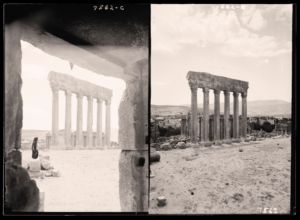

The Temple of Jupiter, with the Temple of Bacchus in background, Baalbek, 1936. Courtesy the G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress

In Baalbek, Lebanon, across from the Roman ruins the city is known for, lies an old hotel called the Palmyra, its façade mantled in dark climbing vines. I first encountered its image when I was eight, in a yellowed old book: Histoire de Baalbek, my great-great-grandfather Mikhail Alouf’s chronicle of the city. The opening page, featuring a photograph of the six pillars of the Temple of Jupiter viewed from the triad of arched windows fronting the Palmyra’s balcony, was printed on a sheet of pink paper. Mikhail, the ruins’ first conservator, had devoted his life to documenting their every last stone. According to family lore, he had purchased the Palmyra at least partly because he believed a Roman amphitheater lay buried beneath it.

The pink page was one reason the hotel was always that color in my imagination, but another was the pink façade from Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel. The Palmyra owed part of its renown to the Baalbeck International Festival, an annual series of music, theater, dance, and opera performances that was held among the ruins from 1956 until the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975. Over the years, the hotel hosted many of the festival’s famed guests, earning it a reputation as a kind of Grand Budapest Hotel of the Levant—a haunt for musicians and poets such as Miles Davis, Fairuz, and Jean Cocteau. The festival years were emblematic of Lebanon’s golden age, a period of prosperity and cultural vibrancy during which Beirut’s hospitality, free press, and cosmopolitanism responded dazzlingly, as Edward Said once put it, “to our needs as Arabs in an Arab world gone prisonlike.” By the time my grandfather’s cousin sold the hotel, in 1985, this age was long past, and the music of my father’s youthful summers at the Palmyra had given way to the din of mortars and shells, a familiar Arab story.

Photographs of the Palmyra Hotel. The dining room; Roman busts in the entrance; Room 27 © Tanya Traboulsi. A drawing by Jean Cocteau leaning against a radiator in the dining room © Brett Lloyd/Scenery

I grew up mesmerized by the idea of the Palmyra, but I had never been there myself. It existed in my mind alongside a host of other puzzling images of Lebanon, such as the Ring, a no-man’s-land section of the Beirut highway girded with snipers, and the Green Line, a name for the thick strip of foliage that, during the civil war, grew between East Beirut, where my father lived, and West Beirut, where my mother did. Both my parents left Lebanon for Paris in 1989, at the tail end of the conflict. Growing up in our Parisian apartment filled with Lebanese food, music, and televised footage of things exploding, I oscillated between two portraits of my home country: my mother’s jaundiced view of Lebanon as a serial abuser we should disentangle ourselves from, and my father’s dutifully optimistic one, which saw it as a sickly child in need of our help. For her, Lebanon’s endless crises were demonstrative of the real country, too saturated with sectarian divisions to ever hope for freedom from foreign control. For him, they remained deviations from the sunlit beacon of cultural pluralism Lebanon had once promised to be.

Even though I knew that the purported golden age had collapsed into a civil war that pitted Lebanon’s various religious sects against one another in a cycle of internecine violence and ever-shifting alliances involving the Syrians, the Israelis, the Palestinians, the Iranians, the Saudis, and the Americans, it was always my father’s vision that I remained most drawn to. I visited the real Lebanon twice a year, to see my grandparents, but the rest of the time I dwelled in my imaginary Lebanon—a country of ancient temples and vibrant hotels. In some recess of my mind, I suppose, I really did expect to return one day to this version of the country, like a song coming home to its tonic after a protracted modulation.

Then, in May 2023, my aunt Carine, who lived in Beirut, passed away. She had spent her last few years weathering each of Lebanon’s successive nightmares while my father exhorted her to leave. As I boarded my flight out of New York for her funeral, I felt an unfamiliar resentment for the place where she had slowly come undone. Lebanon was reeling from one of modern history’s worst financial collapses. The country was so politically divided that it seemed intermittently to be on the brink of another civil war, and Beirut was still gutted by the massive 2020 explosion at the city’s port, which killed hundreds. During the day, my family and I distributed the schoolbooks and medications we brought for our friends who lacked foreign passports. At night we boxed up my late aunt’s belongings.

Among these was a copy of Histoire de Baalbek. My aunt, my antiquarian grandfather, and I had often talked about going to Baalbek together, to undertake an archaeology of our family’s history in a region now known primarily as an operational base for Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shiite militia that serves as the crown jewel of Iran’s network of regional proxy armies. But our trip was always scheduled for that nebulous part of the Lebanese calendar known as “when things calm down”; and things had never calmed down. For years we had glimpsed Baalbek’s ruins only in headlines of the rockets-slam-historic-city variety, overspill from the Syrian Civil War.

Now, perhaps because the national atmosphere of imminent catastrophe had manifested in the form of a familial one, I had the anxious feeling that my chance to visit the Palmyra Hotel with anyone who remembered it was fading. The Baalbeck International Festival, I learned in the weeks following my aunt’s funeral, would be taking place in the temples in July; after a twenty-two-year hiatus due to the civil war, it had resumed in the late Nineties, and had become a popular destination for tourists and members of the diaspora. My mother knew Rima el-Husseini, who now watches over the Palmyra Hotel, through a mutual friend, and offered to call her to book us a room. My father, dazed and grieving, seemed open to being enlisted in an expedition.

On the first of July, I emerged from the bed I’d stagnated in for weeks while mourning my aunt, and set out for Baalbek with my parents. I wanted to finally see the fabled hotel where my family used to live, to glimpse my home country from what felt like its long history’s vanishing point.

Our first stop was the home of my great-aunt Leila, a few miles north of Beirut. Leila had grown up in the hotel and distributed programs for the first festival in 1956. She was turning ninety-nine that summer, but none of us had wished her a happy birthday, deterred by the Lebanese expression “may you live to be one hundred.”

The hotel, I learned from Leila, was built in 1874, and so is actually older than the country, which then was split among a number of Ottoman provinces. In their years at the Palmyra, my family had witnessed many major phases of Lebanon’s history: 1922, the year my great-great-grandfather purchased the building he would transform into the hotel, and when Lebanon’s modern borders were drawn up under the French Mandate; 1943, when the country declared independence as a multi-confessional, multicultural state, and the antiquities museum Mikhail built in Baalbek celebrated its first-year anniversary; the so-called golden age, when jazz illuminated the ruins and my father spent his summers at the Palmyra; and finally, 1975, at the beginning of the civil war, when the festival stopped and the Alouf family started trickling out of Baalbek until, in 1985, its last remaining member sold the hotel.

The sale remained a fraught subject in my family. Stories ranged from one of simple debt, as the festival’s interruption during the war emptied out the Palmyra’s guest rooms and the growing presence of Hezbollah kept alcohol from being served at the bar; to the killing of the Maronite maître d’hôtel’s son and persistent threats against Christian families like ours; to apocryphal accounts of fires and narrowly dodged bullets. My father tended to avoid these discussions, regarding them as reminders of a time of religious division best left to rust away alongside other ugly remnants of the war. Leila, on the other hand, was still as livid at the family’s decision as if it had been made mere moments ago in an adjacent room. “Why, why?” she said with fresh shock whenever the topic came up. “You can’t put a price on history!”

Leila showed me some keepsakes strewn around her apartment: the copy of a note Cocteau had left in the Palmyra’s guest book describing the hotel’s balcony as an “ideal place for poets’ souls to take their flight,” as well as a photograph of Fairuz, widely considered to be Lebanon’s national singer, divinized with light before the six pillars of the Temple of Jupiter. A handwritten caption read fairuz—the seventh pillar of baalbek—1957.

“Those were the happiest days of our lives,” Leila told me. “Baalbek was an international city, full of foreigners pinching themselves before the Roman ruins.” She described the colorful dresses of her favorite guest, a member of the Ethiopian royal family, and recalled the year her cousin was invited to star alongside Jeanne Moreau in one of Cocteau’s plays. “It was too good to last,” she said.

I asked Leila whether any traces of the family’s past remained at the hotel. She mentioned a protruding slab of rock a short walk away from the Palmyra, which Mikhail had apparently repositioned to mark the spot where he believed the entrance to the Roman amphitheater lay buried. She also urged me to seek out Abu Ali, the last surviving steward from the hotel’s prewar days, who had joined the staff in 1968 and whom she called the “soul of the Palmyra.”

Before I left Leila’s apartment, she handed me a gigantic tray of kibbeh labanieh (in Lebanon, someone is always offering a gigantic tray of kibbeh labanieh), along with a thick Arabic manuscript that my father had never seen before. Its title was The Alouf Family, or A Glimpse into the History of Baalbek. This was a copy of Mikhail’s unpublished autobiography, Leila explained, the substratum to his monumental Histoire de Baalbek’s six editions. Leila suggested we use the manuscript as a kind of place mat for the kibbeh, to keep any yogurt from spilling on the car seat on the way home; my father, having seemingly inherited more of his family’s conservationist spirit, asked for a napkin instead. Leila waved him away. She had no need for documents from the past, she said. She had lived it.

Over the next few days, as arrangements were made to stay at the Palmyra for two nights and attend some of the festival’s performances, my father and I read segments of Mikhail’s autobiography, from which we learned of his attempts, after the end of World War I, to endear locals to French culture. He hoped to integrate Baalbek into what would become French Lebanon, under the conviction, he wrote, that France would be a “tender mother” to the region’s Christians and Muslims alike. For these efforts, Mikhail briefly lost his position in antiquities preservation, and in 1926, only four days after his daughter Hélène gave birth to my grandfather, he went into hiding as rebels fighting against the French in Syria made their way to Baalbek. Although many Christian families had fled, Mikhail did not want to abandon his bedridden daughter, leaving her only once the rebels stormed the Palmyra, looking for him. While Mikhail managed to escape by climbing out a window and taking refuge in a nearby nunnery, the men took his son hostage, and Mikhail was not able to ransom him until several days later.

Mikhail glossed over the negotiations in half a page, devoting the next five to his attempts to return stolen statues to Lebanese museums and beseech foreign antiquities directors for help in restoring Baalbek’s temples. In this he was encouraged by his success with Kaiser Wilhelm II, whom, per family legend, he had persuaded in 1898 to organize the ruins’ first-ever excavation. At fifteen, Mikhail wrote, he had engraved his name on one of the temples. The enduring guilt from this defacement was what had sparked his lifelong devotion to the ruins’ conservation.

Some days later, reading an old newspaper article, I found that Mikhail’s sentiment had been shared by Ali el-Husseini, the man who had bought the hotel from my relatives. In a notebook where he kept pictures and mementos from the Palmyra, el-Husseini, according to the article, had written the following: “No one has the right to touch these stones, except time.”

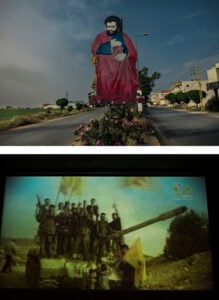

The road to Baalbek was lined with placards memorializing martyrs, the deceased members of Hezbollah whose portraits are adorned with the party’s yellow flag. The Bekaa Valley is not only one of the Party of God’s strongholds, but also its ideological birthplace, where Iran and its Revolutionary Guards helped train Shiite militants shortly after Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982. Hezbollah would successfully push Israeli troops back over the border in 2000, and over the next two decades, it would grow from a local militia into one of the Middle East’s most fearsome armies.

Hezbollah shares its chronic corruption and misrule with the other militias turned parties that have hollowed out the postwar Lebanese state. But in every other respect, it represents a singular threat. The only militia that was permitted to keep its weapons after the civil war (on account of its ongoing fight against the Israeli occupation), Hezbollah today operates as a de facto state within a non-state, deciding Lebanon’s fate in tandem with clerics in Tehran. Having overtaken the country’s security and political apparatuses, it has essentially offered up Lebanon as an arena for Iran to freely pursue its regional ambitions. In addition to engaging in regular border clashes with Israel, the group has supported Bashar al-Assad in his decimation of Syrian rebels and has been accused of assassinating Lebanese political figures who oppose Syrian or Iranian influence in the country. Hezbollah may also bear some responsibility for the Beirut port explosion, but the investigation into the matter has repeatedly been quashed by political interference. (In 2021, after a prominent Shiite activist, Lokman Slim, called Hezbollah “the first accused” on TV, he was found dead in an abandoned car, shot once in the back and five times in the head.)

For these reasons, Hezbollah’s many critics in Lebanon often refer to the group as a cancer on the country. For some Lebanese, however, especially in the Shiite community, Hezbollah remains not only the emblem of resistance against Israeli aggression, but also a major provider of social services, running hospitals, health centers, and schools in the south, the Bekaa, and the suburbs of Beirut.

My father and I left behind the tall cedars of Mount Lebanon, and the fields of the Bekaa Valley slowly appeared below us in brown and green patches. The closer we got to Baalbek, the more our surroundings began to feel like a parody of the beautiful international city of Leila’s descriptions. Roadside shops alternately sold men new tires and women new faces, while storefront signs in butchered French were the only trace of the tender motherhood Mikhail had hoped for. At one point, we saw Canada Gas Station sandwiched between Brazil Supermarket and Japan Motors. Lining the curb next to them were more placards of martyrs, and billboards featuring the longtime Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah. (He would be killed in an Israeli air strike the following year.) There were also billboards featuring Bashar al-Assad and one that was apparently misprinted, with two Putins slightly offset from each other, holding Qur’ans next to a caption in Arabic and Russian reading guardian and protector of religions.

As we neared a military checkpoint outside the city, my father slowly downshifted and parked near the entrance to the golden-domed (and purportedly Iran-funded) Sayyida Khawla Shrine, its Persian blue tiles gracefully inscribed with calligraphy. Adjoining the shrine, we found, was a Hezbollah “museum,” whose centerpiece was an illustration of a Dome of the Rock–shaped donation urn converting coins into a hail of bombs descending onto a shattered three-dimensional Star of David. Other works on display included a photo collage of Gamal Abdel Nasser, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Hafez al-Assad, and Omar al-Mukhtar, accompanied by a selection of rocket launchers, which we briefly contemplated before hastening back to the car.

Top: A sign depicting Abbas al-Musawi, a co-founder of Hezbollah, along a road near Baalbek, May 2024 © Diego Ibarra Sanchez/New York Times/Redux. Bottom: A photograph of a film projected in a theater at a museum operated by Hezbollah at the site of a former secret base in southern Lebanon, October 2012. The film depicts Hezbollah fighters during an operation against Israeli soldiers in 2006 © Moises Saman/Magnum Photos

After we were waved through the checkpoint, the six pillars of the Temple of Jupiter finally appeared in the distance. Their moldering forms were strangely soothing. Here, in this abnormally ruined country, were some normal ruins at last.

Baalbek’s Roman remains, among the largest and best preserved in the world, are also among the most mysterious: the Temple of Jupiter sits atop three megaliths weighing around a thousand tons each. No one knows how they were transported to the site—no Roman crane was capable of lifting such a weight. As for the buildings themselves, little is known about who commissioned or designed most of the gigantic complex, only that it was constructed between the first and third centuries, when Baalbek was known by its Greek name, Heliopolis—the city of the sun.

On the steps leading up to the propylon, my father and I found a tour guide sitting alone, chewing tobacco. His name was Mohammed. Waving to the vast expanse behind him, he said: “It’s a side of rice next to this, isn’t it?”

“What’s a side of rice?”

“Athens.”

Perhaps owing to its Greco-Roman past, Baalbek tends to call up the Lebanese national pastime of disparaging Greece, which is regarded locally as something like a former high school rival who went on to tremendous, undeserved success. “What does Greece have that we don’t?” asked Mohammed. “Our sea was ten times bluer than theirs.” The Parthenon, he said, was “a Toyota” next to Baalbek’s Temple of Bacchus.

My father hired Mohammed for a tour of the ruins, and he led us from the Hexagonal Court of the temple to the Great Court, where fallen pediments and plinths lay scattered across the ground. There, on a stone block, I found, engraved in serifed letters, the inscription my great-great-grandfather had made at fifteen. I asked Mohammed if he knew anything about the Palmyra Hotel. Only that it was older than the country, Mohammed said, built by a businessman of unknown origin so that its balcony would precisely frame the six pillars of the Temple of Jupiter. When I asked Mohammed if he knew the businessman’s name, he mumbled something unintelligible. “What?” I said. He sighed. “Perikili Mimikakis.”

Bidding farewell to Mohammed, my father and I sought out the site of my grandfather’s old antiquities shop, where he once sold Ottoman rings, Byzantine crosses, and Roman coins. But, like many places my father recalled from his childhood, it was gone. The Greek Orthodox church was deserted, too, as was its cobblestone courtyard, where my father and his sister had raced each other on their blue bicycles. The traditional Lebanese houses with green shutters and red-tiled roofs were now splattered with mustard-yellow signage for OMT, one of the services the diaspora relies on to send money home from abroad. Then, just as I began to suspect that the hotel itself would be missing, my father said, “Ya Allah. We’re here.”

Only the letters pa and r of the hotel’s sign remained, and a dozen solar panels now sat atop the roof. But otherwise the hotel looked just as it did in the photographs, though without the trace of pink. The balcony’s three windows, whose view of the ruins I knew so well, were twined with lush swaths of wisteria. To the left of the hotel were the narrow streets leading into the city, webbed from above with tangled nets of dysfunctional power lines, and to its right were four empty tanks belonging to the Lebanese army, stationed by the quarry where the three megaliths had been excavated. I stood at the hotel’s gate, hesitated for a moment, and entered.

The Palmyra’s entrance hall was dimly lit. Fragments of a broken armrest lay on an otherwise empty table, and paint was flaking off the walls. Antique chandeliers and sconces, only a few of which seemed to function, wilted from the walls and ceilings like dying flowers. A few tourists, having arrived early for the festival, wandered around in awed silence.

In the main hall was a display of memorabilia, including Cocteau’s original note for the hotel. There were photographs of festival performers, like Ella Fitzgerald and Rudolf Nureyev, and signatures of figures whose visits I had not known about: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Charles de Gaulle, T. E. Lawrence. The bar was lined with empty liquor bottles, above which hung posters advertising an exhibit celebrating Egyptian cinema and the Venetian Carnival—vestiges not so much of any particular place as of a hazy lost world of culture.

Suddenly a voice resounded behind me.

“Mikhail Alouf?”

I turned to find an elegant dowager in a long, flowing blouse, pointing at the Histoire de Baalbek I held in my hand. She introduced herself as Marie-Reine, and after trudging through a thicket of family relations we established that she and I were likely related in some distant way. Marie-Reine, who had stayed at the Palmyra during the festival’s heyday, took my hand and walked me through the hotel of her memories, the dances in the cavernous dining hall, the all-night lyrical improvisations of the poet Talal Haidar in the courtyard. Every time Marie-Reine’s eyes met mine, she seemed to experience an almost physical pain, as if assaulted by my presence, a reminder of where—or rather, when—she was. When I asked her for more details about the family’s departure from Baalbek, she said only that the past was “too painful to discuss.”

A ceiling fragment from the Temple of Bacchus, Baalbek, c. 1945 © George Hoyningen-Huene Estate Archives. Courtesy International Center of Photography, New York City. Gift of Nancy White, 1980 (220.1980)

I joined my father in the courtyard, where he had taken a seat at a table near a hexagonal pedestal inscribed with Greek lettering—I recognized it from Mikhail’s account of the pieces excavated from the Roman amphitheater. At a table next to ours, a family of three festivalgoers, trussed up in evening wear, were photographing the hotel. “It looks like something out of an Agatha Christie novel,” the daughter said in French, which seemed appropriate for a cast of characters who looked like they’d traipsed out of the Orient Express.

A hush fell over their table. “Inspired by the setting?” the father said, nodding to my notebook.

I explained that I was here for . . . “The nostalgia,” he said knowingly.

“The history,” I corrected. The defensiveness in my own voice surprised me. Inside my answer, I suspected, was some measure of superstition: the sense that if you gave too much of your love to the past, you risked not leaving enough for the future.

All this time, a smiling, doddering old man in a tuxedo had been ambling about, tending to guests and waiting on tables. He had been a steward of the Palmyra, he told us, adjusting his bow tie, for over half a century. He exuded a sense of total attention to detail, an unfaltering personal nobility, as if for all these years he’d remained the hotel’s rock of steadfast decency.

This was Abu Ali, the employee whom Leila had told us about. He and my father gleefully shook hands and began reminiscing. Abu Ali recalled his time working with Ahmed Kassab, the Palmyra’s longest-serving custodian, who died in 2019. They had taken the hotel from a staff of eight to forty during summers, back when the Palmyra had felt like the bright center of the world, hosting up to three hundred people for lunch alone. A few years ago, Abu Ali said, he and Ahmed had run into another member of the Alouf family who was on a pilgrimage to Baalbek, and had taken her to Room 27, whose walls were still adorned with whimsical drawings made by Cocteau. But my father was less interested in Room 27 and in Cocteau than in an old chicken coop and some bed skirts he thought he remembered. I was suddenly struck by something I had somehow overlooked: that in 1974, the last summer he spent in Baalbek, my father was only seven years old. The sunlit country he’d described to me, in other words, was one that he himself had just barely glimpsed before it disappeared—one that he, too, had imagined.

That evening, my father and I made our way from the Palmyra’s courtyard toward the ruins for the opening night of the Baalbeck International Festival. The quadrangle between the Temples of Jupiter and Bacchus had been filled with wooden tables and stalls selling wine and sfiha, a Bekaa specialty. I joined Joumana Atallah, a member of the festival’s executive committee; the festival’s president, Nayla de Freige; and other organizers in a booth between the Temples of Bacchus and Jupiter.

Joumana explained to me that the festival’s original intention was not only to promote Lebanon on a global stage, but also to orient its budding national character toward Europe, an effort for which the recognizable heritage of the Roman ruins offered the ideal venue. Much of the festival’s mission now, however, had to do with preservation. After the damaging or outright destruction of several UNESCO World Heritage Sites in neighboring Syria—in Damascus, Aleppo, and, well, Palmyra—the committee hoped that an annual international presence inside the ruins might keep the world’s eyes on Baalbek. (A few days later, Nayla would forward me a picture of Roberto Bolle, the Italian danseur étoile who was opening the festival, wearing a T-shirt listing his tour locations, with Baalbek lying securely between Trieste and Rome.)

Nayla and her colleagues listed, with a blend of pride and relief, the numerous ambassadors in attendance—from the Netherlands, Italy, the United States. They were interrupted only when an attendee, upon being handed a glass of wine, expressed her surprise that alcohol was being served here, in the Bekaa. A woman next to me laughed woundedly. “We’re not in Saida,” she said, referring to a public beach in southern Lebanon where a woman had recently been harassed for wearing a bathing suit. “Yet,” responded the attendee, raising her glass.

That night Bolle danced across the steps of the Temple of Bacchus to the roar of French-inflected bravos. There was an AI-is-coming number and an Earth-is-dying number, the first time since landing in Lebanon that I’d remembered the regular fears. At his performance’s climax, Bolle battled interminably with his own hands as though they were foreign bodies—a futile, unresolved struggle that ended only because the music did.

Throughout the evening, as dusk fell behind the temples, the starry dot of Venus traced a downward arc across the night sky. I tried to imagine what the atmosphere must have been like in 1956, when Leila’s cousin was putting on her green dress for Cocteau’s play. How safe Lebanon must have seemed, above so many layers of history; how distant from the rest of the country’s thwarted pan-Arab aspirations, or the political disaffection in the Bekaa, or all the nascent indicators of a land that would fall, some twenty years later, into the hands of wild young men with automatic rifles.

Somehow the site’s breathtaking antiquity had, all this time, succeeded in blinding me to its host country’s youth, its essential fragility. So, too, had Lebanon’s national anthem, played earlier in the night—that hymn of trumpets and horns, of brass-quintet grandeur and eternity, a diatonic, European hymn, with none of the anguished accidentals befitting the place Lebanon would turn out to be.

After the performance, my father and I stopped by the Palmyra’s balcony to consider the Temple of Jupiter, the view I had imagined so many times from Paris. “Do you know my grandmother never took us to see it?” he said. “Her father had made the ruins’ preservation his life’s work, but Teta Hélène herself never felt like going. She would always say, ‘Habibi, they won’t fly away.’ ” He laughed sadly. “It never occurred to her that we would be the ones to fly away.”

The following morning, my mother joined us in Baalbek. While my father delighted in watching children play soccer in the city’s parks, my mother made little attempt to hide her dislike of what Baalbek had become, frowning each time she saw a monument to a former militia or a Hezbollah fundraising urn. As we made our way to the ruins later in the day, my father tried to defuse the tension. “See?” He nudged her playfully, pointing out the lopsided banner hanging from a small, rundown shack: crépocrèpe. “It’s still here, our international Lebanon.” She did not laugh.

That night at the Palmyra, I asked my mother if she could introduce me to Rima el-Husseini, the manager whose husband owned the hotel. Rima had just finished showing the hotel’s guest book to a group of captivated tourists. When I explained that I was hoping to write about Baalbek, her eyes lit up. She wanted to talk about stories: Lebanon, she said, ran on them. “Always the golden age, always, ‘Oh, before, before . . . ’ But things change.” People ascribed much of the blame for the country’s downfall to Hezbollah, Rima said, but that “ignores the backwardness that existed for long before.”

In Lebanon, she contended, the past was either elegized or buried. People lamented the end of the golden age endlessly, but the war itself was still mentioned in political speeches and schoolbooks only as al-ahdas, “the events.” If you sat at the wrong end of a dinner table, you could still hear contradictory accounts of the events leading to the Beirut bus massacre that sparked the war. “Here people don’t care about history, they just—” Rima brushed an invisible object away. “No one names anything in this country. Like when someone gets cancer! Have you ever heard anyone use that word, ‘cancer’?”

The next morning, before my mother woke up, I tried—and failed—to find the slab that Leila said Mikhail had used to mark the entrance to the Roman amphitheater. Returning to the Palmyra after my search, I ran into Rima’s son, Hassan, whom I had seen running about the hotel the previous day with a watering can. I asked him if he knew anything about the mysterious slab, but he had never heard of it, so we ambled around the hotel’s grounds for a bit, and then climbed up to the roof to share a cigarette. Hassan was tall, with bushy eyebrows and a perpetual half smile. I was twenty-three and he was twenty-seven, and while we did not know each other, our stories were connected by this hotel, this city, where my grandfather was born and his family lived, and to which we had both been drawn, as if by some obscure spell. At Hassan’s feet was a trough filled with timid sprouts of lavender, sage, and thyme, which he planned on using to make tea for guests who, the following year, would not arrive.

Hassan looked up at the wall of solar panels that he and his mother had set up to provide the electricity the state rarely did, and ashed his cigarette, which seemed to be burning only from the sustained heat of the Bekaa sun. “Lebanon is the greenest country in the world,” he said with a bitter laugh. Then, stretching his arms toward the panels like a magician revealing an object transformed, he said: “Heliopolis.”

Throughout the rest of July, I made a few more trips back to Baalbek and attended more of the festival’s performances. My father and I brought our photographs of the Palmyra back to Leila, who shied away from them with a pained “yiii.” She inquired only after Abu Ali, and asked whether we had found the secret entrance to the amphitheater. When I said we hadn’t, and requested a more detailed description, Leila seemed confused. She had never seen it either, she clarified, and neither had my grandfather—they’d only heard about it in stories.

As for Lebanon, it, too, felt more elusive than ever. What was it, exactly—a sick child? A serial abuser? A myth? And could it ever become something else?

On our last day in Baalbek, I posed this last question directly to my father. He gave me a weak, encouraging smile. Lebanon was a place, he ventured, where at one point each of its three major religious groups had leaned on foreign influence in a bid to strong-arm the other two. “The Christians did it and failed, the Sunnis did it and failed,” he said. “Now the Shias are doing it.” I liked this hopeful summary—its implication being that Iran’s interference was also doomed to fail—even as I doubted whether it was geopolitics, rather than homesickness, undergirding my father’s faith in Lebanon’s inevitable recovery.

My mother, I knew, would have given a much different answer. And a week later, on August 4, as we stood at the Beirut port in the heat and languor of a protest, holding up our international fact-finding mission now signs, she did. Every year since 2020, the highway across from the port had flooded with hundreds of people marching with pictures of their dead loved ones, glimpses of particular griefs.

An old woman walked up to my mother and me. “Who was it for you?” she asked. She was clutching to her chest the picture of a young woman who I guessed was her daughter. My mother was taken aback. “Oh, no, sorry,” she replied. “Just the country.”

Last year, amid canceled flights, foreign embassies’ calls for evacuation, and the mounting threat of all-out war between Israel and Hezbollah, I nevertheless returned to Lebanon for the summer. The panic in the news contrasted with the Lebanese humor on the ground, a same-old-shit dissociation that I knew well. (As Israeli jets flew low over Beirut, breaking the sound barrier, the entire country gathered online to rate the sonic booms. “1/10: The sound of my husband’s fart is louder than today’s sonic boom,” read one entry.)

Then the Israeli bombardments began, and the laughter stopped. Thousands were killed in the span of a few weeks. Grainy snapshots of the Roman ruins, and occasionally also the Palmyra itself, appeared on social media as rockets landed a few hundred yards away from the Temple of Jupiter, sending up a massive cloud of smoke that dwarfed the six stone columns. As of this writing, Israel has issued an evacuation order for the whole of Baalbek, as well as two neighboring towns. One air strike reduced an Ottoman-era building across from the Palmyra to rubble, covering the first floor of the hotel in debris and blowing out the three windows overlooking the balcony. “It is so sad,” Joumana texted me. “We have sent an alert to UNESCO. Many people are mobilizing, but unfortunately Israel retains total impunity.”

I did not go back to Baalbek, where the festival was canceled and the Palmyra left empty. Instead, I wandered restlessly around the beaches with the usual expat crowds, venturing into the Mediterranean waters late at night. And, as I have done every year of my life, I returned to Paris when summer came to an end. On the flight, I considered my final drive back from the Palmyra Hotel the previous summer, when my father and I made a stop in Mreijat. It was his mother’s village, in Bekaa, where, in a house the family had also since sold, he had spent the other half of his blissful prewar summers. I was almost confused to hear Mreijat called by its real name, so often had my father used his nickname for it: “Combray,” in reference to Proust’s fictional town, a slow, childhood place.

By the entrance to the old family home, a man who sat tinkering with the wheels of a child’s blue bicycle spotted us drifting about outside and invited us in for coffee. My father waved me over excitedly. Bayti baytak—“my house is your house”—the man told my father, more fittingly than he realized. When my father explained that in fact the bayts really had been the same, the owner tried at length to persuade him to invest in a nearby property, hoping, it quickly became clear, to pad the village with an additional Christian family.

But my father did not want to invest in a nearby property. He wanted only to show me the stone-carved stairway inside the garden, where, as a child, he would race with his sister and all their cousins to hear a mysterious, invisible steam locomotive pass. Mreijat, the children later understood, had a station on the Beirut–Damascus railway, that pride of the Levant that made its first trip in 1895 and its last in 1976, one year into the war. Now all that remained of the once-majestic railroad were gutted stations and, in the few areas where militias had not scrapped the metal for weapons, rusty, overgrown fragments of track.

“Of course, we knew nothing of this at the time,” my father said. “All we knew was that a steam train passed at regular intervals, and if you climbed to the very top at the right moment”—he pointed to the long stairway’s final platform, which abutted a bare stone wall—“you could hear it choo-chooing in the distance.”

My father lingered by the steps, timidly climbing up the first two, then scaling the rest with unexpected verve. I followed him. The sun was scorching, and we had to pause a few times to catch our breath before we finally reached the top, where, winded and sweaty, we looked out ahead. But there was nothing much to see: only the bare wall and some gnarled shrubs.

We sat down wordlessly, the air completely quiet, the red roof of the house far below us. My father let out a soft laugh. The train was not coming, of course. He had missed it, by half a lifetime, by war and exile and a father and a sister.

This was where the story, or at least my story, ended: atop a stairway to an empty platform where an invisible train had already passed. A small story, not so much at history’s vanishing point as already beyond it. My father and I stayed a long time together atop those stairs. Did part of me think that if we waited long enough, the train would actually come, that we would somehow hear it trundling past us in perfect four-count measures? Of course not. But then again . . .