The overpass where the Bundy family and their supporters confronted officers from the Bureau of Land Management, Bunkerville. All photographs from Nevada by Matt Black for Harper’s Magazine, 2024 © Matt Black/Magnum Photos.

The Great Basin is a vast interior watershed cut off from the sea and spanning some two hundred thousand square miles of the American West. Settlers traveling on emigrant trails largely raced through the region’s desert playas on their way to more productive lands in California and Oregon. When the frontier closed, much of the Great Basin remained unsettled, and the land ended up being administered by either the Forest Service or the Bureau of Land Management (BLM)—the latter being our national custodian of “the land nobody wanted,” as the old saying goes.

These are harsh places, with little to recommend them to the casual lover of nature. Under the principle known as multiple use, they are managed for the dual, and often hard-to-reconcile, purposes of natural conservation and the sustenance of human livelihoods. This is to say they get worked by people living in communities that tend to be of a conservative bent, meaning that they are full of people with recalcitrant attachments to rural ways of life, who live off the land, whether mining, ranching, or logging. And because these communities are surrounded by land managed by the federal government, with hardly any taxes to fund local services and few other options to sustain themselves besides the semiservile avenue of catering to tourists, they are highly dependent on decisions made in Washington.

You don’t need to know the impossibly complex history of regulatory squabbles and armed standoffs that took place in many of the locales seen in Matt Black’s photographs to sense how these conflicts linger today. The first image we see here is of the wash where, in 2014, the Bundy family and their allies confronted BLM law-enforcement officers who had rounded up some of the family’s cattle. On that day, gunmen had taken up positions on the I-15 overpass, ready to fire down at federal agents below. By any reasonable assessment, the Bundy family won that fight. Their cows were released, the BLM force retreated, and the Bundys won their eventual trial, one of the largest federal prosecutions in the history of the Western United States.

That conflict remains a particularly glaring piece of Western history, but almost every stretch of public ground in Black’s thermal photographs has its own record of conflict. Last summer, Black camped out of the back of a pickup and went to some of the most remote places in Nevada—more than 85 percent of whose land is federally owned—to take these images. His work involves prolonged exposures and the use of careful calibrations to capture wide ranges of surface temperatures. He shows us the hot points on the landscape, many of which are objects of human manufacture. Black offers us a guided panorama of the interactions between nature and industrial society that have shaped Nevada’s modern regulatory battles.

We see here two photographs taken in Jarbidge, Nevada, a town of only a few dozen people that became a national symbol of conflict in 2000, after the Forest Service halted road construction on a remote mountain in order to safeguard the habitat of the endangered bull trout, whose range includes the headwaters of the Jarbidge River. Hundreds of people arrived in town to protest the Forest Service’s decision. Calling themselves the Shovel Brigade, protesters assembled a caravan of school buses and headed into the mountains to rebuild the road themselves. To see or catch a bull trout in a place like the Jarbidge Wilderness can be a quasi-mystical experience. They are the most primordial-looking of all salmonids, and like any native fish in the isolated Great Basin, they are relics of an ancient time. But to eliminate road access to a wilderness area in a place like Jarbidge would have imperiled the town’s very existence. So a fight inevitably erupted.

In one of Black’s photos, we see an abandoned house in the lonely sagebrush steppe of northwestern Nevada, not far from the Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge, built to host pronghorn antelope and migratory birds—but which grew in the way that wildlife refuges in the West often have, by buying up ranches and pushing out, for the most part, the old economy that brought American settlers to the area in the first place.

Black’s thermal photography shows us, in a literal sense, the rising heat signature of our presence on public lands across the West. It has recently become common on the right to regard just about any government effort to regulate our use of these lands as the handiwork of an out-of-control bureaucracy bent on driving rural Western communities like Jarbidge out of existence. Meanwhile, it has become common on the left to assume that anyone who works on these lands cares for nothing other than extracting as much value from them as they can, as quickly as possible. Neither of these stories is fully false. Neither of them is fully true.

Things have gotten hotter and drier in these places. And the gulf between those on different sides of the regulatory debates has gotten wider. It’s going to be very tough in the coming years to maintain the spirit of multiple use, which, for all its faults, is one of America’s greatest political innovations. This system has allowed us to conserve a far greater portion of our national landscape than any hypercapitalist society might reasonably have been expected to. And yet the system’s detritus litters every corner of these public lands. Here, in images made more vivid and real for their absence of color, we see an exacting annotation of what our presence has wrought. We are left to stare closely and imagine what’s to come.

A disputed road, Jarbidge

A memorial to the Shovel Brigade, Jarbidge

A ranch fence, Fallon

An abandoned ranch house, Swedes Place

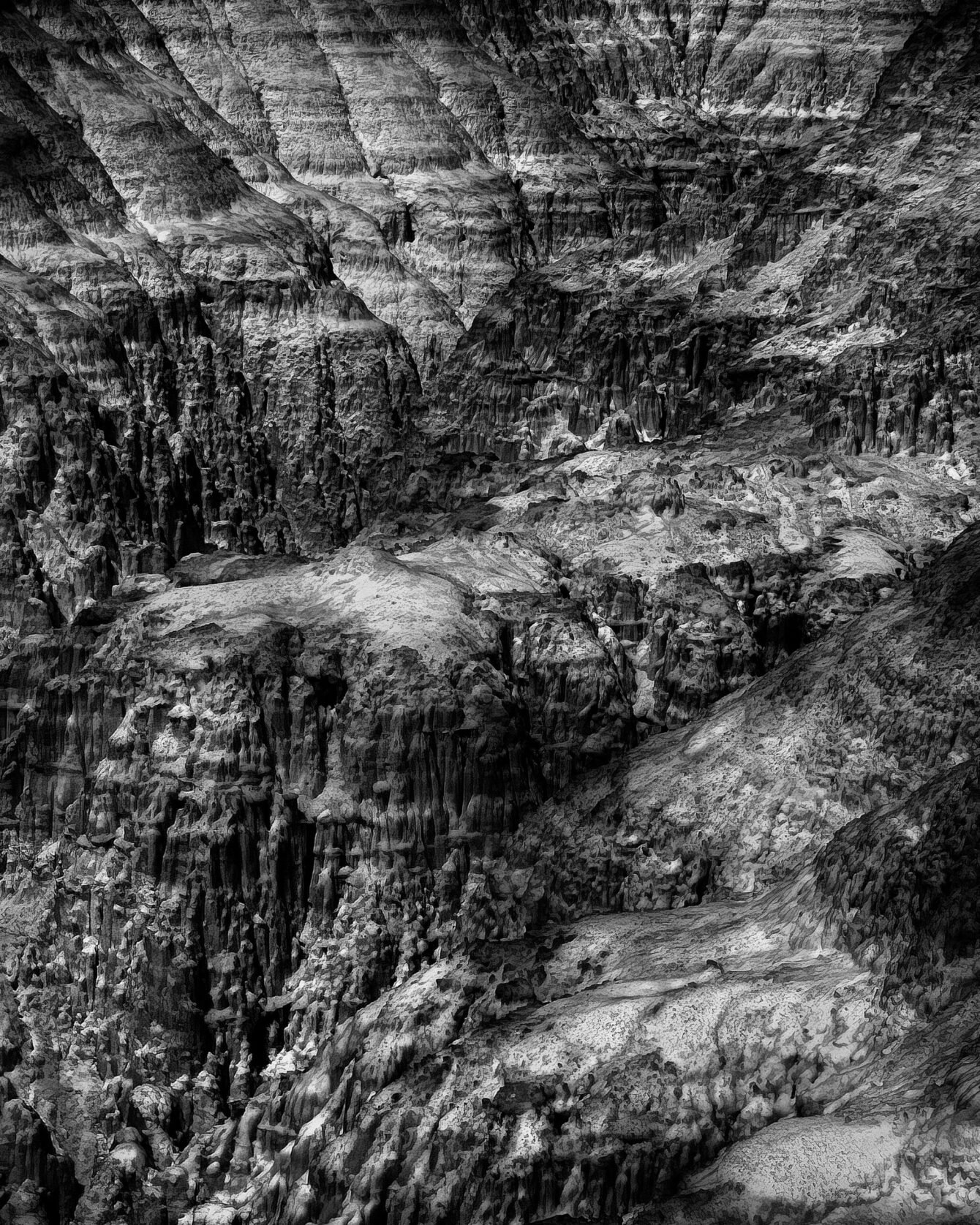

Cliffs, Panaca

Cacti, Gold Butte

A dead tree, Chimney Creek