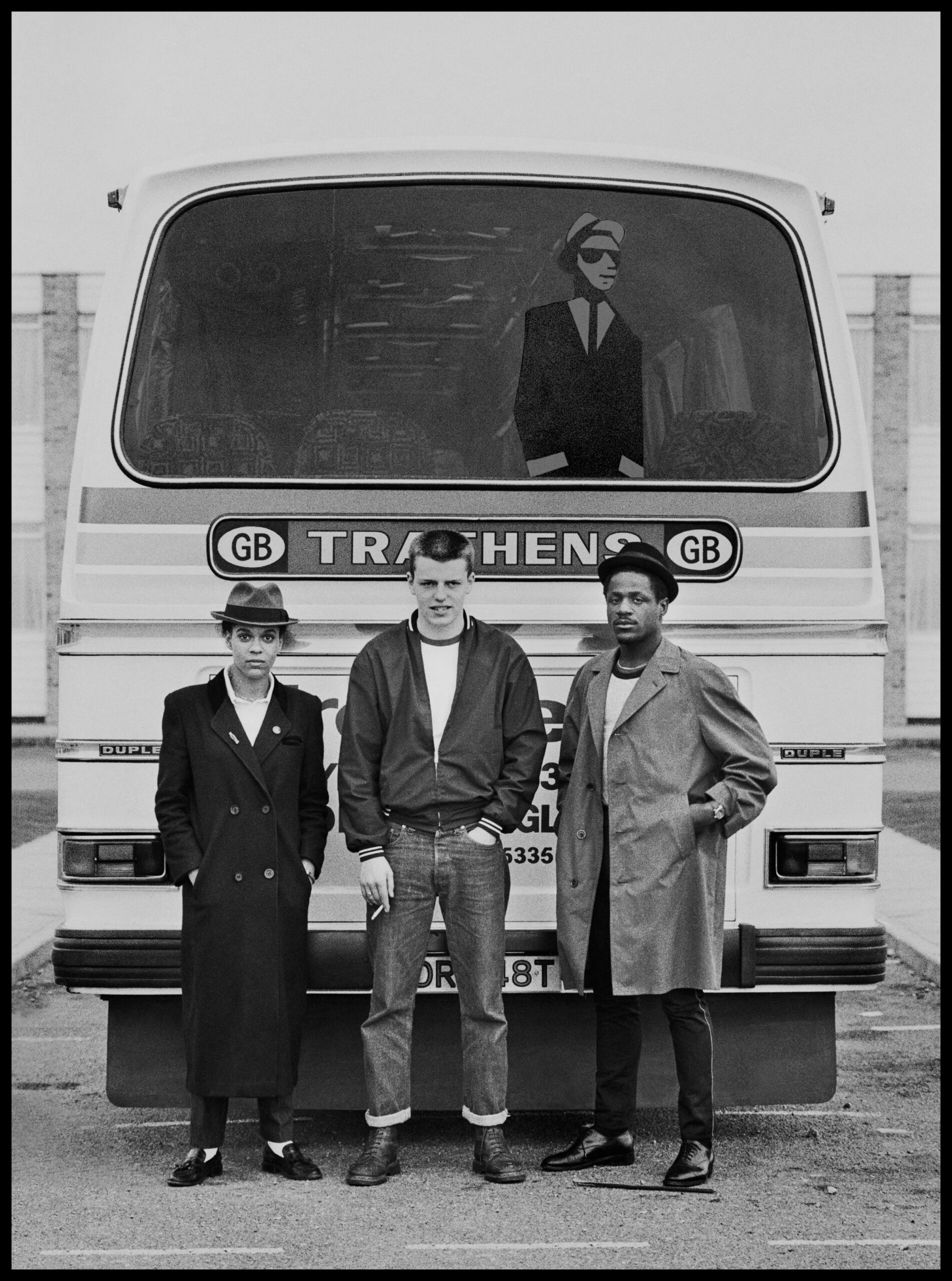

The Specials © Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Discussed in this essay:

Too Much Too Young, the 2 Tone Records Story: Rude Boys, Racism, and the Soundtrack of a Generation, by Daniel Rachel. Akashic Books. 480 pages. $32.95.

When I was asked recently what gigs I’d most want to see if I could travel back in time, a few obvious answers leaped to mind: Charlie Parker, the Velvet Underground, Dylan and the Band c. 1965–66. Truly, what I’d most like to do is revisit certain nights in the late Seventies in a less altered state than I was in at the time: the Fall, Joy Division, Pere Ubu, Wire. Also on that list: one night in the spring of 1979, when, down in the basement of the Hope and Anchor, a raucous crowd witnessed an early London performance by the Specials.

To say it was packed doesn’t do it justice. It had its own weather system: clouds of body heat, beer fumes, a fug of cigarette smoke curled around a passel of porkpie hats. A carnival squeezed into a cupboard. And this one abiding mystery of nightlife physics: How do people dance in such situations, let alone make the piston-elbowed, knees-up motion eternally associated with ska?

There were members of various London bands in that sauna of a room, keen to check out the buzz around these Midlands interlopers. An unruly bunch, on first acquaintance—two of them black, five white, and all distinctly un-posey. Was this serious competition, or a passing fad? What no one—not even the Specials themselves—could have foreseen was how big they would become, and how soon. Not just big within this or that underground scene, but tabloid big, television big, young-kids-dressing-like-you big. In the early Eighties, bands like the Human League and Culture Club also attained such world-seducing status, but they were explicitly pop and always had their mascaraed eyes on the prize. The Specials were something you couldn’t plot on a graph; their revved-up combo of punk rock and Jamaican ska planted a seed that wrought unlikely blooms.

Only a few months after the North London show I saw, the record label Chrysalis signed up the Specials; their leader, Jerry Dammers, insisted the band retain its own independent imprint, 2 Tone. Other ska-adjacent U.K. bands—Madness, the Beat, the Selecter—made a beeline for 2 Tone, and the reverberations would eventually encircle the globe. Ska as rendered by the 2 Tone crew was a protest-any-hegemony template that took root in the most improbable places: Orange County, California; the Basque country of Spain; Russia; China; Venezuela; Argentina. Read the comments on YouTube under the 2021 BBC documentary 2 Tone: The Sound of Coventry: the listeners who say they were blown away by them in their heyday, alongside newer converts who find them inspiring today, range from a “rude girl” from the Philippines to people in Boston, California, and Holland. Someone from Belfast remembers how, “at the height of the Troubles, the Specials meant so much to me”; a middle-aged Scot writes that the Specials “taught me as a 8 year old laddie in Edinburgh how damm [sic] stupid racism is.”

What was it about this intensely local phenomenon—straddling Jamaica and the Midlands—that allowed it to become a musical Esperanto? This is a ghost story of sorts, written in cycles and loops, loafers and suits, ornery protest and wired-to-the-skies dance weekends.

Daniel Rachel’s astute and thorough Too Much Too Young, the 2 Tone Records Story: Rude Boys, Racism, and the Soundtrack of a Generation opens on a calamitous night in 1940, when the West Midlands city of Coventry was smashed like a cabinet of delicate ornaments in a bombing raid by Hitler’s Luftwaffe. It was left a ghost town, like many such European conurbations. The wasteland would be cleared to make way for a new postwar dream of tower blocks and housing estates, as well as a striking new modernist cathedral designed by Basil Spence, built adjacent to the ruins of the original.

In the mid-twentieth century, Coventry, along with its close neighbor Birmingham, became the site of successive waves of immigration from the British Commonwealth, including the Caribbean. Starting in 1948, members of the so-called Windrush Generation, newly granted the right to live and work in the United Kingdom, took positions in car factories, public transportation, and the National Health Service; they also made necessary and long-lasting changes to British culture. In 1962, the same year the new St. Michael’s Cathedral was consecrated with Benjamin Britten’s specially commissioned War Requiem, Coventry was declared a twin city of Kingston, Jamaica, where ska was in its infancy.

The Coventry bombing raid is an apt place for Rachel’s story to begin—when people are crushed or stifled, they regroup and rebuild and reimagine—but there are so many other places you might pick as a starting point for this tale. The southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Fifties New Orleans. A British art school or two. Or: the New York World’s Fair of 1964, the “biggest global shop-window of the day,” where Jamaica presented a reggae fan’s dream lineup, including Jimmy Cliff, Prince Buster, and Millie Small (of “My Boy Lollipop” fame), all backed by Byron Lee and the Dragonaires. The program had been put together by Edward Seaga, then the country’s head of welfare and development, who would go on to become prime minister and stand onstage with Bob Marley.

Too Much Too Young doesn’t delve too deeply into the background of Jamaican ska, and for good reason—it would necessitate a whole other history. An excellent primer is Lloyd Bradley’s Bass Culture: When Reggae Was King, from 2000, which details the origins of ska in the sound-system culture of Jamaica. In their earliest manifestation, sound systems—portable units of speaker cabinets and turntables, helmed by charismatic DJs—played imported American R&B at bone-crunching volume at various outdoor events around Kingston. The popularity of a sound system depended on obtaining exclusive Stateside tracks, and perennial favorites included sides by Fats Domino, Professor Longhair, Jimmy Reed, and Bill “Mr. Honky Tonk” Doggett, as well as jazzers like Dizzy Gillespie and Earl Hines. When the finite supply of old R&B 45s was exhausted, the sound-system bosses started to produce crowd-pleasing sides of their own. A lot of the musicians roped in for this had attended the Alpha Boys’ School, a strict Catholic institution where prayer was taught with a side order of musical theory. One of its lucky alumni was the trombone player Rico Rodriguez. Born in Cuba in 1934, he played with the famous Skatalites and recorded with such sound-system luminaries as Prince Buster, Clement Dodd, and Duke Reid.

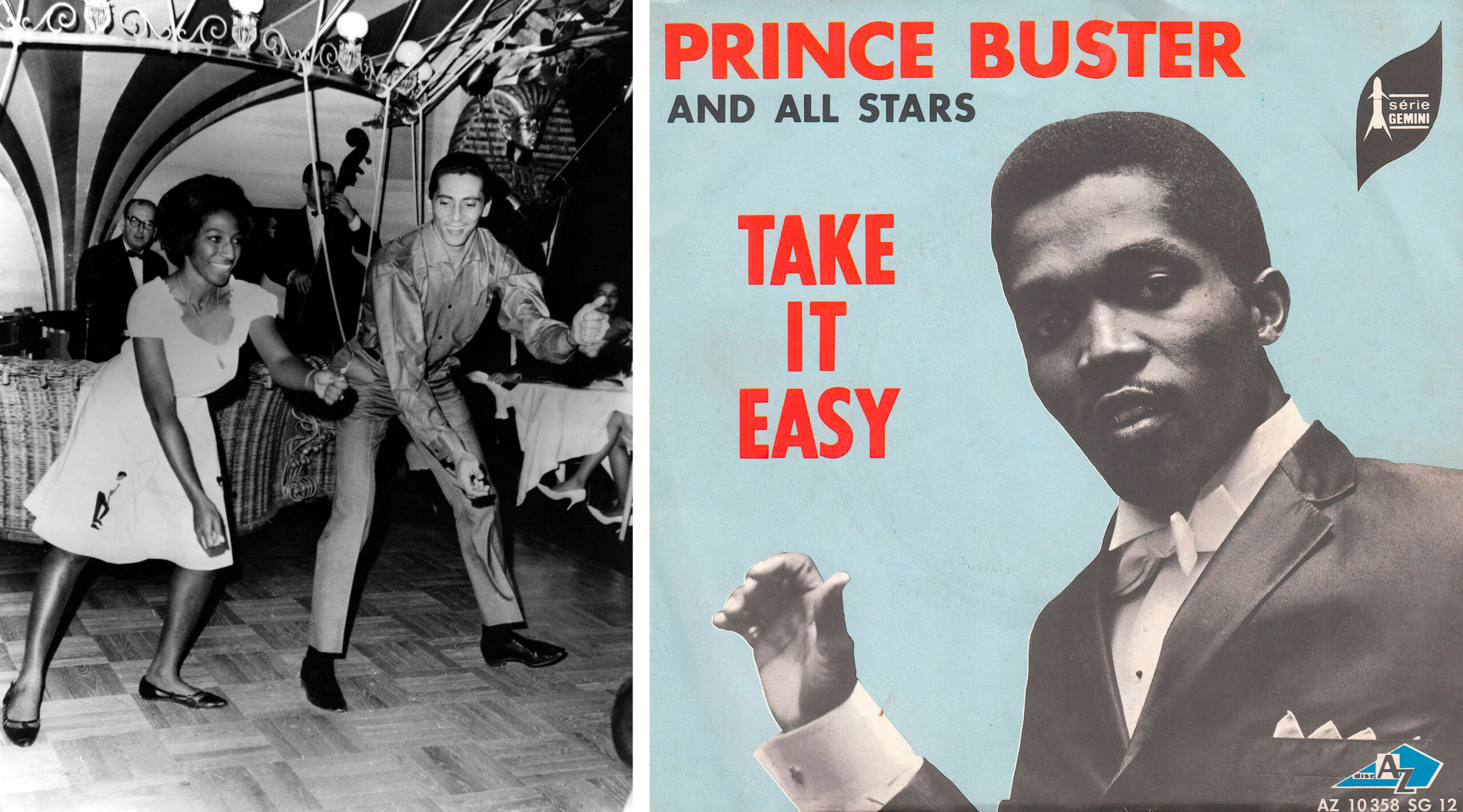

Many of these first-wave ska musicians considered jazz their real calling, and it’s easy to detect the ghost of big band’s thunder in ska’s own drum-and-horn-led sound; like beboppers, a lot of them dressed in exquisitely baggy suits and natty porkpie hats. When the Windrush Generation left Jamaica, this musical culture came with them to the United Kingdom. (In 1961, Rodriguez moved to England, where he worked on the production line at Ford’s Dagenham factory; he later added his distinctive sound to some of the Specials’ best-known songs. A number of excellent Afro-Caribbean jazz musicians had also made the journey over—Joe Harriott, Harold McNair, Harry Beckett—and revitalized British jazz in the process.) A small alternative economy sprang up around rent parties, record shops, and homemade sound systems. By 1963, ska was a going concern in England, and, in Lloyd Bradley’s words, had “moved up from the shebeens of Ladbroke Grove into London’s West End.” (There is a great black-and-white clip from 1964 of the oleaginous TV presenter Alan Whicker on the BBC’s Tonight: “Any moment now, there’s gonna be a fierce outbreak of ska!”) Following the Profumo affair in 1963—a scandal that involved the British secretary of state for war lying about his extramarital affair with a nineteen-year-old model named Christine Keeler, who might also have been sleeping with a Soviet spy—the Jamaican saxophonist Roland Alphonso cut a tune titled with Keeler’s name, and the sound-system duo King Edwards put out a track called “Russian Roulette.” You don’t really think of ska as the soundtrack to the Cold War, but these songs demonstrate how easily it could take on the camouflage of successive times and places.

Left: A Jamaican couple dancing at the Drake Hotel in New York City, 1964 © Smith Archive/ Alamy. Right: Cover art for a record by Prince Buster and the All Stars © Records/Alamy

For many Jamaican kids in the United Kingdom, ska was mum-and-dad music rather than some dizzying new outlaw sound, but those same parents associated its up-tempo swing with the Jamaican Independence Act of 1962. History in a horn arrangement! It begins as a shuffle but soon becomes an unstoppable march. What ska had imbibed from American jazz and R&B was a musical ESP about where to put the emphasis and where to leave some space. It called out for a new way of moving—picture someone strolling down a city street who suddenly breaks into an agitated, quasi-military trot. Reggae was a slow skank, feeling the earth between your toes; ska was Saturday-night show-out and exuberance—lean, jangled, calisthenic. Like they did with Northern soul and rockabilly, British youth took this elsewhere music and made it over according to their own exacting style diktats. Mods took up ska alongside their established playlist of imported soul and up-tempo jazz. At London clubs like the Flamingo and the Marquee, black mods began to pop up on this pale-peacock scene. Bradley:

Many social commentators of the day pointed out that the physical proximity of the indigenous working-class mods and newly arrived immigrants—on council housing estates and in the workplace—fostered such cultural alliances.

This mixing and mingling—personal, stylistic, musical—would set a template for many things to come in U.K. youth culture, from the Equals to the Specials to Massive Attack and beyond.

The Specials came from a many-limbed sprawl of different backgrounds, birth years, and temperaments. Both Neville Staple and Lynval Golding had immigrated with their families from Jamaica. Terry Hall grew up in Hillfields, on the edge of Coventry’s city center. Drummer John Bradbury came from a working-class Irish background and had had a musical apprenticeship playing in workingmen’s clubs. Bassist Horace Panter was from the genteel middle-class market town of Kettering. In 2 Tone: The Sound of Coventry, the likably over-the-top impresario Pete Waterman describes an early meeting with the band as resembling a cartoon, like some real-life version of Top Cat. The 2 Tone logo used on labels, sleeves, PR material, and posters was itself a cartoon: a cool-looking, mod-ish character dubbed Walt Jabsco, based on a photograph of the young Peter Tosh. Walt was the visual equivalent of a pop hook: clear, snappy, dispelling all portentousness.

It probably wouldn’t have happened exactly the way it did if Jeremy David Hounsell Dammers didn’t have the background he did. Dammers was born in 1955 in Tamil Nadu, where his father, Horace, served as a chaplain at a missionary school. The family moved back to the United Kingdom when Dammers was two years old and settled in Coventry when he was ten. Pa Dammers seems to have been one forward-looking cat. In 1972, he established the Life Style Movement, whose ethos was to “live simply, so that others could simply live.” The movement was founded on the understanding that resources are finite, and it attracted individuals who sympathized with the idea that “there is enough for everyone’s need, but not enough for anyone’s greed.” Already detectable here is the same mix of utopian politics and pragmatic can-do that would shape the emerging ethos of 2 Tone.

A photograph by Chalkie Davies of Pauline Black, Suggs, and Neville Staple with their tour bus at a stop in Brighton during a 2 Tone tour, 1979 © The artist

Dammers belonged to a generation that was pushed to pass the notorious eleven-plus exam and get into one of the United Kingdom’s supposedly superior grammar schools. He seems to have been one of those kids who was smart and resourceful but always itching to go against the grain. As Rachel tells it, he left school with one O level in art and took a foundation course at Nottingham. For an interview at an arts school in Leeds, he turned up without a portfolio, informing the admissions panel that he wanted to create a work of Pop Art that would be like a “modern version of the Who.” Such conceptual brio was not welcomed, and he accepted a place at his second choice, Lanchester Poly, in Coventry. There Dammers made a series of short films about boxing, the IRA, and one called Doing the Bump at Barbarella’s, which used, in Rachel’s words, a “ ‘funky reggae-ish’ instrumental soundtrack created by Jerry and a student from the year below.” The student in question, Horace Panter, would later play bass for the Specials; the music they worked up would eventually gel into a Specials track called “Nite Klub.”

Already obsessed with music—Prince Buster, the Small Faces, and the Who composed his basic mod curriculum—Dammers experienced an unlikely mid-Seventies epiphany in the eclectic pub rock of Graham Parker and the Rumour, a band that combined gritty R&B, Dylanesque finger-pointing, reggae, and country music. Dammers’s recollection of this time will strike a chord with many people who were there:

For me, reggae made punk gigs bearable. The lyrics may have been good, but the music was more or less unlistenable. To actually sit down and listen to a Sex Pistols LP . . . I mean, who’d do that? It gave me a headache. I wanted to create a more mixed atmosphere.

Reggae was both contemplative and irate, loved-up and aggrieved, an avowed roots music whose dizzying dub mixes seemed to suit the brutalist architecture of Seventies Britain. Reggae’s singers and players weren’t, for the most part, aloof superstars, but remained part of their communities, giving voice to local woes. They could also—after the manner of Dammers’s own father—combine utopian dreaming with hard-edged politics, as per Prince Jazzbo’s “Run capitalist / I and I want socialist!” or Tapper Zukie’s paean to the Russian-backed Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola.

Dammers’s eureka insight was to combine the urgent velocity of the Clash with the more layered elasticity of reggae, although the Specials were never just copycats. Bass, drums, and keyboards did emphasize the offbeat, but as the band’s lead guitarist, Roddy Byers, put it, there were also “disco basslines, heavy metal passages, rock riffs, and all sorts coming out over the ska.” This wasn’t a lazy appropriation in the manner of the Police or the Rolling Stones, but something that drew on the spirit of the original to create its own surprising alchemy. It took a bolshie U.K. vernacular and married it to a cool Jamaican aesthetic. Punk was a cocktail slammer of shock, alienation, and spite, but such a hard-line aesthetic could last only so long. A new post-punk spirit opted to navigate other sound worlds. Name-dropping started to be far more inclusive: jazz, musique concrète, Africa, Germany, Jamaica. This new regime was far more polymorphously perverse, accommodating the noise-art experiments of the Pop Group, Wire, This Heat. Public Image Ltd put out a dub album of 12-inch singles. The Slits picked reggae maven Dennis Bovell to produce their debut album.

What gets left out of a lot of today’s cultural-nostalgia industry—“this classic album is thirty-seven years old today!”—is any acknowledgment of the often haphazard social forces behind things. Rachel does a great job conveying such collective endeavors and group dreaming, the whole circumference of people who support bands: friends of friends, drop-of-a-hat designers, stopgap agents, stall owners, dealers, grandparents with record collections, eccentrics without portfolios. In Too Much Too Young, Dammers recalls a “funny little old white lady that used to sell roots records. You’d go into her living room and she would have these U-Roy records. It was very strange.” Record shops were places to exchange information and convert people to your cause. People my age have vivid memories of places like Probe, in Liverpool (see Dave Haslam’s 2020 book Searching for Love), or Rock On and Rough Trade, in London. I have my own fond memories of certain long-ago reggae shops: the cloakroom-size emporium opposite the Finsbury Park tube station; Maroon’s Tunes, on Greek Street; Desmond’s Hip City, in Brixton. Such outfits were started by people who did it for both love and money, and were run by grudgingly helpful obsessives.

“The Specials,” by Chalkie Davies © The artist

A lot of British kids were having a bad enough time as it was and didn’t need a self-consciously depressive soundtrack. The Specials gave their young audience songs that chimed with their lives—songs about bad nights and wasted days, unemployment and daily brushes with the police—but that were delivered with rousing exuberance rather than weighty disaffection. Terry Hall’s voice was crucial; his vocals were often recorded in two separate takes, one bored and one angry, which were then mixed together. This may account for their nagging singularity, how they seem to perfectly embody the eternal small-town feeling of long stretches of boredom shattered by sudden outbreaks of violence.

The period 1979–80 saw the rise of both Margaret Thatcher and 2 Tone. The Specials’ debut single, “Gangsters,” reached number six on the U.K. singles chart in August, and one episode of Top of the Pops boasted a 2 Tone trifecta: the Specials, the Selecter, and Madness. On May Day 1980, Jerry Dammers was the cover star of the first issue of The Face magazine, a revolution in style to match a revolution in economics.

One of the ironies of the Thatcher era was that a lot of the oppositional counterculture ranged against her could be seen as a kind of ideal application of her own small-business dream: cottage industry get-up-and-go! (In Too Much Too Young, the Specials’ success is attributed to their “staunch work ethic.”) On May 4, 1979, the newly elected Thatcher stood on the steps of 10 Downing Street and solemnly intoned this now-famous speech, borrowing the words of St. Francis:

Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. Where there is error, may we bring truth. Where there is doubt, may we bring faith. And where there is despair, may we bring hope.

Which, in a spooky kind of way, exemplifies the Specials’ own mission.

“Black and white, unite and fight” was a popular slogan of the time, and Dammers talks of deliberately pursuing a “collectivist approach.” He goes on:

General ideas of justice and fairness and not wasting resources must have been influenced by my upbringing to some extent. . . . Politically, most of my influence would have come through the sixties: through Black music and rock music, which had a lot of political counterculture messages, and [the underground magazines] IT and Oz.

Traces of the hippie culture often derided by punks persisted in the form of the Arts Lab movement, as well as in alternative bookshops, distribution systems, performance spaces, and political collectives centered on health, sexuality, and legal aid. The Seventies are now routinely portrayed as a hellscape of bad weather, divisive strikes, and dilapidation—but I was there, and what I remember is that, compared with today, housing, public transportation, and higher education were all unbelievably cheap. Still, there were enough bad things. It’s difficult now—when we have multihued diversity as a matter of course—to recall just how hidebound the United Kingdom was in terms of public speech and representation: a true Little England of casual racism and sexism, where Saturday-night TV featured The Black and White Minstrel Show, and women were routinely dubbed “tarts,” “boilers,” and “scrubbers.” Regional voices or accents were depressingly anomalous in the public discourse of the time, with so-called Received Pronunciation the media norm. There was something genuinely political in the many voices unleashed by 2 Tone, including a very strong female roster: Pauline Black of the Selecter; the Bodysnatchers; Rhoda Dakar. In 1982, Dakar recorded a song with the Special AKA—an offshoot of the Specials’ original lineup—called “The Boiler,” whose depiction of rape retains its white-knuckle power and even today is omitted from most Specials compilations, even those that boast hardly uncontroversial tracks like “War Crimes” and “Racist Friend.”

It must be said that the Specials, although palpably on the side of the angels, were haunted by sections of their “rude boy” audience. Ska, like punk, attracted extremist elements looking for ultraviolence. The skinhead had always been a dangerously ambiguous figure, a lairy ghost at successive banquets, claimed and reclaimed time and again. As music merged with football, which then merged with far-right politics, it became increasingly hard to tell the nattily dressed angels from any regressive folk devils at large. Pauline Black remembers touring in the United States for the first time, and how “the Midwest was in a different century almost.” In one venue, the sharp-suited Selecter crew took to the stage after a wet–T-shirt contest, in front of an audience of stony-faced men in ten-gallon hats. Two tones indeed.

There’s a nice scene in the recent BBC drama series This Town—promoted as a kind of Specials origin myth–cum–melodrama—in which two characters arrange to meet in Coventry Cathedral because they know it’s the one place where they won’t be seen by anyone they know. Today, visitors to Coventry are just as likely to visit sites of Specials interest as they are St. Michael’s. The original 2 Tone office, at 51 Albany Road, now sports a commemorative plaque; the Coventry Music Museum features the 1961 Vauxhall Cresta—which, by law, we must now call iconic—featured in the Specials’ “Ghost Town” music video. This is all part of a wider post-Blair ethos whose response to terminally depressed communities is to attempt to “rebrand” them back to life, using history and culture as a shiny lure, overseen by the well-remunerated Kulturmenschen, brand managers, diversity bureaucrats, and government advisers. Cultural rebellion safe and snug now inside vitrines to take selfies by. Gift shops, tote bags, hashtags. There’s a creeping distrust of this kind of maneuver, in which past glory is used to cover present discontent. If there is nostalgia abroad, what is the nostalgia for, exactly?

The small Northern town where I live stages an annual reenactment of a battle in the English Civil War—a really great day, as it goes—but also pub nights themed around mod scooters and old Northern soul 45s. The live-music scene is wholly dominated by the regular visits of so-called tribute bands. (Anyone up for a night with mock Nirvana?) According to Bloomberg, three quarters of British nightclubs have shut their doors since 2005, and 35 percent of London’s music venues closed between 2007 and 2015; 13,800 nighttime businesses closed in the years from 2020 to 2023. Everything has gotten incrementally worse since COVID. Here is a world never to be curated in any culture hub: Boarded-up shops; an ocean of cheap booze and easily available drugs; inertia and inchoate dissatisfaction. Cities and towns haunted by ghosts of a “boomtown” past, yet unable to profit from today’s billionaire-led jamboree. The evaporation of hope in the Labour Party as a real political alternative. Massive resentment in the North about the collapse of the new HS2 rail project. A suffocating neoliberal “consensus” that represents no one’s views. A civic dialogue that seems fractured beyond repair.

One song that retains its power to articulate anxiety in the United Kingdom is the Specials’ “Ghost Town.” It seems to revive and rise from its vampire’s coffin any time the nation has a widespread crisis; it happened during the 2020 COVID lockdown, and I heard it again during 2024’s convulsive riots. People who weren’t alive when it originally came out now identify with its sharp-edged melancholy.

“Ghost Town” was released in June 1981, during a period of nationwide riots sparked by racial tension, stop-and-search police tactics (supported by the so-called sus law, which predominantly targeted young black men), and economic inequality. In 2002, Dammers recalled: “You travelled from town to town and what was happening was terrible. In Liverpool, all the shops were shuttered up, everything was closing down.” Cities like Liverpool, Glasgow, and Edinburgh were also early harbingers of an epidemic of cheap heroin that would reap so many living dead—and real corpses.

With mordant poetical irony, “Ghost Town” was both the Specials’ biggest hit and the last song recorded by the original lineup, which fell apart in huffy disarray even as the song was headed toward the top of the charts. Dammers would carry on as the leader of the Special AKA, best known for 1984’s “Nelson Mandela”; Terry Hall, Neville Staple, and Lynval Golding went on to form Fun Boy Three, and had half a dozen top-twenty hits. Fun, or the lack thereof, might have been the core problem. Dammers had become something of a Brian Wilson manqué, spending increasing amounts of time in the studio to sculpt the sounds he heard inside his head, provoking the exasperation of his idling group.

Like many songs hailed as much-loved classics, “Ghost Town” had a distinctly inauspicious release. The band didn’t like it, the band’s audience didn’t like it, even many in their hometown of Coventry didn’t like it. It was too glum. It was too preachy. It sounded weird, and you couldn’t dance to it! But Dammers knew that the most haunting music often sits right on the edge of corny muzak. (It’s no surprise that he later went on to assemble his own Sun Ra–themed jazz homage, the Spatial AKA Orchestra: utopian politics limned with a touch of uncanny retro kitsch.) “Ghost Town” is a beautifully constructed plaint, both mournful and life-affirming. Its double-faced nature is reflected in its two best-known performances: the official music video, which is downbeat and claustrophobic, and the band’s Top of the Pops appearance, which feels like a big kids’ birthday party. The song opens with a cold wind over a solemn New Orleans funeral beat and takes flight on a haunted ghost-train organ. On the sublime 12-inch version—dub itself being a kind of ghost music—Rico Rodriguez takes his long solo as if standing atop a prophet’s peak, overlooking a city in flames. The heart swells with joy, even as ashes swirl and collect.

What you notice now, listening to the Specials, is the number of lyrics about the past and the future, and how their brief moment in the sun sometimes seems to foretell our own present darkness. This, for instance, from “A Message to You Rudy”: “Stop your messing around / Better think of your future . . . ” It’s a line that goes against the grain of pop’s live-for-the-moment, eternally teenage ethos. Or, from 1984’s “War Crimes”: “From the graves of Belsen, where the innocent were burned / To the genocide in Beirut, Israel, was nothing learned? . . . / The numbers are different, the crime is still the same.”

And of all the things I’ve watched or read or heard lately, nothing has stayed with me like this one haunting line from the Specials’ first 45, “Gangsters”: “I dread to think what the future will bring / When we’re living in real gangster time . . . ”

Prophecy a fulfill, as the Rastas say.