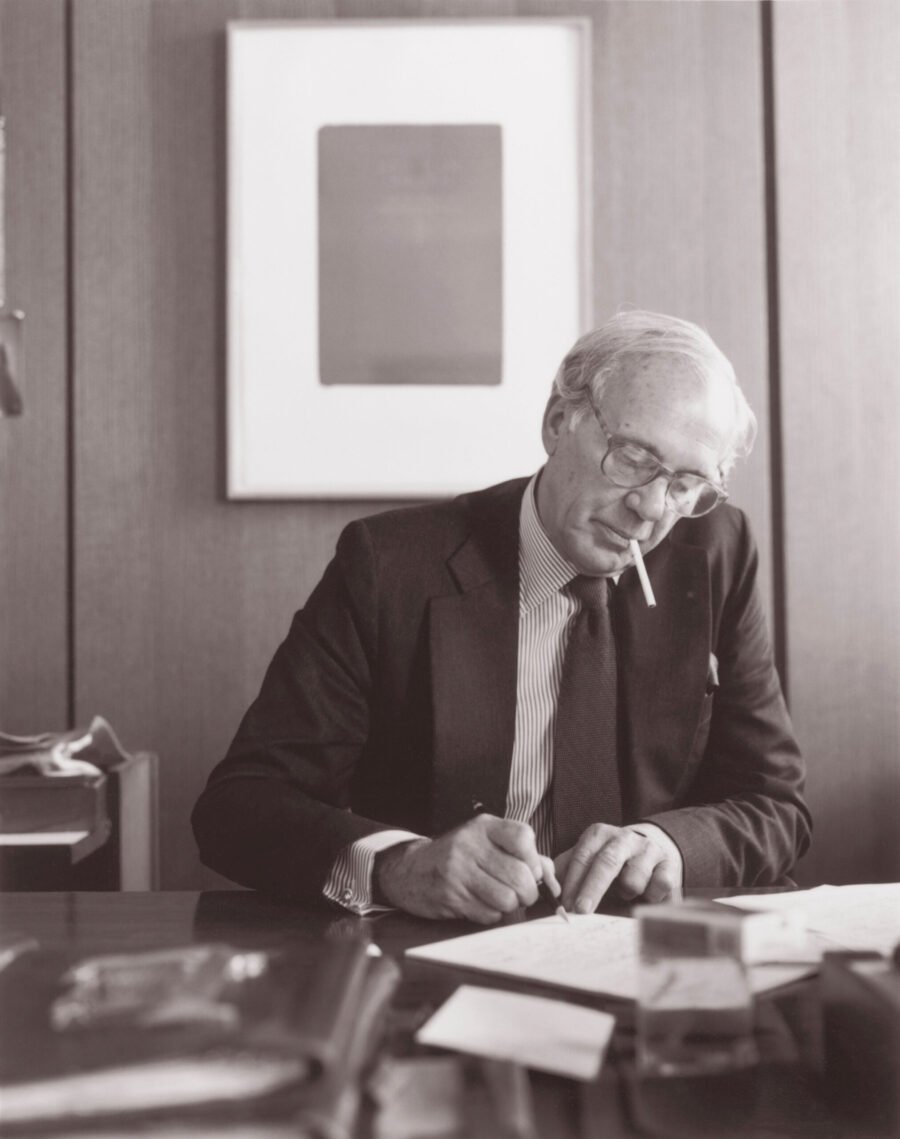

Lewis H. Lapham at work in the offices of Harper’s Magazine. Photograph by Matthew Septimus

Remembering Lewis H. Lapham

This month’s Letters section is devoted to remembrances of Lewis H. Lapham (1935–2024), the editor of Harper’s Magazine from 1976 to 1981 and from 1983 to 2006.

I first worked for Lewis just out of college, having graduated into the Great Recession with a degree in ancient Greek and what could fairly be called limited prospects. On weekends I sometimes took the train in from Long Island, where I was living in my parents’ basement, to fill in for Ann Gollin as Lewis wrote his essays, taking dictation and entering edits into manuscripts, watching, over the course of seemingly endless drafts, what was cut, what rewritten, what moved where, what later restored.

That was an education, but I most looked forward to the drinks that often followed. Part of the pleasure of being in Lewis’s company was the sense that, spending time with him, you’d found the other sane soul in the room. He always had one eyebrow raised in response to the news of the day or book of the moment, and delighted in the puncturing of an overinflated reputation. But what stands out more, in retrospect, is his relentless enthusiasm for the possibilities of writing—a sense of excitement he had kept alive for more than half a century in an industry that had been dying nearly as long as he had worked in it.

He gravitated toward people in whom the lights never went out—usually at least slightly unhinged, like Charles Portis, a friend from his Herald Tribune days, whose short-lived love for Nora Ephron he found so delightfully absurd that, decades later, he would break into a fit of wheezing laughter every time he recounted it. And he often spoke fondly of his mentor, the writer and editor Otto Friedrich, a man who, as he put it in these pages, “wrote books in the way that other people wander off into forests, chasing his intellectual enthusiasms as if they were obscure butterflies or rare mushrooms.” What he found so moving about Friedrich was in large part what made Lewis himself such good company. He was “a humanist in the old, Renaissance usage of the word,” someone who believed that “among all the world’s wonders, none is more wonderful than man.”

— Christopher Carroll

I met Lewis on the thirty-second floor of the Pan Am Building. I was a wealthy business mogul’s secretary. Lewis worked in a tiny office adjacent to the central room. It had hospital-green walls and no windows. There, on a metal fold-up typing table, he wrote a syndicated newspaper column. One June afternoon there was a birthday party in the mogul’s office. A man I’d never talked to said to me: “Have you noticed that all the pictures on the walls are of dogs and horses? It’s like a child’s room.” I’d seen those pictures many times a day for more than a year but had never looked at them or thought of them in that way. I laughed. He was right.

Months later, when he told me he was leaving to return to his post as the editor of Harper’s Magazine, Lewis became uncharacteristically shy. After a few awkward minutes, he asked me if I would consider being his assistant. “I think your title would be executive assistant,” he said, trying to make the offer appealing. “You’ll meet writers. You’ll talk with authors and literary agents.” I’d read Harper’s when I was in college. It was the best magazine in the country. We both were quiet. I said yes.

That was forty-one years ago. I think now of Lewis’s favorite Auden poem, “Many Happy Returns.” Auden gives birthday advice to a very young boy: “Travel for enjoyment, / Follow your own nose.” I think now of a question Lewis asked a writer when they were deciding what piece she should write next: “Where do you want to go?” Lewis seldom gave advice, but if he did it was along the lines of Auden.

— Ann K. Gollin

Lewis Lapham was an elegant man, a prince in the autonomous Republic of Letters. He was wholly confident in his understanding of quality and substance, and ready to bring a lordly insouciance to bear in their defense. And he was bold and gracious. Perhaps our literature and journalism can still sustain figures of this kind, proudly rigorous in adhering to the standards the practice of letters claims for itself. If nature has its noblemen, culture does, too, and Lewis Lapham was living proof.

— Marilynne Robinson

Lewis Lapham is dead. An oak has fallen. The Henry Jamesian “real thing,” with his beauty and baggage. (Like James, he lamented the moral vacuity of the Wasp pseudo-aristocracy in part as a way to remind you of its power.) And yet, he was a Grub Street man to his fingernails, a man perpetually slumming. I had somehow got it into my head that he’d decided to skip death. Maybe it was the magnificent rebuke his career offered to Fitzgerald’s line about “no second acts in American lives.” Lewis lived to inspire a generation of readers who knew him only by his second act, his reinvention, in Lapham’s Quarterly, of the historical almanac. I’ve met fans of his who don’t even know about his Harper’s days.

If you ever worked under him at Harper’s, you get how unlikely that seems. You may not have understood much about the magazine, but you knew that its fate was painfully knotted up with the tall man in the suit and tie, smoking Parliaments and underlining Montesquieu quotations in his office. Surely the two, the institution and the man, would go down together. Turns out they survived each other.

He published my essay “Horseman, Pass By” more than twenty years ago. No other piece was more important in my life, from a career aspect, or maybe even from a writing aspect—who knows. I was a kid when I knew him. I learned something every time he opened his mouth. He died in Italy—the wayward scion of San Francisco in the Old World, where his soul was most at ease.

I remember a time in the offices on Broadway, late one night in 2002, when the most enormous amber moon rose over the city. There were only three or four other people around at that hour. We instinctively shuffled into Lewis’s office to look at the spectacle with him. He stood at the window with his hands in his pants pockets. His dark-rimmed glasses and elegant slouch. Nobody said a word.

I wish I had kept in better touch but did get to tell him, the last time we spoke, that I knew how lucky I was to have been around him, at a formative stage. He didn’t aw-shucks me. He knew I was serious.

I’m thinking about his family and the people who really loved him or were loved by him. Goodbye, Lewis.

— John Jeremiah Sullivan

He spoke with his cigarette in his mouth, so he said everything behind a cloud of smoke like Moses at Sinai.

— Annie Dillard

How clearly I can still see Lewis stalking the halls of this magazine with a Parliament between his fingers, ashes flecking the sleeves of his coat, appearing at my office door to read aloud the lede of his latest essay or to hand me a manuscript that had excited him. I worked with Lewis for more than ten years, and during that time our editing proceeded from a strict rule of intellectual humility. Our readers, Lewis always used to say, are smarter than we are. Our task was to deliver the magazine they deserved. Editors and writers who assumed that readers were ignorant or lazy or stupid succeeded only in producing material that conformed to those expectations.

Lewis believed as a matter of principle that intelligent readers demanded vigorous, beautiful writing that conveyed clear thinking and honest reporting. That’s what he demanded, and that’s what he delivered, month after month. He pursued the subjects that he found interesting and important, and he trusted his audience to come along for the ride. Lewis extended that principle to his staff. He told me many times that he always tried to hire people who were more intelligent than he was. I’m not sure he always succeeded on that score, because Lewis was a very clever man, but as a rule his method and his example can’t be beat: hire the most talented people you can find; publish the best writing you can conjure up; trust your readers.

— Roger D. Hodge

Lewis taught me everything I learned about magazine editing. I remember the many times he held court at the Noho Star, and when other editors arrived told the bartender to “bring some water for my horses.” Also the many times I sat or stood next to him and delighted in his conversation and his wonderful laugh. He was enormously generous in his teaching and extremely affectionate in his nature. I will miss him dearly.

— Ellen Rosenbush

I first met Lewis on the page, when I started reading Harper’s in college. I had picked up a copy of the January 1997 issue because I was intrigued by the cover. It confidently announced itself, with the simplicity of that black type against a white background, the only color coming from a horizontal slab of a photograph and a delicate ribbon of text at the top. I opened it up and was immediately hooked. The Index and the Readings section, the long articles that blended sharp reporting with the idiosyncratic voices of the people doing the reporting—I had never encountered anything else like it.

I spent most of my impressionable twenties working at Harper’s, and I learned that the man himself turned out to be like the magazine he edited: extremely serious yet darkly funny, coolly knowing yet insistently curious. A familiar sound in the office was Lewis pacing the halls as he worked on his Notebook each month. Despite everything he had accomplished, he was always candid about the fact that writing, when you cared about it, was hard.

In all the years that I knew Lewis, I can’t say that we talked about anything truly personal—he just wasn’t like that, at least with me. We talked mostly about ideas, about sentences, about essays, about books. In that way, even if he didn’t offer up revelations about his life, he nevertheless changed mine.

— Jennifer Szalai

When I was art director of Harper’s Magazine, I saw Lewis Lapham not only as the magazine’s editor, but also as my own literature professor. The first book he introduced me to was Balzac’s Lost Illusions. After that, there was Père Goriot and Cousin Bette, Zola’s Thérèse Raquin and La Bête Humaine, Stendhal’s The Red and the Black. They all had to be Penguin Classics. No other version would do. We would talk about each one at length.

I don’t think I was a special pupil in this regard. He showered his knowledge on anyone who admired him. Over time, after I married a writer, books became more important in my life. I passed along Lewis’s suggestions to my husband, Tom Wolfe. He, too, became enraptured with their style and status details. The books Lewis had suggested greatly influenced his writing, so much so that one of his best friends referred to Tom as “Balzola.”

The last time I saw Lewis, I asked him what he would suggest I read. Empire by Gore Vidal, he replied. I just ordered it.

— Sheila Wolfe

I learned from Lewis—learned especially the delicate etiquette of interacting with the kind of writers he wanted (and I wanted) to publish, writers who took seriously their ideas and words, their sentences and structures. Being in an office next to his at Harper’s, being in meetings with him, being around him, I learned how to compose a tactful but firm rejection letter; how, over the phone, to encourage a rewrite, and then, weeks later, still another; how to diplomatically reject a writer’s idea for a piece offered over lunch and provisionally suggest something similar, or perhaps not similar at all. My understanding of how difficult ambitious writing could be deepened: I came to care more, or care more carefully, about writers and their manuscripts. And my own ambition to spend a life editing magazine writing deepened, too.

— Gerald Marzorati

Lewis Lapham taught us the difference between the humdrum magazine article—a species of day-after disposable journalism—and the essay as a force of wit, judgment, satire, discovery, laughter, lastingness, art. Whatever the subject, he made of it an idea as shapely and meaningful and urgent as Necessity itself. He has been, and always will be, our Hazlitt.

— Cynthia Ozick

Comparisons to Mencken and Montaigne are apt enough for Lewis Lapham’s writing, but to speak of his care for other writers the best precedent may be Samuel Johnson. Like “the Great Cham of literature,” Lewis never sat so high as to lose touch with Grub Street. The full tally of its denizens that he helped I can’t claim to know; I can only say that he helped me and that my debt is all the greater for my lesser place on the list. After I wrote my first piece for Harper’s, he asked my editor, Ellen Rosenbush, “Where did you find him?” No one could have faulted her metaphors had she said, “Scratching at our basement door, all ribs and missing an ear.”

He gave me a home—two homes after he’d founded Lapham’s Quarterly. As soon as I learned of his death, Johnson again came to mind, in a line he’d written on the passing of a generous host: “the face that for fifteen years had never been turned upon me but with respect and benignity.” You want such a face in your head and at the head of the table. For some of us, that’s where Lewis will always sit.

— Garret Keizer

In 2000, I received a call from Lewis Lapham, the storied editor of the venerable Harper’s Magazine, requesting an in-person interview during my Green Party presidential campaign. Accustomed to reporters clinging to the single question about “being a spoiler” and my usual rebuttals (“focus on the spoiled political system”), I was pleased by Lapham’s interest in our broad and deep agenda, our modes of campaigning, and the historical context of third parties breaking important new ground. He returned to New York and wrote a cover story on our campaign at the time of a near blackout of our candidacy by the mainstream media.

Seeing him as a national treasure, I offered to secure one thousand subscriptions to Harper’s if he would stop smoking his several packs a day for two years. NBC’s Today show got wind of this exchange and put us both on the air. I made my case but, though his usual courteous self, he wouldn’t budge.

In the succeeding years, we would exchange telephone calls to assess the outrages of the day. Lapham was not content with opening minds to “beautiful and strange” imaginations for the world: he waded into controversies.

— Ralph Nader

Lewis will long be remembered for his piercing critiques of political hypocrisy. But there were two more private sides to him, which I saw closely over my twelve years at Harper’s, six of them as the magazine’s deputy editor. The first was that he was a shrewd judge not only of writerly talent but of editorial chops. He assembled a remarkable team of editors, usually quite young, who grooved on playing with language and ideas. Working for Lewis, we felt empowered to juggle the live ammo of words. He required ideas, arguments, and narratives, and we labored faithfully to provide them. Nearly all his editors went on to populate the wider world of publishing, deploying the priceless skills Lewis had taught them.

The other aspect of Lewis that readers didn’t see was how he struggled to write his column every month. I would go into his office as he marked up his manuscript and took a drag on his Parliament cigarette every minute or so, often preceded by a catarrhal clearing of the throat. When the column was going well, he would soon strut a bit in his suit and tie and cuff links as he exited his office, and when it was not—and that was often—he remained sunk down at his desk in his discouraged funk and cigarette smoke. He was an impossibly elegant man, but in these moments he was just another writer, confronting the vastness of the blank—or, more likely, deeply improvable—page, under the pressure of a deadline. That he dependably emerged from this struggle with a ferocious essay was ever inspiring to his band of editors and of course a keenly anticipated provocation to his loyal Harper’s readers.

— Colin Harrison

For years I was wary of Lewis—always so impeccably dressed, so easy to spot in a crowd—because I thought that he was one of those hyper-entitled, older white guys who might say something sexist and insulting. It took considerable persuasion for him to sign off on “Scent of a Woman’s Ink,” my Harper’s essay about the literary world’s discrimination against women. But after the story blew up (this was shocking news in 1998), Lewis was fully on board. He always encouraged me to go further, think bigger. Yes, the far right wanted to destroy U.S. public education. Yes, reality TV was a hotbed of proto-MAGA ideology.

Eventually we became friends. I saw past the patrician to the generous, smart, funny person who loved books and ideas, who could quote—aptly and at length—from Epicurus and Montaigne. Occasionally, we’d have lunch at an Italian restaurant he liked in Gramercy. It was quiet, and easy for him to go outside and smoke. Sometimes he called to invite me to write something for Lapham’s Quarterly and, once, to guest-edit an issue.

Already I miss him terribly. I miss his presence in the world. I miss those lunches in Gramercy. I miss his particular mix of pragmatism and idealism. I miss what he represented: a way of life, a vivid interest in language, history, narrative, art, argument, and thought. I feel as if something huge has been lost, something larger even than Lewis.

— Francine Prose

The story of my writing life has two parts: before and after Lewis Lapham. In the before, I was a writer of fictions in the American postmodern style. My “coach” was the late John Barth. The “after” began when Lewis and Roger Hodge accepted my essay “The Middle Mind” for Harper’s Magazine, which was soon followed by a book of the same name and six more works of social criticism, one of which, The Science Delusion, I dedicated to Lewis.

Having worked with independent literary publishers like Fiction Collective Two and Dalkey Archive Press, I was acutely conscious of Lapham’s Quarterly’s need for a working endowment. So, Lewis and I were in Las Vegas with the late Barbara Ehrenreich at the invitation of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. One night, we strolled around the Bellagio casino, under Dale Chihuly’s colorful blown-glass ceiling. I bought ten one-dollar tokens for the slot machines and handed them to Lewis, saying, “Maybe Vegas can do some fundraising.” It was fun to see him pulling the handle, but we didn’t make any progress on the endowment.

I’m seventy-three years old as I write this, less than a week after Lewis’s passing. Like Barth and Ehrenreich (and Willie Mays), he, too, is now one of the “late.” In my mind, I still live in the world they helped to create, but that world, too, seems now more late than not. But that just gives Harper’s editors, writers, and readers something to work on going forward.

— Curtis White

I started working at Harper’s several months after Lewis left to found Lapham’s Quarterly, but his imprimatur was everywhere. As the new assistant to Roger Hodge, I loved hearing Lewis’s gravelly voice when I answered the phone. As a new smoker, I loved seeing Lewis standing outside this or that event, puffing a Parliament in his elegant, unrepentant way. Cadging a cigarette was the perfect pretext for a nervous fangirl to venture a how-are-you, and to prattle; yet Lewis was unfailingly gracious, and generous to young people. Some years later, we struck up a phone friendship, and sometimes met for lunch at Il Cantinori or a drink at Paul & Jimmy’s. “A Letter from Lewis Lapham” was the subject line of all his emails. “I have more faith in wooden rulers than I do in plastic wrapped computers,” he wrote to me at one point. I will miss hearing his takes on the present day’s derangements and how they are informed by the wrinkles of the past. The arc of Lewis’s intellect and imagination was long. It feels fitting that I am composing this by hand in the countryside, where a storm has blown out the Wi-Fi.

— Gemma Sieff

Lewis and I became friends in the Nineties after his daughter worked as an intern in my newspaper office. The great editor and essayist and I shared some similar interests, particularly in history, as well as a distrust of conventional wisdom and an appreciation of the absurd.

I can still hear Lewis’s smoky baritone, with a patrician tone that reminded me not of San Francisco, where he was raised before he was sent off to a Connecticut boarding school, but of the old East Coast Wasp upper crust. Lewis could be briefly irascible, but his kindness almost always triumphed. He spared little effort to help writers and editors develop their talents as far as they could take them. His mentoring of young staffers at Harper’s and Lapham’s Quarterly was legendary, rich with patience and idiosyncratic ingenuity, as he guided them through the briar-filled woods of publishing. He was always quietly doing favors for others—for example, making himself available to talk with young people whom I and other friends sent to him for employment advice. I was touched when he scurried to try to find me a new job when the company I was working for was sold. (I kept my job.)

That reminds me of his oft-expressed gratitude for those famed journalists who had helped him become a great magazine editor, such as Otto Friedrich and Jack Fischer. Lewis was a very gracious man. And such fun!

— Robert Whitcomb

You might be forgiven for thinking Lewis Lapham was something of an aristocrat, given his prose style, his family background out of some West Coast oil barony, or his posture when he smoked one of his Parliaments. He not only seemed stately, but gave you the impression he started being stately around age five. But what’s always stuck in my mind ever since he hired me, which happened after a half hour of laughing and screaming about story ideas, are his words when he sent me out his office door. “Jump in,” he said. “Get in the game.” He meant it.

At the time, Magazineland was a patchwork of warlords. The New Yorker and the Times Magazine, GQ, Vogue, Esquire—all were run by aloof tyrants, typically described as legendary, who made every call before a small audience of tremulous editors. But Lewis was more often a small-d democrat than not. He could be persuaded into publishing something he’d rejected or into killing one of his darlings. As an editor, he loved to challenge acceptable opinion or bash received wisdom—and liked it when you did the same to him. Although I might have bumped up against a boundary when, out for a scotch at Temple Bar after a close, the subject of his latest column came up and I somehow blurted, “What, no court jesters this month?” He laughed, but his warm nicotine crackle was more of a talk-show ha!

Lewis Lapham was sort of the Dylan Thomas of journalists. I mean, Thomas was a great poet who, after reading him, you realized was like no other poet—not really part of any genre, or movement, or generation. Lewis Lapham was a journalist, but not like any journalist I’ve ever known. He wrote in a genre that he invented. He was part of a movement unto himself, and, in so many other things, was a bit of a mystery to those around him.

— Jack Hitt

Lewis Lapham. Staunch. Old money. A Yalie. Always insouciant. He left his heart in San Francisco, summered in Newport, but died in Rome. A child of winter, he was a bit of a throwback, as most children of winter are. He was so adoring of me. I will forever think the world of him. We went out for “Mobutus” on Lafayette. He always told me, “You are headed up, up, up, kid.” He wore lavish, well-tailored suits for many days in a row. For him, I smoked Parliaments and talked John Daly.

I loved Lewis. Really loved him. Most editors want to replicate their minds, but their minds are simply not that interesting. Lewis was a cannonball of history. He didn’t just have style—he was style. He knew sometimes you show up in India and the Beatles happen to break up. So few people are worth the feeling of admiration, but he was.

The Harper’s internship paid no money. I never said anything, but it was a hardship to do it even though my college gave me credits. Right before we left, Lewis sold some Muhammad Ali memorabilia he had and gave four fat checks to our internship group. I needed that money so badly; I’ve never gotten over the feeling that he knew that. But as ever, Lewis never let people feel apprehension about their right to exist in the world. He never treated people coarsely; he just treated everyone equally. Everyone was a discovery, a new conversation to have, another person to listen to and smoke with. Lewis was aloof but warm. No one but he and my mother have given me such a deep, unshakable understanding of class: a fading sensibility but one that he had in droves. Thank you, LHL.

Love,

— Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah

One afternoon that first year of the pandemic, at two o’clock, I walked past a flower shop and a pharmacy to the deli on Third Avenue. Lewis, who even in his late eighties never shook the habit of working from the office, had asked me to grab him lunch. I remember the man behind the counter always lifted his mask as he said, “The usual?”

“Yeah, the usual.”

Liverwurst with butter and mayonnaise on rye, and a chocolate milkshake. That evening at six o’clock, like every evening at six o’clock, we decamped to a restaurant on East 18th Street, where Lewis asked for a Bloody Mary, in a wine glass, and I asked him to tell me stories about the past. (Months earlier, he’d told me about playing Beethoven in Thelonious Monk’s apartment, then offered me a job.) After work, I always liked to ask about the past, because often when I asked about the present, he’d say something like, “You know, I’m still struggling.” Lewis was not yet speaking about his health so much as whatever it was he was writing—a letter to an old friend, another essay. Every word was dashed off longhand, scrawled in the blue ink of his Montblanc, then dictated into a digital tape recorder, which was transcribed and printed and edited, over and over and over again, until one night, he might smile and say, “Goddamnit, it’s done.”

— Adam Iscoe

Last year, Lewis wrote what was, to my knowledge, his final essay, the Preamble for the Energy issue of Lapham’s Quarterly. I was, somehow, his editor, and I could see him at work all summer inside his glass-walled office overlooking Union Square. On one such day in June, as forest fires raged in Quebec, the smoke outside darkened the Manhattan sky, which turned orange in the afternoon; the building smelled of campfire. Lewis kept writing at his desk, as he always did. On his way out that evening, he offered me a drink—“in consolation,” Lewis said, because his essay was late.

In the fall, I visited Lewis several times on the Upper East Side, picking up the day’s newspaper and a coffee on the way. He was rereading Moby-Dick, a novel he had loved since childhood. Lewis appeared to me oddly youthful, as though the reading itself had turned the clock back by half a century. “I have swam through libraries and sailed through oceans,” Melville wrote, and so had Lewis. I thought he might live forever. Perhaps the rules had been suspended and invincibility attained.

Lewis had been a hero of mine since I was a teenager in North Carolina, and I remember the first time I met him, many years later, for a job interview at Tarallucci e Vino, around the corner from the Quarterly’s office. We discussed, among other things, his view of time and space, which Lewis summed up in a simple way: “It’s all one place.” That is: all the world’s history, as disparate as it may seem, exists together, in “one place,” one conversation among voices in time—or at least the Quarterly made it so. I believe that it was this grand sense of the immediacy of the past and the freedom of imagination it allowed that motivated Lewis to keep reading, writing, editing—to keep making magazines—for as long as he could.

— Will Augerot

Only at the end of his life did Lewis and I speak on the phone. Before that, beginning in 1978 and throughout our work together and later friendship (I met him as a student at Columbia, and he hired me to work at Harper’s as an assistant editor), we talked in offices, over drinks, at lunch or dinner, after golf, and in emails and letters (I wrote; he answered succinctly). But until he moved to Rome for what turned out to be the last round of his life, we had never spoken much on the phone, except to arrange meetings.

Once we got the hang of these calls, we talked about everything—his books in storage in Brooklyn, moving his beloved office desk to Italy, the novels of Alan Furst and the histories of Philip Guedalla, whether he would die abroad, Tucker Carlson’s interview with Vladimir Putin, my recent trips to Mexico and Cuba in search of imperial battlefields, his own visit to the Bay of Pigs for his 1989 television series, America’s Century, and, endlessly, whether he had the stamina to write one more essay for Harper’s—on democracy.

In his Roman twilight, Lewis could not move about easily. He didn’t have his desk, nor could he write in longhand with a fountain pen while propped up in his bed, but he never lost his abiding curiosity about the world or his determination. In brooding about democracy, he reread the Aubrey–Maturin novels of Patrick O’Brian, plus Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Upton Sinclair’s Lanny Budd series. Lewis just didn’t know how he would start the piece until he came upon this quotation from Justice Louis D. Brandeis (in effect, his final words to me): “We must make our choice. We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we cannot have both.”

— Matthew Stevenson

In 2017, I met a man in Washington Square Park who was homeless but in possession of a handsome desk set. He had it on dollies, he explained, so the park police couldn’t harass him for setting up furniture. The desk’s only contents were, in one drawer, a handle of vodka, and, in another, a copy of Lewis’s Pretensions to Empire. Both were indispensable, he said. I told Lewis, who was delighted at my new friend’s fine taste and wanted to meet him. We never found him.

— Rafil Kroll-Zaidi