“Sun City: Couch Potato,” by Kendrick Brinson, from her series Sun City: Life After Life © The artist

New Books

The AARP stands for nothing. In 1999, the group announced that its four-letter initialism, which for more than forty years had denoted the American Association of Retired Persons, would thenceforth have no defined meaning. What once was a name became a vacuum. According to the AARP’s website, this cavity “reflects the full diversity of our membership,” a significant percentage of which is not retired. It also reflects the organization’s impossible desire to distance itself from itself. The first boomers were heading over the hill in ’99, and for them, one newspaper columnist wrote, “AARP might as well mean RIP.” The name change catered to their denialism. No old people here—only older people, approaching oldness asymptotically. You may not realize you’re looking at an older person until there’s a younger person beside him. And both of them might belong to the AARP, which welcomes everyone eighteen and over. It’s an interest group that has achieved a state of ascetic disinterest.

Still, the AARP has flourished while other old-age advocacy groups have withered on the vine. Nary a mailbox in this country has not bulged with its onslaught of membership cards, brochures, insurance policy notices, and, above all, with AARP The Magazine, whose readership is roughly sixty-five times that of this magazine. For decades we’ve been living in AARP Nation, as James Chappel calls it in Golden Years: How Americans Invented and Reinvented Old Age (Basic Books, $32).

This is a place where a fifty-year-old and a ninety-year-old are both expected to be vital and optimistic, in search of an elusive dignity that derives from access to good weather, reasonable prices, and pharmaceutical interventions for erectile dysfunction. Here, older Americans clamor not for better public health care or a universal basic income but for “private-sector solutions to the problems of senior living,” Chappel writes. Chief among those problems has been the perception of seniority itself. The AARP emphasizes lifestyle over public policy. Its message, as Chappel hears it, is: “Anything young people can do, you can do too—ideally, by using AARP services!”

The heart of AARP Nation is, of course, Florida. Burnished by the senior citizens of yesteryear into a gleaming mecca of early-bird dinners and palm-fringed shuffleboard courts, it is today a hub for pickleball and Hard Mountain Dew “Definitely Over 21” launch parties. A 1972 article published by the AARP opined that, had Ponce de León remained in Florida, he would’ve abandoned his quest for the fountain of youth, “preferring retirement in its sunny clime to eternal youth elsewhere.”

The conversation around aging used to be more heterodox and more demanding. To juice the economy during the Depression, a doctor named Francis Townsend proposed a payment of two hundred bucks a month (roughly $5,000 in 2024 dollars) to every American over sixty on the condition that they spend all of it within thirty days. The Townsend Plan launched a thorny debate over the purpose of old age in an industrial society. His slogan was “Youth for Work, Age for Leisure.” Across the country, some two million people joined Townsend clubs, agitating for the passage of the plan in Congress; the press followed around a sexagenarian man and wife as they proved that parting with two hundred dollars was easy.

Had he lived to see the first great retirement communities in the Sixties, Townsend might have smiled to learn that one of them was called Leisure World. Behind its rotating thirty-foot globe, retirees rode oversize tricycles and took up woodworking or the kazoo. (“Leisure World seems to have been a genuinely fun and inviting place to live,” Chappel writes, his shock wafting from the page.) But only the rich could afford to live there. Townsendites had found some succor in the Social Security Act, but most felt that it didn’t go nearly far enough. This is not a view we’ve heard lately. In Chappel’s telling, Social Security and Medicare are the bedrock of the American concept of old age, and yet few old-age advocacy groups do much to acknowledge or bolster them. Even The Golden Girls—a liberal sitcom, especially by the standards of the Reagan years—hardly mentioned the programs in its many episodes on financial precarity. Make no mistake: the girls were getting a little help from Uncle Sam.

Summer Sisters, by Jessica Brilli © The artist. Courtesy Maddox Gallery

The elderly no longer know how to refer to themselves. “Older Americans” may summon a wide horizon and a plump sunset, but it’s terminally inclusive. “For decades,” Chappel writes, “the central idea had been that ‘the aged’ or ‘senior citizens’ were a distinct identity group with distinct needs, and that those needs should be met by the state.” Today, no one can meet the needs of older people, because no one knows who they are. The closest thing we have to Townsend clubs now are boomers in Mustangs blasting Pete Townshend, hoping they die before they get old, not accepting that this means they would already be dead. It’s easy to resent them for this, especially as they continue to hoard their wealth. You look for the tan lines they get from keeping their heads in the sand. But I feel for them. Should I get the chance to age, I have no confidence I’ll do it gracefully.

Chappel delves into statistics and academic conferences more than he does the psychology of old age, which he can’t quite bring to life. He’s what you’d call a big-picture guy, writing about a subject whose pathos is all in the close-ups. Even so, there’s a profound loneliness skulking around his book. “This story is not a tragedy,” he writes—and yet it always ends in death. His more leaden sections finally land on grim reality, as in this one about a study of nursing homes from the early Seventies:

A full 39 percent of the time, residents were doing nothing at all, what the investigators called “null activity,” and which included sleeping, sitting alone, or staring into space. Another 17 percent of the time was classified as “passive activity” . . . as when smoking or rocking in a chair. “Thus,” they concluded, “56 % of the residents’ time during the day, from morning to evening, was spent doing nothing.” Much of the rest was spent watching television.

I’ve just understood why the AARP hollowed out its name.

“Null activity” is fiction’s raison, the seething, ruminant life of the mind. You might call it “staring into space.” I call it The Loser, by Thomas Bernhard. I wouldn’t have pegged Tove Jansson—a Finnish writer best known for children’s books about a race of rotund, huggable trolls called Moomins—as a master of null activity, but she was. Visiting Florida in 1972, Jansson was amused and alarmed by St. Petersburg, a city dominated by sunny silence. “The peace was almost sinister,” she wrote. “Everything has been prepared for rest and old age, inexorable and ideal.” The stereotypes of retirement had not yet ossified: AARP Nation was a new territory, undiscovered if not fertile, and Jansson explored it in Sun City (New York Review Books, $16.95), now reissued in Thomas Teal’s 1976 translation. The novel ensconces us on the veranda of St. Petersburg’s Berkeley Arms, a well-kept retirement home where the days pass in breezy, saturnine, sometimes bracing idleness. Here there’s time enough to get some thinking done about rocking chairs, how “it took a certain amount of attention to keep a rocking chair from rocking” and what a feat it would be

to place rocking chairs in groups, that is, rocking toward each other. It would take a great deal of space, and in the long run it might be tiresome. Of course the original, the natural idea was a single rocking chair in motion in an otherwise static room.

There’s not much to do in Sun City. A novel about null activity doesn’t go in for plot. Jansson just gathers her oldsters and makes a spectacle of their segregation. “What a clever idea to get us all together in the same place where we can enjoy ourselves without being in the way!” says one character, sincerely. They grouse and gripe their way toward the Spring Ball, with its Cavalcade of Hats, at which the mayor dies mid-dance. A closeted old vaudeville star, the exquisitely named Tim Tellerton, comes to town, both to outrun and relive his glory days. There’s the sudden appearance of an irascible ex-wife; a trip through Silver Springs State Park on a glass-bottomed boat and a misadventure in the forest; the deaths of the Pihalga sisters, who were so quiet that no one knew their first names. And cigarettes by the carton—this is back when seniors still lit up.

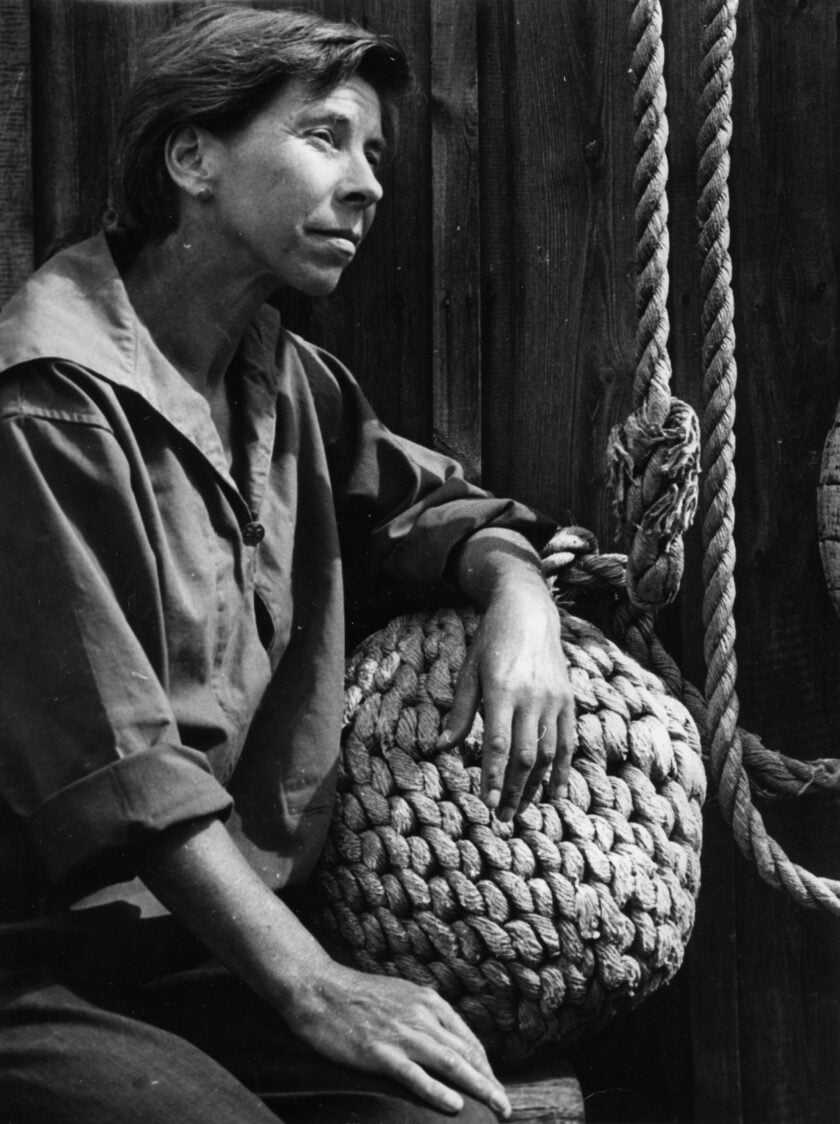

A photograph of Tove Jansson in Pellinki, Finland, 1956 © Per Olov Jansson

It can be hard to tell Jansson’s characters apart. They all mourn and nurse their private grievances. The blur may be intentional: the sun seems to dry the distinctions out of them, and they know it. The women outnumber the men, who have, of course, died, leaving a fraught mass of Hannah Higginses, Elizabeth Morrises, Evelyn Peabodys, Catherine Freys. Their bickering is amusing, particularly with Jansson’s arch timing, but it’s when they’re quiet that the novel soars. Frey, wandering the hot streets on a quest to get her hair done, sees old ladies by the hundreds in salon chairs: “So much old hair being washed and set, dyed, sprayed, and back-combed, so much white and gray down being brushed up across balding heads!” Soon she is one of them, sunken

under plastic shrouds deep into a world of damp terrycloth and the humming greenhouse warmth of dryers, a world promising forgetfulness for several peaceful hours. Everything in the crowded room was pink, even the telephone. It was a closed, feminine sanctuary where Miss Frey fell asleep, massaged at last with Silver Spray Number Five.

The Berkeley Arms overlooks a placid harbor, the home of a replica of the HMS Bounty, a tourist attraction on which wax models of sailors reenact their famous mutiny. Visitors receive plastic hibiscus blooms. The mutineers have been tamed. Whatever gave rise to their unrest is just a memory. There are only two young people in this novel, swept up in a passionate, naïve romance. One of them is convinced that Jesus will return any day now—to the beach, probably, in Miami. “If they only knew!” he thinks about the old. “If they only realized that time had run out and their whole ruined world didn’t matter any more.” Someone could’ve gotten this message to Joe Biden before the primaries and saved us all a lot of grief.

I thought of Biden a lot while reading Sun City, and also of Dick Van Dyke, who, now ninety-eight, has been old (still handsome, though) for the entire time I’ve been alive, and who has taken to introducing himself at public appearances by saying, “I’m what’s left of Dick Van Dyke.” This book’s original dust jacket called it “an indictment of the American way of old age,” which is too strong an assertion for such a wistful tale, though it has notes of well-deserved condescension. Probably only a Scandinavian could have written it. Jansson knew she’d be retiring to the ample bosom of the Finnish welfare state, not hacking it out with clipped coupons and wraparound sunglasses. The St. Petersburg press was not kind to her. One critic complained that Sun City would have you think that the city’s whole population was elderly, when in fact only 27.3 percent were sixty-five or older. Another critic faulted her for having “carelessly misnamed” “the familiar Senior Citizens Club near The Pier” as the “Senior Club.” The critic made no comment about the sign that Jansson hung in her Senior Club: members dance at their own risk. Was that really there? I believe it was.

“I am very old indeed and cannot understand why the younger generation, instead of knocking at the door, should bash the fuck out of it,” Noël Coward wrote in a 1957 diary. Apparently this expression of senescent contempt is the earliest documented usage of the construction to _ the fuck out of, meaning to do something “to an excessive, violent, unpleasant, or powerful extent.” The citation is one of thousands in The F-Word (Oxford University Press, $22.99), a dictionary dedicated to the word fuck “and every compound word or phrase of which fuck is a part,” now published in a rousing fourth edition edited by Jesse Sheidlower, an expletive expert. He’s expanded the book by more than 150 pages since its previous edition, from 2009: a tribute to the idiomatic ingenuity of the social-media age, or just the pissiness in the air. Fuck “just feels good to say,” Sheidlower writes in the introduction—emphasis his. I worry about the home life of someone so steeped in profanity. Does he start every fucking day brewing a piping fucking hot cup of fucking coffee? Or does he, like Proust, sleep in a cork-lined room to keep the noise out?

Pink Telephone, by Aglaé Bassens. Courtesy the artist and HESSE FLATOW, New York City

Fuck, commonly assumed to be an Anglo-Saxon oath, is of Germanic origin; not until the age of Middle English do we begin to meet men with names like Ric Wyndfuk (of Sherwood Forest) and Roger Fuckebythenavele, who may have tried to fuck someone by the navel. The word was rarely put in ink for centuries, so heavy was its curse. Its first appearance in American print resulted from an 1846 Missouri court case in which a man stood accused of copulating with a horse. “Special Instructions to Players,” a memo circulated among major-league ballplayers in the 1890s, reproduced phrases such as “A dog must have fucked your mother when she made you!” but only to prohibit them.

By then, fuck was well off to the races, proliferating in inventive, apoplectic, demotic ways. It’s a beautiful thing to watch it ripple through the language, expressing what had been inexpressible. New to this edition are brainfuck, fuckton, fuck around and find out, and thank fuck. Sometimes the pleasure is in seeing how early a fuck variant was used: “even minor antedatings represent a meaningful advancement of our knowledge,” Sheidlower writes. Fuckstick, formerly belonging to 1973, has now been traced to 1904, when Aleister Crowley used it in “The Futile Fuck-stick; or, The Distiller’s Dilemma.” Over five hundred fucking pages, the only omission I noticed is a sterling coinage from William Friedkin’s 1995 movie Jade, in which David Caruso, sniffing around where he doesn’t belong, nudges open a mini fridge in an opulent bedroom: “Cristal, beluga, Wolfgang Puck . . . it’s a fuck house.” But there is, on page 309, fuck-you money, which The F-Word dates to 1969 and defines as “sufficient money to give one personal freedom, esp. the freedom to quit one’s job.” In other words, to retire.