Julian the Apostate, by Julien Nguyen © Julien Nguyen. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Shia LaBeouf and I were born six days apart in June 1986. I see him as the representative of my nanodemographic—as if my week’s cohort of white American males emerged from a brief huddle to announce, “This is our guy.” Our guy turned out to be a middling actor who once walked the red carpet at the Berlin Film Festival with a paper bag over his head. Harrison Ford has called him a “fucking idiot,” his ex has sued him for abuse, and he’s been arrested, drunk, at a Walgreens and at a Broadway production of Cabaret, among other venues. Child stars often lead difficult lives, but something in LaBeouf’s self-regard and disenchantment feels generational. I picture the two of us weaned on the same media diet, digesting images in unison—Nancy Kerrigan in tears, O. J.’s slow-speed chase, the Taco Bell chihuahua—and I think, there but for the grace of God go I. After 9/11, LaBeouf, then fifteen, recited a poem for a segment on the Disney Channel. “Through this pain I’ve learned a powerful lesson,” he said, flanked by the Stars and Stripes. “It’s awesome to be an American citizen.” By 2009, he was telling Parade, “Sometimes I feel I’m living a meaningless life, and I get frightened.”

This was white suburban adolescence in the Aughts, when love of country boiled down to love of Disney. The president told us to fight terrorism by vacationing in Orlando. We listened voluntarily, even ecstatically, to songs that the CIA soon used to torture prisoners at Guantánamo. We collected Pokémon cards and sneaked into theaters to see American Pie 2. We wore purity rings, ate freedom fries, and perfected the use of “gay” as a derisive epithet. After it was over, we plowed our resources into the nostalgia industry to ensure that we could spend the rest of our lives blithely misremembering it. I’m happy to see low-rise jeans again, but I’ve lost all sense of where they really came from. When I look over my shoulder, I see a pyre, still blazing, of Incubus CDs, inflatable furniture, and back issues of Maxim.

At the time, 9/11 was heralded as the end of an era, but Colette Shade, in Y2K: How the 2000s Became Everything (Dey Street Books, $29.99), contends that it was the middle of one. Her Y2K is an ugly unbosoming of an American dream that began with the dot-com boom in the mid-Nineties and ended with the subprime-mortgage crisis in 2008. In these years, she writes, “we became meaner, stupider, more violent, more conformist, more childish, more materialistic, more racist, and more vindictive”—all with the stick-to-it-iveness that’s gotten us where we are today. Y2K comprises ten essays on bugbears from the Aughts, including bling, Girls Gone Wild, gas-guzzling SUVs, McMansions, malnourished post-Soviet runway models, Britney’s shaved head, WMDs, the Patriot Act, and Starbucks’ unseemly expansion. The decade gave many of our most persistent character defects (phone addiction, complacency about genocide) a shot in the arm.

Y2K retrospection is fairly new, but already there are rules. You must invoke Francis Fukuyama. You must describe the paranormal bleat of a dial-up modem and deploy “cyber” as an adjective. Mention how designers made everything look like bubbles, as though aestheticizing the economy’s irrational exuberance. Shade gets this boilerplate out of the way early, fortunately, and then she’s on to more prurient fare—prurience being one of the Aughts’ dominant modes and a skeleton key to its real history. Google invented its Image Search to accommodate interest in a revealing dress that Jennifer Lopez wore to the Grammy Awards. Paris Hilton’s 2004 sex tape, 1 Night in Paris, opened with a dedication: “In memory of 9/11/2001 . . . We will never forget.” Boys tricked their friends into visiting shock sites like goatse.cx, which displayed an image of a naked man bent over and spreading his cheeks: how interesting that we were all so into sending and receiving this. The homophobia and misogyny in those years came at you like a battering ram. After Heath Ledger overdosed, in 2008, Perez Hilton—a blogger known for drawing rudimentary dicks and cum drops over unflattering celebrity photos—sold T-shirts with the slogan why couldn’t it be britney?

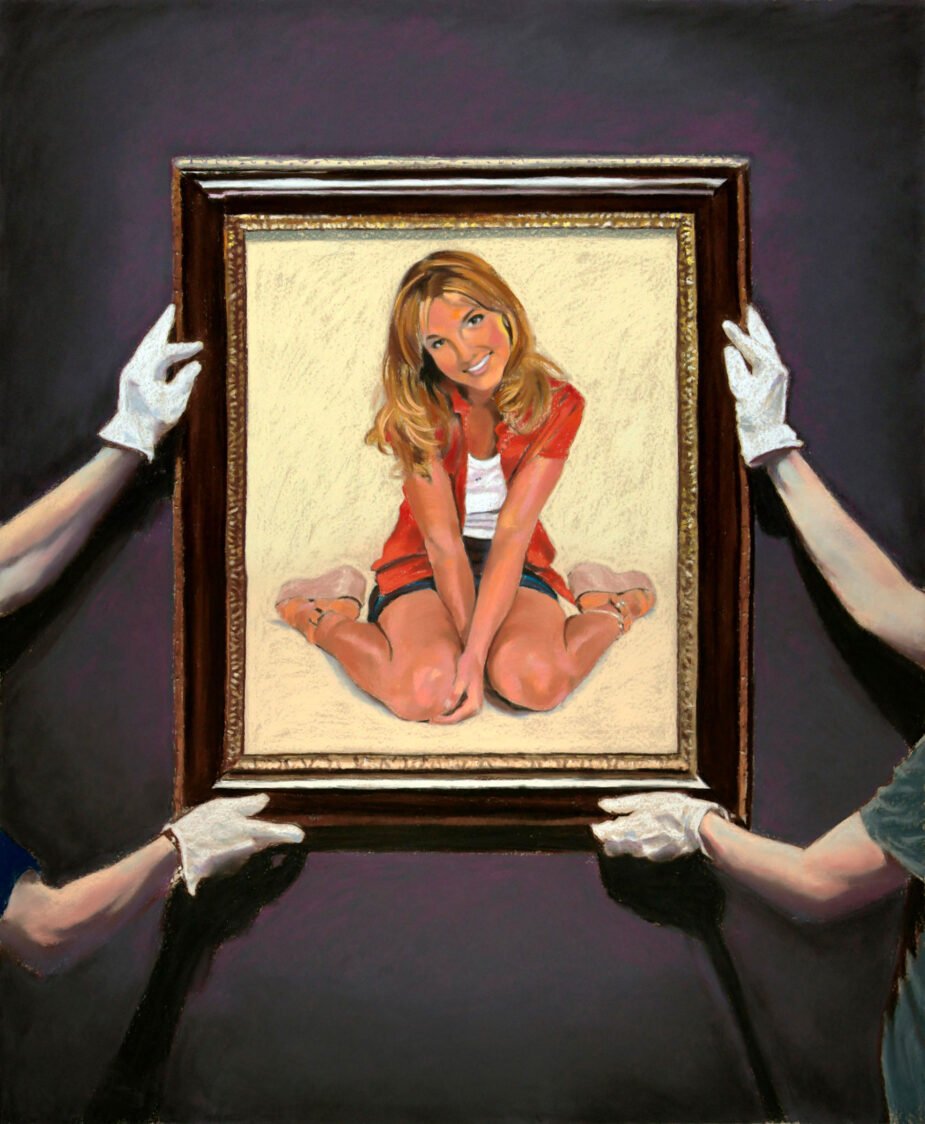

White G(love)s, by Eric Yahnker. Courtesy The Hole

Shade was a fellow teenager during most of this, which makes us both irrefragable authorities. Teens, she notes, were Y2K’s most coveted commodity and its most abundant. There were a record thirty million or so of us imbibing a consumerist ethic as smooth and cold as a domestic lager. She’s excellent on the long-term effects of existing in order to want—how emotion and self-discovery were channeled through consumption. I can remember feeling as she did about, say, her mom’s new car (“When I saw other late-model vehicles on the road I felt like we were part of a club together, just like I did when I went to the mall”) and her family’s home kitchen renovation (“I noticed that the people on TV also had our kind of countertops”).

Market research grew so specialized that, by 2001, a communications professor could say without exaggeration that corporations were “colonizing” teens’ minds “like Africa.” They wanted our flesh, too. The July 2003 cover of Vanity Fair read it’s totally raining teens! Among the nine girls depicted were Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen (also born in June ’86), whose eighteenth birthday was feverishly anticipated in the press. The pervs of every generation have fetishized the young, but with the Olsens the tone became teasingly worshipful; having been stars since infancy, they were thought to be media-savvy enough to take it in stride. They “sound like ancient souls in nymphet bodies,” Vanity Fair reported. “They seem to siphon their belief in themselves from a limpid pool.”

That pool may have been their only source of calories. Few adults then noticed, or cared, that many of these manicured, well-rehearsed, overachieving girls had quietly developed eating disorders. Shade writes movingly about her own efforts to starve herself, the shame of her obsessive discipline. For most boys, of course, self-control was never a consideration. Our insecurities took stupider forms. I remember a rumor that Yellow 5, the food dye used in Mountain Dew, lowered your sperm count. Then it was cell phones: cell phones lowered your sperm count. No one suggested that the answer was to deny yourself a soda or a Motorola Razr. The answer was to have more sperm.

More sperm? Try Edmund White’s The Loves of My Life: A Sex Memoir (Bloomsbury, $27.99), a veritable flash flood of semen, commemorating his encounters with dozens of men. White once estimated he’d had three thousand partners—“Why so few?” a contemporary asked—and his prose here, as ever, is so redoubtably stylish that I almost wish he’d enshrined every last tryst in print. What he has gotten down are the wisdom, fun, churlishness, humor, vanity, despair, agony, elevation, debasement, discovery, and delight, along with the bad breath, the body odor, the crabs, and the English Leather liberally applied. Above all, the beauty. White turns eighty-five this month, and he’s been a “practicing gay” since thirteen, so his story doubles as a history of gay America: “We were just sliding out of the era of heavy-drinking Tallulah impersonators into the pot-smoking Village People period of the weight-lifting, hypermasculine clone.”

I knew whenever White began a thought with “in those days”—a spritz of mist to which only octogenarians are entitled—that I was in for a treat: “In those days gay couples had dogs, not yet children.” “In those days we didn’t have pornographic movies to imitate. We needed an actual instructor.” And on urolagnia, “a frequent practice in those days”:

I can remember picking up someone with a yellow handkerchief in the back left pocket of his jeans, indicative of his desires and practices, buying a six-pack, and going into a quiet empty warehouse and recycling our beer for a happy, infantile hour. The beer was warmer, more fragrant, when drunk directly from the tap of my date’s microbrewery.

Clearly this is not a book for prudes. An anecdote about “an entire football” (American or Euro, I cannot say) used at “a fisting colony in Normandy” had me clutching my pearls. On the whole, though, White respects carnality too much to profane it. He can describe an episode of defecation in a two-car garage as if it were the plainest, tenderest thing, a chaste kiss. “Real erotic writing,” he believes,

is sensual without being sentimental, unpredictable, startling, an odd mixture of femininity and masculinity, the spiritual and the human, and frequently funny, especially when the body fails the imagination.

His own writing is this way, though the body never fails his imagination. Whenever someone unfurls a thick one from his jeans—every other page, basically—White finds the words for it: “Big, ropy . . . like an upside-down caduceus, where the snakes were veins, the wings were balls.” “A dick as big as a child’s arm and a bespectacled sweet face like Schubert’s.” “His dick was large as something that would have saved the lives of three Titanic passengers. It looked segmented only because no one could perceive something so long as unified.”

Twinned, by Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy Semiose, Paris

I could go on, but I shouldn’t suggest that the book is an endless romp. White spent years in therapy trying to straighten himself out. His life exhausted him. He’s well aware that it’s almost over, with all the valediction that entails. “Now in the cold polar heart of old age I look at all my travails in love as comical and pointless, repetitious and dishonorable,” he writes. He mentions AIDS often, ruefully but always passingly, because he’s here for the sex: this is what mattered most for him, and this is what he can transmit in high fidelity. I’ve seen sex written about with passion and dispassion, but seldom in the same book, and never in the same sentence. Maybe everyone in their eighties should write candidly, fearlessly, about what they did and wanted to do in bed or in the steam room or with twenty men in an empty truck on Christopher Street, and their stories should form the fundament (as in, the buttocks, not the foundation) of sex ed. But really what I want is for White to have access to everyone’s memories, their spank banks, with full creative license.

He notes accurately that “straights are reluctant to write about gays”—we don’t want gays telling us how wrong we’ve gotten them, and we don’t want to seem gay. Putting aside my sense of trespass, then, the highest praise I can pay this book is that it made me wish I were gay. (And yes, I felt this in the asinine, half-blind, touristic way that Y2K-era white boys flashed gang signs and rapped along to Clipse—in other words, as we said at the time, no homo.) Not just for the adventure and the abandon, but for the similes. A straight writer could never land two about linen in the same book. “His complexion was faultless and glowing, as if a light were shining through the best Belgian linen,” White writes, and later: “sweet lips, as soft as frequently washed linen.” Line for line, I can’t recall the last time I enjoyed reading anything so much.

“Is sex the desperate, passionate thing it was in the past?” White wonders. “Do young people fast, weep, threaten suicide, as they once did until they knew if their love was returned or if they would get dumped?” Reading Antonio Di Benedetto’s The Suicides (New York Review Books, $16.95), published in Argentina in 1969 and now translated from the Spanish by Esther Allen, it seemed to me that suicide is no longer the desperate, passionate thing it was when this novel first came out. In those days (I’ll allow myself the phrase just this once), it still had an existentialist voltage. Now it’s a contagion, a public-health concern.

Di Benedetto’s unnamed narrator is an Argentine reporter in his early thirties tasked with identifying two people who have killed themselves. They’ve been photographed in death, but there’s no saying who the photographer is, and in both cases their eyes register pure terror while their mouths are “grimacing in somber pleasure.” Our reporter is obsessed with squaring this seeming contradiction. Maybe it’s because his own father killed himself, or because autoerotic asphyxiation wasn’t so well known then. He pursues the story lackadaisically, preferring to see movies alone, behave oafishly with women, and appear generally on the verge of disintegration.

“Approximately 17 of 41 Sperm Whales Which Beached and Subsequently Died, Florence, Oregon, 1979,” a vintage chromogenic print by Joel Sternfeld © The artist. Courtesy the artist/Rago/Wright/LAMA. Collection of Susan and G. Ray Hawkins

On this last count, he’s much like the heroes of Di Benedetto’s Zama and The Silentiary, with which The Suicides forms a de facto trilogy. I loved Zama—about a frustrated, lascivious bureaucrat stuck in an eighteenth-century colonial backwater—but The Suicides trades its comical grandiosity for noirish brevity, with mixed results. It works when the reporter and his photographer colleague, Marcela, are chasing down the details of a suicide pact in the dusty, sun-streaked hills. And it works when the reporter is entertaining his usual death-obsessed thought spirals: “Am I a normal man? I don’t make much noise. I like many things. I live my life. I wonder why we’re alive.” (LaBeouf: “Sometimes I feel I’m living a meaningless life . . . ”)

But a good chunk of the novel amounts to fun facts about suicide. Another colleague routinely barrages the reporter with memos and data about the nature and history of self-harm: “Highest national rate: East Germany, average of 28 suicides per 100,000 inhabitants.” “More than a hundred whales committed suicide by hurling themselves one after the other onto the beach last Thursday.” Whatever shock these statements once had has dissipated; it’s no longer bizarre to grasp suicide as a litany of statistics. They reminded me of the Museum of Pop Culture, in Seattle, which was vilified last summer after someone noticed a placard there that read kurt cobain un–alived himself at 27. “Un-alived” is a zoomer euphemism designed to evade social-media censors, who prohibit talk of suicide. Its use regarding Cobain upset some Gen X crisis-counselor types who felt that it trivialized the act of taking one’s own life (and Nirvana). But I prefer “un-alived” to “suicided.” It’s so unromantic that it might actually stop people from killing themselves. In this way it feels millennial.