When I began my tenure as publisher of Harper’s Magazine nearly thirty years ago, my biggest challenge — or so I thought at the time — was to get advertising agencies to pay more attention to the celebrated journal of American ideas and literature entrusted to my care. Harper’s had tens of thousands of loyal readers but not many loyal advertisers, so my task seemed clear. Fawning over salesmen rubbed against my political grain, but those days were dominated by the free-market dogma of the Reagan Administration, and I fell prey to some of the president’s most simpleminded thinking. If advertisers didn’t sufficiently admire serious readers of the Harper’s variety, then it was my job to persuade Madison Avenue and its clients that I was serious about their concerns — about selling their products to my readers.

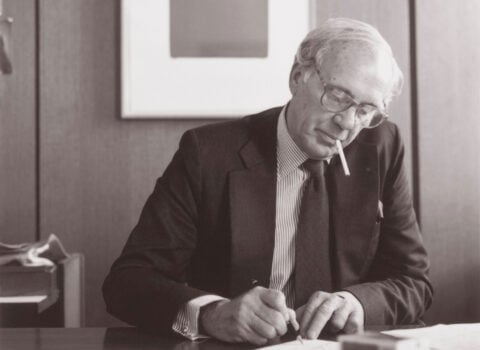

And oh how we sold! For twenty years, editor Lewis Lapham and I crisscrossed the country in pursuit of what everyone else in our business was after: glossy, high-profile consumer and corporate advertising. Armed with our good name — Harper’s, after all, was deeply enmeshed in America’s cultural and historical fabric — we maneuvered our way into company dining rooms from Wall Street to Rockefeller Center, from Louisville to St. Louis, from Boise to Palo Alto. We engaged our hosts in discussions of the political and literary issues of the day, but to better impress them we also invoked our affinity with the advertising world, presenting as evidence the brief stint on the Harper’s board of the legendary adman William J. Bernbach, as well as our own very slick house ad produced by the renowned firm of Scali, McCabe, Sloves. It didn’t hurt our cause that my late father, Roderick, was something of an advertising genius. I spoke the language of the advertising trade because, along with journalism and politics, I’d absorbed it nearly every day of my childhood at the kitchen table. It also didn’t hurt that Lewis Lapham and I were spawned by the very business establishment we criticized in nearly every issue of America’s oldest continuously published monthly.

Current readers may be surprised to learn that we were largely successful in our efforts: many corporations encouraged their ad agencies to take a fresh look at Harper’s Magazine, and the ads began to roll in. For my part, I was astonished that most of the CEOs we met, though nearly all Republicans, were barely ideological and almost never objected to the subversive, sometimes overtly anticapitalist articles that appeared in our pages. As our advertising revenue grew, I rarely worried about reprisals for anything we published. Indeed, one of the most stinging critiques I ever heard of George W. Bush’s disastrous invasion of Iraq came from the chairman of a major American oil company over lunch at his headquarters in Houston. For many of these men, and for their more liberal-minded advisers, Harper’s and its brand of open-minded, freewheeling discourse were automatically worthy of their backing.

But as the magazine’s bottom line improved through the dot-com boom that ended in 2000 and the anti-Bush boom that ended in 2009, something crucial seemed to be missing from our “marketing equation.” In all my scurrying back and forth between Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York, I never considered a fundamental question: Why did a magazine of ideas, criticism, and reporting need to serve as a sales medium between advertisers and readers; why should advertising be our principal means of support? Not that I didn’t want advertising or have respect for our advertisers, some of whom were genuinely civic-minded. But wasn’t the truly important compact — really the only relationship that mattered — between reader and writer or, to some extent, reader, writer, and editor? Harper’s is published first and foremost to be read. If the magazine functions as an intermediary, it is between the creative imagination of the fiction writer or essayist and the creative spirit of the sensitive reader; between the inquiring mind of the journalist and the engaged mind of the alert, occasionally outraged citizen. This compact now needs to be stated forcefully and in unmistakable terms.

As it happens, recent technology has brutally pressed my question about the appropriate connection between reader, writer, and advertiser on every publisher in our increasingly wired-up world. I was immediately suspicious of the Internet being touted, in the late 1990s, as a miraculously efficient publishing platform because of the Web’s capacity for massive copyright violation. But what disturbed me more as a publisher and a writer was the ugly commodification of writing itself — the renaming of prose and poetry as something called “content.” Suddenly, my colleagues and competitors were reducing well-wrought sentences and stories to the level of screws and bolts. Not only was “content” an empty and offensive word, but my fellow publishers also proposed to give it away free in the quest for more advertising. Instead of honoring the reader, writer, and editor, this new approach to the publishing business insulted them, both by devaluing their work and by feeding it — with little or no remuneration — to search engines, which in turn feed information to advertising agencies (and, as it turns out, the government).

The result, as anyone with even a passing interest can observe, has been catastrophic: massive layoffs of editorial employees; the collapse of major publications; the impoverishment of writers; the alarming decline of editorial standards for accuracy, grammar, and coherent thought; and the dumbing down of journalism across the board. Great American publishing institutions such as the Washington Post and the Boston Globe have been placed on the auction block for a fraction of their former value. Meanwhile, the advertisers themselves have fled traditional publications for the allegedly greener pastures of social media and Google. Paradoxically, the more advertisers demanded eyeballs and clicks, the more writing the publishers gave away, and the less advertisers advertised. We know what happens to lemmings — thanks to YouTube you can watch it in graphic detail any time of the day or night — so I decided early on I wouldn’t join in the frenzy of free content. From the launching of our website in 2003, we at Harper’s insisted that subscribers continue to pay to read our well-written, fact-checked, scrupulously edited, and extremely entertaining paragraphs. When the magazine became fully accessible online, our paywall remained firm. We are pleased to be able to offer the magazine in a digital format, but what we won’t do is give in to the free-content “logic” of so many publications. Tellingly, very few subscribers have complained, and we are still in business, having conceded nothing in the quality of our character or, dare I say, our content.

Paywalls are now being erected everywhere. Even the champion blogger Andrew Sullivan is asking his readers to pay twenty dollars a year for unlimited access to his work. But as with global warming, so much damage has already been done to the literary and journalistic atmosphere that I’m afraid we’re approaching a point of no return. I can’t quite believe my ears at the nonsense still being peddled by the advocates of free content. Who needs fact-checkers when we have crowdsourcing to correct the record? Why doesn’t Harper’s give away a particularly good investigative piece (such as Ted Conover’s powerful undercover report in May on an industrial slaughterhouse) so that more people will read it?

Because good publishing, good editing, and good writing cost money, and publishers, editors, and writers have to earn a living. We are proud that we can send a photographer to Iran for a couple of weeks and then deliver the resulting images to readers in our September issue through the mail on good paper and over the Internet in high resolution for computer screens and tablets. This photographer, who requested anonymity, risked arrest and prison to take excellent pictures — as do other photographers such as Samuel James — for the benefit of Harper’s and you. The censors in Tehran are surely upset. Shouldn’t Anonymous be paid for this courage and skill? Shouldn’t Harper’s be compensated for sending Anonymous into the field? All told, the photo essay cost us about $25,000, including printing, paper, and mailing. It is unreasonable to expect that an advertiser would directly sponsor such daring photography. It is wishful thinking to believe that parasitic Google, now bloated with billions of dollars’ worth of what I consider pirated property, will ever willingly pay Harper’s, or Anonymous, anything at all for the right to distribute Anonymous’s pictures (although it’s worth noting that the German government is fighting Google on behalf of German publishers and writers over this very point). We cannot even count on America’s enlightened public libraries to help foot the bill for Anonymous. I recently found myself in the Lenox, Massachusetts, public library, where Harper’s Magazine is currently unavailable. When our circulation director complained that the magazine that published Edith Wharton’s short stories, many written just down the road at the Mount, deserved pride of place in the library’s periodicals section, she was told that budget cuts had made it impossible for the library to pay for a subscription.

We, however, find it logical to trust that 150,000 discriminating Harper’s subscribers, tens of thousands of newsstand buyers, and thousands of on-screen readers will find it in their interest to pay substantially more for a magazine that publishes such outstanding material. This seems as evident to me today as my conceptually flawed advertising model did thirty years ago. And I’m beginning to sense a turning of the tide, in the quantity of new subscribers — many of them signing up through our website — and in the supportive emails and letters we receive every day that praise the careful editing and lively writing that go into every issue.

It has been a trying decade for publishers and writers all over the world, and our challenges can sometimes seem overwhelming. In the United States, unfortunately, the bankrupting of journalists and authors has been matched by an impoverished debate about how to sustain a high standard of publishing and writing. Until recently, the rush to appear modern, the peer pressure to accept the inevitability of print’s demise, and the supposed virtues of writing for free have dominated what passes for a discussion. “Is there a living to be made when editors expect to get quality, on-time copy for zero cents a word?” asked Mark Kingwell two months ago in these pages. Certainly not, unless we lower our standards and redefine the meaning of “good writing.”

Some voices of sanity, though, have been heard in Europe, in England most notably that of Tyler Brûlé, editor in chief of Monocle and Fast Lane columnist for the largely paywalled and still profitable Financial Times. More compelling still has been the experience of the French publisher Laurent Beccaria, founder of the book-publishing company Les Arènes and a quarterly general-interest magazine called XXI (“Vingt et un”). Together with his editor, Patrick de Saint-Exupéry, Beccaria has defied the conventional wisdom about the free-content model and turned XXI into the most dynamic, and perhaps the most profitable, new magazine on the European scene. Although it does have a website, you cannot read XXI on a computer — you must buy the print edition for the equivalent of about twenty dollars a copy at a bookstore or get it through the mail. The quality of XXI is guaranteed not by fickle marketers suffering from short attention spans but by faithful readers whose powers of concentration — whose appreciation for the elegant sentence and the hard-earned insight — have survived the onslaught of the Web’s unedited mediocrity.

This January, Beccaria and Saint-Exupéry published a manifesto in XXI that sought to reclaim the journalistic territory conceded too easily to online, unpaid, snippet journalism. We’ve published an excerpt in this month’s Readings section that I believe speaks for itself; I urge you to read it. Beccaria and Saint-Exupéry offer many smart observations, but this one seems paramount for my purposes and for the continued health of Harper’s Magazine:

Pompous phrases about the need “to reinvent the press’s economic model” mask the reality: what has to be restored is the exchange value between news publications and their readers. How many of us would agree to spend two or three dollars for an espresso downed in five minutes but would balk at forking over the same for a daily or weekly news organ as these are currently conceived? To be useful, desirable, and necessary — that’s the only economic model worth considering. It’s as old as the world, as old as commerce.

Thus shall we proceed — in partnership with advertisers who recognize the profit in being associated with a magazine of the highest editorial standards and with our extraordinary, paying readers. We are investing heavily in reporting and photojournalism, consistently running more pages than we have in decades. Along the way I’ve learned that to be “useful, desirable, and necessary” is to serve the reader and the writer, not the Internet, or the consumer, or the lords of merchandising. Harper’s Magazine is not a cutting board for sausages sold at a certain cost per thousand. It is, among other things, what the late New York senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan called “the fulcrum of American letters and public comment.” It is a storehouse of the American experience dating back 163 years, including much of the country’s greatest belles-lettres, journalism, and, increasingly, art and photography. At our best, we provoke that “zig-zag streak of lightning through the brain” (a phrase of Edward Grey’s quoted by Lord Asquith to describe Winston Churchill) when a reader’s mind is pierced by an understanding or a realization that was previously inaccessible.

But Harper’s is also an agreement between reader, writer, and publisher to reject spoon-fed, tailored solutions — and that goes for the Internet publishing model as much as it goes for invading Iraq, democratizing Afghanistan, and protecting the American population from terrorists by warrantless spying on every last one of us. With your support, we’ll do better than just survive; we’ll help bring the national conversation back to a level of intelligence, comprehension, and authenticity that will make our readers and contributors proud. A literary and political conversation, I hope, in the spirit of the great editor Maxwell Perkins, who, feeling pressured to make Ernest Hemingway conform to the short-term exigencies and whims of the marketplace, wrote to the author in 1935: “All You have to do is to follow your own judgment, or instinct, + disregard what is said, + convey the absolute bottom quality of each person, situation + thing. . . . I can get pretty depressed but even at worst I still believe — + its written in all the past — that the utterly real thing in writing is the only thing that counts, + the whole racket melts down before it.”