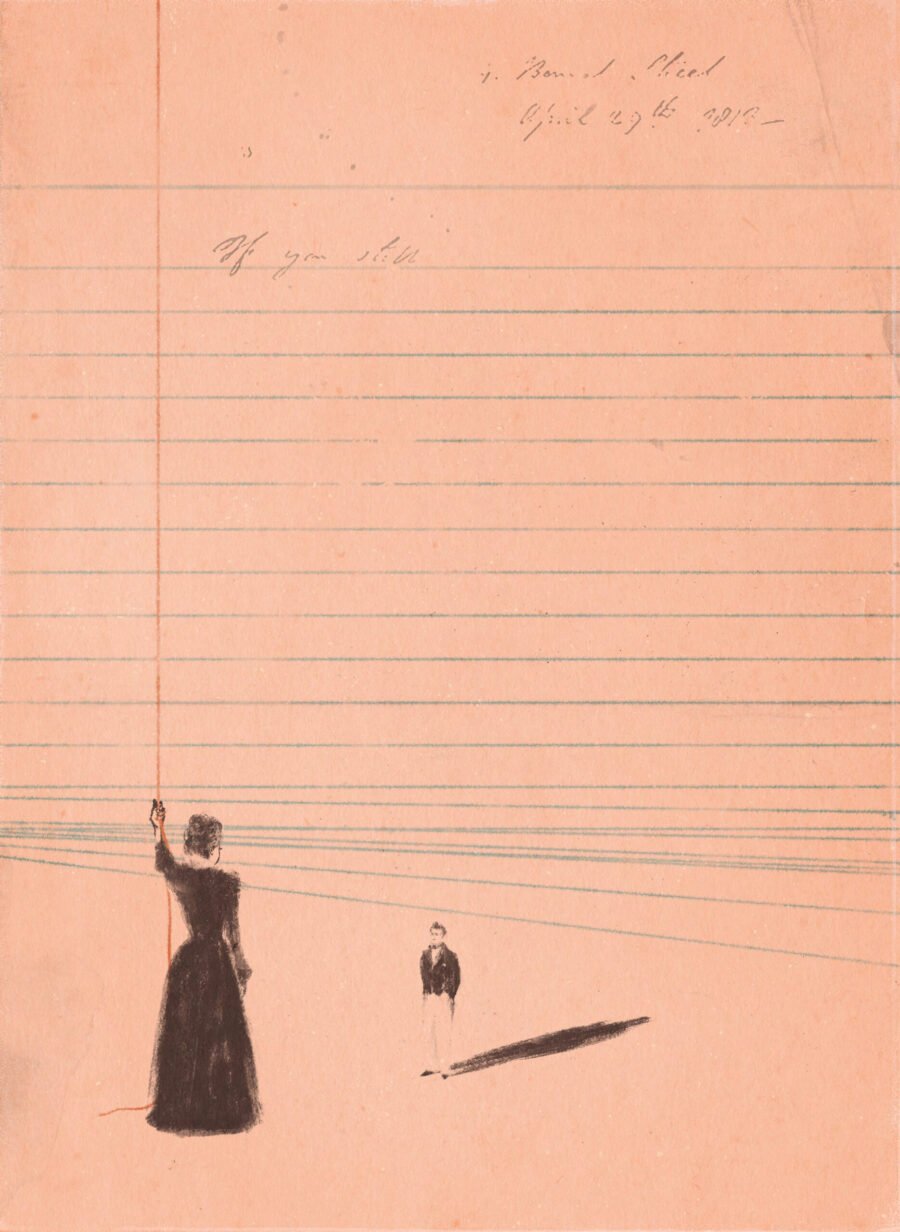

Illustrations by Patrik Svensson. Source image: A letter from Lord Byron to Lady Caroline Lamb, April 29, 1813. Courtesy the National Library of Scotland

Who can deny that the letter—pen, paper, envelope, stamp—is dead, incontrovertibly, relentlessly, unforgivably, unmistakably dead? Dead as a doornail. Dead as the dodo. Dead as the hundreds of generations who had no other way to convey ideas and emotions over distances of land and longing. The fountain pen, like the ink bottle it drank from, is now equivalent to an heirloom or an art object. The typewriter is as extinct as longhand. In the absence of the old-fashioned letter, speech is abbreviated, time itself is truncated, manners altered once and for all. Dear Mr. Smith is reduced to a speedy Hi. Can romance survive texting?

the letter as play

On March 9, 1812, Lady Caroline Lamb, a novelist, wrote a fan letter to George Gordon, Lord Byron, the poet who after publishing Childe Harold “awoke one morning to find myself famous.” This flamboyant proclamation is itself a reason for his fame. Lady Caroline’s far more limited renown rests less in her authorship than in her capturing Byron first as lover and then in a single phrase: “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” She penned him scores of heated letters; he replied with scores hotter yet. And when the furies of his love cooled, she went on pursuing him, and the words meant for him came back to define her own undiminished ardor.

There was a time when I ran after Lady Caroline as indefatigably as she ran after Byron. In a long-ago essay called “Lovesickness,” I stalked her, I mimicked her footsteps, I became her ventriloquist, even as she carried on with a rash of (so I wrote) spats and subterfuges and secret letters delivered to her lover by a page, who turned out to be Lady Caroline in disguise. For Byron she became a “little volcano,” a pest, an affliction, a plague, a fiend. She was a creature of ruse and caprice and jealousy; she would not let him go, she badgered him, she burned him in effigy, she stabbed herself. And she wrote him letters.

Why did I do it—why emulate her prickly quest, why invoke her reckless ghost? It was because of the letters. Letters, fragile shafts of paper and ink, can have the operatic force of stirring things up, making mischief, leaking lava, compelling notice, all while hiding under an imposture. The writer of letters, these silent arias, can be present though simultaneously fully absent. Letters! Exhilarating, teasing . . . and also innocent? I knew my prey; my prey was innocent. He was certainly not a lover. I had never so much as spoken a single syllable to him. But I knew his name and his fame.

His name was itself a marvel and an enigma: Sidney Morgenbesser. Better morning? Was this a regret over a lamentable yesterday, or a happy promise for tomorrow, or somehow both at once? And Sidney: Sir Philip Sidney, the sixteenth-century poet in his starched white ruff, cupbearer to the queen; or else Sidney Lanier, an American poet of the nineteenth-century South. However allusive these names might be to Elizabethan love sonnets or the Confederate landscape, Sidney Morgenbesser was nevertheless distinctly New York: an illustrious young professor of philosophy, celebrated for his lightning wit. His reputation was dauntingly fierce (or so I wrote):

He was an original. His supernal Mind crackled around him like an electric current, or like a charged whip fending off mortals less dazzlingly endowed. I had been maddened by a hero of imagination, a powerful sprite who could unravel the skeins of logic that braid human cognition. And so, magnetized and wanting to mystify, I put on a disguise and began my chase: I wrote letters. They were love letters; they were letters of enthrallment, of lovesickness. I addressed them to the philosopher’s university and signed them all, in passionately counterfeit handwriting, “Lady Caroline Lamb.”

I no longer remember how many letters (or how few) there were. To ensure anonymity, they were mailed directly from a central Manhattan post office, so as to evade more localized detection. It was an escapade and a frolic and a deceit and an act of pure play, conceived both in belief and unbelief, in declaration and concealment, in fulfillment and fear of exposure, in flagrancy and chagrin, in coveting and cravenness, in enchantment and dread. I hankered to live, above all, in a momentary maze of make-believe. My hope was to remain masked, but also to be found out. And ultimately I was found out, though I never learned how. Morgenbesser’s response? I heard that he laughed.

the letter as plot

Letters, in our common understanding, are not meant to be fiction, or jokes, or games, or tricks. They are not meant to compete with storytelling, and if they do, if they are dragooned into real life, they become conflated with conspiracy. Yet without letters, what would become of the crux of so many novels and plays? Of literature itself? Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein sets out with a series of letters; more letters fever it forward. Had Mr. Darcy not hand-delivered his letter to Elizabeth Bennet, she—who could brook neither fools nor snobs—might have lived unwed. If Romeo had read Friar Laurence’s letter, he and Juliet would have averted their misconstrued deaths. Acclaimed eighteenth-century epistolary novels—Pamela, Fanny Hill, Clarissa—could not have come into being, at least not in their chosen form; nor could Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, or Bellow’s Herzog. If not for a letter to his aunt, Marlow, the protagonist of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, would have been obliged to discover another contrivance to introduce his journey up the Congo. And what of the mute and final revelation of Melville’s Bartleby: his origin in the Dead Letter Office?

the letter as confession

The eminent midcentury cultural essayist Lionel Trilling—he resisted the phrase “literary critic,” by which he was always defined—is, as an influence, now in startling eclipse. Yet he remains painfully on the scene as a template for radical disappointment, for grievance against the self, for the failure of success. An abundant selection of Trilling’s letters attests to these ruminations, as well as the journals and an abandoned attempt at another novel. It is here, in this hoped-for renewal of storytelling, that a character proclaims “novel or nothing”—a cry that became an underlying regret for Trilling himself, and a theme he never betrayed by contradiction or inconsistency. He spoke of it in a public talk, he spoke of it in letters, he spoke of it in his journal.

In a lecture subdued by melancholia, he admitted:

I am always surprised when I hear myself referred to as a critic. . . . If I ask myself why this is so, the answer would seem to be that in some sense I did not ever undertake to be a critic. . . . The plan that did please my thought was certainly literary, but what it envisaged was the career of a novelist. To this intention, criticism, when eventually I began to practice it, was always secondary, an afterthought: in short, not a vocation but an avocation.

And in a perfervid entry in his journal, where “writer” can only mean novelist, he cuttingly dismisses a lifetime of probing expository prose as emasculating:

My being a professor and a much respected and even admired one is a great hoax. Suppose I were to believe that one could be a professor and a man! and a writer!

But it is in the intimacy of a letter, dated 1948, to John Crowe Ransom, poet and editor of The Kenyon Review, that he most poignantly confesses his regret:

At the present moment I find myself in an odd state of mind. . . . I find it hard to explain except as an impatience with myself in the role of critic which often presents itself as an impatience with literature itself. . . . But of course it isn’t that I don’t like literature, it’s that I don’t like my relation to literature. I don’t, I think, like myself in the critical and pedagogic role. . . . Whenever I feel my impatience I become frightened that I am regressing to some sort of terrible philistinism, and yet my bones keep crying out for something else that I am getting or giving. . . . Perhaps what I am saying is that my unconscious is requiring me to get back to fiction. My novel was, for me, only a very, very moderate success and yet it gives me the only satisfaction I can get out [of] years of writing.

The work that so buoyed him, The Middle of the Journey, had been published only the year before, and one review—by Robert Warshow, a writer he knew and trusted—left him discontented, and worse: angry and offended. Elsewhere, letter after letter is given over to defending the novel, often in minute analysis. At one moment, half in self-mockery, he taunts the naysayers: “These intellectual critics,” he sniffs, and soon after thinks ahead to “the new job,” the second novel that was destined to be smothered by ennui, which “will have greater simplicity, more time and space, more varieties of texture.” The old job, in such comments, is made to serve as a promissory note. And if there is an unwitting irony in these self-searing confessional letters, it is that—together with their wistfulness, their hurt, and their tender hope—they carry the tone, and the gravity, of the intellectual critic he had never wished to become.

the letter as motherhood

The strangest private love letters ever written from a mother to a daughter are also the liveliest, the wittiest, the most enchanting, the most observant, the most impassioned, the most inimitable, and were first circulated to be read aloud in the seventeenth-century court of Louis XIV, the Sun King. In another era, in a different society, the writer, Madame de Sévigné, might have been a novelist or an essayist, so attentive was she to mores and hairdos and human nature, illness and fashion and politics, gossip and feasting and folly—but it was her daughter, Françoise-Marguerite, to whom her most confidential emotions were nakedly addressed.

The letters have entered the mainstream of literature through a not-uncommon channel: family members separated by distance in an age when communication was limited to the earliest initiations of imperial postal delivery. Madame de Sévigné’s philandering husband was killed in a duel, leaving her widowed in Paris, the mother of a daughter and a son. When the daughter married the Comte de Grignan and moved to Provence, their correspondence began. Few of Françoise-Marguerite’s contributions survive, but Madame de Sévigné’s are with us in all their hundreds. They amaze, they delight, they entertain, they enlighten, and in their amorous oddity—verging on the erotic? the mystical? the Freudian?—they sometimes disconcert.

I received your letters, my bonne . . . I dissolve in tears when I read them. I feel as if my heart would break in two. . . . You love me, my dear child, and you tell me so in such a way that I cannot bear it without weeping copiously. . . . So, you enjoy thinking about me, talking about me, but you would rather write how you feel about me than to tell me so, face-to-face. However it is made known to me, it is received with a tenderness and a sensibility that is incomprehensible to anyone who is not capable of loving as I do. You arouse in me an unsurpassable tenderness; I think constantly of you. It is what the devout call “habitual thought”—the way one should think of God.

The aloof object of these praises was embarrassed by them, especially when they were displayed before an audience, causing the mother to beg the daughter “to trust me, and not to fear the exorbitancy of my love. . . . I implore you to make allowances for these failings of mine, for the sake of the sentiments which give rise to them.”

But the flood of sentiments overran the restraints:

I am so absolutely, so totally yours that it is impossible to add so much as an iota more. I would ask to kiss your pretty cheeks and to embrace you tenderly, but that would start me crying again.

Finally your letter comes, and here I am, all alone in my room, writing to you in reply, as I do with the greatest pleasure in the world. There is no greater delight in my life, and I live for the mail days when I write to you.

My God, how eagerly I await your letters! It is almost an hour since I received one!

Oh, my darling, how I wish I could see you, if only for a moment, to hear your voice, to embrace you, just see you pass by, if nothing more! . . . This separation racks my heart and soul—I feel it as if it were a physical pain.

No matter where I turn, where I look, I search in vain: that dear child whom I love with such a passion is two hundred leagues away from me. I no longer have her. At which thought I weep uncontrollably.

It is a love almost indistinguishable from elegy, from mourning the dead (at a time when the living young countess was pregnant six times in six years). Yet how is it possible not to succumb to the notion of lovesickness in the usual sense? And what might we think if a father spoke to a daughter in this voice? Even allowing for the difference in the speech and manners of the seventeenth and the twenty-first centuries, and for the chasm that lies between the language of the French nobility and the lingo on the New York subway, Madame de Sévigné does sound . . . odd. Or is it that we who have been too long steeped in Viennese Sacher torte cannot simply accept a mother’s outrageously flaunted adoration of a daughter for what it is, and nothing other?

the letter as loss

Letters are engines of connection, like a grandparent’s memory of a time beyond the newest generation’s reach; but they can also be portents of brutally broken bridges. My grandmother once told me (was it only once?), “I have two sisters, Galya and Feygetel, and Feygetel is my favorite.” These names come to me now as a kind of distant music. The sisters were left behind in 1906 in Hlusk, a small town in tsarist Belorussia—but Feygetel’s letters, in a Yiddish cursive too fluent and rapid for my insufficient literacy to decipher, were preserved (or shut up) for years in an old-fashioned suitcase on a half-forgotten shelf. My mother—who had arrived in New York as a nine-year-old immigrant child schooled in Yiddish and Russian—undertook to read them to me one afternoon in my teens; and it was then that I was captivated by the voice of my great-aunt: a shtetl Jane Austen! I was already familiar with reminiscences of Hlusk, the wooden sidewalks, the fear of the peasants’ dogs, the dread of Easter rioting, the numerus clausus deprivations, all the reasons for the journey in steerage to President Theodore Roosevelt’s America. But here, in Feygetel’s telling, was something else—laughter, wit, character, the unexpected corners and crannies of daily life, stories and stories! The intoxicating mind of my grandmother’s teasing, charming, satiric favorite sister.

The letters come to an end in 1938. Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial archive in Jerusalem, lists Feygetel’s fate:

First Name: Figetel [sic]

Last Name: Ozik [sic]

Gender: Female

Age: 46

Place of Birth: Glusk, Polesye, Belorussia, USSR

Father’s First Name: Yehuda

Mother’s First Name: Shoshana

Permanent Place of Residence: Glusk

Place During the War: Ghetto

Place of Death: Glusk

Date of Death: 1941

Cause of Death: Shot

Status According to Source: Murdered

Germany had by then invaded the Soviet Union, and Hlusk (“Glusk” as it appears on the map) in 1941 had been reduced to a starved and anguished prison awaiting destruction. The Jews of Hlusk were all marched out, lined up, and executed by the Einsatzgruppen, the volunteer local paramilitia uniformed and armed by the Germans. The vast majority of the Jews of Belorussia (close to one million) were either shot or herded into trucks to be gassed. Feygetel, voiceless, is less than a footnote: a grim item in a mournful inventory. Her effervescent letters, still in their suitcase and nowadays unread, remain perplexedly mute.

the letter as moral credo

Charles Eliot Norton, a Boston Brahmin and all-round savant residing in London, translator of Dante, professor of art history at Harvard, and in all other ways the sum of advanced Western civilization as defined by the Victorian elite, wrote to an American friend in 1869:

She is not received in general society, and the women who visit her are either so émancipée as not to mind what the world says about them, or have no social position to maintain. . . . No one whom I have heard speak, speaks in other than terms of respect of Mrs. Lewes, but the common feeling is that it will not do for society to condone so flagrant a breach as hers of a convention and a sentiment (to use no stronger terms) on which morality greatly relies for support. I suspect society is right in this.

Yet only a few days before, he and Mrs. Norton had themselves gone to call on Mrs. Lewes, who on Sunday afternoons kept open house for selected visitors. The breach she was guilty of? She had declared herself the wife of George Henry Lewes, a writer on philosophy, history, science, and literature—and a married man barred by law from divorce. Henry James, who at twenty-six was among those privileged to approach Mrs. Lewes, described her in a letter to his father:

To begin with she is magnificently ugly—deliciously hideous. She has a low forehead, a dull grey eye, a vast pendulous nose, a huge mouth, full of uneven teeth & a chin & jawbone. . . . Now in this vast ugliness resides a powerful beauty. . . . Yes, behold me literally in love with this great horse-faced bluestocking . . . an admirable physiognomy—a delightful expression, a voice soft and rich as that of a counseling angel—a mingled sagacity & sweetness—a broad hint of a great underlying world of reserve, knowledge, pride and power.

The rapture goes on and on, in phrase after embellished phrase. In all this there lurks a peculiar and very public irony: behold me literally in love in contradiction of I suspect society is right. George Eliot, the sibyl of Sunday receptions, was at the same time both a paragon of earnest sensibility and a social pariah. Her oceanic letters are nevertheless incarnations, or call them manifestos, of propriety and honor, exquisitely attentive, unfailingly sympathetic, attuned to the individuated integrity of each correspondent. The contemporary ear, habituated to distrust of sincerity, will await the cynical or dismissive note in vain; but when opposition is there to be countered, she will cleanly cut it away.

History, as it happens, brings us a remarkable confluence: an exchange of letters between the two nineteenth-century literary luminaries whose influential writing contributed to two separate upheavals of human understanding: the resuscitation of Jewish sovereignty and the abolition of chattel slavery. George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda (1876) preceded Theodor Herzl’s The Jewish State (1896) by twenty years, and promulgated the same aspiring principles. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) prepared the emotional ground for Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation (1863). What the two novelists had in common was indefatigable toil toward the highest good for the most demeaned and defenseless of peoples. Subjects that preoccupy them personally, though, are religion in one instance and, in another, Charlotte Brontë, nearly a quarter of a century dead, with whom Stowe claims to have communicated in a séance. George Eliot demurs:

Your experience with the planchette is amazing, but . . . is to me (whether rightly or not) so enormously improbable, that I could only accept it if every condition were laid bare, and every other explanation demonstrated to be impossible. . . . I must frankly confess that I have but a feeble interest in these doings. . . . At present it seems to me that to rest any fundamental part of religion on such a basis is a melancholy misguidance of men’s minds from the true sources of high and pure emotion.

And again: “As healthy, sane human beings we must love and hate—love what is good for mankind, and hate what is evil for mankind.” But as her novels reveal, straightforward rationalist Victorian rectitude of this kind covers over an underworld of shame and indignity, where ignorance, deceit, envy, avarice, foolishness, failure, and spite live on; where the child Dickens is maltreated, where Oscar Wilde suffers, where Mrs. Lewes herself endures shunning, all in the name of the high-minded teacherly credo that her letters proclaim.

the letter as advice column

The modern advice column began in the “women’s pages” of early-twentieth-century American newspapers. These were responses to bona fide letters on subjects as personal as any appeal to a trusted confidante, or even more so. A pioneer of this public exposure of private distress was Beatrice Fairfax, the pseudonym of Marie Manning, a novelist, journalist, and suffragist. The letter writer in such exchanges was identified only by first name, while her respondent was entirely fictitious: there was no sagacious motherly Beatrice Fairfax, both sympathetic and astringent, to relieve every conscience and unriddle every heart’s dilemma. Except for the price of a postage stamp (two cents in 1898, when the column was initiated), the consultation was free, and carried the solid reliability of earnest truth-telling:

I came from Ireland six months ago. A young man whom I have known since I was a little girl asked me to promise to marry him. . . . It was breaking my heart to come away, and I loved him dearly when he asked me. So I said yes. He is to come over as soon as he gets enough money. When I reached this country I met another young man. . . . I see him often, and I think I have fallen in love with him. It will kill my friend in Ireland if I am not true to him, and it will kill me if I have to be.

My Dear Nora: I am glad that you are, although apparently fickle, at least conscientious enough to be troubled by your fickleness. That is a sign that your heart is pretty nearly in the right place. . . . Don’t try to decide anything now. Don’t see the new young man much. . . . Remember that as an honest girl, you cannot encourage him while you are pledged to another.

And wait. Grow accustomed to your new surroundings and your new life. Then act as your heart directs. And be sure of this, Nora dear. It will not kill the young man if you should fail him. Death is not so easily accomplished.

At the same time, in New York, other immigrants found similar difficulties, but also problems peculiar to their origins. Abraham Cahan, the novelist befriended by William Dean Howells and the author of The Rise of David Levinsky, was also a founder and editor of the Forverts (the Forward), a Yiddish newspaper designed, in part, to ease Jewish newcomers into the ways of the goldene medina—the sanctuary and opportunities of America, the Golden Land. Though the Forverts ran essays and fiction by literary luminaries, among them Isaac Bashevis Singer, its most popular feature was its down-to-earth advice column, A Bintel Brief (“A Bundle of Letters”), inaugurated in 1906. Poverty, anxiety, desperation, and aspiration were typical subjects. And sometimes A Bundle of Letters could serve as the petitioner’s conscience:

Eight months ago I brought my beloved from Russia to America. We had been in love for seven years and were married shortly after her arrival. We were very happy together until my wife became ill. . . . You can hardly imagine our bitter lot. I had to work in the shop and my sick wife lay alone at home. Once when I opened the door at dinnertime. . . . I saw she was out of her head with a fever. . . . I was supposed to run back to the shop because the last whistle was about to blow, but I couldn’t leave. I knew that my boss would fire me. . . . There wouldn’t be a penny in the house. . . . I jumped up and began to run around the room in despair. I leaped to the gas jet, opened the valve, and then lay down in the bed next to my wife and embraced her. In a few minutes I was nearer death than she. Suddenly she cried out, “Water, water!” With my last ounce of strength I dragged myself from the bed and closed the gas jet. . . . After fourteen days she got well. Now I am happy that we are alive, but I keep thinking of what almost happened to us. Until now, I never told anyone about it. I have no secrets from my wife, and I want to know, shall I tell her all, or not mention it.

This cri de coeur does not tell all. Without a penny in the house, what could be the outcome of so much anguish? Did the writer lose his job? The editor’s reply was succinct:

This sad letter about the life of a worker is more powerful than any protest against the inequality between rich and poor. The advice to the writer is that he should not tell his wife that he almost ended both their lives. This secret may be withheld since it is clear he keeps it out of love.

The tone of both the entreaty and the answer in these early letters suggests that serious authority is invested in the columnist, and that the trouble, once expressed, will soon be satisfactorily dispatched. It was in this same era that another source of elemental trust arose: “the talking cure.” But psychoanalysis was, and remains, costly and often unlimited. A patient may go for years without resolution. Was the newspaper advice column at its most solemn, appealed to by the poor and the time-harried, a speedier, more efficient writing cure? (One may ask this solemnly, or not.)

Beatrice Fairfax and A Bintel Brief (renewed at the online English-language Forward) have since had their latter-day successors, most notably the twin sisters Esther Pauline Friedman Lederer and Pauline Esther Friedman Phillips, known respectively as Ann Landers and Abigail Van Buren (“Dear Abby”). They too have succumbed to the tides of time, while the digital universe accommodates new figures of salvation in countless venues. And it may be here—in the most up-to-date advice columns—that the impersonally public personal letter is . . . well, not quite alive in the sense of an enduring private relationship, but at least partly undead.

the letter as greeting card

The most insidious betrayer of letter writing comes subtly, prettily, artfully, as an impostor pretending to be the letter’s harmless twin: it comes in the mail as a look-alike, with handwritten signature, postage, envelope personally addressed. And everything that the unforgotten letter did best, the greeting card excels at. It is a model of decorum and proportion when suitable. It can be antic and witty, off-color enough for an innocent good laugh, tenderly sympathetic, touchingly romantic, decorative and painterly, exuberant or grave. It knows how to choose the apt phrase for every conceivable circumstance of human life, from first day of school to funeral. It ameliorates hurt, heals past offense, and exorcises loneliness. It is, always and always, Thinking of You. Whether inexpensive or costly, it is reliably time-saving, and relieves the sender of hard-won mulling over the right word. It is as ingenious as ventriloquism, made possible by some humble hireling rhymester drudging away at a keyboard in a faraway office.

But what the greeting card cannot do is what the letter never failed to deliver: the news. News of births, of deaths, of jobs, moves from one neighborhood to another, or from city to city; news of reactions to the news, local, presidential, international; news of rumors and scandals, news of movies seen, books read, meals cooked, restaurants visited; news of trips to the dentist, the zoo, the beach, the aquarium, the planetarium, the art museum, the circus; news of the knees, the stomach, the heart, the lungs.

And when the ready-made card—that handy surrogate for intimacy—left behind its old character to take on twenty-first-century messaging, what marvels of digital animation irrupted, comical beasts leaping and flying, suns rising, candles glimmering, buds blooming, melodies swarming! So much motion and dazzle, while the more indolent paper card rests on the mantel for a season, or is put away, together with photos of unidentifiable persons, to be disposed of as meaningless one or two generations later. Is it conceivable that the venerable greeting card too must come to rest in the museum of the obsolete?

the letter as history

But if even the greeting card is transformed into yet another digital feat—losing its façade as a pretend letter—a new question arises: In the absence of private exchanges, what will happen to history? How will biography fare? What of the unwritten letters of persuasion that will have left no trace, letters of importuning gone unrecorded, letters of reprimand that never materialized: Letters that contain the might-have-been?

Had Henry VIII’s wooing letter to Anne Boleyn, with its intimations of mutual “specialities” yielding comfort to both, not won her, would she have kept her head?

As touching our other affairs, I assure you there can be no more done, nor more diligence used, nor all manner of dangers better both foreseen and provided for, so that I trust it shall be hereafter to both our comfort, the specialities whereof were both too long to be written, and hardly by messenger to be declared. Written with the hand of him which I would were yours.

Might Princess Catherine of Aragon—who preceded Anne Boleyn as the wife of Henry VIII, a marriage that was annulled—have forestalled the Reformation if only she had dealt with Anne as Katherine Mansfield in 1921 did with Princess Elizabeth Bibesco of Romania?

I am afraid you must stop writing these little love letters to my husband while he and I live together. It is one of the things which is not done in our world. You are very young. Won’t you ask your husband to explain to you the impossibility of such a situation. Please do not make me write to you again. I do not like scolding people and I simply hate having to teach them manners.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill, luckily, did not heed the advice of Eliot Crawshay-Williams, his private secretary, who in 1940, after the fall of France, wrote that Britain with regard to Nazi Germany ought to implement its “nuisance value while we have one to get the best peace terms possible. Otherwise, after losing many lives and much money, we shall merely find ourselves in the position of France—or worse.” To which Churchill replied with a scalding: “I am ashamed of you for writing such a letter. I return it to you—to burn and forget.” (It was sold at auction seventy years later.)

Once in a span of centuries comes a Galileo moment, when an unsuspected insight into the workings of nature alters human understanding and civilization itself, but is resisted as contra divine revelation. Gauzily elusive legend, not the written evidence of history, tells us of Galileo’s whispered defiance of the Inquisition: Eppur si muove! Yet it is in an actual letter, as alive now as it was at the instant of the scratch of his pen, that Charles Darwin was led to defend the radical disclosure of his theory of evolution from the charge of atheism. In May 1860, the year after the publication of On the Origin of Species, he writes to Asa Gray, the eminent botanist:

I had no intention to write atheistically. But I own that I cannot see . . . evidence of design and beneficence on all sides of us. There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidae with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice. . . . I am inclined to look at everything as resulting from designed laws, with the details, whether good or bad, left to the working out of what we may call chance. . . . I feel most deeply that the whole subject is too profound for the human intellect. A dog might as well speculate on the mind of Newton.

In its time and place, never was a letter more daring—or more diffident. That it exists at all is a wonder of good fortune: to witness firsthand the awe and dread one of the greatest empirical innovators undergoes in contemplation of his own conviction.

the letter as exhibit

Letters set down by immortals—the writers acclaimed as such by posterity—can be found under glass in temperature-controlled rooms in honored institutions. How distant they are then from the hour of their birth and the living hands of their recipients! Under display they endure a metamorphosis that challenges philosophic clarity: How is it that the very thing that was performed in the light of the everyday is now construed as an inviolable prize, protected, guarded, often by uniformed men with guns?

It is as if meaningfulness itself becomes unstable—kin to Alice after she nibbles the mushroom, or Einstein after he topples Newton, or Darwin after he undoes biological immutability. A letter preserved in a vitrine takes on a certain sacral aura—not unlike a saint’s finger bone revered as a holy relic.

Though the museum is the most familiar such sanctum, there is another—transient, ephemeral, and far noisier: the auction house. While visitors to the Morgan Library’s current exhibit of a collection of Kafka’s letters, postcards, photographs and diaries may be mesmerized by pangs of pathos or enthrallment, they will be barred from taking any of these treasures home. The auction house, in contrast, promotes acquisition, and it was at Sotheby’s not long ago that one of Kafka’s last letters was sold, transfigured not only by time and fame, but by its very presence in a voracious commercial setting: itself a Kafkan scenario.

Addressed to Albert Ehrenstein, a poet and editor, it was sent from a sanitorium during Kafka’s treatment for tuberculosis:

I haven’t written anything for three years, what’s been published now are old things, not even something I’ve started. . . . When worries have penetrated to a certain level of existence, the writing and the complaining obviously stop. My resistance was not all that strong either.

These mundane lines of hopelessness, frequent also in Kafka’s journals, verge on the calamitous, and all the more so as illness overwhelms them. Here there is no artistry, no recognizable subversive Kafkan idiom. And yet: the dismal pressure of confinement, the speeding stream of longhand, the clear knowledge that this simple communication stands as the living strand of a brief and consequential span of a writer’s breath, inexorably seizes our gaze. In lieu of awe, pity: pity as a particle of the hallowed.

For a different species of exhibit, turn to Project Gutenberg, founded in 1971, a free online archive of more than seventy thousand e-books, where the ghosts of letters are kept safe in cyberspace, their words maintained not in paper and ink but all the same visibly, reverentially. The act of scrolling with a mouse in hand is no match for a stroll in museum halls, peering into case after case, but in the Gutenberg’s digital archive a dedicated sense of the consecrated nevertheless persists.

Thoreau, living at the time in Staten Island, writing to Emerson on June 8, 1843:

I have been to see Henry James, and like him very much. It was a great pleasure to meet him. It makes humanity seem more erect and respectable. I never was more kindly and faithfully catechized. It made me respect myself more to be thought worthy of such wise questions. He is a man, and takes his own way, or stands still in his own place. I know of no one so patient and determined to have the good of you. It is almost friendship, such plain and human dealing. I think that he will not write or speak inspiringly; but he is a refreshing, forward-looking and forward-moving man, and he has naturalized and humanized New York for me.

“I think that he will not write or speak inspiringly”? We may read this in surprise. But it was not the novelist whom Thoreau visited in 1843; it was Henry James Sr., the spiritually inclined father. The novelist himself was at the time asleep in his cradle, two months old.

Mark Twain to his brother Orion Clemens, August 11, 1872:

What I wish to put on record now is my new invention. . . . My idea is this: Make a scrap book with leaves veneered or coated with gum-stickum of some kind; wet the page with sponge, brush, rag, or tongue, and dab on your scraps like postage stamps. . . . The name of this thing is “Mark Twain’s Self-Pasting Scrap Book.”

T. S. Eliot to Emily Hale (a steady correspondent in a long-standing relationship that she mistakenly believed would culminate in marriage), April 12, 1932:

April is an unkind month, but perhaps May nowadays is still unkinder: I always find the first burst of spring, and the last glory of autumn, the two moments most troubling to my equilibrium and the most reviving of memories one must subdue. . . . One cannot help coming to the surface at times with a realization of how intense life can be—or how it was—or how it might have been. . . . But I do always feel convinced that every moment matters, and that one is always following a curve either up or down . . . and that the goal is something which cannot be measured at all in terms of “happiness”—whatever “the peace that passeth understanding” is, it is nothing like “happiness,” which will fade into invisibility beside it, so that happiness or unhappiness does not matter.

In these letters, each a tongue and a temper directed explicitly to a single consciousness, Kafka shows himself to be Kafka, and no one else; Thoreau to be Thoreau, and no one else; Mark Twain to be Samuel Clemens, and no one else; and T. S. Eliot to be Prufrock and no one else. Which is by way of saying that letters are unduplicable fingerprints; and fingerprints may be, after all, what we mean when we speak of soul.

the letter as existential quarrel

Oand I met in graduate school in a department of English where the professors were called, in Oxonian style, Mister, and where the New Criticism was irreversible dogma. He was spectacled, of compact stature and formidable mien, and spoke with an unidentifiable accent that might, if you were tempted to think so, suggest a British facsimile. He was also ferociously, rabidly, intellectual, and kept the rest of us always in fear of being found out for what we really were: inferior, seriously uncultivated, dumb. At the time I never suspected that this was theater; but it was the theater of consummate self-belief.

Backstage, hidden from the proscenium, he was a Jewish refugee child who had fled with his family from an Antwerp occupied and terrorized by Nazi Germany, and had come into the haven of America at age twelve. French was his first and permanent language, and English became his second and equally permanent language. He is poet, parabolist, playwright, scholar, critic, philosopher (of a kind), and professor. His published work is gargantuan, effulgent, sizzling with wit and brio, wise in the way of Aesop and Puck, of Molière and Diderot. He is, besides, wounded, lonely, melancholic, skeptical, cynical, resentful; he feels cheated by life, by circumstance, by the elusive riddle of fame.

And since he and I are both well into longevity, our contentious decades-long friendship has imploded many times, once so combustibly that a breach (of my making) lasted several years. The cause? You might call it cultural, or political, or temperamental, or ancestral, or anything easily definable by explicit category; but what forced it is something more profoundly organic, instinctive, while at the same time atmospheric, ceremonial: it is everything implicit in the term Weltanschauung—embedded less in “worldview” than in fixation, or fanaticism, or madness. Its source is the idea of allegiance. O is not simply indifferent to or estranged from any allegiance; he repudiates it outright, as if born fully formed on Mount Olympus out of the head of Athena. His purist detachment is itself a version of fanaticism. He never speaks of mother, father, sister, personal history. He summers in Paris as if he possesses it by heritage. For himself, no other heritage closer to home can touch him: Molière and Diderot are enough, and if they seem a little displaced on American soil, so be it.

And so we clash, and clashed day before yesterday yet again. Our conflict is nowadays wholly epistolary. It is more than half a century since O and I last met in the flesh. On my part, I am indebted to, and grateful for, allegiance: to my mother and her life, my father and his life, my grandmother and her life, and to what I have learned from their histories; I am indebted to, and grateful for, libraries and literature and liberty and nationhood in its individuated expression. My allegiances own a habitation and a name. O, in contrast, floats free, believing himself unfettered, quick to mock and scorn; for him, any allegiance is primitive, tribal, unbecoming to that superior wraith he imagines himself to be—Universal Humankind. So preposterous is this position that one is disposed to ask: Where is the painting, where the symphony, the poetry, the astronomy, the healing discovery, the governmental insight, that the chimera of Universal Humankind has given to the world?

To O I wrote in a furious email:

What a pity that you are so bifurcated, or ought I to say so characterized by personality schism, or Jekyll-and-Hyde affliction! There is so much that is ingeniously enchanting, the matchless intellect, the genius expressed in many languages, that I must grieve for the mad fool who abides with all the imperial rest. It’s as if you are not merely threadbare but bare, a naked declaimer stripped of all history, of all knowledge, all memory, all intellectual capacity, all reverence for things humane, all simple morality, and more: the capacity to imagine what the moral life could be. History will not know you. You never were. You never will be.

O’s reply:

To my eyes and ears, you appear to be seriously demented. Demented, that is, in a single though large area of the mind, while perfectly rational and intelligent everywhere else. Like one deadly mushroom in a basketful of a variety of delicious ones. Demented people don’t know they have “lost it” (as one says). Fortunately, as far as I can tell, this condition of yours doesn’t affect your general dealings with the world. It is truly a one-spot wound of the mind.

To this he appended: “Probably the final words between us.” They were not; there followed another round or two (I accused him of pilfering for his own copycat use my charge of selective dementia), and my own final words: “I once vowed I’d never be responsible for another breach, so if yours are ‘the final words,’ it is your doing, not mine.”

And then came O’s final (so far) words, in red letters: “No no! I’m staying.”

And so, after all, am I.