Illustrations by Jorge González

On the first of June, 1901, Anton Pavlovich Chekhov, a doctor and writer of short stories and plays, a famous man who also suffered from tuberculosis of the lungs and intestines, sat at a table, surrounded by other consumptives, before a bottle of mare’s milk and an enameled tin cup.

It was his first morning in Aksionovo, at the Andreev sanatorium, a thousand miles from Moscow. He had come with his wife, Olga, on the recommendation of a specialist, who, two weeks prior, had told him in no uncertain terms that great measures needed to be taken, both lungs were damaged with irreversible necrosis, no longer could he expect to forestall the bacillus by simply wintering in Yalta. He had two choices—Switzerland, or koumiss, mare’s milk, fermented by Bashkir herdsmen, and renowned in circles both fashionable and medical for its curative effects.

Count Tolstoy, added the specialist, had also been to Bashkiria, many times, for his nerves.

Chekhov thought of Tolstoy as an ignorant crank who held too many opinions on topics that he knew nothing about, particularly scientific ones—and as a writer of such perfection and beauty as to validate the entire existence of literature itself.

Was there not something closer? he asked.

But no, the doctor told him, for koumiss could come only from the milk of steppe-grazed mares, and it quickly lost its healing properties when the horses were transported from their native land.

But surely Anton Pavlovich knew this, being a physician himself. Surely he must have prescribed it to patients of his own.

In answer, Chekhov coughed and shook his head. For his patients were poor, paid no fees, and could not afford the journey, let alone the sanatorium. When he had recommended it—and there had been a few times—it was to friends only, advanced cases for whom other therapies had failed.

The journey had taken six days. From Moscow, they had endured a train whose windows wouldn’t open, mutinous passengers, two errors in the timetables, a crowded steamship, a night in the rain and on a quayside floor where an old man spat behind a sheet that functioned as a bedroom wall. Somehow, in each town they entered, well-wishers, preternaturally alerted to his presence, came to harry them, and yet in Aksionovo, they couldn’t find a driver, and had to rustle up a carriage from the alehouse. By the time they arrived at the sanatorium, it was midnight and the doctor had gone to sleep. It took a long time before the bell was answered by the sound of shuffling footsteps.

The door opened before a servant so pretty that Anton, for a moment, found himself speechless. As Olga spoke their names, the girl’s eyes widened. For the doctor had been waiting. They all were waiting. And there was mail, and telegrams, and the other guests . . .

Chekhov felt a twinge in his chest and touched the flask he carried in his pocket for surreptitiously spitting blood. Not now, he thought, not before someone so lovely, so full of life! But it passed, and the girl was too excited to notice he’d stepped slightly back into the dark. She had heard that they’d only recently been married, the papers had reported it, she would show them copies, yes, in Ufa, they had reported on the arrival of the great writer Anton Chekhov and his newly wed actress, so famous herself. And here they were. How wonderful it was that they should come to Aksionovo on their honeymoon! The koumiss would restore him, for his bride. And even in the dim light of her candle, she seemed to blush.

“Please,” said Olga. “We are very tired.” And the girl took a quick breath as if swallowing the many other things she wished to tell them, slipped into a pair of bast sandals, and led them on a path around the house. There were no lights. She brought the candle, though it wasn’t necessary, the sky was clear, a half-moon shone on a garden with a silent fountain. The night was calm, not a single leaf stirred in the trees. Even the candle’s flame was still. And she walked so lightly! A grassy avenue rose past cabins set amid the birches. Theirs was at the edge of the grove, with a view over the steppe, the very last—for privacy, said the girl. The doctor felt it was important for his celebrated patient’s rest.

Two steps led up to a porch on which a canvas chair stood folded and propped against the wall. Inside, the room was so spare as to look unfinished. Two stools, a table, a pair of beds. There were no linens or pillows—hadn’t they been told that guests should bring their own?—and it took another hour for the girl to rummage up a set back at the clinic, returning to find the travelers asleep on the bare mattresses. After a moment’s hesitation she left the pile folded by the bed of the man who slept with labored breath, and looked so frail, so ill.

The next morning, Chekhov found himself in the office of the doctor, Varavka. On the wall were photos of dancers and singers, hung like icons around a decorated, light-blue linen towel, similarly framed. Varavka himself was a round man, with red eyebrows and a great red priest’s beard that made up for the baldness of his head.

Exhausted by their travels, the Chekhovs had slept late that morning, rising only with the rapping of the servant girl bringing coffee. It had taken Anton nearly an hour to get ready. His guts had detained him, and he had made the walk with his hat low over his face, suffused not only with a general fatigue, but with the lingering, polluted sense, familiar in such attacks, that he bore with him the air of the latrine.

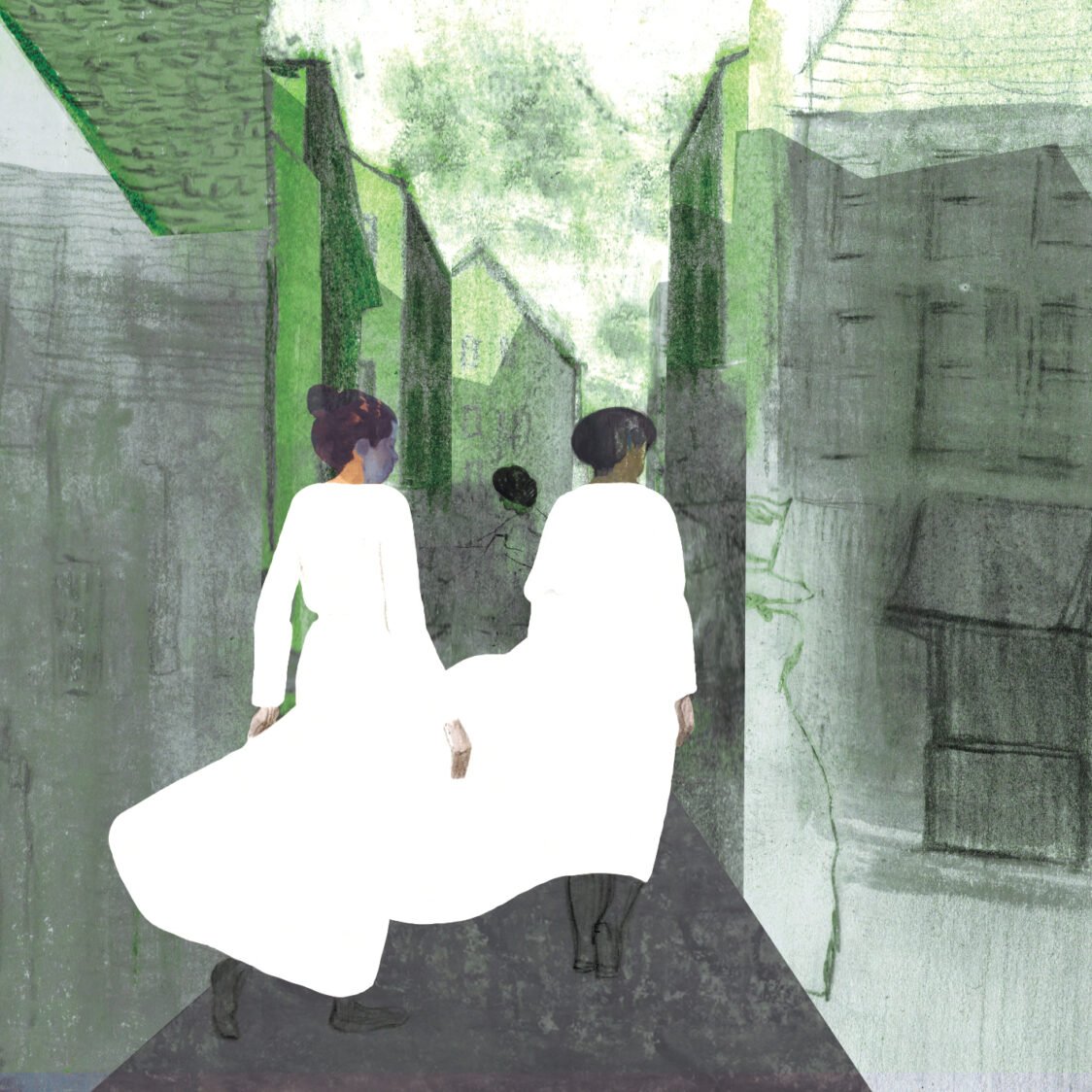

To his relief, they had passed few other patients on the way down to the main house—a man reading in a canvas chair outside his cabin, and three women in white dresses. It was clear they knew who he was; they stared a little before nodding in greeting. But they also must have recognized the grim exhaustion, and didn’t speak.

Compared with the night before, the grounds seemed of a different setting altogether; the enchantment had lifted, weeds overgrew the garden, paint peeled from the house, and the pool beneath the fountain, in which he’d seen the moon just ten hours prior, was green with algae. He had left Olga back at the cabin, and so was greeted alone at the door by the doctor, who—like a man uncertain of the conventions of another’s culture—patted Chekhov, hugged Chekhov, kissed Chekhov’s shoulder, shook Chekhov’s hand, and seemed vaguely annoyed when Chekhov began to cough.

The examining room was on the first floor, a mercy, for he was already so out of breath from the walk that he could scarcely mutter an apology, and he was grateful, upon taking his seat, hands clasped around his cane, that the doctor launched into his greeting. For they were so pleased that he had come to Aksionovo! Everyone was excited, he had so many admirers among the other patients, they couldn’t believe their fortune. Indeed, Varavka, though he had cared for many famous patients, was overjoyed by the honor of caring for not just such a great man but a colleague. He had read in the papers about the timetables, and Agafya—this was the servant—had told him about the carriages, or absence of them, and he was sorry. But here they were! And he was certain Chekhov would find that it was worth the trouble. There wasn’t a soul who wasn’t greatly helped by koumiss, and he rose and took down the framed towel from the wall and brought it over. On it were signatures of other famous guests, which he’d subsequently embroidered, so that they would never fade.

And like a little boy who shares a precious toy, he looked to Chekhov’s face to see what he might think.

What Chekhov thought was that he regretted taking the advice of the Moscow specialist, that Varavka had done nothing to dispel the general reputation of sanatorium doctors as charlatans, and that he was about to have another attack of his bowels.

With a hot wave, the sensation passed. Varavka sat, flourished his paper, and dipped his pen. And Chekhov, who, perhaps more than anything, hated to be treated by another doctor as a patient, spoke first.

“The historia morbi.”

Latin: the story of the disease. He would dictate, and the doctor would take notes.

For two decades of his life, nearly as long as he had written fiction, Chekhov was accustomed to also recording stories of a different kind, a vast oeuvre, set down in clinic notes and hospital reports. Indeed, when asked about his earliest stories, he thought not only of the five-kopek-a-line parodies, but his first case summaries. It was one of these summaries that he gave Varavka now. He did not speak for long: he was, of course, a master of concision. And while he was modest by nature, it was not lost on him that the history he shared was a near perfection of the form, integrating medical knowledge with his gift for narrative tension and psychological insight. And part of him, a little part of him, thought it a shame that such a creation be offered only to an audience of one.

He spoke of his family tree, rotted with tuberculosis, the close quarters of his childhood, his early cough and troubles of the bowels, the first blood, the sudden hemorrhages, copious, terrifying, seizing him each spring in ever-quickening succession. He outlined his fear of spinal tuberculosis, and why he suspected he’d been spared this, just as he’d been spared the horrors that had filled his examining room, tuberculosis of the eye, the mouth, the skin. And he listed the treatments—creosote, subcutaneous arsenic, compresses, cupping—that had failed.

“That,” he said, “is everything.”

Except it wasn’t, and he knew that he could have equally told the story another way, that in the past year and a half, he’d written a single play and begun the story of a dying bishop, but had failed to finish it. That since his childhood he had cared for his entire family, they depended on him like a father, he had a dead brother, a dissolute brother, a widowed mother, a spinster sister who resented his wife. That he felt at times to be a crayfish in a crowded trap. That from all of them he now was fleeing, and at times it seemed as if it were not the bacillus but their demands on him, the world’s demands on him, that took away his air. That one of the reasons he had come was that he had just gotten married, knew that his mother and his sister and his brother questioned his bride’s intentions, and feared his family’s response.

Feared the world’s response, the world’s attentions. That once, soon after his brother’s death, he’d written a story of a dying man whom fame had robbed forever of his simple joys, his cabbage soup, his goose with apples. And that was twelve years back, when he could not have anticipated the lines of petitioners. For interventions, letters, statements, favors, treatments, or simply a moment in his presence. Pieces of me, he told Olga. Consuming me in bits.

He did not tell Varavka this. It sounded ungrateful, and in truth, looking at his life, he could not deny his good fortune. But more than this, he hated the pleasure he knew the other doctor found in taking something from his celebrated patients for himself. Why else the portraits of actresses? More than one of whom, Chekhov realized as he spoke, were dead.

And so, when the doctor rose and motioned him to the examining table, Chekhov said coldly, “Is it necessary? There is necrosis in both lungs. It hasn’t changed since I was examined two weeks ago in Moscow.”

Varavka looked at him, and then to the paper on his desk, now dark with Chekhov’s story. There was a long pause. From nearby came the sound of a bell. The doctor clapped his hands together. Of course, the exam could wait. Now was the hour of the day’s first gathering for koumiss! And that was why Anton Pavlovich had come.

The doctor led him out of the clinic and into a small garden, ringed by birches and a second, smaller circle of apple trees, where long tables were set and the other patients were waiting. There, too, was Olga, whose eyes followed Chekhov with concern. He pitied her, he always pitied her. She had married a sick man, his body had made this clear from the beginning. Always sick, always breathless, his lovemaking constantly interrupted by his coughing or his guts. It was not unreasonable that his family wondered what she truly wanted. He had always held a dim view of marriage; his Collected Works, volumes of which were being prepared that very instant in St. Petersburg, was, on some level, a giant fictional indictment of the institution. You will get a grandfather, not a husband, he had written her before their wedding. But something—love, maybe, or his acceptance of his illness, or maybe the opposite, denial, for what dying man gets married?—something had prompted him to propose their secret ceremony. And here she was, his bride, star of his theater, sitting patiently at the table with consumptives likely pestering her for gossip from the stage.

Conversation stopped. Varavka presented “Anton Pavlovich Chekhov,” and added, with the fanfare of a man accustomed to a doting audience, “Be careful what you say around him—he might put you in a play!” There was laughter, and Chekhov smiled thinly. Around the table, introductions went—Sokolov, a retired general—a lawyer, Voronin—a pair of cousins, pale young men, one broad, one fine—the wife of a Swiss consul—an architect—two men who gave their aristocratic titles—a privy councilor who introduced himself by civil rank. One of the ladies was a singer with a provincial opera; Chekhov hadn’t heard of her. The rest of them were wives and husbands.

He sat, received the greetings graciously, grace being both his gift and curse. Silence followed. He caught an exchange of glances, as if the gathered party was waiting to see which of them was bold enough to speak. And he knew what was going through their minds, for he had been presented to many circles, many tables. Should they tell him that they loved “The Grasshopper”? That they’d seen The Seagull in Moscow? Read “Kashtanka” to their grandchildren? He could see it in their bearing and their faces, knew that when each one returned from Aksionovo, “Anton Pavlovich” would be the story that they told. For they had met a great man, and when he was weak, yes, maybe even dying. Yes, truly Chekhov! And on his honeymoon! And yet so ill, as sick as everybody else.

When he was a young doctor, Chekhov had a patient who had once served Pushkin at a coaching inn. The man was very old, dying of a cancer of the lungs. Somewhere in the vast world were his children and grandchildren, and yet as he died, he spoke of Pushkin, and how Pushkin had carried himself so elegantly, and asked for a second glass of water, and how Pushkin had finished his soup but barely touched his rice.

At each place at the table were a bottle and a tin cup, and here and there were plates of strawberries. A faint, sour smell rose from the milk. Four times a day, thought Chekhov. Was he to perform the great man here, in the wilds of Bashkiria, where he had come to rest? Voronin wore dye in his beard—Chekhov could see it on his cheeks. And the white dresses hung so unnaturally on the women, as if they thought that they were beautiful and didn’t know that they were sick.

Olga must have sensed his exhaustion, for beneath the table, she took his hand. And he readied himself to grant them what they wished.

But the general was the first to speak.

Was it true that it was Chekhov’s first time drinking mare’s milk?

Well, yes and no, said Chekhov, relieved, and maybe even a little—not disappointed—surprised, to be asked about something other than his writing. Yes, in the market, but not on the steppe, not at a sanatorium.

“A virgin of koumiss!” said the general, and there was laughter, and some blushes from the ladies at the table, though they didn’t drop their eyes. Yes, they were all staring at him, and then he understood that it was so they could watch him drink. He looked at Olga, and then over to the doctor, who himself had taken a seat at the table. Very well, he thought, and took the cup into which the general had ceremoniously poured the milk. Now, closer, the smell was actually sickening. He sipped.

“All wrong!” the general told him. “Not slow, my writer! No, not gently! In a gulp!”

Why, this is so absurd, I wouldn’t dare to put it in a story, thought Chekhov, as he raised the koumiss to his lips.

It tasted, as he recalled from years before, like sour chalk, and whey, and beery, rotten cream.

“Well?” asked Sokolov.

They’ve gone crazy, thought Chekhov. And he wished to shout out that they were dying, that tuberculosis was implacable, that nothing could cure them, that the best they could hope for was not to be unduly tortured on their way to death. But then something was happening, a breeze passed through the apple trees, he blinked twice, the birch leaves shimmered like falling coins, a jackdaw called, the ruffles on the blouses of the women fluttered once, together. Olga reached over and handed him a napkin. “Your beard,” she said, and laughter followed. “Another?” asked the general. The man poured, Chekhov drank, the bubbles from the ferment seemed to rise into his eyes. How strange! he thought. It couldn’t be, but he felt better. Impossible! The koumiss worked by fortifying the body—this took weeks or months. And yet something was happening. He drank, tears filled his eyes, a faint effervescence; it seemed as if he were staring at the exultant party from beneath the shifting surface of a pond. Around him was the smell of strawberries, lavender drifted from the neck of the wife of the Swiss consul, and there was rose, and lilac—yes, the women all wore perfume, how had he not noticed? He drank again, the taste had changed, sweeter now, as if he could perceive the very grass on which the horses fed.

He wiped his lips. Olga was looking at him, quizzically, and it occurred to him that what was happening now was not entirely new, but that it was simply a long time since he’d been drunk.

Of course! What a fool not to have thought of this immediately! The ferment wasn’t strong, but given how frail he was, how thin, how long he had been banned from wine or spirits. . . . Oh, how pleasant it was, he thought, to be drunk outside at midday, to be giddy in the sunshine. And with such companions! Now, halfway through the bottle, he loved his companions, such good, kind, joyful people. And they asked nothing of him, no introduction to an editor, no political statement, no loan, no intervention with the police for a cousin’s wayward friend, nor did they question his marriage or his bride’s intentions. No, he had been welcomed at the table simply for what he was, a consumptive, an eater of strawberries, a drinker of mare’s milk.

From around the table came the sound of final slurps and clinking cups and drinkers rising. An hour had passed, the morning koumiss was finished; he had been so lost in the sense of well-being that he had scarcely noticed. The doctor announced that he was going to fish in the river. Sokolov would join; could Chekhov come? But Sokolov’s wife was quicker. “Stepan Andreevich! This is a married man, and on his honeymoon. And you would take him from his wife?”

Now most of the guests had left the table. The cousins’ arms were interlocked. Voronin had his arm around his wife, and as they sallied forth her dress snagged briefly on the roses. It was almost obscene, thought Chekhov, this coupling. He felt as he once had in certain houses back in Moscow, when the meal ended and the customers would choose the girls of their desiring. For were the cousins really cousins? They looked into each other’s eyes so dotingly. And what was the little wife of the privy councilor now whispering that made his neck turn red?

They followed, the white dresses swayed like tipsy ghosts, someone stumbled into the lilacs. It was warm and still, and as they walked up the avenue that ran between the cabins, he watched the couples drift inside, swaying, one by one he saw them draw the damask curtains, the men unbuttoning their cuffs, the women reaching up to pull their hairpins from their hair.

Inside, he closed the door. His new wife turned to him. “I think,” he said, “that I have been remiss in my appreciation of this miraculous drink.”

Gently, he drew her body against his.

“Oh dear, it really is miraculous,” she said.

They became great nappers, loungers, laze-abouters, drinkers of koumiss.

The hours vanished. They left their watches entangled in a suitcase, ticking in syncopation, until first one, and then the other, stopped. Woke with Agafya’s knocking when she brought them coffee in the morning, or—when he was too drunk, too sleepy, to go down—his milk. And he would drink it there on the veranda, bow to the girl and set the tin back on her tray, and, satiated, stomach sloshing, return inside, where Olga waited. Naked but for their bedsheets, eyes inquiring, It’s nearly noon, would he like to take a stroll, or something else?

And the answer, always: something else.

It was astonishing, he thought, as the days melted into one another, and they moved dreamily from bed to table and back again. Had someone asked him what to expect of convalescence, he never would have thought to say: lasciviousness, an uncontainable, colossal lust. At first, he thought that it was simply drunkenness. Drink provoked desire, didn’t it? Persuaded lechery: and this on the authority of no less than Shakespeare. But as the days passed, and he found his bowels settling, and flesh returning to his bones, five pounds then ten, he found desire rushing back. And not one of his professors had mentioned this, nor could he recall it from a textbook. A secret! thought Chekhov. And he told himself that he should write it: Chapter 42, the consumptive on return to health will find himself sixteen again but with an old man’s knowledge. He will become a satyr, will forget his rotten lungs, and in the wind, he’ll hear the sounds of smacking lips. Will tangle in the sheets, and drive the mattress off its wicker frame, and wake only to find himself seized once again by lust.

Will be rendered speechless by a missing button on the blouse of the wife of the Swiss consul, and the way the wind brushed back Agafya’s hair to show her collarbone. And the wet, laboring fingers of the milkmaids, and the milk smell of his wife.

For Olga also drank it. At first, worried about her weight, she’d taken only sips of the elixir, before she had relented, joining the patients in their revelry. In the mornings, rising from their bed, he watched her palms appraise her breasts, the gathering roll about her waist. You do not understand, she said, in answer to his murmuring appreciation. You do not have to face the tailor, the gossip of the other actresses, the papers. It is not the same for writers, the world does not ask for slender ankles on the men who write the plays. But then two hours later, sitting with him naked on their stools, koumiss before them, she watched him, black-eyed, before they locked their arms and drank.

And as the days passed, and their astonishment at such a convalescence settled into a calmer, measured bliss, they wandered.

By then they had come to know the other guests and Chekhov sensed his novelty had vanished. Indeed, the others even seemed to have forgotten who he was. Sometimes, the consul’s wife, a reader, gushing over Tolstoy or Turgenev, would pull up short, but this was rare, and it amused him. When at last she spoke of his plays—and she’d seen all of them, well, the famous ones—it seemed as if they were just discussing friends they held in common. And she would leave off from Uncle Vanya, and tell him of her own Vanya, her boy, who’d had such trouble at the academy, and of how Natasha in Three Sisters reminded her of her mother, who had torn up their orchard simply because the trees were old and rotted, though they still gave such fine fruit.

He suspected that she loved him. Sometimes, when he was walking, she mysteriously appeared. It amused him, and even Olga, when he woke her in their bed, would tease him: “Go to your girlfriend, Anton!”

And then: “Antosha, it is the middle of the night. I also came for rest . . . Dearest, won’t you tire out?”

But he’d been tiring out for seventeen years. Daytimes, leaving his sleeping wife, he joined the doctor on his fishing expeditions, listened to the general tell of his campaigns. And while the doctor enjoyed talking about his famous patients, he enjoyed talking about fishing even more. The truth was—he confessed, sotto voce, in the middle of the stream, with only Chekhov and Sokolov to hear him—he had come to the sanatorium because of the fishing. You could find roach and dace and ide, and pike in the lakes, and even perch and taimen. Yes, he told Chekhov and the general as he rowed upstream, his strong, pink arms flexing against the oars, he lived for fishing, to cast for trout in the rapids, to use a long line, to watch it fall so softly on the water. But just as much he loved the slow water, to fish for eelpout with a minnow—yes, that was the best, to catch a minnow and then use it to catch an eelpout, though he always felt a little sad to see the creature twist. On good days, he gave his catch to the cooks to prepare for the patients. His eyes lit up when he spoke, and Chekhov forgave him the wall of photos and the embroidered towel. For he loved being the person he was then, a man hearing a story of a fish.

Sometimes, he tried to get a word in—who could resist the pleasure of such recollections? He, too, had spent so many hours on stream banks; he, too, had felt the tension of a burbot’s mouth around his fingers. But he had used up the best of his stories in his fiction, and he feared the doctor might remember this, and abandon his soliloquies. And then the conversation would no longer be about burbot; it would be about Chekhov. So he was quiet, and lazily drew figures in the sand.

The river was deep and wide. When they stopped to picnic, he waded into the water; twice he swam. He tired quickly. The first time, swept away, he had to grasp a pair of drooping willow branches, and collapsed upon the bank. But it was worth it, and a second time, on a very hot afternoon, when Sokolov had drifted off to sleep, and even the doctor had ceased his gabbing, Chekhov rose, and stripped his shirt and trousers and walked into the swift, warm water, and let himself be carried off.

Downstream! The river cast a wide arc around the sanatorium. He passed the willow that had saved him and a beach where Voronin and his wife were bathing, her suit lowered over her shoulders, and then another patch of sand where Agafya was washing in the water, her wet blouse clinging to her breasts. He floated past the stables where the horses watered, and the grassy fields before the clinic and the cabins, now so small, so swiftly retreating. From far off, he could hear the snorting of the horses. A herdsman, watering his mare, looked up, and seeing the drifting man, dropped his reins and made to dive in after him, but Chekhov shouted, No! No! Leave me! and he threw his arms back in pleasure to prove that he was well. He drifted, he couldn’t decide whether the sun or the water was more wonderful, the river narrowed, quickened, before it slowed into a deep warm pool. There, children were playing. They stared, but let him be—they understood the current’s joy and didn’t think he needed saving. And he was off again. He rolled like a seal, and dipped his head, and let his feet down, where they dragged through the silty, silky bottom. He hadn’t had such joy from swimming since he had written about it. He was humming “Largo al factotum,” which was odd, because he’d never loved the opera, though it occurred to him that he had never listened to it nearly naked, floating in the sun. It also occurred to him that he might write a story of a man, near death, who rediscovers an unexpected pleasure of his childhood, a taste, a smell, a melody—and he saw the entire plot before him, save the obvious ending, which seemed so trivial and trite.

He passed another patch of forest before the river opened fully onto the steppe.

For a moment, he felt a wave of vertigo—there was nothing to the left and right but grass, so flat, so uniform. Should he get out? But the warm sun lulled him, and he thought, What if I went this way, until my breath failed me, and let the current decide whether it would pull me under or carry me on?

For a long time there was nothing but steppe, and then a single hut appeared. Fearing there might not be another for miles, he paddled to shore, rested, rose, and walked up to the house. A farmer was at home, utterly unfazed by the dripping man who explained, breathlessly, his situation. But the sanatorium wasn’t far—the bends of rivers are deceptive—and when the cart returned him, the doctor and Sokolov were still out fishing. Olga was napping in a chair outside their room, her pink blouse faded to white but for the armpits. When he woke her, she mumbled dopily that she could taste the river on his lips.

He didn’t sleep that night. Slowly disentangling himself from his wife, he rose and crossed the room and went out to the veranda and looked across the plain. Cricket song rose from the grasses, from somewhere came the serenade of corncrakes and the distant snorting of a horse awakened from its slumber. His skin had burned that day; it felt as if the sun were still upon him. How wonderfully sore his shoulders were! Yes, it seemed as if he’d stepped into another’s body. He recalled the river’s sway, and Olga’s warm, milk-softened hips as he had moved above her in the dark. And here he had thought himself sick, when really this was all he needed: milk, his wife, a river. Fourteen pounds in but a single month! And if he still coughed blood, still found it ribboning the koumiss when he took it from his lips? It didn’t matter. No, he couldn’t wait until the dawn, he would run into the water, he would float and sing, Olga would come with him, this time they would go for miles, he would write his sister, his mother, his brothers, and beseech them to join him. And together they’d follow him, their heads bobbing, their cheeks kissed by the sun, his brother’s cap floating away, his sister’s dress blooming, his mother’s hair spread out upon the stream.

It was then that he realized he was crying. He tried to stop, but once it started, he couldn’t hold it back. For he could see it so clearly then: Olga and his mother and his sister and his brothers, and now even his dead father, and his dead brother, floating, laughing, their bodies tiny in the vastness. Day after exquisite day, July, August, the flowers fading in the heat, the trees beginning to turn, the restless birds, September and the grasses yellowing, and then the winds, the cold wind coming down from the north, the snow, and still they would float, still they would spin, as the river slowed, and the steppe darkened, and the ice gathered in their hair and across their shoulders, until one day, very soon, at an hour indistinguishable from the last and from the one that followed, the floes would seize and the great and sweeping waters would draw slowly to a halt.

The following morning, he told Varavka he would be leaving. The doctor seemed not to hear him, and spoke of plans to ride out to a tributary where he’d once caught taimen.

“The size of a lamb,” said Varavka. And then: “Two months, it was agreed upon. Think of all your progress.”

But his decision had been made. There was no need to draw it out.

The other patients knew before he told them; he felt them turn on him. In a stroke, they seemed to age, as if they’d worn the costumes of living people but now were dying once again. In the sun, he saw the hair dye glistening on Voronin’s cheeks. The consul’s wife no longer watched him as she sipped. The cousins came and handed him their address. If he could send a signed photograph?

Varavka, at last conceding, planned a goodbye party for Thursday. Wednesday, avoiding Agafya as she repaired the doctor’s fishing nets out by the fountain, Chekhov bribed a porter to call the carriages from town.

They slipped away under the cover of night. As they rumbled down the road, the ranks of birches rustled above them. Olga looked at him; he took her hand. He wished to reassure her, to promise other travels, but just then, they heard a shouting and their carriage stopped. The crickets’ song resumed. A horseman drew up to their side.

It was Varavka. He was breathless, a coat was thrown over his nightshirt, and he wore sandals on his feet. His face was red. Instantly, Chekhov felt guilty for the deception. He readied an excuse: a crisis in the theater, an illness at home. For the least he could have done was thanked the doctor for his friendship, his stories by the river, the fish!

Breathing heavily, Varavka reached inside his coat. Reached like one reaches for a pistol, and his tussled hair and his wild gaze made Chekhov, for a moment, wonder if he had come in vengeance for his wounded pride.

Instead, he removed the light-blue linen towel. “You did not sign it!” he said, and jumping down from his horse, laid it over Chekhov’s knees. He had also brought a pen and an inkpot. He pointed to a spot beneath the signature of Natalia Stepanova, the opera singer.

The towel took the ink up greedily. Chekhov had to dip the pen three times. When he finished, Varavka held the towel to the moonlight. How excellent, he said approvingly—yes, he would have it embroidered straight away!

“And you will send a photo, also, won’t you? We will hang it in the hall!”

And then with a swiftness that belied his size, he heaved himself back on the horse, touched his hand to his heart, once, twice, and with a kick rode back into the night.