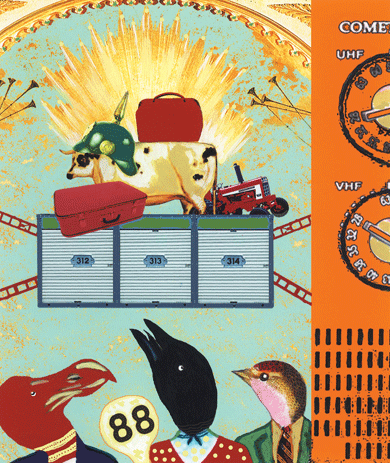

Every day, all across the country, people travel near and far to assess exteriors — of homes and luggage and corrugated-iron cubes — and fantasize about what might be, but probably isn’t, inside. Then they bid at auction so that maybe, just maybe, they’ll get more than their money’s worth. There are television shows that purport to document this suspense — of the cautious turned lucky and the confident crushed. Sorry characters compete against one another for the privilege of owning abandoned property they know nothing about: houses with nonexistent plumbing, suitcases more likely to contain spilled toiletries than precious jewels, storage units stuffed with junk.

Storage Wars (A&E), Auction Hunters (Spike), Baggage Battles (Travel Channel), and Property Wars (Discovery Channel), all of which have premiered in the past four years, use the competition of the auction as a plot device for exaggerating their characters’ eccentricities and activating the audience’s schadenfreude. Dubious windfalls keep things from becoming monotonous. Bags forgotten at airports turn out to hold not just cotton sportswear and travel-size bottles of facial cleanser but also pocket watches and rare coins. We learn that vintage electroshock-therapy machines and nineteenth-century replicas of Czechoslovakian mechanical toy banks are “worth a lot.” Dinky fixer-uppers are fitted with Sub-Zero refrigerators. McMansions, still stinking of new vinyl siding, can be pristine — Italian marble, Jacuzzis, stainless-steel appliances — but at least as often they are empty: plastic shells abandoned in the desert.

These auction reality shows — a genre referred to by TV producers as “found money” — make no pedagogical promises; we are in the presence not of specialists but of autodidactic dreamers. The swagger of the cast betrays a kind of scrambling naïveté. Episodic catharsis relies on the expertise of appraisers, brought in to affirm or snuff out unfounded hopes. It takes two people to set a price, and auctions are where one sees firsthand the cruel, stark truth of the world — that an unwanted thing is literally worthless.

To enjoy such shows, one must ignore the likely backstories — the bankruptcies, divorces, foreclosures, and deaths that thrust these lots onto the auction block — and attend instead to the petty exuberance of the plot, to the bidding and yelling and triumphant cries of victory. “Shock & Awe,” the fourteenth episode of the second season of Baggage Battles, is set in Benton, Louisiana, a town that our protagonist, Billy Leroy, claims, falsely, is “not on Google Maps.” Billy, along with the show’s other regulars, has traveled here to attend an auction being held in a barn. He arrives in a vest adorned with watch chains and rummages through some dusty piles of rusted miscellany while smoking a cigar. Finally, he zeroes in on two desirable items: a “very interesting, beautiful” wooden box and a military trunk. The latter, he wagers, could be full of swords, guns, helmets, and uniforms. Billy “just has a feeling” about the box, and inside the trunk he hopes to find a piece that will allow him to retire early.

Mark, the show’s youngest regular, confirms Billy’s logic: “If it’s a well-crafted box, it generally contains something great.” Mark and Billy bid against each other, and Billy eventually wins the thing for $200. It turns out to be an antiquated polygraph machine. Both men are dismayed to learn that the other auction attendees are most excited about bidding on some unopened bags of manure.

Billy totes his haul to the car and finally peeks inside the military trunk. At first, it appears to be filled entirely with magazines, but under a few layers of decaying paper is another box — a box within a box! Nested inside this box is an antique optometry kit used by traveling eye doctors who went farm to farm administering exams. Unexpected? Yes. Interesting? Reasonably. Valuable? No. But Billy seems thrilled, and brags to the camera that it’s worth $350. As is usual with this kind of show, we never get to see whether Billy is able to resell the item for that price.

Despite the repugnant personalities and dismal quality of the goods in question, the found-money shows, with their blustering titles and cheap production values, can tell us something about the American economy. Television producers have taken a staple of no-nonsense markets — put a thing on a stage, allow people to view it with their own eyes, and force them to price it among themselves — and made it about surprise and obfuscation. The price that Billy pays for the optometry kit is a function not of the thing’s value (clearly — who would want one of those?) but of his confidence in his own luck. The auction, in this light, becomes a venue for blind speculation. What was once an occasion for pragmatic decision-making is now a lottery played by hopeful fools.

I have spent my entire adult existence in a recession. The stock market crashed when I was a senior in college. I belong to a microgeneration whose moneymaking life has taken place in a pessimistic, alarmist era strewn with the detritus of failed, deliberately convoluted financial instruments. Like most people I talk to, I assume the forces that control the market are at best random and at worst rigged. The rules seem vague and tractable, the system obscure and sinister. We worry that nobody really knows what they’re doing.

The auction shows only confirm that suspicion. But I know there is, somewhere, the mirror image of the financial world of Wall Street and televised treasure hunts. Cattle auctions, for example, are held in Crockett, Texas, every Tuesday at noon. In April of last year, I went there.

When I arrive at East Texas Livestock, the parking lot is full. The odor of steer manure is at first off-putting and then suddenly hypnotic, and I find myself leaning on my rental car for almost a full minute, trying to somehow smell beyond the scent. The moos, the hundreds and hundreds of moos, are drawling and deep and relentless.

A bench lines one wall of the wood-paneled entrance hall, and above it hangs a cluttered bulletin board. The bulletin boards near my apartment in Brooklyn are plastered with flyers for specialty services: SAT tutoring, yoga lessons, yoga lessons for babies. Here, the flyers advertise stuff: firewood, golf carts, backhoes. It all seems reasonably priced. Across the room are two windows, one marked buyers, the other sellers. A secretary, taking either interest or pity, beckons me inside.

Four women sit at desks, typing on outdated computers and making piles of the paper tickets they pluck from a pneumatic-tube system. One complains about a fresh sunburn; another is worried that she might get fined for having a bouquet of bluebonnets on her desk. (Bluebonnets are the Texas state flower. It’s commonly believed that it’s against the law to pick them, but it’s not.) I say I’m here to talk to Paul Craycraft, and I’m instructed to wait for him on the office sofa.

Craycraft, who is in his early sixties, owns East Texas Livestock with his brother, Ray. I do not meet Ray, but I imagine him looking just like Craycraft, which is to say tall, handsome, and weathered — the patriarch in a Ralph Lauren ad. Craycraft saunters into the office wearing a straw hat, a madras shirt, Wranglers, and a pair of shit-caked cowboy boots. “Nice to meet you, ma’am,” he says, shaking my hand firmly. I beam. I have never been called ma’am before. In his other hand Craycraft is holding a cattle prod.

We make our way across a catwalk erected above the open-air maze of pens. The chorus of richly layered lowing is psychedelically loud, and the cows themselves are more beautiful than I thought they would be. Their eyes are wet and clear, and their plastic guitar-pick tags dangle like earrings. “If you were here in 2011, for the drought, you would have seen some real skinny cows,” Craycraft says glumly as he walks ahead of me. These cows seem pretty robust, not that I would know. Mangy dogs run around barking, their fur matted with what looks like egg yolk.

Down the stairs and into a pen we go. A bucket of yellow paint stands open and oozing on the ground. (This explains the yellow dogs.) Hanging from a nearby table are metal rods ending in paint-covered metal digits. Craycraft explains that the rods are dipped in paint and stamped on the cows’ hides to indicate their age and, when appropriate, how many months pregnant they are.

Here, in the pungent shade, sits a collection of gleefully filthy men: a veterinarian, his assistant, two beef producers from Beaumont, and an ag teacher turned preacher whom Craycraft has not seen since 1981.

As Craycraft and the preacher catch up, George Beeler, the vet, offers to demonstrate how cows are aged. What sounds like a harmless enough chore turns out to be a fairly nightmarish undertaking — for the animals, at least. The cows are funneled one by one through a narrow chute, appropriately called a crush. It ends in a steel cage with an opening for the head. One cow, drooling and wild-eyed at this point, attempts to escape. No go. Once she calms down a little, Beeler peels her lips apart to reveal a mouth that looks unsettlingly like a human’s, and proceeds to count teeth: cows grow a new set of permanent incisors for each of the years between ages two and five; after that, though, the ages are estimates made on the basis of tooth wear. Most of the cows here today are just shy of a decade old. They’re “short-solids,” meaning their teeth are worn but in good condition. “If they’ve eaten rocks or sand, they get ground down pretty quick,” Beeler points out, finger on an incisor.

Looking inside the cow’s mouth — a view that any bidder so inclined is privy to as well — I’m transported away from the animals and their dung. I can’t help but think of my television screen: of all those metal storage lockers with the padlocked doors and mysterious contents; of the mansions in Arizona with God knows what inside. We’re allowed an intimate inspection — count teeth, examine tongues, thumb those velveteen nostrils. A cattle auction is about knowing you need something and buying the best/cheapest version of it. A cattle auction can be a social occasion, but it’s not about surprise.

My sandals grow tight with drying manure, and flies swarm in the crooks of my elbows. The sundress I’m wearing has wilted in the humidity, much of which is probably my own sweat. It’s time to move indoors.

The auctioneer’s chant is audible in the hallway, but not until the doors are opened does the noise take on its proper stentorian weirdness. The bouncy, singsong prattle is punctuated every twenty seconds or so with an identifiable English word. The auctioneer, a strapping young man named Jake Jacobs, is stationed on a small corner dais.

Jacobs’s father was also a cattle auctioneer. “I was bred into it,” he tells me later. (This belief is not uncommon. When Jones’ National School of Auctioneering and Oratory was founded in Davenport, Iowa, in 1905, most auctioneers viewed it as a scam; the skill was hereditary, not something that could be taught in a class.) Jacobs’s patter is exceptionally fast. I stand in the entryway stunned for a moment, then slip in and quietly find a seat on one of the few open benches in the amphitheater. The room is filled with cattle raisers and order buyers. (The sellers for the most part stay home.) The cattle raisers wear gray janitorial coveralls; the order buyers sport starched shirts and creased blue jeans.

Brandon Gresham is a third-generation order buyer. It takes a few smiles and some friendly body language on my part to get him to tell me this. He travels throughout Texas attending auctions and buying slaughter cows according to what his company needs on a given day. “Packing plants know what they want,” he says. “Some want lean, some want fat.” A “high-yielder” is a cow that produces lots of flesh for comparatively little work. Too scrawny and you won’t get much meat; too fat and you’ll spend a lot of time dealing with the carcass. High-yielders, of course, fetch the highest prices. Gresham comes to auction with a list of quotas (such-and-such number of cows at such-and-such weight), and once it’s checked off, he’s out. “Hamburger meat in the morning,” he says, and walks off.

The cattle raisers, on the other hand, buy stocker cattle, cows and weaned calves ready to be fattened up. They will be transported to pastures, where they will graze for at least three months, and then on to feedlots, where they will eat mainly corn to gain weight just before slaughter.

The guy behind me, a cattle raiser if ever there was one, places his feet on the back of the seat next to me. His shoes are off. The gesture could be unconscious, aggressive, or flirtatious. All options seem equally likely.

The cows are ushered through a little door on the left-hand side of the stage by a guy holding what looks like a cross between an oversize flyswatter and an oar: a livestock-grade taser. Every time an animal takes too long to come in, it’s given a firm zap. The cows run across the stage one at a time, sometimes spinning frantically in a circle. Seldom does any single cow spend more than thirty seconds on display before being led back out, heart-wrenchingly oblivious to the fact that she is now the property of an entirely new owner. When a mother-calf pair is up for sale, there’s a bit more commotion, and the transaction takes a few seconds longer. After they are sold, the calf scampers after its mother with an awkward delay, like a teenager following a more popular friend around a party.

The price range for a stocker cow ($1,100 to $1,800) reflects a lot of other prices — the price of hay, the price of fuel, the price of corn — as well as the individual cow’s attributes: age, reproductive capabilities, feed conversion (i.e., how fat it can get off how little food). A cattle auction is not a very telegenic event. Each cow is sold too quickly, and they all look the same. There are no rookies here, no men who don’t know exactly what they are doing, no buyer’s remorse. Nobody to admire, nobody to pity. Appraisers are not consulted after the sale for reassurance; ego is not a metric.

But the frenetic pageant is hard to look away from, and it’s easy to forget that the seemingly lethargic audience is made up of shrewd businessmen. Jacobs, of course, never forgets these people; throughout his entire babbling monologue he is also scanning the audience, taking stock of micromovements that even I, with no other obligations, cannot catch. The bidders came not with numbered paddles, but with personalized gestures of assertion — a clipped “hey,” a twitch of the shoulder. Jacobs refers to bidders by name.

Sitting here, in this echoing vault of capitalism, I am less confused about the price of a good than I’ve ever been. And while I’m reluctant to glorify the dignity of manual labor, romanticize agrarian enterprise, or oversimplify a dense matrix of activity, the whole operation seems refreshingly straightforward. It makes me wonder whether the much-maligned, all-purpose nostalgia that’s rampant among city-dwelling young adults — the pickles, the flannel, the rye-based cocktails — is really a kind of mass intellectual crisis: an allergy to economic abstraction.

I go outside into the blinding heat and find a man named George Whittlesey, who comes here every Tuesday just to see what’s up. “The market’s higher than it’s ever been,” he says. “There’s a shortage of cows, because of the drought.” The recent drought, I learn, has culled East Texas herds by about 40 percent. Whittlesey’s son used to “cowboy everyday,” which means he worked as a contracted day laborer on ranches from Beaumont to Buffalo. Now he works at a bank. This bit of family information is presented with minimal pathos.

Unlike a hedge-fund manager, who is aware of but cannot see the forces affecting his success — “confidence” in Western Europe, “social innovation” in China — the cattle farmer can trace the causes of his economic circumstances; they are self-evident. If raising cattle is, as one woman told me, “a dying life,” maybe this is why. If given the choice between a life dictated by the weather and a life dictated by abstractions, maybe young adults in Texas today — unlike my neighbors in Brooklyn — would choose the latter. Maybe they’d rather just not know. As Craycraft tells me, “The kids don’t come back here. They don’t want their lives determined by the elements.”

Ritchie Bros., a publicly traded company headquartered in Vancouver, is one of the largest auctioneering companies in the world. They hold no-reserve auctions of industrial equipment in forty-four locations worldwide, including Beijing, Brisbane, Dubai, and Toronto. In 2009, Ritchie Bros. relocated their Houston operation to a 130-acre plot visible from the intersecting lanes of Interstate 69 and the Sam Houston Parkway. An aerial shot of the site would reveal a quiltlike pattern of gray and yellow and green. Gray for the cement. Yellow and green for the Cats and John Deeres, of which there are hundreds. Crockett smelled like manure; the Ritchie Bros. auction site smells like diesel and burning rubber.

The Ritchie Bros. auditorium has polished concrete floors and fluorescent spot lighting. The rows and rows of orange plastic seats contain a sea of massive men, all in exotic-hide cowboy boots and promotional T-shirts — for contracting companies or equipment manufacturers or the band Kiss. They’re equipment resellers and brokers and fleet managers. They look like monster-truck-rally fans, but are, in the words of Ritchie Bros. CEO Peter Blake, “probably wealthier than people you’ll meet walking down Park Avenue in New York.”

The audience faces a glass wall, behind which equipment — tractor-trailers, barrel-bottom frac tanks, hydraulic excavators, crawler cranes — is driven across a narrow concrete runway. It’s like a procession of what clutters a boy’s bedroom floor, only much, much bigger. Bid catchers — the men who act as the auctioneer’s eyes to spot the subtle tremors and spastic yelps of bidders — stand at the front of the room. Their stances are heavy and their spines tilt slightly forward, as though they’re getting ready to take a punch. They make gestures probably learned from football coaches — urgent “c’mere”s and that thing where you point to a person with one finger and then back at your own eyes with two. A fleeting loyalty develops between individual bid catchers and individual bidders, a sense of camaraderie that vanishes forty seconds later when it’s time for the next lot.

More than 1,500 bidders are registered on-site the day I visit, joined by 2,000 Internet bidders from about fifty countries. The equipment is movable; it goes where it’s needed. The value of an individual item is driven not so much by whether it’s sold in Houston or San Diego or Montreal but by the condition it’s in and the prevailing need for it in the global market. “The world market will tell you what something’s worth, and that’s the price,” says Peter Blake.

Today’s auction begins at eight in the morning and lasts until late in the afternoon. Over the course of these nine-plus hours, men will wander in and out of the auditorium, spending a good amount of the day outdoors, surveying pieces of equipment they might or might not buy. The pieces on display — cranes like apatosauruses, tractors the height of basketball hoops — make these men look tiny. This is probably the only place on earth with this effect.

Among the people I meet are a Bolivian machinery exporter who triples as a professor of public policy and a newspaper columnist, a twenty-one-year-old woman looking to buy a truck that she can sell flowers and teddy bears out of come Mother’s Day, an industrial-steel contractor originally from England who wants a “piece-of-crap water truck” to use on his ranch, the chatty president of a company that procures specialized pipeline equipment, and the laconic president of an equipment-resale business who comes to every single Ritchie Bros. auction in the state.

Romeo Rendon is the man I talk to most extensively. Rendon is almost fifty, the founder of a company that delivers truckloads of pulverized rock to the newly discovered oil fields south of San Antonio. He grew up in a border town, selling machinery to buyers in Mexico, just like his father, who came to these auctions since before there was a temperature-controlled site with refreshment kiosks, back when it was just a cluster of folding chairs in a tent. Rendon is here today in hopes of getting a good deal on lot 1741, a 2002 Freightliner Columbia Sleeper Trucker Tractor. This requires him to perform all sorts of perfunctory inspections — of blowback force, of engine condition, of gauge function. He looks for equipment consigned by large companies — identifiable by the logos still emblazoned on the sides — because there’s a better chance they’ll be well maintained. “Mom-and-pop operations run their machinery into the ground,” he says.

Approximately 70 percent of Ritchie Bros. buyers are end users, guys who basically sit in machinery all day long. It makes sense that the best way to evaluate an item is in person — turning on the engine, listening, watching it smoke; testing the hydraulics and the brakes; scooting the thing back and forth.

Eventually I make my way to a glassed-off little chamber, a place with good acoustics and a view of the entire floor. It’s in there that I meet an eager young banker from San Antonio who after roughly thirty-five minutes of rapid-fire monologue becomes panic-stricken and pleads with me not to use his name.

S. is twinkly-eyed, mustachioed, and heavyset in that superficial way where if one were to transport him out of Texas for, say, six weeks, he’d lose a quarter of his body weight easily and unintentionally. It’s like he has a subcutaneous layer of culturally prescribed bad decisions insulating him: drinking sweet tea instead of water, taking rides in golf carts instead of walking, eating portions of red meat larger than his head.

For the past three months, S. has been on a wild ride. These ninety days are the reason he’s at the Ritchie Bros. auction, and also why he regrets talking to me so candidly. Briefly: S. has been driving around South Texas; he’s been collecting and marshaling equipment from a bankrupt client — a company, not an individual. S. was sent by his boss to repossess it. He tells me about the adventure, hinting at multiple episodes of violence and heavy drinking.

S. begins in a soft voice, so as not to distract the auctioneer, but as his tale progresses his voice gets louder and louder, until he’s talking at a completely normal, maybe even loud, level. The auctioneer, who is perched on a swivel stool and allowing his foot to vibrate at a superhuman frequency, finishes a round — a Caterpillar D9L crawler tractor to an online bidder in Djibouti — whips his head around, and tells us to shush. We do. He resumes crying the lots, but his babble soon changes. It’s even odder now, and less comprehensible. I can’t figure out what’s going on. A nearby Ritchie Bros. employee registers my confusion and explains that the auctioneer has switched into Spanish for the sake of a Mexican high bidder.

Next up is the series of items consigned by the bank where S. works; this is the moment he’s been waiting for. I follow S.’s gaze and stare expectantly at the ramp. A dozer rolls by. S. grins. Bidding is frantic, and the piece sells for $125,000. “We pulled that thing out of a pit in South Texas,” S. says, still smiling. “It looked like it had been through hell and back, and now it’s going to Australia.”

American manufacturing equipment, bought against bad credit, is seized and sold to an international buyer who will use it to develop property abroad — of all the things I hear at the auction, S.’s story is the only one that reminds me of the mess we’re in.

Over the years, television networks have approached Ritchie Bros. about the possibility of featuring their sales on a show. The charismatic auctioneers, the colorful equipment, the near-parodic masculinity of the events: in the hands of the right producer, it could make for great TV. But until last spring Ritchie Bros. had always refused. What persuaded them was a “very fly-on-the-wall, interview-style” approach, according to Kim Schultz, their corporate-communications manager. That meant no contrived dramas, no make-believe feuds. The show, called Selling Big, was set at the company’s Edmonton auction site. Compared with the found-money shows it was pretty tedious.

Pat Hicks, one of the regular criers at Ritchie Bros. in Houston, tells me about Gallery 63, an auction house outside Atlanta specializing in expensive, esoteric items such as meteorites and vampire-hunting kits. Gallery 63 is the focus of Discovery’s Auction Kings, and Hicks has heard rumors that its employees are forced by the show’s producers to sign agreements saying they’ll rig the sales for the sake of plot.

That the found-money shows stretch the truth for entertainment value is not surprising. When I call Daniel Schwartz, an executive producer of Baggage Battles, he’s excited to tell me about some recently discovered auction items — an astronaut’s helmet accompanied by an instructional manual explaining how to pee in space; a gold-plated, life-size statue of Jennifer Lopez seized from the leader of a Mexican cartel — but he is totally unabashed about the rarity of such items. “We don’t show you everything they bought,” he says. “ ‘Oh, please,’ someone will say. ‘He really found a Playboy Bunny outfit in mint condition in a hat box?’ Well, we didn’t show you the other ten things he bought. Less than ten percent of what these people buy makes it onto the show. They’ll come up saying, ‘I’ve got nothing.’ But that’s life.”

Larry Hochberg, the executive producer of Property Wars, worries that found money might be on its way out, that as the economy improves, viewers will be less inclined to, as he says, “get the thrill of seeing someone make something from nothing, that comeback feeling.” Hochberg predicts that we’ll soon be seeing the resurgence of a different sort of wish-fulfillment reality television, the kind centered on “what people like to see when they’re financially better off.” I think back to the shows I watched pre-crash, the ones devoted to delusional and prohibitively expensive makeovers (The Swan) and orgies of conspicuous consumption (My Super Sweet 16). Hochberg tells me about a new series on Destination America called King of Thrones, which focuses on opulent and outlandish bathroom remodels involving things like flatscreen televisions and solid-gold urinals. “I see something like that,” says Hochberg, “and I think, ‘The pendulum must be swinging the other way.’ ”

When asked about his own attraction to Property Wars, Hochberg is surprisingly frank. “It’s a little bit disturbing,” he says. “It’s fascinating to see people get so excited about what’s in that box when they know nothing about what’s in that box.”

What-you-see-is-what-you-get-style auctions like the ones I witnessed in Houston and Crockett might make for bad television — their entire point, after all, is that bidders experience no “reveal” — but I wonder, as we leave the Great Recession behind, whether viewers would perhaps appreciate seeing common sense at play. Maybe there would be something inspiring about seeing expertise and rational pricing in action. But probably not, which is why I’m not a reality-television producer and this past recession won’t be our last.