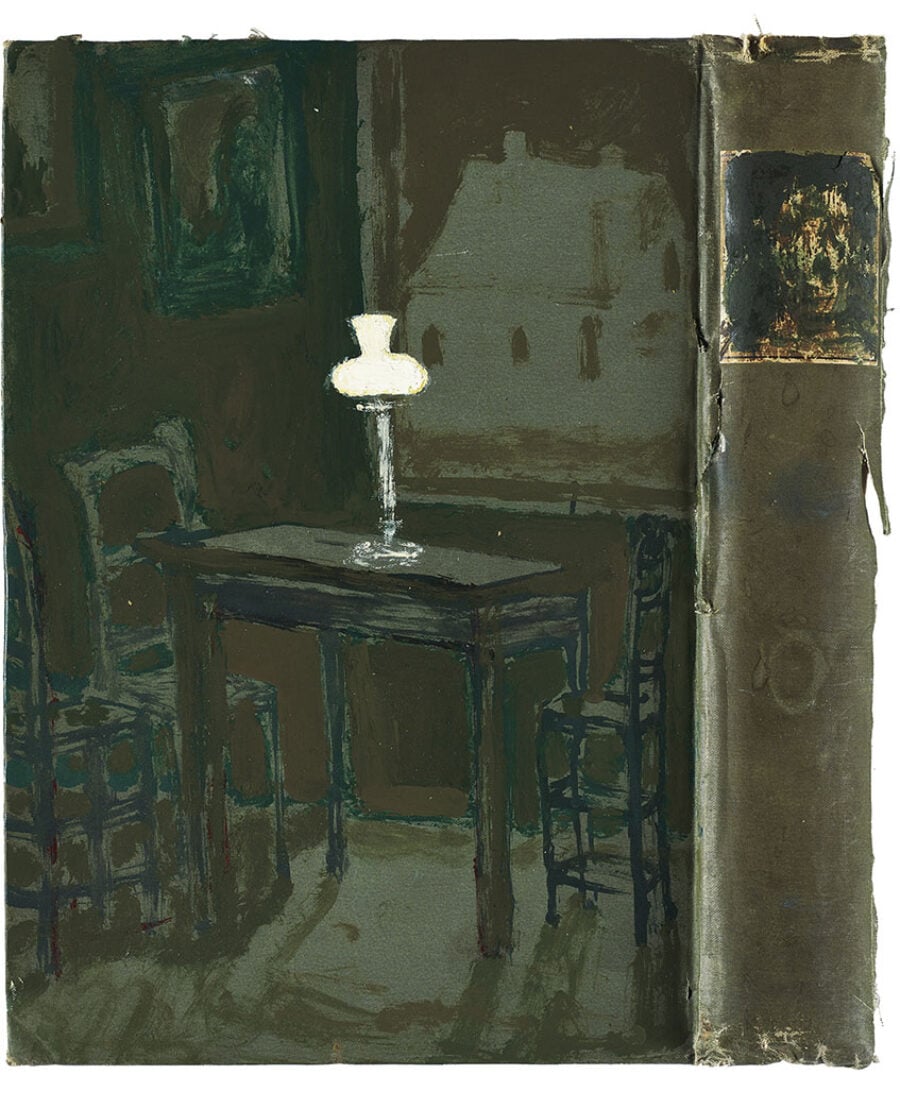

The one light we keep on, a mixed-media artwork (enamel and oil on a hardback book cover) by Andrew Cranston. Courtesy the artist and Ingleby, Edinburgh, Scotland

Mother-Daughter Story

How to explain to her daughter.

Back when she was in college, she had taken a literary seminar for which she’d had to read Kafka’s “Letter to His Father.” After the class had discussed it, the teacher gave them an assignment: write a letter to one of your own parents. Moans and groans, the loudest of which probably had come from her. It was the kind of assignment she hated. She hated writing prompts in general. If she had to write something, let her choose what about. And the Kafka—well, she hadn’t known what to make of it.

“It was weird, but not in a good way. You think that because it starts out ‘Dearest Father’ it’s going to be loving, but in fact it’s just one long rant.”

The teacher had laughed and said, “I’m not suggesting you actually send your letter.”

Kafka hadn’t exactly done that either, though it seems he’d wanted his father to read it. He gave the nearly fifty-page typed manuscript to his mother and asked her to pass it on. Did he know, deep down, that she never would? More than three decades later, and against Kafka’s own will—thanks to his literary executor’s decision to disregard Kafka’s instructions to burn all his papers, unread, after his death—it would be shared with the world. By then Kafka’s father and mother were dead.

There was speculation that the letter was in fact not an actual letter but a story.

“You mean like autofiction,” said her daughter.

“Yes. Except that autofiction hadn’t been invented yet.”

She remembered that the teacher had asked the class to reflect on the decision of Kafka’s literary executor and close friend, Max Brod, not only not to destroy Kafka’s writing but to arrange to have much of it published. She was the only one to believe that what Brod had done was wrong.

“ ‘But think what the world would have lost!’ ” she said, mimicking falsetto voices (the class—the whole college—had been all women).

Life would have gone on! The world would have survived! Granted, without one of its most enduringly useful adjectives.

“So, you would have burned everything,” the teacher had said, sadly scandalized.

“If I believed that’s what my friend really wanted,” she replied, burning in the hot seat herself. Which Brod always claimed that Kafka really had not. Even so, wouldn’t he have drawn a distinction between the publication of his novels and stories and that of his private letters and diaries?

“What if everyone behaved that way toward the dead? What would be the point of anyone ever making out a will, or informing loved ones of their final wishes? What makes literary genius an exception?”

The morality of it eluded her.

“To them, I was like the Taliban blowing up those ancient stone Buddhas,” she said, anachronistically.

“And do you still feel the same?” her daughter asked.

“I do. Though now I would never argue with anyone about it.” It had come with age: caring less and less what other people thought.

When her daughter was born, she had named her Anaïs. Not after the writer, but simply because she thought the name was beautiful. Her daughter had other feelings about it. First, there was the constant annoyance of mispronunciations, including the inevitable (and deliberate) “Anus.” In fourth grade, someone wrote on the whiteboard anaïs? no , anaïsn’t, starting a running joke that dogged her for the rest of the school year. Later: Did your parents name you after that perfume? (She had sniffed it once in a Macy’s and nearly gagged.) By middle school, she had dropped the mark over the ï. Once she was old enough to read Anaïs Nin, she was mortified. Not because of the erotica—she was no prude—but because of the woman’s insufferable narcissistic personality, her droning and pretentious prose.

She became Ana for a while until, after reading Little Women for the first time, she adopted, for keeps, Jo.

Her mother understood. She had never liked the name her parents gave her, either, preferring her nickname, Mo.

Her husband referred to them together as MoJo.

They found the letter in the drawer of Mo’s mother’s nightstand, along with a bottle of Tylenol long past its expiration date and a tube of ChapStick.

Jo said, “You must have sent it to her.”

“I did not,” said Mo. “No way I would’ve done that. And if I had, believe me, I’d remember.”

She vividly remembered banging out the manuscript on her aqua-blue Smith Corona manual typewriter, all in one frenzied go, on Dexedrine. Now it was an antique (Jo called it a fossil), the onionskin paper yellowed, the Wite-Out that had been used, in some spots thickly, to cover up mistakes, flaking. The staple holding the flimsy pages together had rusted, and the comments written by the teacher in pencil were too smudged or faded to be legible.

Jo asked her mother what the teacher had said.

Mo laughed. “She sent me to the school shrink.”

Just once had she been to see that dwarfish, bearded old man, comical in his enormous chair, his enormous desk between them, his nose almost touching the legal pad on which he scribbled throughout the session. Known among the students as Pocket Freud.

It was a shock to learn that he had not read Mo’s letter.

“I remember that he never said a word. I was completely ignorant about therapy. The last thing I was expecting was neutrality. I thought I was going to be comforted, that’s how naïve I was. I didn’t know that’s not how it worked. Anyway, that was the end of it. He didn’t ask me to come back. The teacher never said anything to me, either, and no one ever mentioned the letter again.”

But some years later, despondent after being rejected by a man she adored, she’d let a friend talk her into joining a writing group: four other women and two men who’d met earlier as members of a book club. One of the men taught in a university writing program. When some in the group were having trouble coming up with story ideas, he shared a list of prompts that he’d been given as a student and that he sometimes used in his own classes.

And there it was again: “You asked me recently why I maintain that I am afraid of you.” The first sentence of Kafka’s letter to his father. Write a story starting with this sentence, went the prompt. When you’ve finished the story, delete the sentence.

The story did not have to be in the form of a letter, and “you” could be anyone at all. But Mo wanted to write again about her mother—a mother-daughter story like those that seemed to be so popular.

Now she reread Kafka’s letter, and this time she did not find it boring. A parent who made a child feel fearful and worthless; childhood not as a carefree, innocent time, but as a test of endurance. She could relate to that.

Again with the encouragement of the friend who’d brought her into the group, and who now insisted that Mo’s mother-daughter story was good enough to be published, she began sending it out to journals. She respectfully obeyed the editors’ rule of no simultaneous submissions, and she always included an SASE. By the time the last rejection note arrived—well over a year after the submission—the sight of her own handwriting on the manila envelope momentarily baffled her: she had forgotten all about the story.

She had also left the group. While her story had been making the rounds, she’d managed only a string of false starts and had struggled to hide her lack of interest in the others’ writing.

Sometime before the onset of her last illness, Mo’s mother had listened to an audiobook about Swedish death cleaning and had taken to heart its advice: declutter your home as much as possible to spare others the trouble once you’ve passed on. For this Mo was grateful. She knew people who’d had to deal for weeks and months with that particular chore. It helped that her mother had already downsized to a cottage in the same Long Island town where she’d lived from the time of her marriage to Mo’s father, who’d died when Mo was eight. The marriage had been sufficiently unhappy—mostly because of his alcoholism, which was also to blame for cutting short his life—for her mother not to want to chance it again.

Mo’s own marriage had been only slightly less awful—another heavy drinker, Hugh was also a serial cheater—but they’d managed to stay together until Jo was on her own. Though it was not to be, in anticipation of having a second child they had moved, after Jo was born, from New York to Philadelphia, where the cost of living was lower, and where the consulting firm for which Hugh worked had a branch and was willing to transfer him.

Mo worked as an ER nurse until, one day in her forties, a misstep sent her somersaulting down a flight of stairs like a stuntman. She had back surgery and spent half a year recuperating, but she was never up to the physical demands of nursing again. She took a job supervising a large medical office—as stressful though not as exciting as the ER, thanks to the harrowing bureaucracy of the health-care system—from which she could not wait to retire.

Jo lived in Chicago, where she’d attended grad school with some dream of becoming a psychologist but ended up marrying the owner of an Italian restaurant that had been in his family for three generations and which then became hers as well. The restaurant had barely survived the pandemic lockdown and had been struggling ever since. When Mo saw that they’d raised the prices so that even a bowl of pasta with red sauce cost more than twenty dollars, she said, “Well, there’s your problem right there. Who can afford it?”

Jo explained that their prices were not the problem, that it was the restaurant’s rising expenses that were the problem, and in fact the restaurant was packed every night.

“And we don’t call it red sauce,” she said.

“Oh, excuse me,” said Mo.

“I didn’t mean it like that.” Jo had slipped. Usually she was more careful around her mother. She had learned long ago that a person who was much criticized as a child grows up to be not hardened or immune but, rather, hypersensitive. Even mild criticism, even if it was undeniably justified, caused her mother to overreact, becoming defensive and sullen. Many a fine day had been spoiled in just this manner.

Whenever Jo was frustrated by Mo’s behavior, she reminded herself that Mo really had suffered at the hands of her own mother. “Every single day, every little thing, wrong wrong wrong, bad bad bad.” She had even tried to blame her husband’s troubles on little Mo and her two brothers. “What man wants to come home to a house full of whiny, dirty brats?” she’d snap at them. “No wonder Daddy drinks.” If they’d been rich, she would have shipped them all off to boarding school.

Something Jo had learned in psychology: when a person has had a bad parent, the person remains that parent’s child all their life.

Jo had flown to Philadelphia on a Friday, and she and Mo drove to Long Island early the next morning. Passing through her hometown, Mo pointed out how much had changed over the gentrifying years, with less than a handful of the old mom-and-pop places surviving among the chic new ones.

“What’s that for?” Jo asked about a long line of people on one street. As they went by they saw that it was for a patisserie—specifically, for the crookies that were sold there, according to a signboard out front.

“Oh, I heard about those,” said Mo. “You have to line up early to buy one, because they sell out right away. You can get them in Philadelphia now too.”

“And in Chicago,” said Jo.

“They must be so good,” said Mo, hungrily. But Jo said, “It’s not about the taste, Mom, it’s about the hype. People always want whatever the latest viral food trend is.” Which she thought was ridiculous. But Mo, who had a history of stress-eating and a constant craving for comfort foods, was empathetic. In her office she’d once heard a patient who’d been sternly warned by the doctor to lose weight protest: “But food is the only sex I have.”

Mo had estimated that it wouldn’t take more than a weekend to sort through her mother’s things. Another reason to be grateful: there’d be no need to deal with the house itself, which was a rental. Over the years, Mo’s mother had become friendly with her landlord, who lived nearby, and she had agreed to leave him the cottage’s furniture. Before going into hospice, she had arranged for someone from a local donation center to pick up the dozen boxes of clothes and housewares now stacked and waiting in the hall. They were scheduled to come that Monday.

Jo said, “Grandma really thought of everything, didn’t she.”

There was not much that Mo needed or wanted for herself, but she picked out a few mementos, mostly photographs and pieces of jewelry, and a pair of Art Deco lamps that had been one of her parents’ wedding gifts—nothing that wouldn’t fit in the car.

Neither of Mo’s brothers had volunteered to help, being the kind of men who viewed this sort of task as women’s work.

“They’d only be in the way,” Mo said. “They’d only slow us down.”

Her brothers had considered everything else having to do with their mother’s illness and dying also to be women’s work. But at least they had shown up for the end.

Mo forgave the boys, as she always referred to them, because she understood how complicated grief was in a family like theirs. The anguish of mourning not just the death of a parent but a parent’s love that never was.

From being hypercritical of her children their mother had moved on, once they were grown, to indifference. With every year, she became less and less informed about their lives. Some years she might send a birthday card, other years not. The arrival of grandchildren changed nothing. If anyone had asked her anything beyond their names and ages, she could not have said much. Her detached manner at family gatherings suggested that she’d just as soon have been somewhere else.

Mo never understood how her mother survived the isolation. She had a few acquaintances, and she got along well with her neighbors, but she had nothing like a bosom friend. She did not even have a pet. (She was afraid of dogs and superstitious about cats.) She had a hobby—gardening—and she had her favorite TV shows, and the audiobooks that she borrowed from the library. She was a regular churchgoer, her reverence for priests surpassed only by her reverence for the pope, and when her youngest had screwed up his courage to tell her he was gay, she’d let Father Gaffney guide her. Her son was a sinner; it would be sinful to condone or accept who he was. Just as she’d thought.

During the lockdown, she had taken up backyard birding. While she was in the hospital, when Mo went to collect some things for her from her house, she’d noticed a complaining racket at the empty feeder. And for the first time since she’d learned of her mother’s diagnosis, she had wept, thinking that, more than any human, the birds would miss her.

In midlife had come a time when thoughts of her mother ceased to torment Mo. She had her work, a husband and child, no shortage of friends, hobbies of her own. But, getting older, she often found herself jarred by flashbacks or brooding about the past.

On Mother’s Day, a radio host invited call-ins: “Tell us about your mom, how you like to remember her, what was special about her.” Mo wondered for how many listeners those words would mean the opening of a wound. She remembered what a convicted criminal was once reported to have told a judge: “My mother taught me that there was no such thing as mercy.”

Not that she thought there was any such thing as a perfect family, of course. But the world was full of examples of what was held to be not some high ideal but the norm: parents who loved their kids, who protected them, who wanted them to be happy. And, futile though she knew it to be, resentment at having been deprived of this—what to call it? was it a right? not a privilege, surely?—threaded her days.

“I’ve always felt like the hungry, penniless kid with her nose pressed against the bakery window,” she said.

It was called luck, of course. She had been unlucky in her parents. But the luck of being born into love shouldn’t be like the luck of being born into money, should it?

She could not recall a single instance when her mother had shown guilt for something she’d said or done. The guilt was all on Mo’s side, a sense of unworthiness and self-horror that was like a kind of dirt that couldn’t be washed off. Like the shame that Kafka said he was afraid would outlive him. Out of shame, young Mo had traded the truth about her background for a book of lies. A college friend who saw through it all had once accused her of being emotionally disturbed; she needed to get help, the friend said. (But who to turn to? Father Gaffney? Pocket Freud?)

It was this mire of shame and humiliation and denial that she believed helped explain why she and her brothers had failed to bond. As if escaping the pain of the past had somehow required escaping one another. And the last thing either of the boys ever wanted to do was talk about it: that would have meant reliving it.

She didn’t get to choose her parents. But why later, given a choice, was she driven to choose badly, drawn time and again to men whose rough childhoods matched her own, only to discover how inauspicious this was for a couple? It was only in hindsight that she saw clearly that her and Hugh’s hope of turning two dark pasts into one bright future had been doomed from the start.

Yet the most wonderful blessing had come of it. Through the years, she and Jo had thrived together. They were as devoted as any mother and child. They were each other’s best friend. They were MoJo! (Once, when Hugh had tried to excuse his infidelities by saying that it sometimes seemed as if the two of them had no need for anyone else, and that he felt left out, Mo was outraged. But later she saw that the assertion contained a kernel of truth.)

There had been a time, however, when the relationship had been seriously tested. Jo was just twenty then and dating a man ten years older: the owner of a tattoo parlor.

It had always amazed Mo how tattoos had come to be so common. People who’d never expect to wear the same wardrobe or hairstyle for life: How could they think they’d want to be stuck forever with the same tattoos, let alone the flamboyantly gaudy or lurid ones that were now ubiquitous?

She remembered reading an article about people’s tendency to be shortsighted even in matters of major importance, from retirement plans to climate change. According to studies, the human brain was very bad at grasping the reality of the future. Most people could not imagine, let alone worry about, their own future selves, because those selves were like strangers to them.

Well, if any were needed, thought Mo, tattoos were it: proof of humans’ devil-may-care nature and why our world had come to be in the sorry state that it was.

During the years Jo and her boyfriend were together, every time Mo saw her daughter, another patch of skin had been sacrificed. (The man himself was as tattooed as a Russian gangster.) How could Jo say that he was only making her more and more beautiful? What did Mo care that some committee had named him one of his city’s top ten tattoo artists? To her, he was not an artist; he was a vandal.

And what about the risks? She was not just a pearl-clutching boomer; she was a nurse. Even if there wasn’t indisputable evidence of a link between tattoos and cancer, at least some inks were known to contain carcinogens. And how could a person with all that inked skin catch the kind of small change in pigmentation that was a sign of melanoma?

Though as dismayed about the situation as Mo, Hugh was no help. “I say we kidnap the bastard and strap him down and tattoo dickhead across his face.”

Then Mo made a bad miscalculation. She would call Jo’s boyfriend and try to talk to him about her concerns. His flippant attitude (“He must have said ‘whatever’ ten times,” she reported later) had incensed her. When Jo learned what Mo had done, it was her turn to be incensed. Though they did not suffer a complete break, Jo decided that what mother and daughter needed was a lot more distance between them.

It gave Mo no satisfaction to know that she was right, that there would come a day when Jo would regret how she looked.

The tattoo artist was not an addict, but he was a user, and one night when he was alone in his shop he accidentally overdosed.

Witnessing her daughter’s prostration, Mo understood something she hadn’t fully acknowledged before: how deeply Jo cared, how much this man had meant to her. Mo herself had not yet experienced such a terrifying, disabling grief. It rendered Jo an invalid. There were days when, if she didn’t want her child to starve, Mo had to spoon-feed her.

“Only you could have gotten me through it,” said Jo, when she was finally able to move on.

Jo said, “Well, if you didn’t send it to her, how did it get here?”

When Mo’s mother was moving from her old house to the cottage, she had called Mo to say that she’d come across a box of stuff from Mo’s college days, some old course notebooks and term papers. Did she want them, or was it okay to throw them out?

“I told her to throw them out,” said Mo. “It didn’t occur to me that she might look through them—she’d never shown any interest in what I was studying in college—and if she did, why would I care? I never even thought about the letter being there. Think how many decades it’s been.” Could it have been a subconscious act, leaving the letter where her mother might one day find it? was a thought Jo kept to herself.

“And she never said anything to you,” said Jo.

No, she had never said anything. She had gotten rid of everything else in the box, but this one thing she had saved. And placed it there, in her nightstand drawer, so that Mo could not miss it: her love letter.

Dearest Mother, I have always believed, and I still believe, that if you would only let me I could make you happy.

“She was old,” said Jo. “She was sick, and she was on all those medications. She must have been confused.”

Mo said, “Don’t you dare make excuses for her.”

Jo was wondering whether to ask if she could read the letter when she saw that her mother’s face had turned blotchy. Her mouth was twitching, and she was breathing so hard that she was grunting. She began tearing up the pages, her hands working furiously, sending scraps of paper flying into the air.

After Mo had left the room, Jo swept up the pieces and dumped them in the trash.

For the rest of the day they worked mostly in silence, urgently and so efficiently that they managed almost to finish the job. By then it was dark. They ate the rotisserie chicken and potato salad they’d bought on the way in from town, discussed whether to watch a movie, agreed that they were too tired, and went to bed.

On the phone with her husband, Jo confessed that she’d been relieved when her mother tore up the letter. “I was afraid to read it,” she said. “I mean, afraid I wouldn’t know what to say.”

She was alarmed to hear her young son’s voice in the background. “At this hour?” she said.

“I know,” said her husband. “But he’s not being very cooperative. He wants you home.”

“I want me home, too,” said Jo. After only a day she felt as if she’d been gone for a week.

She was trying not to dwell on the fact that, since Mo had picked her up at the airport, not once had she asked after her son-in-law or her grandson.

Mo woke up the next morning to a delicious smell. Jo was already up and busy in the kitchen, making coffee. The smell was coming from the toaster oven. Mo peered through the glass and gasped. “You got crookies!”

Jo said, “I was just keeping them warm.”

They ate breakfast on the front porch, ignoring the damp that the sun was as yet too weak to evaporate from the wicker furniture. Hope had not died among the birds: back and back they came to the feeder hanging empty from a tree branch.

“This reminds me of a story,” said Jo. “A famous Carver story.”

Mo said, “Which Kafka story?”

“Not Kafka. Carver.”

Jo had noticed that, since their last visit, at Christmas, her mother had developed some hearing loss. She’d already decided that, before flying home, she would say something to her. She’d have to be delicate about it, though, so that Mo wouldn’t react defensively.

“Raymond Carver,” Jo said. “Remember him? I can’t think of the title.”

The grief of a couple whose little boy has just died is interrupted by nasty anonymous phone calls, which turn out to be from the baker to whom they owe money for the birthday cake they had ordered for the dead child but had never picked up. When the couple goes to his store to confront him, the mortified baker apologizes and offers them coffee and cinnamon rolls hot out of the oven.

Jo said, “He urges them to eat, because when you’re in pain, he says, eating can be a comfort.”

“Hmm,” said Mo, nodding emphatically with her mouth full.

“ ‘A Small, Good Thing.’ ”

“Hmm?”

“That’s what the story is called. I just remembered. The baker calls eating in a time of trouble a small, good thing.”

“Well, I wouldn’t call these small,” said Mo. “But didn’t I say how good they’d be?”

Early though it had been when Jo took the car into town, there was already a line outside the patisserie for the crookies—no surprise on a Sunday morning. She had no intention of joining it, but she went inside and bought two fresh-baked croissants and one large, soft chocolate chip cookie. Back at the house, she sliced open each croissant, placed a piece of the cookie inside, and another piece on top, and she heated the croissants in the toaster oven to melt everything together.

Mo said, “This is the best pastry I ever had.”

Maybe once they were on the road, their grim task done, Grandma’s house receding farther and farther behind—maybe then Jo would tell Mo the truth, and they could laugh about it. She liked to think that, whenever her mother thought back to this time, its bitterness might be countered by the memory of something funny, something warm and sweet, a reminder that in her grief she had been comforted, and that she was loved.