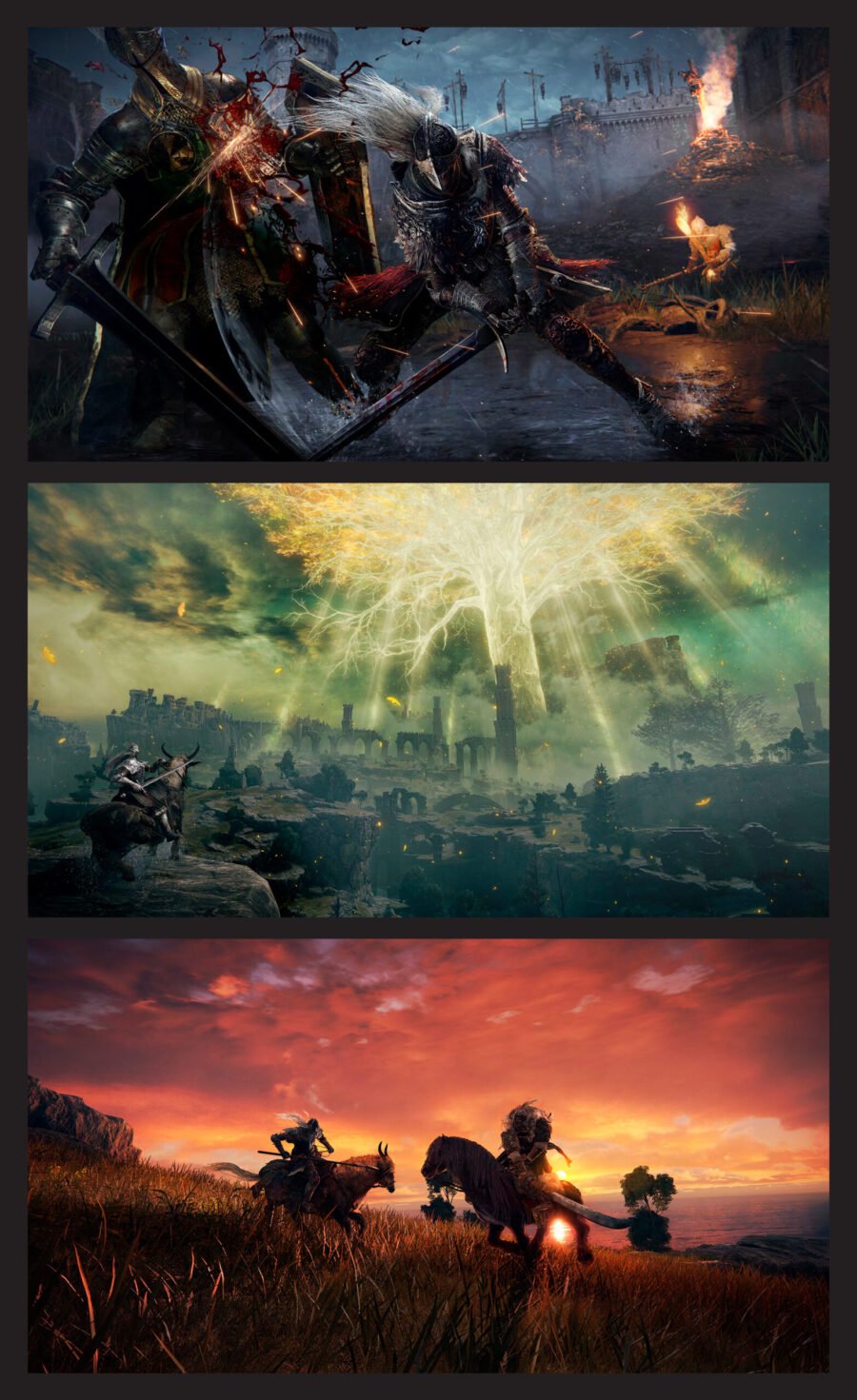

Stills from Elden Ring. Courtesy FromSoftware/Bandai Namco Entertainment/IGBD

Discussed in this essay:

Elden Ring, developed by FromSoftware. Bandai Namco. $59.99.

Elden Ring: Shadow of the Erdtree, developed by FromSoftware. Bandai Namco. $39.99.

Video games, even when played alone, have to be understood communally. Each game is a little different for every player—not just understood differently, as with other art forms, but literally different. Different things happen in them, big or small, as each player plays it in their own way, makes their own choices, provokes different outcomes. So the only way you can really come to know a game is by finding out how it went for other people, and by telling other people how it went for you. From every game that is dropped into the world, such accounts ripple outward: anecdotes, analyses, debates, and rumors, these days mostly online, in the form of wikis, Twitch streams, YouTube videos, and Reddit posts.

No games have demonstrated this more clearly, or more extravagantly, than the recent works by the Japanese studio FromSoftware—Demon’s Souls, the Dark Souls series, Bloodborne, Sekiro, and, most recently, Elden Ring. They are complex, idiosyncratic action games, at once dour and ridiculous, maddening and mesmerizing. Playing, you might find yourself guiding your sword-wielding warrior into battle against a giant dragon who throws lightning bolts at you while the soundtrack swells. Or you might send him creeping through a dark sewer, only to fall into a pit filled with giant googly-eyed lizards, choke on the black gas they emit, and lose an hour of progress. Each of these games has been accompanied by a frenzy of commentary and reaction. There are endless, sometimes vicious arguments over which of the games, levels, bosses, weapons are best or worst; over how their influence has changed the rest of the industry—or how it should. Thousands of videos document moments of surprise: people reacting to a boss discarding his robes to reveal his true identity, to a wall dissolving at a touch. Moments of triumph: someone beating the game without dodging; or someone using bongos as a controller, or brain waves, or Morse code; someone simply beating a boss, at last, however they can; someone, somehow, beating all the games, back-to-back, without ever being hit. Moments, above all, of failure: a relentless series of slapstick shorts, in which the punch line is always you died—crushed by a trap, lured off the edge of a cliff, incinerated by a dragon, slashed by some baffling, blade-wielding monstrosity, beaten up in a corner by a couple of raggedy soldiers. One might find failure more particular and sustained: after spending a few dozen hours trying to beat the final boss of Shadow of the Erdtree, the recent expansion of Elden Ring, Kai Cenat—a Twitch streamer so popular he accidentally caused a riot in Manhattan last year—consulted with a therapist about his waning confidence as the camera rolled.

Or matters might turn academic: emotive, hours-long retellings of the games’ stories; analyses of their architecture, symbolism, and art-historical inspirations; accounts of how playing them helped someone deal with depression, or understand “what it is to battle grief.” These are video games in the gamiest sense—violent, repetitive, grandiose, silly. In fact, they are probably the most influential video games of the past decade, inspiring a new subgenre of “Soulslikes” and changing how designers approach storytelling, level design, combat, and failure in all sorts of ways. But at times they can seem, for their tens of millions of players, more like a strange kind of interactive scripture to be pondered, parsed, defended, and used to understand the world.

They certainly didn’t start that way. The first, Demon’s Souls (2009), was developed with little oversight by a team led by a young designer named Hidetaka Miyazaki. Miyazaki knew his ideas for Demon’s Souls would seem unsalable, so he hid them from his superiors until it was too late to change the design. The game was released without much fanfare, and exclusively in Japan; it was exported to the West only after a few enterprising critics and fans got their hands on the game and raved about it. It sold slowly, then less slowly. The Dark Souls trilogy (2011–16) followed, along with Bloodborne (2015) and Sekiro (2019), and by now the Soulsborne games (as fans refer to them collectively) have sold well over eighty million copies. The newest and most ambitious, Elden Ring, was the second best-selling game of 2022—which, if it were a movie, would make it Top Gun: Maverick.

They are all, in a general sense, conventional action games. You control your character from a close third-person perspective and spend most of your time fighting. Most of the games are set in a horror-tinged version of Western high fantasy: there are knights and dragons, giants and monsters, swords and spells, and the occasional club made from an enormous, magical severed finger. (Bloodborne turns instead to Victorian horror, Sekiro to a fantastical sixteenth-century Japan.) As you fight, you acquire new weapons, increase your character’s abilities, and find more and bigger monsters to fight, until you reach one last enemy, kill him (or it), and the credits roll—the usual.

The closer you look, though, the stranger the games get. Where most action games want you to hurtle through them, all speed and momentum and ever-changing spectacle, the Soulsborne games are ponderous and frustrating. Your character moves slowly, and even minor enemies can kill you within seconds. You creep along—progress comes in dribs and drabs, earned through painful repetition. Where most video games try to seem vibrant and alive, hiding their simulated nature beneath as much movement and variation as they can, these make no effort to conceal the fact that the worlds they present are preprogrammed and artificial: enemies, though visually elaborate, move in clear, repeated patterns, and they often stand perfectly still when left alone. It is not an imitation of the complexity of real life but an intricate, hostile mechanism that creaks into action as the player approaches.

Many of the features of this mechanism—basic facts about how the game works—are kept deliberately obscure. The player is left to stumble about, guessing at things that any normal game would explain immediately. Why is my health cut in half after I die, but only sometimes? Why is there a number tracking my “Humanity” or “Insight,” and what does it do? (And what, for that matter, is my “Humanity”?) Why does my character just sort of flop to the ground when I try to roll? Large areas of the games—including several of the best in both Dark Souls and Elden Ring—are tucked away in hidden corners, and the games can be completed without your ever even realizing they exist.

With the exception of Sekiro, the games are also a peculiar mix of singleplayer and multiplayer: though you generally play by yourself, the games of other players bleed into yours if you are connected to the internet. Their translucent ghosts flicker into sight; bloodstains show where they have died and function as warnings, or comic relief—you might watch a ghost blithely run through the door to the next area, then come tumbling back through to die in a panicked heap at your feet. Messages left by other players appear in your world, offering hints, encouragement, jokes, or bald-faced lies. (There are also systems, intentionally a bit cumbersome, for entering other players’ games to help or attack them, and for inviting them to enter yours.)

Much has been made of the difficulty of these games—it has been criticized as exclusionary, lauded as a return to gaming’s roots, used as a selling point. (prepare to die, declared the slogan of the first Dark Souls.) But “difficulty” is an elusive concept, one word standing in for a number of ways in which a game can resist its players. The Soulsborne games are obtuse and unforgiving, cruelly willing to discard your progress—and waste your time. Each encounter is an invitation to panic and blunder, and be forced to repeat it. Especially in the earlier games, saving was heavily restricted, and progress could be easily lost—one brain-dead stumble can set you back an hour. But the bar to progress is not, in the end, so very high. Soulsborne games do not require great dexterity or reflexes, or the processing of large amounts of complex information, as some games do. They are a test, instead, of patience and understanding—of will, not skill.

Another way to put it is that the games can be, for the wrong person, or someone in the wrong mood, simply unpleasant. It is not always clear why one would want to spend one’s leisure time swearing at a screen, lost, stuck, dying over and over in the dark. More often, though, they provide something much more complicated: a paradoxical mix of joy and outrage, relief and despair. The repetitive drumbeat of failure, occasionally punctuated by success or disaster or revelation, batters you into a kind of gleeful serenity. Failure becomes funny, even soothing. The games are full of jokes at the player’s expense—traps and dead ends and carefully orchestrated aggravations. Game after game runs variations on the comedic setup of an enormous stone ball rolling at you down a slope, for instance. It’s there in the opening level of Dark Souls, to teach you about dodging, and about the game designers’ malevolence; then it appears again and again in more complicated arrangements. By Elden Ring such traps have become familiar, even comforting—until the moment when a boulder rolls past you, stops, and then rolls back, seemingly of its own free will, to crush you from behind. The only possible response is to laugh or give up.

Miyazaki has said that part of the original idea for Demon’s Souls was to get back to basics, to make a game “the way games used to be.” But his is a selective, even perverse memory of those olden times, with the gaps and limitations of earlier games turned into deliberate features, their accidents and oddities now ingrown, alien. Before there was so much information about them available online, video games often accumulated rumors—of secrets hidden at the edges of the map, mysterious features slipped into the code. FromSoftware deliberately cultivates those mysteries, demanding that players sort through rumors as they play. Back when games were still played mostly in arcades, they were usually based around a staccato interplay of repetition and progression—the faster a player failed, the sooner they could be lured into putting in more money. The Soulsborne games slow this rhythm down to a lingering, luxurious examination of failure for its own sake. They do not return to a previous simplicity but take a route through the old to the new.

Often this involves teasing out the emotional possibilities of game-design contrivances. For instance, in all these games, your character is notably smaller than the enemies you fight. Even other humans generally tower over you. Part of this is simply convenience: since the games are played in third person, a smaller player character makes it easier to see past them to the rest of the world, and larger enemies are less likely to be obscured in close-quarters combat. But it also means that the world itself feels more threatening and alien, the player more fragile, triumphs more tenuous and unlikely. The architecture often reflects this, with doors and stairways clearly made for much more massive beings than you.

The Twisted City, an illustration by Timothy Kelly. The artwork depicts a character of Kelly’s invention, “The Weaver,” in the Northern Limit, an unfinished level discarded early in the development of Demon’s Souls. Kelly’s work is included in the book Soul Arts, a collection of fan art curated by VaatiVidya and published by Tune & Fairweather. Courtesy Tune & Fairweather

Even more unusual is the games’ approach to storytelling—or, rather, the near absence of traditional storytelling. Though they have elaborate fictional worlds and complex plots, little of either is communicated directly. Instead, much of the narrative is concealed, and large parts are erased entirely. The player is tossed a few proper nouns and vague declarations (in Dark Souls, players are told that they are the “Chosen Undead” in the cursed land of “Lordran,” and must ring the “Bell of Awakening”; in Elden Ring that they are a “Tarnished” who has returned to the “Lands Between” to try to mend the “Elden Ring” after the “Shattering”) and dumped into the game. The traditional means of video-game storytelling—cutscenes, voice-over narration, and conversations with other characters—are present only in the most attenuated, enigmatic forms. The significance of what you’re told, and all the other details of the setting and story and your role in it, are scattered in a vast heap of hints and fragments: in the brief textual descriptions attached to weapons and items, in the few sparse interactions with other characters, in the visual details of landscapes, buildings, and enemies. These are all easy to miss if you aren’t paying attention. You could make it to the end of the game without any real idea of what is going on, let alone ever quite figuring out what a “Tarnished” might be.

Even if you are paying attention, it isn’t easy to piece it all together. Elden Ring’s story, especially, is complicated and ambiguous, and it often seems intentionally hard to follow. The Lands Between is a dense, deranged rendition of a traditional fantasy continent, its very name like a garbled machine translation of “Middle-earth”: rolling grasslands, misty forests, enchanted lakes, snowy mountains, deserts, castles, a magical school, even a volcano, all mashed together and filled with monsters. From shards of narration and other clues one can learn that it has been ruled—formed, deformed, and fought over—by a series of gods, demigods, and the even more powerful abstract forces that choose and empower them: the “Greater Will” holds sway, as shown by the enormous glowing “Erdtree” that looms over the world, and various “Outer Gods” lurk. Everyone you encounter is aligned in some way or other with one of them.

This history swarms with vexingly similar names: Radagon, Radahn, Rykard, Rennala, Rellana, Renna, Ranni, Roderika, and Rogier; Godfrey, Gowry, Godrick, Godwyn, and Gurranq; Margit, Morgott, Mohg, Marika, Miriel, Malenia, Millicent, Miquella, and Maliketh—many of whom are related to one another, only some of whom are human, depending on your definition, and some of whom turn out to be the same being under different names. (You meet—and kill—most of them by the end of the game.)

Piecing together an actual narrative around those names is not easy. You might wonder, for instance, about Marika. That she is the reigning deity of the Lands Between is fairly clear from the ubiquitous statues of her likeness strewn across the landscape and various scraps of narration. But other seemingly basic facts—how she is related to the other demigods, how she came to power, why she apparently set off the Shattering, an apocalyptic event that left the entire continent in chaos and a state of civil war—emerge only in stray lines of dialogue or a few seconds of gnomic cutscene, or are never answered at all. It’s not a narrative you simply “experience”: you either ignore most of it, or you go a little insane, poring over minute details and message-board speculation like a conspiracy theorist. Do eye colors have a deeper significance? (Yes, of course.) What’s up with all the giant fingers? (An essay in itself.) And what could it possibly mean that Marika (spoiler alert) is the same person as Radagon, her second husband, especially since they seem to have been on opposite sides of the Shattering? That baffling answer is revealed only if you use a specific spell in front of a specific statue, or through an otherwise extremely confusing cutscene near the end of the game, and itself requires further explanation that is never provided.

Everything comes that way: implicit, incomplete, out of order, deliberately unclear. Miyazaki has said that his approach to narrative was inspired by his childhood experiences reading Western fantasy novels, which he could understand only partially. (For Elden Ring he actually hired one of his favorite fantasy authors, George R. R. Martin, to help write the underlying mythology, which was then duly obscured.) It does have that feel—a few names and spots of clarity shining through a mist of uncertainty—but if anything, this understates how puzzling and enigmatic even fundamental events and concepts are in his games’ stories. It is impossible, really, for any individual player to piece everything together on their own, in a normal playthrough, and some major questions are left completely unanswered.

To unlock these mysteries, a large, energetic online community has devoted itself to combing through the games and compiling discoveries, theories, and counter-theories. Controversies can hinge on the exact meaning of a single phrase, on possible mistranslations from the Japanese original (was the Great Tree meant to be distinct from the Erdtree, or not?), on subtle details of costume and statuary. Unused material dug up in the code serves the role of apocrypha, illuminating, say, the possible significance of the God of Frenzied Flame through a storyline that was cut from the game before its release. A few of these explicators even make a living doing it—the most prominent, an Australian named Michael Samuels who posts under the name VaatiVidya, has pursued it as a full-time job since 2015; his YouTube videos, on subjects like “The Lore of Elden Ring’s Dragons” and “Elden Ring’s Demigods Explained!,” are slickly produced, often over an hour long, and viewed by millions.

Consulting such sources is the only way to get a solid grasp on the story: the shared exegesis, though external to the game itself, is integral to the experience of playing it. Marco Caracciolo, a professor of English and literary theory at Ghent University in Belgium, recently published a brief academic monograph about this odd way of telling a story, under the slightly cumbersome title On Soulsring Worlds: Narrative Complexity, Digital Communities, and Interpretation in “Dark Souls” and “Elden Ring.” These games engage in a form of “environmental storytelling,” he writes, that creates “an ‘archaeological’ mode of fandom, which denotes attention to environmental clues and an emotional investment in the material history of the game world,” and these online debates can often feel like a warped, counterfactual form of academia. (One popular YouTube exegete, in fact, posts as “The Tarnished Archaeologist.”)

Caracciolo also invokes Umberto Eco’s “influential understanding of the ‘open work’ as an experimental text that is co-constructed by the audience,” which certainly seems apt. But Eco’s examples—the music of Stockhausen and Boulez, the writings of Mallarmé and Joyce—point to a crucial difference. The work of those artists is often forbidding and abstruse, and, for all their influence and longevity, none was ever accused of being a bestseller. Elden Ring and its predecessors are extremely popular, despite their narrative withholding; the experience of playing them is immediate, not esoteric, and people seek them out by the millions. Somehow, the absence of a clear story never makes the game itself feel muddled or meaningless.

This is because video games don’t actually need stories, in any normal sense. No matter what a game does or does not tell you, the primary experience is always your own progress through it—your mistakes, your discoveries, your victories. Everything else, all the plot twists and backstories and characterization a game might contain, is layered on top of that base. Mainstream big-budget games tend to slather it on thick, with plenty of heroism and pathos, but many other games have no explicit narrative at all (Tetris, Bejewled), or one so thin and derivative as to be essentially vestigial: classics like Doom and Mario Bros. have stories that might as well have been written on a napkin.

The Soulsborne games never obscure that fundamental, moment-by-moment experience. It is clear and sharp: an intense, carefully controlled story of exploration, intimidation, and struggle. Every detail of the landscape is made significant, for what it might offer or threaten or allow: paths curling back on themselves, unexpected glimpses of distant areas, items placed just out of reach, enemies lurking in a perfectly inconvenient spot—a precise interweaving of curiosity, anxiety, frustration, exhilaration, and relief.

The architects Luke Caspar Pearson and Sandra Youkhana devote an early chapter of their lovely, astute Videogame Atlas (2022) to Dark Souls, noting the way its landscapes derive from both eighteenth-century Western principles of the picturesque—“the prized scenic views, unconventional pathways and architectural motifs such as ruins [that] communicate a symbolism of deep time and mythology”—and an even older Japanese focus on “the power of ruination.” Much of it is spectacular, but nothing is ever pristine. As you play, you move through crumbling shrines, drowned cities, abandoned palaces, rotting sewers, fields of ash—it couldn’t be clearer, no matter how murky the story gets, that this is a world long since fallen, and from a great height. Its derelict grandeur is also in a certain amount of tension with the constraints on the player, which are many—the game suggests immensity, rather than actually providing it, confining your movements to a limited array of predefined paths between generally small locations.

Elden Ring, on the other hand, is the first of FromSoftware’s games to be centered on a nonlinear open world. Here, the biggest surprises often come from the reverse: how much can be accessed, the surfeit of landscape open to the player. It is enormous compared with the previous games—Dark Souls might take you a few dozen hours to complete, Elden Ring well over a hundred. The shock is not the expanse alone but the density, the way every hillock and cavern is filled with incident and variety. Much of the drama of the player’s progress through the landscape is provided by the periodic revelation of new vistas—a lowland of misty lakes and waterlogged ruins stretching out beneath you as you reach the edge of a cliff; a narrow, unassuming hallway that suddenly opens out above a vast, mazelike royal city—all of which you can, in fact, explore. Perhaps the most celebrated moment in the game involves neither combat nor narrative, but one of these sudden disclosures of space: a seemingly modest stone building tucked away in a forest turns out to be an elevator that descends—lingeringly, unexpectedly, inexplicably—into an underground realm so huge that its distant ceiling sparkles with stars.

In any other medium, Elden Ring’s shadowy, archaeological anti-epic would be alienating and experimental. If told conventionally, its remix of fantasy tropes might seem jumbled. But as a video game, it works—in many ways feeling more cohesive and natural than the rigid, cinematic storytelling so many other games pursue. One of the insights underpinning FromSoftware’s games is a recognition of the opportunity that the medium presents—an opportunity not for narrative simplicity, as it has been seen in the past, but for a new kind of complexity, a centerless, centrifugal form of storytelling, defined by discontinuity and uncertainty and yet, at the same time, propulsion and accessibility.

This dispersed form also means that the games’ most powerful effects come not from explicit statement, or from any turn or climax in the story, but from a slow accretion of mood and symbolism. Action games, especially difficult ones, provide an emotional experience somewhere between aesthetics and exercise. They teach you things about yourself—about the limits and possibilities of your reflexes, dexterity, memory, and pattern recognition; about how you respond to your own failures. The texture of this experience varies from game to game. The relatively long, slow animations of the Soulsborne games, especially the early ones, and the inability to cancel an action once you’ve started it, mean that their fights are punctuated by tiny bursts of regret—you watch helplessly as an attack fails, or an attempt at evasion delivers you to doom. You can feel yourself oscillating between playing the game and observing it, rooting for your own success or bemoaning your incompetence.

This experience lies outside, or perhaps beneath, the other aesthetic aspects of the game—you don’t care how beautiful a castle is, or what it’s called, when you’re trying not to die on the ramparts. But the intense, intimate engagement it involves also heightens everything else. Each flickering detail of the world feels significant because, in this more immediate sense, it is.

That larger significance is remarkably unheroic and fatalistic. It starts with all those ruins, of course. Every structure you encounter is, at best, abandoned, and more often choked with weeds and corpses, or haunted, or actively on fire. Many are not just ruins but ruined memorials—decrepit graveyards, desecrated catacombs, vandalized monuments. The biggest, most threatening enemies you fight are often the most pathetic as well, once-mighty heroes who’ve long since been overtaken by madness and decay, towering monsters now aged, sick, or injured. A few even thank you as they die. (In Shabriri’s Blinding Light, a slim, self-published volume laying out a gnostic reading of Elden Ring, the psychotherapist Matthew Burdo notes that the long process of learning how to defeat especially challenging enemies is, “in a strange way . . . a labor of love and attachment.”) You are always too late, arriving long after the true crisis has passed, at the tail end of a cycle. The civilization you explore has already wound down, its flame just about to go out (quite literally, in Dark Souls). And there’s never much you can do about it: at best, you might, with great effort, prolong the sunset a little, or bring about night a little earlier, but nothing more.

Caracciolo devotes a subchapter of his book to the many online discussions of how playing these games has helped people cope with depression. The games insist upon your smallness, the many things you can’t fix, can’t change, can’t know—and, at the same time, never stop providing opportunities for smaller, personal victories, a combination that can, indeed, be surprisingly comforting. This may be part of the games’ broader appeal: in a time of widespread anxiety and pessimism, a grand vision of how to find meaning in the end of things, how to accept it without accepting your own defeat, might make more sense than another blithe rendition of saving the world.

It also is in tune with the deep structures of video games. The endless cycle of failure and repetition that playing a difficult game entails is not something to be vanquished but simply part of the experience, something to be accepted and enjoyed. So, too, with the extraordinary profusion of death in these games—all those catacombs and mausoleums and, of course, your own repeated deaths. Part of this, again, is formal: death is how your failure is communicated to you, as it is in many games; dying is a form of education, as Miyazaki has said.

But the worlds that his games depict also take death as one of their foundational assumptions. It is not, as it is in so many other works of fantasy, something that can be defeated or transcended—the most grotesque monsters in the Soulsborne games are often the result of attempts to do just this—but an inescapable, ubiquitous fact. It can be lamented, resisted, embraced, but one has to come to terms with it one way or another. Dark Souls is not just an immensely popular action game but also an intricate, interactive memento mori: prepare to die is more than a taunt.

Elden Ring deepens and complicates this preoccupation. Its landscapes are littered with death in just about every form: graves, catacombs, and monuments, of course, along with pyres and funerary jars, half-buried skeletons, piles of corpses, hill-size skulls, torture chambers, temples to bloodletting and rot and immolation, giant mausoleums that walk around on huge stone legs. The plot, once you piece it together, turns out to be largely that of a conflict between different relationships to death, competing understandings of it, in many cases literally between different funeral rites (or an unnerving lack of them). The prevailing Golden Order returns corpses to the roots of the great Erdtree, so they can be reborn; earlier civilizations, largely suppressed, burned their dead in holy flames, or buried them in various elaborate ways; and as the Order has broken down, corpses have begun reemerging, wandering the landscape as “Those Who Live in Death.”

In The Dominion of the Dead, Robert Pogue Harrison’s eloquent consideration of the effects that the dead have on the living, he writes that “humanity is not a species” but “a way of being mortal and relating to the dead. . . . As human beings we are born of the dead.” Elden Ring operates from a similar assumption, pushed a little further: “From death,” as a bit of in-game text puts it (found on an item you can acquire by defeating an ancestral spirit, hidden away underground), “one obtains power.” All the ways of relating to death found in the game’s world are funhouse-mirror reflections of real practices. Hillsides are dotted with crucifixions, but the victims hang from curving arcs, not crosses. One character is a “deathbed companion” who lies with the dying, a practice possibly based on a medieval Japanese ritual. The treasure-filled graves of a civilization of “beastmen” are clearly inspired by the prehistoric Varna Necropolis; the Golden Order’s cycle of death and rebirth draws from Buddhism, even as its iconography looks mostly Catholic; the various cremation sites and funerary jars, meanwhile, use Roman symbolism; there is even scattered evidence of something like Viking-style boat burials.

Death is the basic grammar of pretty much every action game; killing and dying are how they organize your play, a fictional gloss on your success and failure. In some sense, Elden Ring’s treatment of it is just another example of FromSoftware’s particular kind of reflexivity: its incorporation of its games’ formal elements into the fiction of their worlds. The world of Elden Ring is built on death because the game itself is. But the persistent echoes of real-world death, and the insistence not just on death and dying but on its aftermath and cultural responses to it—on the basic question of what to do with the bodies—make it all much more serious and strange. It is a game that seems to have decided that death is simply too important to be relegated to a matter of game design. If you’re going to play with it, you need to think about it too—to look at it, feel it, sit with it, and, perhaps most important, appreciate it.

In Elden Ring’s recent expansion, Shadow of the Erdtree, death is, if anything, even more foundational—sometimes quite literally. The architecture of its final area, a spiraling holy city leading to a monumental “Divine Gate,” is built of corpses, with thousands of petrified, writhing bodies somehow mixed into the stone itself.

Most of FromSoftware’s games have received expansions that generally act as distillations of the themes and challenges of the original game. Their narrative relationships to the original games have varied. Some have functioned as an epilogue or finale, others as backstory to the main plot—a kind of playable flashback—or even a commentary upon it. Shadow of the Erdtree is the latter, an alternate vision of monstrous ambition that complements and complicates Elden Ring. It is set in the “Land of Shadow,” an area of the Lands Between that the god-queen Marika cut off from the rest of the continent and magically concealed, and that has undergone a war of genocidal retribution. It is a zone of repression, a holding pen for the people and places that don’t fit in her kingdom, or that don’t align with her divinity: her past, her enemies, her secrets.

Shadow of the Erdtree’s story is more straightforward than Elden Ring’s, a little more conventionally delivered—we follow in the footsteps of the demigod Miquella, who is frequently mentioned in the original game but never actually seen, as he journeys through the shadowlands, discarding various aspects of himself in an attempt to ascend to godhood—but the land itself is even more convoluted. It is dizzyingly vertical, with mountaintops and elevated cities arranged over rolling plains, which are then cut through by deep valleys and caverns, as if a traditional open-world map had been torn and crumpled up.

And everywhere you look, you find death gone wrong, the dead dishonored and abused. Enormous coffin ships are beached along the shore, the hills are dotted with bodies impaled on spikes, the roads are patrolled by huge “furnace golems,” ambulatory cremation pits stuffed with flaming corpses. A “specimen storehouse” is full of strung-up giants, and deep underground the “impure” dead are left to putrefy. In the very first area you encounter, called the Gravesite Plain, you can find a “suppressing pillar,” which declares that this is “the very center of the Lands Between. All manners of Death wash up here, only to be suppressed.”

All our ways of dealing with death inevitably fade and lose their meaning over time, Harrison writes, and if they are not replaced with new cultural forms, we can “find ourselves surrounded . . . by death without knowing how to die.” That is the crisis this game depicts. If Elden Ring’s world is one riven by competing rhetorics of death, none of them sufficient, Shadow of the Erdtree’s is one in which they have all been abandoned, unreplaced: a world where death is meaningless—and life with it.

Descend deep enough into the putrefying underworld and you can meet St. Trina, an alter ego of Miquella’s. A representation of his kindness and love, which he has discarded, she begs you to kill Miquella, to keep him from becoming a “caged divinity,” imprisoned in immortal godhood. As anyone who has lost a loved one knows, love and death are not opposites. The one illuminates the other—makes it hurt, which is another way of saying it makes it meaningful. You do not expect to be reminded of that by a video game, still less one that lets you wield a hammer the size of your torso and get clawed to death by a giant lobster. But this strange mix of the silly and the absolutely serious is what makes these games—and video games generally, the silliest and strangest of art forms—so powerful.