It’s the little things.

Among the murderous ferrets and bees, the frogs, bulls, and bramblebushes, the wolves, foxes, and fishermen, I felt unimproved and grateful for the comparative softness of my civilization. There are, to be sure, moments of beauty amid all the fabulous dying. One fable tells of men who, having discovered song,

were so ecstatic with pleasure that they were too busy singing to bother with food and drink, so that before they knew it they were dead. They were the origin of the race of cicadas, whom the Muses granted the gift of never needing any nourishment after they were born; all they do is sing, from the moment of their births until their deaths, without eating or drinking.

This reverie doesn’t last. In another tale, the cicadas persuade a donkey to sustain himself on a diet of dew like they do. The ass dies of starvation. The moral: “people who want to be other than what they are not only have this desire of theirs thwarted but meet with complete disaster.”

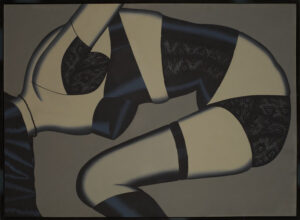

Les Wexner, the billionaire who brought us such retail experiences as Abercrombie & Fitch and Bath & Body Works, was once dubbed “The Merlin of the Mall,” but he may have been its Aesop too. Wexner believed that “a brand is a story well told.” His most lucrative achievement, Victoria’s Secret, was a work of ruthless fabulism whose moralizing shaped, supported, and lifted a generation’s anxieties about the female libido. In Selling Sexy: Victoria’s Secret and the Unraveling of an American Icon (Henry Holt, $29.99), the fashion journalists Lauren Sherman and Chantal Fernandez study the hauteur and ambition undergirding “the intimates market”—a phrase whose contradictions summarize the business of lingerie. Few things are less intimate than a market, and fewer still are less marketable than true intimacy.

Victoria’s Secret began in the late Seventies as a chichi boutique in Palo Alto, where its founders, Roy and Gaye Raymond, launched a mail-order catalogue for what they called the Xandria Collection, offering vibrators and “sexual aids” without the seedy clichés of the red-light district. Similarly, the Raymonds felt that tasteful surroundings (oriental rugs, antiques) would make it easier for women to shop for unmentionables like lace teddies. “Welcome to my album of silk and satin delights,” wrote “Victoria” in the shop’s inaugural catalogue, which soon found favor among prison inmates for its photos of women with hot-pink lips and visible pubes. Gaye told the local news that Victoria was a real woman, a self-assured British executive they’d met aboard the Orient Express. Roy, intrigued, had asked her what her secret was. Her electrifying reply: “Fantastic lingerie.”

Waiting Lady, 1972, acrylic on Masonite in an artist-painted wood frame, by Christina Ramberg, whose retrospective is on view this month at the Hammer Museum, in Los Angeles. Collection of Anstiss and Ronald Krueck, Chicago. Courtesy the Estate of Christina Ramberg and Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago

Her other secret was that the Raymonds had made her up. Victoria was an aspiration, a way of gentrifying sex. “We are not selling items for women who stand in doorways with a come-and-get-me pose,” Roy said in 1981, describing much the way many future Victoria’s Secret models would appear. The next year, facing bankruptcy, he sold the business to Wexner, who moved its headquarters to America’s sultriest city (Columbus, Ohio) and set about coarsening it toward ubiquity. The catalogue now employed male models as well—“Stop the shoot! Got a woody!” one of them remembers shouting—and the stores, which spread nationwide, sold shoddier merchandise. Sidelined, Roy watched as Wexner turned his sumptuous lingerie concern into a juggernaut of two-for-one panties, available a dial away at 1-800-HER-GIFT. In 1993, with Victoria’s Secret raking in more than a billion dollars in revenue, Roy jumped to his death from the Golden Gate Bridge. Not long afterward, Gaye took their teenage daughter to Victoria’s Secret in search of a silk chemise. “We don’t carry silk,” they were told.

Under Wexner, the brand vacillated between extreme tawdriness and a mass-market reduction of “English manor refinement.” The result was a vaguely titillating incoherence in which luxury, sex appeal, and self-actualization were all interchangeable. The Victoria of the Nineties, developed for internal circulation in a “brand book,” had a full name (Victoria Stewart-White), a barrister husband, an English financier father, and a quick-tempered French mother who’d died in a car wreck. She owned a fifty-two-foot schooner called My Victoria and sunbathed topless. Her secret: “To look at life glamorously.”

The Victoria of the new millennium, by comparison, was American. She lived in Chicago and had a degree from Northwestern. She was unmarried, a “sensual young woman with good taste and a European sense of appropriateness”—which could mean that she had no issue with premarital sex or that she thought restaurants should close between lunch and dinner. Her bra size was 34C. The brand by then had adopted what it referred to as the “wheel of sexy,” a matrix of some twenty features—naughty, nice, extroverted, introverted, for me, for him, divas, ingenues—that represented “a corporatization of the feminine mystique,” Sherman and Fernandez write. The goal was to market something in every category, which led to the occasional tautology. When the brand proposed a new line of push-up bras called “Sexy,” some execs objected. Did this not imply that the other lines were unsexy? Wexner adjusted the name to “Very Sexy.”

Dirty, by Katie Butler © The artist. Courtesy Marrow Gallery, San Francisco

It seems like something of a miracle (and “Miracle,” be it known, was another line of Victoria’s Secret push-up bras) that any of this was appealing to women. Wexner had a sixth sense for what he called “patterning”—trendspotting as a god might practice it, from a Learjet at cruising altitude. It didn’t require knowing what people wanted, only what could be mass-produced to address a collective, half-submerged, primal yearning, an exercise in distilling desires into shoppable moments. Wexner knew “the way colorful cotton underwear arranged across a countertop recalled the impulsive joy of shopping at a candy store,” Sherman and Fernandez write. At the height of grunge in the Nineties, he predicted that pencil skirts would reemerge because people were ordering martinis: “No one drinks martinis in flannel,” he said. A Victoria’s Secret exec remembered his “calling from a museum in Europe with the simple directive to ‘do something with angels.’ ” This is the essence of his genius. The hoary contents of the Louvre or Prado, poured through the strainer of his mind, yielded the clarion conviction that feathered wings would sell bras.

And they did, when they were affixed to supermodels. By the mid-2000s, the Angels had usurped Victoria’s role in the brand’s mythology. Commercials showed them visiting the North Pole and Mars, where, in a nod to 2001: A Space Odyssey, an alien hurled “the sexiest bra in the galaxy” skyward. Rupert Everett hosted their annual fashion show with some off-color jokes: “Security is tight, and so are the girls.” The brand at its zenith was convinced of its ability to make anything sexy, even 9/11, after which one of its models told the press, “This is about being a woman and being powerful and using your assets. It’s liberating, and I’m proud to be a part of the free world.”

Data II, by Nona Hershey © The artist. Courtesy Schoolhouse Gallery, Provincetown, Massachusetts

But Wexner knew the outer bounds of sexiness. He didn’t want Victoria’s Secret to promote safe sex, for instance, or to fund breast-cancer research. In the 2010s, the brand was knocked from its pedestal by the bralette, which was simple, comfortable, unadorned, one might say humane—and therefore unworthy of Victoria and her Angels. “You’re not getting fucked in that,” the head of marketing said. When Wexner relented and jumped on the bralette wagon, stores advertised them with the slogan “No Padding Is Sexy Now!” Soon afterward, it emerged that Wexner, the unlikely Midwestern arbiter of allure, had entrusted much of his fortune to a convicted sex offender named Jeffrey Epstein. He resigned in 2020. Selling Sexy has a keen sense of the ironies in all this and of the shopping mall as the erstwhile spiritual center of American life. Wexner, of course, declined to be interviewed for the book. Participation isn’t sexy.

There’s a reason they called the store Victoria’s Secret and not Victoria’s Hiding Place or Victoria’s Privacy. The secret, the hidden, and the private are distinct categories, and the philosopher Lowry Pressly is tired of our conflating them. In The Right to Oblivion: Privacy and the Good Life (Harvard University Press, $35), he aims to wrest our sense of the private from “the myopic presentism of the technology industry.” He inveighs against the suggestion that “privacy is only of value for those who have something to hide,” which

forces us into lame replies like “everybody has something to hide” rather than saying what we ought to say: “Hiding is for those with something to hide!” Secrecy is for keeping secrets. Privacy is for something else.

Even having read his book, I struggle to articulate what that “something else” is, but I’m dead sure that it has nothing to do with iCloud data. It has nothing to do with anything, really. Pressly is committed to privacy that “protects, but also produces, oblivion”—not the abyssal kind, but a state of blithe, salubrious ignorance in which “there is no information or knowledge . . . only ambiguity and potential.” It’s privacy that involves passing your neighbors’ homes and accepting, without much further thought, that you’ll probably never know about their first kisses or whether they pour their bacon grease down the drain. Their depth, and your own, relies on your not knowing; the whole social fabric of the world depends on it; it is beautiful, it is profound, it is robust. Pressly’s attempts to define it more specifically are sometimes arcane, but he draws from a wealth of surprising sources: a motel-room Peeping Tom who left no trace; the moral panic that greeted early medical scopes; a German double murderer who, having served his sentence, sued for his right to be publicly forgotten. From these stories Pressly constructs a vision of private life that needs protecting. I thought of one of Aesop’s fables, “The Dog and the Reeds”:

It so happened that a dog wanted to take a shit where some bulrushes were growing, and one of the reeds gave him a good poke in the arse. The dog retreated a few feet away and barked at the rushes, but the one that had poked him said, “I’d rather have you bark at me from a distance than foul me from nearby.”

As the dogs of modernity encroach, we must be like the reeds and poke.