When I arrived in Cairo in the fall of last year, my thoughts kept turning to the bloody events of the summer that had just passed. By then, most of the leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood — the eighty-six-year-old Islamist organization long persecuted by successive Egyptian regimes — were either in jail or in hiding. Mohamed Morsi, the Brotherhood-backed president dramatically ousted after only a year in office, was in detention, facing sundry charges ranging from espionage to incitement to murder to misappropriation of state funds ($460,000 allegedly spent on “ducks, chicken, and grilled meat”). At the airport, a long-faced taxi driver offered me a limp thumbs-up when I inquired about the state of things. “Very good,” he said in a monotone. “Very calm.” And yet this calm struck me as an eerie one. Boxy military tanks and trucks were everywhere, poised as sentinels at major intersections, at the mouth of every bridge, and along the manicured road to and from the airport. The generals in charge had declared a countrywide state of emergency and imposed a nightly curfew — a hallucinatory measure for Egyptians, who are night owls. There were terrible stories about what happened to people who stayed out too late, like that of an unlucky Frenchman arrested and beaten to death in his jail cell.

Supporters of General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi gather in Cairo’s Tahrir Square after an announcement by Egypt’s electoral commission naming Sisi the country’s new president, June 3, 2014 © Ahmed Ismail/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

During those strange, abbreviated days, the margins and marginalia of the local papers revealed a great deal about the state of the national psyche. There were, for example, an unusual number of ads for online courses in anger management. Notices for jobs in prosperous Gulf cities like Dubai, Doha, and Abu Dhabi. On the website of Al-Ahram, Egypt’s state-run newspaper, a message would pop up: “Learn the four signs of heart attack.” In October, an article in the same paper announced that a huge shipment of counterfeit Xanax had been successfully intercepted. There were runs on Xanax throughout the country. Antidepressants and painkillers also.

Egyptian antiquities were in a sorry state. King Tut’s sister had gone missing, a limestone figure of the princess from the fourteenth century b.c. swiped from a small museum in Upper Egypt by godless looters. In rural China, the entrepreneurs behind a new theme park had erected an exact replica of the Sphinx — same girth, same phantom nose — prompting Egypt’s minister of antiquities to angrily file a complaint with UNESCO. The tourists who had for decades flocked to Egypt for a sight of the actual Sphinx were no longer coming. In 2010, 361,000 Americans visited Egypt. In 2013 that number was, according to the minister of tourism, “closer to zero.” Egypt has lost 3,000 of its millionaires to emigration since the reign of Hosni Mubarak, the dictator ousted in February 2011 after thirty years in office. It has also been declared the worst place to live on earth for expatriates. Another poll — no relation to the former — concluded it was the worst Arab country for women. According to the country’s interior ministry, homicide rates have tripled since 2011. Abductions have risen fourfold, armed robberies by a factor of fourteen.

With Morsi locked up, an interim government was in place, and yet no one, including my taxi driver, could tell me the name of the new prime minister. Influxes of cash from the Saudis, the Kuwaitis, and the Emiratis — regimes with a history of animosity toward the Muslim Brotherhood — led the state press to spin tales about how life had magically improved in post-Morsi Egypt: gas-station lines were shorter, electricity was more reliable, the perennially crusty Nile was newly sparkly. Almost no one wanted to talk about what had happened over the summer. Conversations I had in the following weeks often ended in uncomfortable silence or a gentleman’s agreement not to talk about politics.

Looking at this grim picture, one might begin to understand the spectacular rise of a man named Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, a career military officer and former minister of defense who, as Egypt’s new president, is perhaps best known for his ability to excite large numbers of women. And yet, Sisi has presided over a political change of surreal proportions: in three years, Egypt has swung from a poster-child revolutionary state to a polarized military dictatorship whose oppression surpasses even that of the Mubarak era. How did a happy story about an emerging democracy become a familiar one about grinding dictatorship — and dictatorship with the mandate of the people, no less?

If Tunisia is where the Arab Spring began, Egypt seems poised to become its burial ground.

President Mohamed Mohamed Morsi Isa al-Ayyat: it still sounds unbelievable. Just over a year ago, a member of the decades-banned Muslim Brotherhood was the leader of all Egyptians, sleeping in the same Persian-carpeted palace Mubarak and the wife he affectionately referred to as Suzy once roamed. This was what the telegenic 2011 revolution had wrought: one man, one vote. The people had spoken, though Morsi’s detractors would point out that he had won by a hair (51.7 percent of the vote). Morsi’s political missteps soon began piling up. The new president issued an extra-constitutional decree that gave him sweeping powers even his predecessor hadn’t had. He bungled the economy in the name of a vaguely defined “Renaissance Project.” He alienated potential political allies — the judiciary, the police, the army — by favoring members of the Brotherhood in his political dealings. He green-lighted a constitution drafted by a Brotherhood-dominated parliament that failed to adequately protect the rights of women and minorities. When things went wrong, he blamed the felool, the dregs of the former regime. He also irked many with his uncouth behavior: when he met his Australian counterpart — a lady — he adjusted his balls on camera. It was not uncommon for people to refer to him as a monkey.

There were wild rumors about his plans for the three remaining years promised him: annex the Gaza Strip, blow up the Sphinx, ban the ballet (because of all the erotic costumery). A breaking point came in June 2013, when he appointed as governor of Luxor a former member of al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya, an Islamist group responsible for killing fifty-eight tourists and four Egyptians in an attack on the Temple of Hatshepsut in 1997. The appointment roused fears that the Brotherhood’s commitment to nonviolence was insincere (the organization officially renounced political violence in the Forties).

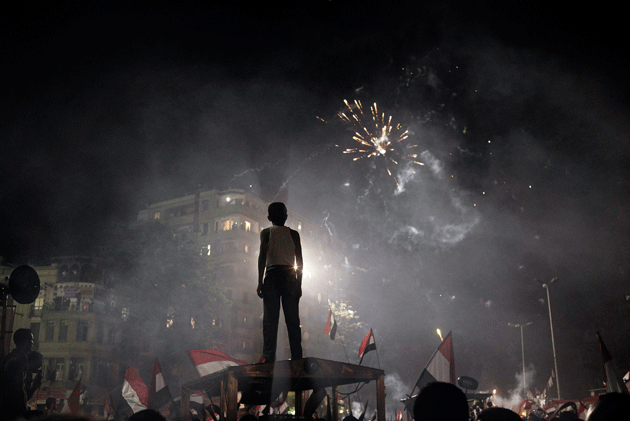

Fireworks light the sky after demonstrations turn to celebrations in and around Tahrir Square following Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi’s ouster and arrest by the military, July 3, 2013 © Yuri Kozyrev/NOOR

And then came the petition. Branded Tamarod — “rebellion” in Arabic — and drafted by a group of youthful activists, its language was fresh and secular and laid the blame for the miserable state of the country on Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood. (“I withdraw confidence from the President of the Republic. . . . I hold fast to the goals of the revolution,” it read.) Organizers said they had collected 22 million signatures, though the number was impossible to verify. When, on June 30, 2013, millions of Egyptians descended into the streets — hundreds of thousands of them back to Tahrir Square, where they had unseated Mubarak just two and a half years before — it was with Tamarod’s imprimatur.

These protests, the newscasters said, were even bigger than those of the 2011 revolution. The BBC reported that they might be the biggest in human history. The superlative, though swiftly retracted, went viral and took on the aura of truth. Some simply referred to the events as Egypt’s second revolution. A friend who went to the square that day with her mother sent me a text message that read: “We did it again.” In that moment, I didn’t know what she meant. In many ways, I still don’t.

On July 3, 2013, with Tahrir Square and other gathering spots around the country still crowded with Egyptians, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi — then commander of the armed forces — stood before state-television cameras and, in a coolly laconic manner, announced that Morsi had been deposed. With that, the first freely elected president in the country’s history was out of a job — kidnapped, actually. It was only some weeks later that we learned that, like his predecessor, he was in detention. Another president, another set of prison bars. We did it again.

For the second time in three years, the military had stepped in to steward a leaderless country. And for the second time, a majority of Egyptians feted them. Military jets drew loopy hearts of smoke in the sky above an ecstatic crowd in Tahrir. The army and the people are one hand, the decades-old saying goes.

Yet to Morsi’s supporters, most of them members of the Muslim Brotherhood, the men in uniform had undone a free and fair election. The term “coup d’état” spread among the Morsi faithful. Thousands of them gathered shoulder to shoulder in two huge sit-ins — one in al-Nahda Square, not far from Cairo University, and the other one, larger, outside Rabaa al-Adawiya mosque in the high-rise-heavy suburb of Nasr City. Both sit-ins, it turned out, would end badly.

From the beginning, there was an enormous gap between how the foreign press and the local media reported Morsi’s ouster and Sisi’s ascent. Foreign pundits, writing in such publications as the New York Times and the Guardian, spoke of “counterrevolution,” “coup,” and the return of the “strongmen” — in this case, the Egyptian army. In their view, Egypt’s brief flirtation with democracy had come to a painful end and Sisi would join the pantheon of Middle Eastern military despots, from Saddam Hussein to Muammar Qaddafi. The Egyptian media, on the other hand, welcomed the strongmen enthusiastically. After all, they had saved Egypt from a madman at the center of the Muslim Brotherhood — the same shadowy organization, some pointed out, that had historical ties to Al Qaeda.

These two views duplicated, in a way, the debate within Egypt itself, where the language used to talk about the situation remains fraught. In most non-Islamist circles, to utter the word “coup” inspires accusations of all sorts — of softie leftist naïveté about the threat the Brotherhood poses, or of being part of a global conspiracy to facilitate the organization’s rise. To partisans of this view — and they reflect the mainstream in Egypt now — what happened in the summer of 2013 was not a coup d’état but a popular revolution in which a Muslim-majority country overthrew an Islamist regime.

A protester sits amid rubble during the clearing of one of two pro-Morsi sit-ins, near the Rabaa al-Adawiya mosque, August 14, 2013 © Mosa’ab Elshamy/Getty Images

Sympathetic to this line of thinking, the Egyptian media either willfully ignored the pro-Morsi sit-ins — they lasted six weeks — or presented them as a sort of Woodstock for terrorists. At its peak, Rabaa, the larger of the two, began to look and feel like a miniature city, complete with a barber, a pharmacy, restaurants, and kiosks selling all manner of products, as well as a media center stocked with iPads and equipped with high-speed Internet. Yet it was difficult not to think of Rabaa — thanks to its association with gruff bearded men, Islam, and extremism — as the poorer, less photogenic cousin of Tahrir Square: Egyptian coverage involved gossipy depictions of Morsi supporters as bin Ladenists or witless lambs in thrall to terrorist leaders. The camp, which would swell during the demonstrations to a population of as many as 85,000, was described as teeming and unhygienic. The women, the state newspapers said, were there only to give sexual pleasure to the jihadis in their midst. There were few photographers present from the mainstream Egyptian press, and few uplifting images of bravery in the face of adversity emerged. After the sit-ins were broken up — as a result of which around 900 protesters died — Egyptians didn’t memorize the names of Rabaa’s dead, nor did they commemorate them with posters, murals, syrupy music videos, and decorative air fresheners. According to Mosa’ab Elshamy, a young photographer who exhaustively documented the sit-in, the Egyptian newspapers warped the story. “One or two newspapers might have sent photographers, but as far as I know they never printed any images of the raid.” His own work, which ended up on the front page of the New York Times, had no life in the local press.

The pictures that do exist — you can dig up material on Google and YouTube — reveal police descending on the stubborn encampment on the morning of August 14 with tear gas and bulldozers. Female members of the sit-in read aloud from the Koran, oblivious to the helicopters flying overhead and the soldiers with bullhorns calling for the camp to disperse. Children struggle to breathe in a fog of tear gas, and an endless stream of bodies and blood flows toward a makeshift hospital on the edge of the encampment. Footage inside the hospital itself reveals human forms with bullet wounds and collapsed skulls, and rows of white body bags in overcrowded rooms, arms folded over chests to form a sea of awkward humps.

As with any war of images, the pro-military camp, backed by the official media, has its own stash of videos uploaded to YouTube. For every clip of soldiers stamping out an ostensibly peaceful protest, there is another put out by the pro-military faction that features menacing-looking members of the sit-ins bearing arms. In one such video, snipers can be seen firing at troops from a nearby building. Another, since removed, showed a coffin the police claimed to have found filled with ammunition. “The history of what happened at Rabaa,” Elshamy said of the media blitz, “is being rewritten.”

At Rabaa, the first coats of white paint came at the end of August, less than two weeks after the last of the bodies were cleared out. Next came the shrubbery — potted trees and the kind of floral gestures one associates with gated communities and mental asylums. Later, the abused roads surrounding the mosque were repaved, except this time, rather than using individual stones — which could be pulled up and hurled during street fights — officials opted for smooth concrete. The monumental marble sculpture at the heart of the square came soon after, something that the Russian constructivists might have dreamed up. In the pages of a number of Egyptian dailies, a man identified as the chair of the Cairo General Authority for Cleanliness and Beautification explained that the sculpture — a pair of boxy stone hands cupping an orb — represented the army and the police protecting the Egyptian people. Beyond a shoddily patched bullet hole here or there, there was no sign that this square was the site of the deadliest massacre in modern Egyptian history. Soon it would be back to normal, the Cleanliness and Beautification chair confidently continued, commenting on a dramatic refurbishment that cost close to $12 million and involved the removal of thirty tons of unidentified “waste.”

For those in the fervent anti-Morsi bloc — and there are many — Egypt is still in the midst of a grisly war on terror. The mass deaths of Morsi supporters at last summer’s sit-ins were, by this logic, justifiable: You can’t negotiate with the Brotherhood. In an art gallery in the upscale neighborhood of Zamalek one day, I stood next to two women gazing at a canvas that featured the word love fashioned from pieces of broken glass. “Even if you say three hundred or three thousand died, I don’t care. It should have been thirty thousand,” one said to the other. What struck me was not what she said but how unsurprised I was to hear it. In Egypt today, hers is not an uncommon sentiment.

Three hundred or 3,000: the numbers are wildly divergent. We know some things for certain. On June 30, the bridges and squares of the country were filled with so many people calling for Morsi to step down that an aerial view amounted to a pointillist portrait. But was it 14 million? Or the frequently cited 34 million? We know that many were killed when police and military forces raided the two pro-Morsi sit-ins. But did 638 die? Two thousand? Two thousand six hundred? The promiscuity of the facts seems to say a great deal about the times. Revolution or coup? War on terror or massacre? Military or Brotherhood? Whose side are you on? Each set of numbers has its passionate partisans. At its best, each version of events is utterly convincing.

For the past year, Egypt’s official and semi-official media have consistently communicated a single narrative: The day Morsi was deposed was the day Egypt was saved from certain doom. Every night, television hosts bellow, moralize, and jab with their narrowly nationalist mantras. Many of the best-known television personalities hail from what is referred to, playfully, as the School of Okasha, named after Tawfik Okasha, a man of small stature and significant bile who once served in parliament as a member of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party. In his weekly show on Al-Faraeen, the satellite channel he owns, he relays juicy details about the Muslim Brotherhood’s elaborate plot to take over Egypt. He is often described as Egypt’s Glenn Beck. A running list of headlines from Al-Faraeen, as well as a handful of other news outlets, from the past year:

how the brotherhood-hamas network resembles a satanic terrorist cult

former salafi woman recounts journey toward atheism

since the beautiful second revolution of june 30, more and more women are casting off their veils

leading psychiatrists confirm that morsi had a history of mental problems

pop star sings a song entitled “the army is in our hearts”

dog barks to tune of national anthem

For those who stray from the establishment line, there are grave consequences. In June, the popular comedian Bassem Youssef — the Western media had taken to calling him Egypt’s Jon Stewart — was forced to take his show off the air after he made jokes about the uniformed men running the country. Most Brotherhood-associated channels have been shut down. Journalists have been imprisoned for alleged Brotherhood sympathies, denounced as agents of the terrorists and their foreign backers. Lazy comparisons of Egyptian establishment television to Fox News are not entirely unfounded: in the summer and into the fall, a number of channels sported a small icon in one corner of the screen that read war on terror, egypt’s war on terror, or some variation thereon.

In November, I visited the newspaper editor and television host Ibrahim Eissa, one of the most distinguished — and unlikely — members of this war chorus. In 2006, Eissa, a round man with round eyeglasses and a full, fleshy face, was accused of multiple offenses, including insulting Mubarak, speculating about the president’s poor health (a prosecutable crime), and generally being an advocate of a free press under a regime that would entertain no such thing. Eissa never actually spent time in prison, but he won many awards for his bravery. Back then, I would occasionally see him at his offices at Al-Dustour, an independent opposition newspaper, and listen to his long, elliptical discourses about the tyrannies of the state, peppered with an occasional “Fuck heem!” (“heem” was Mubarak). Three years and one president later, I found him energized by the June 30 uprising against Morsi — what amounted to, in his words, “a rejection of the terrorist Brothers.” Perched on the edge of a very small desk at the headquarters of his new newspaper, Tahrir, he looked a little like Humpty Dumpty, magically defying gravity thanks to his suspenders. “The foreign media says that Egypt is polarized. This is wrong. . . . The foreign media backs the Brotherhood. The Brotherhood gives them statements and money.” He looked me in the eyes as if I, too, might be the beneficiary of Brotherhood kickbacks. “If you call June 30 a coup, you insult the Egyptian people. When the military responds to twenty-three million people on the streets, do we oppose them?”

Back in December 2011, Eissa had authored a front-page article about the very military he was now in the thrall of: the word liars (“kazaboon”) was splayed across the top in huge letters. Above the headline was an image that, along with the pictures of marauding men on camels and the three Mubaraks in a cage, has come to define Egypt in the post-Mubarak era: a female protester being kicked and dragged through the street by thuggish, helmet-clad military police, her shirt pulled up to her neck so that her aqua-blue bra was exposed for the world to see. My eyes settled on the well-polished trophies behind Eissa’s head. It was difficult not to wonder how such a dramatic volteface was possible.

“I’ve never felt so alone,” Hossam Bahgat told me one day last fall in the office of the organization he founded a decade ago, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights. The room we sat in was unadorned in the way that offices of extremely busy people often are. Bahgat, who is a boyish thirty-four and widely respected in human rights circles, had just finished reviewing a statement to be issued from thirteen local and international human rights groups calling for an investigation into the killings at Rabaa and al-Nahda. “It’s been a battle to get this off the ground,” he explained. “We don’t all see eye to eye on this.”

For members of Egypt’s small, embattled human rights community, one of the most painful aspects of the past year has been losing colleagues and friends — many of whom had spent years agitating against military abuses — to the pro-military camp. Following the violent dispersal of the sit-in at Rabaa, some of the country’s oldest human rights groups, such as the Egyptian Organization for Human Rights, awkwardly stood on the sidelines. Some even maintained that the use of force had met “international standards.”

Over the removal of Morsi too, the community is divided. While Bahgat and others argue that his ouster has delegitimized Egyptian democracy, a few go further, suggesting that Tamarod, the much-romanticized campaign to unseat Morsi, was very possibly backed by elements of the security establishment, the military, and the old regime. (A number of journalists, such as Dilip Hiro in The Nation, have written about significant army and police infiltration into Tamarod.)

Those, like Bahgat, who have rejected the crude binary of Brotherhood or military have swiftly become the objects of vitriol, accused of dragging the country into chaos without end. “We’re turning into Syria because of people like you” was a common — though wholly inaccurate — refrain. “July and August were the hardest,” he told me. “I couldn’t post a link to Facebook without someone accusing me of being a Brotherhood sympathizer. We’d entered the golden age of fifth columnists.”

As with any war on terror, this one has had distorting effects. Just as happened in the United States shortly after 9/11, Egypt has lost many of its best liberals to a devil’s pact with the uniformed men in power. Among them was the novelist Sonallah Ibrahim, a man some readers lovingly refer to as the Egyptian Kafka for his spare accounts of life in a sulky, morally bankrupt, overcommercialized society in which the only outlet is joyless masturbation. For many of these liberals, the military represents a lesser of two evils, a vote for a familiar Nasserist brand of secular nationalism over an unfamiliar theocracy. And anyway, they might add, Egypt under Morsi had been falling apart. It might have become a failed state. It might have gone the way of Iran, dragged back into the Dark Ages by an Islamic revolution. In an interview with the independent newspaper Mada Masr on October 26, Ibrahim said of the raid at Rabaa, which he supported: “it wasn’t a massacre.” He was one of 150 prominent writers and publishers to sign a statement in August demanding that the Muslim Brotherhood be declared a terrorist organization. “Those who incite violence and murder deserve prosecution for their crimes,” it read. The fact that the statement was released just before the raids at Rabaa makes it difficult not to interpret it as, in the words of the American scholar Elliott Colla, “a permission slip to commit atrocities.”

Today, the revolutionaries once feted on the cover of Time and subject to rapturous odes at home and abroad find themselves both divided and marginalized. The Google Guy, the Frizzy-Haired Activist, the Tweep: each had become a familiar figure in a popular drama that pitted the secular, computer-savvy youth against the out-of-touch dictator. Now these figures of the revolution — themselves breathtakingly successful media creations — are personae non gratae. They never managed to present a substantive alternative to the Islamists on the one hand or the army on the other, and as a result “those kids in Tahrir Square,” as Secretary of State John Kerry once referred to them, are linked in Egyptians’ minds with never-ending protests, rising crime, even the stinky clumps of garbage in Cairo’s streets.

A November 13 article in El Youm El Sabaa, a newspaper of statist orientation, evoked the stereotype of the average activist in Egypt today. The article’s style approximates that of an FBI most-wanted poster:

The male activist is unemployed, soft, and effeminate, with long hair that is either braided or disheveled, and he wears a bracelet and a Palestinian keffiyeh. He has a Twitter account, a Facebook page, likes to curse and use disgusting obscenities. . . .

On the other hand, the female activist takes on the male role — she “mans up.” She listens to the songs of Sheikh Imam and the lewd poetry of Fouad Haggag and Naguib Sorour. She “likes” all the pages that use foul language and puts pictures of the great revolutionary Che Guevara on her Facebook and Twitter profiles.

It continues:

These activists are more dangerous to Egypt than the terrorist Muslim Brotherhood, whom they resemble in their partisanship and extremist ideas.

In December 2013, the military-backed government arrested four of the most prominent organizers of the anti-Mubarak uprising: Ahmed Maher, Mohamed Adel, Ahmed Douma, and Alaa Abd El Fattah. I saw Abd El Fattah, an old friend who, with his wife, Manal, virtually established the Egyptian blogosphere, in late October. We met at the Gezira Sporting Club, a former British officers’ club nationalized in the 1950s, where he was entertaining his young son, Khaled, named after one of the most famous victims of police abuse in Egypt, Khaled Saeed. Abd El Fattah, who comes from a family of distinguished activists, had been in and out of prison so many times since we met, in 2004, that #FreeAlaa had permanently become my Skype moniker. As we prepared to leave, he joked that some of the club’s well-heeled members, many of whom are rabidly pro-military, might have a go at him. “I’ve gone from the revolution’s hero to deeply unpopular in record time,” he said, laughing. When I learned, a few weeks later, that he’d been arrested again, it seemed to confirm the return to the security-state mentality of the Mubarak era.

Al-Ahram, November 3, 2013: french intellectual says that sisi is the most popular man in egypt.

The man of the hour is Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. He makes women swoon. His voice is as sweet as honey. On a day now memorialized as “the Friday of authorization,” he was licensed by the Egyptian people to break a depressing cycle of protests and economic chaos. Emboldened by the gravity of his errand, he will restore Egypt to its historic greatness in the eyes of the world. The Egyptian army, he says, is like a pyramid: “It cannot be broken.”

In December, Sisi beat out both the Turkish prime minister and Miley Cyrus in a poll for distinction as Time’s Person of the Year (“climbing to power on a bed of corpses,” as one Twitter user memorably put it). This, of course, is the same Sisi who served as head of military intelligence under Hosni Mubarak. The same Sisi who defended the army’s use of virginity tests for female protesters in 2011. The same Sisi who, as the top security official for internal affairs, presided over the raids on the sit-ins at Rabaa and al-Nahda.

To understand the cultish enthusiasm for Sisi, I visited Zahi Hawass, the controversy-prone Mubarak-era minister of antiquities, in his office in the Cairo neighborhood of Mohandisin. The space, filled with books written by Hawass and at least a dozen honorary degrees, was in the sort of 1960s high-rise that, before it fell into grimy disrepair, probably communicated urgent urban modernity. Hawass, a vigorous, silver-haired sixty-seven-year-old, has seen his fortunes steadily decline since the fall of Mubarak. In the first days of the 2011 uprising, he passionately declared to the BBC, “The president would like to stay and all of us would like him to stay.” When that president fell just five days later, Hawass scrambled to distance himself from those words. Still toeing the party line, he related a story drawn from history to demonstrate why Egypt desperately needed Sisi: “He is like Mentuhotep II. Forty-two hundred years ago, a man named Pepi II ruled Egypt. But there was so much corruption in this kingdom. A revolution began and it went on for a hundred and fifty years! Finally a strong military man from Upper Egypt came and put people to work. His name was Mentuhotep II, and today that man is Sisi.”

More animated now, he continued, “Egyptians love two things: heroes and national projects. Like the pyramids or the High Dam at Aswan. Sisi represents both.”

During the next two weeks, I collected the names of at least a dozen people who claimed to be the official spokesman for Sisi’s presidential campaign. Sisi’s candidacy had not been announced; he had denied that he would even run, and no one seemed to know when elections would take place. He did, however, boast all the requisite commemorative accoutrements of a candidate — T-shirts, mugs, fruit tarts, and chocolates with his face artfully rendered on their surfaces; Sisi sandwiches; Sisi cooking oil; pop songs written in his honor; a line of lingerie with his face square on the pubis. The celebrity knickknackery only lent more drama to his ardent denials that he might serve as Egypt’s new pharaoh. So, too, did leaked audio in which he recounted his dreams to a sympathetic journalist. In one dream, Sisi explained, he was told by the late president Anwar Sadat that he, too, would become president.

One of the handful of Sisi campaign spokespeople I met — a businessman by the name of Mohamed Shaheen who had the distinctive blandness of a yes-man out of a Naipaul story — presented me with a bullet-point manifesto as to why Sisi should lead the country. As with the other self-proclaimed campaign spokesmen I met, we convened in an overdecorated but as yet unused office. “The Morsi experience tells us someone from outside will not work,” he told me. “We have to cleanse the rottenness. We need someone who knows the system.” In the absence of any discernible vision or program, Sisi and his courtiers were counting on his pop-star popularity to land him the presidency.

“After Gamal Abdel Nasser, no one has been as popular as Sisi,” Shaheen said. “No one can beat him.” And then that word again: “He will make everything clean.”

Cleaning is at the heart of one of the narratives I’ve heard time and again from military supporters. It goes something like this: Liberals in the West supported the Islamists because they wanted them to learn how to be moderate. By taking part in elections, they would avoid becoming suicide bombers who would in turn attack America. It is circuitous, but makes sense in the way some parents believe smoking pot with their kids might one day prevent them from graduating to cocaine or heroin. Egyptians of the anti-Islamist bent say that they, too, want to purge their country of these terrorists — the West thinks that keeping them in Egypt will keep them out of the United States, but Egyptians retort that they don’t want to live with them, either. Not only do they not want to live with them, but many — disappointed by the sputtering economy and unmoved by the plight of the Islamists — are willing to live with the restrictions of a country “at war.” A law passed last year, for example, prohibits public gatherings of ten or more people without a special permit. More recently, a decree criminalized both failing to stand for the national anthem and disrespecting the flag, and the interior ministry has begun exploring a plan to monitor social media that would, in the words of the ministry, discourage the spread of “destructive ideas.”

Early this year, Egyptians voted on a new constitution in a nationwide referendum. In the days leading up to the vote, the interim administration launched an aggressive media campaign urging citizens to vote yes. To fail to do so was not only unpatriotic, the various advertisements, jingles, and public-service announcements suggested, but also an endorsement of the terrorist Brothers. Seven people distributing “no” posters around Cairo were arrested, and at least eleven people, most of them from the “no” camp, were killed in scuffles around the country. One news program interviewed a woman who had proudly turned her son in to the police because he planned to vote no.

When the new constitution passed with 98.1 percent of the vote — numbers reminiscent of Mubarak’s time — it was widely viewed as a mandate for the military-backed government and for General Sisi, its chief ideologue. The document itself is not terribly unlike its predecessor from the Morsi era, though it does go further in safeguarding minority rights and also — in a clear rebuke to the Brotherhood — bans any political parties organized around religion. As far as offering civilians protection from military courts, a central demand of the human rights movement, the new constitution fails. It fails too in protecting journalists — whom it states may be arrested if their work threatens either national security or the economy. The text also strengthens the armed forces, an institution of already considerable means, providing for a military budget that is immune from parliamentary oversight. As the Cairo-based British-Egyptian blogger Sarah Carr put it, the new constitution’s passage represented “another brick in the wall of the security state.” Yet an article on the merits of the constitution by a writer named Lubna Abdel Aziz in Al-Ahram captured the syrupy mainstream-media sentiment:

Out of nowhere appeared a man of the people, brimming with humility, compassion, and courage, with a voice as soothing and caressing as the gentle rains from heaven, alleviating every pain, healing every wound, wiping every tear. Backed by the army, General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi stood behind the citizens. The tyrant Morsi was removed from office, incarcerated with his cronies.

Today, Morsi remains in prison. His excessive shouting during his first appearance in court eventually inspired the innovation of a soundproof cage (he’d bellowed to the presiding judge, “Do you know who I am? I am the president of the republic!”). If convicted on charges of incitement to murder, he could face the death penalty. The Muslim Brotherhood, for its part, was officially declared an illegal terrorist organization on December 25 of last year, after the bombing of a security building in the Nile Delta city of Mansoura. Though an Al Qaeda affiliate from Sinai took responsibility for the bombing, it was, to the military, a welcome opportunity to underscore that terrorists were in Egyptians’ midst. It seems that no one is beyond suspicion. Early this year, government officials went so far as to accuse a puppet wearing hair rollers of serving as a terrorist mouthpiece. Named Abla Fahita, she appears in a Vodafone ad on TV and babbles incomprehensibly into the phone. The puppet’s detractors have claimed that the babble constitutes a secret message to the Muslim Brotherhood.

More than 16,000 Islamists, including members of the Brotherhood and their alleged supporters, are still behind bars; hundreds picked up in the aftermath of the Rabaa raid remain in prison with no indication as to when they will be released. In April, 680 supporters of the Brotherhood, including the group’s spiritual leader Mohamed Badie, were sentenced to death in connection with the killing of one policeman in the governorate of Minya. A fact-finding investigation launched last December into the deaths of protesters at Rabaa and al-Nahda has been slow to get off the ground, delayed until October at least. One month after I last saw Hossam Bahgat, he stepped down from his position as director of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights. Alaa Abd El Fattah was released on bail in late March, following four months of imprisonment. On June 11, after being denied entry to the courtroom, he and twenty-four other defendants were sentenced in absentia to fifteen years in prison on charges of organizing an illegal protest and attacking a police officer. In an interview with Democracy Now! after his release on bail, Abd El Fattah spoke of a “war on a whole generation.”

Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, to no one’s surprise, was elected Egypt’s president on May 29, 2014, with 96 percent of the vote. (After two days of lackluster voting in which polling stations around the country were deserted, election officials announced an unprecedented third day of voting. At least one official said that voters were free to draw hearts on their ballots if they wanted, and talk show hosts — Tawfik Okasha and Ibrahim Eissa among them — begged Egyptians to put their faith in Sisi.) Sisi barely campaigned — though he made good on a promise to distribute thousands of energy-saving lightbulbs — and gave only a handful of interviews, all of them elaborately stage-managed, in which he addressed the Egyptian people as if they were a band of unruly Boy Scouts (“Will you bear it if I make you walk on your own feet? When I wake you up at five in the morning every day? Will you bear cutting back on food, cutting back on air conditioners?”). Sisi’s only opponent, a mild-mannered Nasserist named Hamdeen Sabahi, garnered less than 4 percent of the vote.

One crisp early morning last year, two days before the two-year anniversary of clashes that had ended in nearly fifty deaths at the hands of the interim military government, the beginnings of an odd monument began to take shape in the center of Tahrir Square. The structure, which for most of its short life resembled a blown-over sand castle, slowly began to approximate a ramp leading up to a podium that might, in turn, accommodate some future sculpture. One resourceful journalist tracked down an engineer who’d worked on the design, who told her that he had been called by a government official: “He said to me, ‘Go to Tahrir now. We have an assignment for you.’ He told me, ‘You have to start building tonight.’ ” The engineer added, “I have not slept.”

This memorial, the state media revealed, was meant to honor those who had lost their lives in that fateful battle two years ago. The morning before the anniversary, a red carpet was rolled out and a tent was erected to host a commemoration by the interim prime minister, Hazem al-Beblawi (who would on that same day refer to members of the Brotherhood as mosquitoes that bite you when you sleep). Rental flowers were trucked in and large Egyptian flags were planted. A red-uniformed band played ceremonial music in the background. The prime minister, the man whom most Egyptians would be hard-pressed to identify in a lineup, addressed the deceased: “Your sacrifices will not be forgotten.”

By afternoon, protesters — a mix of young secular revolutionaries, some street children, and a handful of Islamists — were milling around, many of them wearing eye patches in solidarity with those who had lost their eyes in the clashes of two years ago, when police purposefully aimed rubber pellets at protesters’ eyes. Some toted oversize black-and-white banners bearing the faces of the martyrs. They chanted against a government that had erected a monument dedicated to the memory of those it had killed.

In the early evening, solemnity gave way to anger as protesters began hacking away at the yellow bricks. A ceremonial plate with the names of the dignitaries present at that morning’s inauguration was smashed. By midnight, the whole of the memorial had been reduced to a leprous stump, its surfaces ringed with red graffiti. In place of the sculpture that would never come, a black coffin was hoisted. Someone pointed out that it was in fact General Sisi’s birthday, and so a happy birthday general was added to the growing body of graffiti against the Brotherhood and the military (including some choice words about the General’s mother’s private parts). In this way, the battle for meaning and memory continued, and the square — if only for one evening — was reclaimed by the long-haired Che-worshipping revolutionaries who had occupied it in the first place.