“The thing you have to understand is that I really don’t understand people.”

Gil sat on a squashy old sofa, legs akimbo, forearms on thighs. He was wearing a dark-green polo shirt with a small red turtle in the place where a more fashionable polo shirt sports a crocodile. It had the trusting incomprehension of a presidential dog.

“I mean for instance. Peter Dijkstra. There are these people, they totally say Dude, Peter Dijkstra, I love Peter Dijkstra, what a genius, but then they say Oh, but he’s impossible, we met him for drinks in Amsterdam and he spent the whole night talking to the bartender’s dog! And then he walked off with Jason’s brand-new Moleskine!”

It is not new information that he wore a dark-green polo shirt with a turtle on the left breast, but sometimes we can’t be rational. If a garment quietly clothes its owner while he speaks, this cannot be uncomplaining loyalty, it cannot be touching, because this is what garments do. (What else would it do? Walk off in a huff?) And yet there was a touching loyalty in the quiet uncomplaining persistence of the turtle on the dark-green breast. It had been there and it was still there.

“But see, this is what I don’t understand. Because see. Say Peter Dijkstra comes to New York and needs a place to stay, he can come to my place and stay as long as he wants and I’ll just go off and couch surf with friends to get out of his way.”

The friendly crowd let him talk uninterruptedly on. They filled the loft that would be placed so gladhandedly at the disposal of Peter Dijkstra.

“Okay, now let’s say I’m off the premises and Peter Dijkstra rents a van and loads it up with everything I own. I go back and everything is gone. Books, CDs, DVDs, TV, computer, baseball cards. Gone. And it’s not just the stuff, Peter Dijkstra went through my papers, my personal papers, and he took my diaries, and my notebooks, and my photo albums, all this incredibly personal, irreplaceable paraphernalia, he just took it. The place is empty. All I’ve got is the clothes I’m standing in, my laptop, and my iPhone. So I’m standing in this empty apartment, and I’m looking around, and the point is, I’m happy. I’m ecstatic. Peter Dijkstra — Peter Dijkstra! — has appropriated this stuff, in some mysterious way my stuff is going to contribute to a book by Peter Dijkstra! I feel honored. I mean, the stuff is not contributing to a work of genius just sitting there in my apartment.”

What could anyone do but smile and feel shamefaced, crass? It was as if he was the only one in the room unconscious of the reviews, the prizes, the sales. With a little luck someone might compete for the reviews, the prizes, the sales, but who could compete for the absence of consciousness?

(The unpretentiousness of the humble turtle — it’s hard to explain how this contributed to making people feel shamefaced and crass, but it did.)

“So the thing of it is, is that Peter Dijkstra does not have it in his power to betray me, if he thinks something of mine can help with his new book he can just have it. Not only is he not letting me down, this has been a fantasy ever since I was a kid. I don’t care about the things, it just makes me happy to be part of this. So when I say a writer is a genius, what I mean is, there is nothing I won’t do for him. It’s really simple. Same thing with friends. When I use the word friend what I mean is, ‘What’s mine is yours.’ It’s really really really really simple.”

People were laughing, smiling, drinking their beers. It was kind of upbeat to hear except that presumably, then, no one in the room was even a friend?

Rachel sat cross-legged at the other end of the squashy sofa. Silky black hair drifted over her shoulders; glass-green eyes, a bittersweet mouth endorsed uncalculating simplicity with their beauty. She wore a black T-shirt with white stick figures who said:

MAKE ME A SANDWICH

WHAT? MAKE IT YOURSELF.

SUDO MAKE ME A SANDWICH.

OKAY.

This T-shirt too had the lovable cuteness of the First Dog.

Cissy stood at the back of the crowd in the cruel grip of consciousness.

Cissy had met Peter Dijkstra in Vienna. She had booked a room through venere.de but it had fallen through: an apologetic email in exquisitely courteous German had explained that the room had been booked through another booking service a few minutes earlier. She had been offered an alternative but instead had found Angel’s Place through booking.com, closer to the center and with the look, somehow, of a hi-tech monastery. The rooms were underground, with very white plaster walls, arched ceilings of bare brick, and fierce gleaming black flatscreen TVs. It was enchanting. And then there were only four rooms, so unlike the free-for-all of a hostel, it would be silent, pure, a place to read and think and write. And so she had taken the train down from Prague and checked in late and gone out in the morning for Sachertorte at Oberlaa Kurkonditorei and wandered all day.

She got back very late, close to midnight. In the breakfast room at street level a man sat reading. He held a pen; a notebook was open. It was as if she had walked into a hotel and found Wittgenstein writing quietly at a table.

He looked older, wearier than in the only picture anyone had seen, though his very pale hair would not show gray. He was unassumingly dressed in the way that older Europeans are unassuming: he wore a short-sleeved blue-and-white checked shirt, well, white with pale-blue double lines in a grid, and faded gray pants, and stout brown walking shoes. He did not bother to look up when she came in.

She could not bring herself to speak. She could not bring herself to go to her room. She went to the kitchen for a glass of water. She heard the scrape of his chair. When she turned she saw him standing, holding a pack of Marlboros. He went to the door and into the street.

The book, she saw, was Detlev Claussen’s biography of Adorno; he had left it open face-down on the table. She would have liked to look at the writing on the page of the open notebook but she knew it would be bad. She put water into the coffee machine and slotted in a capsule of espresso.

The door opened just as the coffee began to drip into the little plain cup. She knew she would hate herself always if she did not speak. She said, “You’re Peter Dijkstra, aren’t you? I love your work.”

He said, “Thank you.”

She said, “Do you like Vienna?”

He said, “Very much. It’s my first time, for one reason and another.” (She knew that he had been in an asylum for five years.)

He said, “They speak German like robots. It’s pleasant hearing a language mechanically spoken. I wish I had known.”

He said, “Adorno came as a young man to study with Alban Berg. Claussen is quite amusing on the subject.”

But he had picked up the book and put his pen in the fold to mark his place and closed it and he was picking up his notebook.

“Don’t let me disturb you,” she said. “I was just going to bed.”

“So am I,” he said. “That was my last cigarette for the day.”

In the morning she asked Angel if she could extend her booking for a week.

She would have liked to tell this story, she desperately wanted to tell this story and be drawn to the squashy sofa to be pumped for details, singled out for envious excited questions and exclamations and comments, enfolded in the collective embrace. But she had not been invited. Nathan had told her to come because Gil was a friendly guy, but he had not been able to introduce her while Gil was talking and now he was talking to other friends.

She stood awkwardly at the back.

Across the room she saw Ralph, who had found a publisher for her book when no one was buying. He caught her eye and smiled and she drifted across. He wore a pale-aqua polo shirt with a crocodile on the breast, chinos, and sockless Topsiders, because he had never wanted to be a suit.

He had not done for her what he had done for Rachel, who floated now on a magic carpet.

“You should represent Peter Dijkstra!” she said gaily. “I met him in Vienna. I could put you in touch!” It felt like a thing to be doing. She imagined Peter Dijkstra in New York. There would be an inner circle of admirers. Some kind of dinner, maybe, conferring over what could be done for the genius. Sontag had introduced Sebald to New Directions.

Peter Dijkstra in New York, the inner circle, Sontag, Sebald, New Directions — she was not the only dreamer in the room.

Peter Dijkstra lay on a very white bed, his head on his arm. The television was on; German tripped off the metal tongue of a female chat-show host.

At 2:00 a.m. he went upstairs with his laptop and cigarettes.

An email from his editor at Meulenhoff forwarded five emails from altruists across the pond, relaying the declared devotion of a young American writer of some fame.

He went outside to smoke a cigarette.

He did not want to be locked up again. He was sane enough as long as he lay on the bed watching TV, or stood in the street smoking a cigarette, but it’s true, the bills did mount up. He was sheltering under his credit cards.

Somehow, though. The fact that a fame-kissed young American would happily hand over all his worldly goods did not make it socially straightforward to write asking for a gift of 20,000 euros. If something was not socially straightforward he could feel his mind cracking. He wondered whether the boy might in fact give him a place to stay if he went to New York, but it seemed terribly complicated. If the boy did move out it would be all right, but if he did not it would be impossible. He could not think of any sentences that would ascertain the position in a socially acceptable fashion.

Anyway, it was comfortable among the robots. Americans are so natural and friendly and sincere. The Viennese have the mechanical, predictable charm of a music box; you don’t have to warm to it. He would have liked it if the boy had set up an account for him at a pastry shop. That would have been a nice gesture. The Wiener Phil — imagine if an admiring reader were to give him a subscription! Americans do like you to warm to them, and he thought he might very well warm to someone who gave him a subscription to the Wiener Phil, but it did not seem a very American thing to do. An American, he thought, would see it as too finely tuned.

A Hungarian might do something lavish and extravagant along those lines. He might keep madness further at bay if he took to writing in Hungarian.

Come to think of it, a limitless supply of Marlboros would not come amiss — but no, an American would find that quite shocking.

Cissy knew she had to be in New York, and she knew Ralph had to do the things he was doing for her, but oh! it was horrible, grubby and horrible. People he knew had read her book and sent quotable quotes and now her book would be plastered with names of people whose work she despised. Was it like this in Europe? She wished she was back in the white cellar with its green-and-white tiled bathroom and its gleaming black flatscreen TV. It would be so different, so different and good, if her book were read by a man in an unassuming checked shirt who smoked Marlboros and called Adorno Teddie Wiesengrund the Wunderkind. It wasn’t about the quotes, though if the name could go in the book with all the others plastered there she would not feel so sick.

She ran into Rachel at a party at KGB Bar. She said, “I think we should do something for Peter Dijkstra!” (She did not know whether Ralph had asked Rachel, and this way she did not have to think about it.) She talked wildly and impulsively and enthusiastically.

Rachel said, “Well, I love Peter Dijkstra.” She wore skinny white jeans and a sloppy lilac-blue V-neck sweater, sleeves rucked up to her elbows, cashmere. She was drinking Campari. She said, “But I don’t know. He seems pretty private, or at least that’s the way I imagine. Let’s see what Gil has to say.”

Gil had come back from the bar. He said, “I’m a sucker for really good vodka. They have stuff here you just don’t see anywhere else. I’m behind on a deadline, but hey, maybe there’s a reason for that. Maybe the piece needed an authentic Russian vodka with an authentically unpronounceable name.”

Cissy told the story of walking into Angel’s Place. She said it was like walking into a hotel and seeing Wittgenstein writing at a table.

“Awesome!” said Gil. He did not pump her for details, but she gave some anyway.

She said, “I think we should do something!”

“What kind of thing?” said Gil.

She did not really know. She did not know enough to know the kind of thing. She babbled about conferences, readings, a lecture. She said he should have a trade publisher, like Sebald, a book deal with a lot of money.

Gil took a swallow of vodka. “Ahhhh,” he said.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I mean. The thing is, there are people who like that kind of thing. They like hustling, and they’re good at it. But even so they don’t just run out in the street and randomly hustle; they get approval, an arrangement, authorization. Those might be good things for him, but I wouldn’t feel comfortable rushing around and orchestrating on his behalf. And the other thing is, I’d be afraid of losing something that really means a lot to me, something very precious. Something I need so much I can’t imagine life without it. What if it changed the books for me? What if I no longer had them for myself in this private place where it’s just me and the book? It doesn’t work that way for people who like hustling, you don’t get the impression that agents have lost something they loved. But maybe that’s why it makes sense for that kind of person to do that kind of work. Does he have an agent? Maybe he should talk to Ralph.”

“I did talk to Ralph about it, but he made regretful noises about the market for translations.”

“Oh, Ralph says these things but he’s just trying to be sensible because he’s so impulsive.” Rachel, indulgent. “If he falls in love with a book he’ll besiege people.”

Ralph was not an intellectual but maybe the secret of success was not caring. Or maybe an actual genius would be so far above, would be used to being so far above, that it wouldn’t matter.

Maybe it would matter, though, that Ralph was so careful to be cautious. If you went to a café he would order wheatgrass juice and gluten-free toast with tapenade — that is, he would insist on going to the kind of café where you could order these things. Maybe a man who had spent five years in an asylum needed someone who stayed sane without effort.

Cissy knew it was not safe to say these things to Rachel. The magic carpet had carried her on but Ralph was still a good friend.

Needless to say, crowdsourcing a limitless supply of Marlboros was not an idea whose time had come.

Partly to keep madness at bay, and partly to take the most direct route to keeping his credit cards afloat, he was writing in English. He could not see the point of writing in Dutch in the hope that he would join the elect. Why should he get the lucky ticket and be translated and touted? He had had two novellas and some stories turned into English by the kind of publisher that will publish novellas and stories, and though the phrase “cult classic” had come to his ears it did not buy many Marlboros. This is what you get if you are dependent on an editor whose wife happens to know some Dutch. But if you write in English you can send the thing anywhere, you can send it to the big boys, people who wouldn’t touch a novella with a barge pole.

He had a little pack of file cards on which he wrote words and phrases that took his fancy, and he constructed stories out of them. Stories, okay, not the fast track to debt-free nirvana, but you can’t be always breathing down your own neck. Think of Gurre-Lieder. Something that starts out small and self-contained can morph (“morph”! English is so great!) into an extravaganza. You have to give the horse its bit.

He was sane enough to spot likely words in a text, and sane enough to write them on a file card, and sane enough to string them together, or rather doing these things kept his mind quiet and good. He didn’t know if he could do much more. But it was nice not having to be cheery and down-to-earth and sensible for cheery sensible down-to-earth Dutch nurses and orderlies. It was okay now to lie quietly on the bed staring at the wall.

He got an effusive email from the girl who had made coffee late one night.

Probably she got his address from the people who published the novellas.

He wrote a polite reply.

An effusive reply came within ten minutes. There was a lot more sincerity than he knew what to do with.

She mentioned talking to her agent and his regretful comments on translation in the United States.

He was already a bit tired but clearly this was a lead that must be followed. He explained a little about the file cards and writing in English.

Fifteen minutes later, when he was starting to hope that was an end of it, a new message popped up. She had talked to her agent who would love to see some pages.

He could not say why, but he really disliked that use of the word “pages.”

At this point he was ready to go back to bed.

This was not the way to deal with all those credit cards.

She had included the agent’s email address. He clicked on it and attached a Word document (after all these years he still hated Word). He explained to the agent that he normally wrote in longhand but this was what he had happened to type up.

He went outside and lit a Marlboro. If he ever had a lot of money, really a lot of money, he would just buy this place and then he could smoke inside.

Ralph called Cissy because he was simply besotted with the pages, he had devoured them at a single gulp, if the rest was anything like this —

He wrote an email to Peter Dijkstra asking for a phone number and a time when they could talk.

Peter Dijkstra was not wildly keen on the phone but these things must be done. He gave the number of the hotel and proposed a discussion at 11:00 a.m. New York time, 5:00 p.m. Vienna.

They talked for an hour because Ralph liked to really get to know people before he got to work. “I need to know what you care about,” he said. “All the best writers are obsessives.”

Peter Dijkstra said, “Well, maybe.” If you’ve been insane you mainly try not to let things get to you, but this was not necessarily a good thing to say to an agent. He said, “Actually, you know, there’s one thing. I really like the fact that ‘front seat’ is a spondee. And it’s reflected in the spelling, the two separate words. And one thing I really hate is the way they try to make you agree to ‘backseat,’ which is obviously trochaic. I don’t agree. I don’t pronounce it as a trochee, I pronounce it as a spondee, and I always spell it as a spondee, ‘back seat,’ which has the additional virtue of being logical. But then there were these ridiculous arguments.”

“Uh huh, well, I don’t remember that coming up in the pages you sent me, but if it’s an issue we can definitely deal with it. Send me everything you have,” said Ralph. He wanted to get cracking.

You’d think it wouldn’t be that big a deal, but actually typing a text always felt like this thing you see a lot in Britain, especially in terraced houses, this practice of replacing a small front garden with a slab of concrete. It was apparently quite a common part of “doing up” a house. You would ride a bus down a long terrace of lower-middle-class houses, and the ones that were freshly painted and plastered all had a square of cement where the garden had been.

At the same time, oddly enough, once the thing was typed it was up for grabs. If you wrote something in a notebook the words just were the marks your pen or pencil left on the paper, but once they were typed into Word people could smuggle in the unspeakable trochaic “backseat” behind your back.

Of course, if you want those words in a notebook to be a solution to credit-card debt, there is a bridge that has to be crossed. But if you don’t want to crack up you have to be pretty careful. But again this is probably not a good thing to say.

What he did was he seized on a phrase.

Somewhere online he had come across the phrase “protective of his work.” It had struck him as the height of banality at the time, but for that very reason the kind of thing someone who “fell in love with a book” would probably take to. So he wrote an email using the phrase “protective of my work” and promised to send the book when it was finished.

He went out for a beer, because it was restful hearing the Austrians rattle words off their sharp metal tongues. He was gone for some time.

When he got back — it was four in the morning or so — he found the phrase had hit the jackpot. Not only had Ralph taken to it, he had been galvanized into talking about the few magical pages in hand to everyone he knew. A magazine had offered $5,000 to publish them as a self-contained story. “I understand that you are protective of your work” — it was a lucky thing that this was conveyed in an email rather than over the phone, as it did not matter that he burst out laughing — “but it would be a real wake-up call for publishers.” A number of startling proposals followed: if authorized to do so, Ralph would ask the publisher of the novellas and stories (long out of print) to “revert the rights,” so that they could then be “bundled” with the new book when put up for auction. This would then trigger a push to translate the five novels immured in their native Dutch; the 1,000-page killer whale could be the next 2666!

Of course, this is the European fantasy of an American. When other languages need a word for a go-getter they use the word “go-getter,” which is the quintessential American thing to be.

If you have been insane there are so many things you can’t do.

He was able to write a brief email of thanks and acceptance. He felt that he should say something along the lines of Dear Ralph, This is very exciting, but this he was not able to do.

Based on the two pages he had read, he was not a big fan of 2666.

He went outside and smoked a Marlboro.

He went inside and downstairs and lay down on the white bed.

Ralph too had seized on a phrase, “the next 2666.”

He used the phrase in an impetuous conversation with Cissy, who said, “Oh, I didn’t know you knew Dutch.”

“No no no,” Ralph said hastily, impatiently. “Something tells me I’m on the right track. For God’s sake don’t mention it to anyone who does, it might get back to the Eldridges. I’m just wrapping up reversion of rights, we don’t want them going behind our backs to Meulenhoff and picking up something else on the cheap.”

“Oh, okay,” said Cissy. Maybe there was an article on Words Without Borders or something.

Ralph made a vague soothing affectionate noise about her book and got off the phone and was soon talking to Rachel, who had seen the pages and loved them.

“Oh,” said Rachel, “I loved 2666.”

She did not ask if he knew Dutch or had even actually read 2666 because Ralph, the thing he could do was build castles in the air and get people to buy them. If he could build a castle in the air for Peter Dijkstra the genius would fly on a magic carpet.

“I know he’s protective of his work,” said Ralph. “I understand. And I would never do anything to jeopardize the creative process. The work must come first.”

Rachel made a vague soothing affectionate noise.

He said, “But sometimes there’s a moment when people get swept away, and if you miss it you’re fighting against the fact that it’s somebody else’s moment. I think this is his moment. This may sound crazy, but I think if I could even just get all the notebooks in a room, and let a few select people see them, that would be enough to do a deal. Right now there just isn’t enough. Not in today’s climate. But if they see there’s something substantial actually there, if the quality is there, no, I think that would work. But of course, aaargh, I can’t ask him to send the originals and copies are impossible so the only solution would be to bring him to New York but I know, I know, I know, he’s a very private person, how can you throw someone like that into the media maelstrom?”

All this because Rachel had apprenticed to a master of the vague soothing affectionate noise.

Peter Dijkstra lay on a very white bed with his head on his arm.

This would not do.

The go-getter had emailed him several times reiterating that the work must come first. Each iteration came with the rider that if there was anything else he felt able to show, anything at all, they could take advantage of a moment which might not come again.

He leapt suddenly to his feet. He took the notebook from which text had been typed and the file cards from which words had been strung together in the notebook. He placed them in his satchel. He left his room, took the stairs three at a time, strode through the breakfast room and out into the street and around the corner to a shop that sold stationery. He purchased a padded envelope. He placed notebook and file cards in the envelope.

As an afterthought he snatched up a postcard with a photograph of Empress Elisabeth of Austria (“Sisi”) and wrote painstakingly on the back: Dear Ralph, This is how it starts out and it has to stay where it starts out until it is ready to end. Regards, P.D.

He sealed the envelope, addressed it, strode storklike to the post office, paid postage for a method of delivery that was a little faster than normal without being exorbitant, handed over the envelope, and strode storklike to the street. His head was not at all good but he was not positively stalking down the street saying out loud “When you say you know the work must come first what exactly do you mean?” That was something.

It was also something that he had not written Erbarmung!!!!!!! Erbarmung!!!!!!! on the postcard.

It can’t be a good idea to implore an agent with heartrending appeals to Parsifal.

He lit a Marlboro.

Gil sat on the squashy old sofa, legs akimbo, forearms on thighs. He was wearing a very soft faded bluish T-shirt on which dolphins frolicked around the words DAYTONA BEACH FLORIDA and soft faded frayed cutoffs. Rachel sat at the other end of the sofa; she wore the SUDO MAKE ME A SANDWICH T-shirt and soft faded white cutoffs, also frayed. Both were barefoot.

On a battered oak coffee table in front of the sofa were: twenty-odd pages of double-spaced type; a basket of bagels with cream cheese and lox; a cafetière of very black coffee; a carton of half-and-half; a carton of grapefruit juice; a few cans of San Pellegrino with orange; a large bottle of Gerolsteiner. Plates, glasses, mugs, knives. Gil had suggested getting together over a late breakfast because he did not feel comfortable drinking vodka in front of Ralph.

A squashy old armchair, brother to the sofa, awaited Ralph. Meanwhile they were alone.

Ralph was late, late enough for Gil to start to hope he would not come.

“This is probably going to sound really precious,” said Gil. “But I’m not comfortable with this.”

“It’s not precious,” said Rachel. “Nobody is comfortable with Ralph. I mean, I only got into coding in the first place to keep myself sane. I would get off the phone after one of these marathon sessions and just tie myself to Boolean logic like a mast. And now that I have Barbara, she’s so professional and businesslike, she’s like a rock. But maybe. He was in an asylum all those years. If he had a whole book he could take it to Barbara, and it could be all right. But he doesn’t have a book. And anyway there would still be the whole thing of getting people whipped up to a frenzy over a Dutch writer, and the whole point of Barbara is she doesn’t do frenzy. So maybe frenzy is the price he has to pay to stay in this place Cissy found instead of an asylum. I mean, it could just be that way.”

“I guess.”

This was what he had always liked, she could sail effortlessly uncomplicatedly through. But he did not think he could tell lies for Peter Dijkstra, and he did not want to find himself somehow underwriting a book in Dutch he had never read as the next 2666.

The coffee was unreproachfully tepid.

Now that Ralph was living one day at a time he would often spend hours talking some poor desperate soul out of a crisis. You would arrange to meet and find yourself catching up on Dinosaur Comics on your iPhone, checking the time, catching up on A Softer World, checking the time, wondering whether there was anything new (please say yes, God, please) on Perry Bible Fellowship, getting a 503 Service Unavailable!!!!!!!, scouring around online to see whether this was permanent or what?????!!!!!!, noticing the time, only to have Ralph walk belatedly in or text or call to explain that Dale or Jane or Andy was suicidal and he had to be there for them. Not that Gil wanted any extra person to be suicidal, but if someone was suicidal anyway and Ralph had to be there for them rather than here for him it would Be. So. Great.

But no, the buzzer buzzed.

Ralph came eagerly down the long room in a glow of happiness, this Tom Cruise “I am a Thetan!!!!!!” kind of glow which, okay, somehow this was less creepy in the days when you knew he was doing drugs? But okay, okay, okay.

He wore a tan polo shirt with a crocodile on the breast, chinos, and sockless Topsiders, because he had never wanted to be a suit.

He took a padded envelope from his bicycle bag. “Here,” he said, eyes ablaze. “I’m sorry I’m late but when you see you’ll see.” He put it at the midpoint of the squashy sofa and sank into the squashy chair. (It was kind of like Joseph Smith presiding over the display of a golden tablet from the Book of Mormon.)

Gil did not touch the envelope. Rachel picked it up and removed a notebook and a pack of some seventy file cards. She handed the notebook to Gil and began reading through the grid-ruled file cards, one by one.

Ralph gave them a lot of space to read in silence. It was weird holding in your hands things that had been in the hands of Peter Dijkstra, as if the Van Gogh Museum would let you take a painting off the wall. It was kind of weird holding them with Ralph expectantly watching — but no, Ralph suddenly noticed the cold thing of coffee and said ruefully “I am late, I’ll make fresh” and went off to the kitchen, so fine. Fine.

It’s true. You definitely got the feeling, holding these objects, that they had been in a room with a crazy guy, or rather a guy with the potential to be crazy who was trying to keep madness at bay. The writing was small and precise and clear, this slightly pedantic European handwriting that you would normally never see. Reading a typescript, you would miss this: it was like hearing excellent English spoken with a foreign accent. You saw the effort that had gone into the excellence. Precision, a bulwark. (The word “bulwark” was in fact on one of the cards.) You could see that maybe the visibility of the effort had to stay there for the completion, or even the continuation, of the work.

Ralph came back with fresh coffee.

Rachel put each file card back at the midpoint of the sofa as she finished it.

Ralph did not return to the squashy chair. He poured himself a mug of coffee and wandered tactfully off to browse bookshelves.

An experience you tend not to have at the Van Gogh Museum is of a security guard wandering tactfully off and rummaging through your backpack while you are staring your eyes out at paintings you have seen only in books and calendars and posters.

In some kind of weird activation of peripheral vision Gil not so much saw as sensed Ralph pausing by the eighteen inches of shelving dedicated to Peter Dijkstra. Which was a good thirteen inches more than were taken up by the stories and the novellas.

Gil had met Rachel in the gift shop of the Van Gogh Museum in the heat of the hype. She had picked up a paperback, Vincent van Gogh, een leven in brieven. He had seen her across a room but kept his distance. If you have never been to Amsterdam before and maybe never will be again you don’t want to smear the paintings with a lot of boy-meets-girl stuff. There were paintings on the walls that had been in a room with a crazy guy, a guy who never sold any paintings; you want to be alone with the craziness. He walked from room to room, seeing her across each room, keeping his distance.

The gift shop did seem like this space designed to ease the transition to the world of men.

She saw him and held up the book and smiled. (They had been so many places at the same time, it was like running into someone at the mall who was in five of your classes.) He asked if she knew Dutch. She said, “No, but maybe it’s better that way. It’s as if there were special words for colors that nobody else had ever used. Koningsblauw — I don’t even know how you say it, but maybe I just want to know it exists.” She showed him a page on which he saw the word Sterrennacht.

They did not agree to leave together but they left together. As they passed a bookshop Gil said “Wait!” and ran in and bought five books by Peter Dijkstra that had not been translated, because Gil might never be in Amsterdam again and he had to have them. If he had not met her it would never have occurred to him to buy books he could not read and probably never would and yet had to have.

Neither of them was stupid enough to tell anyone, even close friends, because you never know who will say something to someone and then it is out in the world, something that meant something all cartoonified and fatuous. But he looked at the pages of the notebook and thought of the Van Gogh Museum and keeping his distance and running in to the bookstore.

He did not want to share this with Ralph and he also did not want Ralph to leap to conclusions re his apparent immersion in the oeuvre and suddenly it seemed it had to be one or the other.

Gil finished the notebook before Rachel finished the file cards. He put it at the midpoint of the sofa and picked up the file cards she had finished and when she had finished the file cards she picked up the notebook and when they had both finished they put the things in their hands back at the midpoint of the sofa.

Ralph returned to the squashy chair. “You see,” he said simply. “You see.” He said he had emailed Peter and asked how many more notebooks there were and there were about fifty. (It was weird hearing him called “Peter.”)

He talked again about the moment and what he could do if Peter Dijkstra and his notebooks were brought to New York.

If Ralph had not been there they would have gone on passing the notebook and file cards back and forth in silent wonder. Or maybe one would have said, “Look at this,” and the other would have said, “Look at this.”

Ralph went on being there.

Instead of “Look at this” they got stuff like, the longer there was no actual deal, no major player with an option on the backlist, the greater the danger that someone would snap up the next 2666 for peanuts.

Gil stood up. He padded down the room to a shoe rack from which he took a pair of socks and a pair of Timberland boots which he slipped on before opening the door. Turning.

He said, “I’m sorry, but I can’t — This is too important for me. It would mean a lot to see the other notebooks, if he was willing to show them. If you think it would help, I can pay his airfare to New York and he can stay in the loft and you can show people the notebooks in the loft if that helps and I will move in with Rachel until it’s over. But I can’t do this other stuff and I can’t talk about this anymore.”

He closed the door behind him.

“Oh God,” said Ralph, “I didn’t mean —”

Rachel made a vague soothing affectionate noise.

Striding barelegged and booted down Vestry Street, down Hudson, Gil had this sudden paranoid image of the fifty notebooks, these van Goghy things, these things it would be transcendent to sit quietly down with, on a big table in his loft with the five Dutch books placed inconspicuously by as if to imply without Gil even saying a word that he had read them in the original Dutch (such being his fanatical devotion to the genius) and could vouch for King Kong being the next 2666. This or that editor being ushered in and not even having the books pointed out by Ralph because they’d just quietly accidentally be there. But this was totally paranoid, right? Right? Because nobody would do something that icky, would they? Would they? Or should he take them to Rachel’s to be on the safe side? Or would giving in to paranoia make it worse? Or —

The Timberlands had propelled him east on Worth. They crossed West Broadway, turned south. He was just thinking that maybe he would do something totally normal such as go to Edward’s for a hamburger and fries, Edward’s being a block away, when he saw, sitting dreamily outside at Edward’s, Miss Total Weirdness. He sidestepped into the nearest doorway. Which turned out to be that (the Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want) of a bar. It was maybe not totally normal to have a double vodka at 12:02, but fuck it.

One of the very few benefits of fame was that the bartender recognized him, so it did not matter that he had come out without any money.

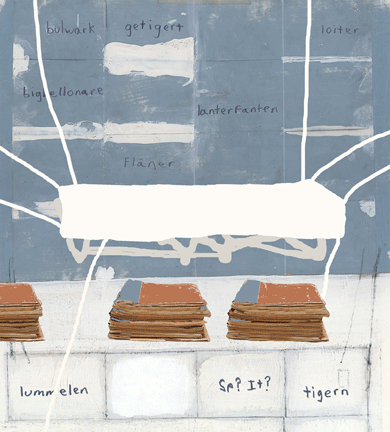

Peter Dijkstra had recently discovered a nice fact. There is a German word, getigert, for a cat with striped fur. This immediately transforms one’s view of the animal. (This small domestic tiger.) This had led to other nice facts: the verb tigern means an activity which corresponds to the English words mooch, loiter (this on the authority of pons.eu), the French flâner, all surely with radically different connotations from the Dutch word lanterfanten. A lord of the jungle, off the prowl, proceeding as chance takes him velvet-pawed through his domain, twitching his lordly tail — this is quite different, clearly, from, well, lanterfanten is also the word which goes into the English for fiddle while Rome burns. And a flâneur, this is Baudelaire, this is an inhabitant of Walter Benjamin’s Passagenwerk, The Arcades Project. Jeepers!

He wrote getigert!!!!! on one file card and tigern, mooch, loiter, flâner, lanterfanten, and lummelen on another. At the bottom of the second file card he wrote Sp? It? And, presently: bighellonare?

Gil ordered a second Potocki and took it to a booth. (He loved booths. But who doesn’t love booths?)

The notebooks had, maybe discomfort isn’t something you can crystalize, but he felt really uncomfortable.

When he had read Rachel’s first book it was not exactly whether it was good or bad, but he wanted to feel he knew the most important thing about her, that every single detail was something she had picked out of the world. But the genius could not be in the details because the details were exactly what Ralph prided himself on attention to. So any detail could always have displaced some other detail, which was the detail Rachel had chosen before the detail attracted attention. How could someone just casually displace that? This was a guy who would pay $50 more to have a crocodile on a polo shirt. To say that it wasn’t even that he liked crocodiles would be to miss the point, there was no way he would wear any shirt with a crocodile motif even if he did like crocodiles, or any shirt with any motif, unless it was an emblem you had to pay $50 more to have on a shirt.

This had been, maybe “inchoate” is the word. For the unease. (Which was now, what, choate? Really?) He had thought he loved Peter Dijkstra’s work when he read the novellas and the stories, but when he saw the notebook and the file cards there was this sudden jolt, because this was English that Peter Dijkstra had actually picked and it was different from the English people had picked to share Peter Dijkstra with English readers.

Which was not a problem in itself, because there had always been Dutch words behind the English words someone had picked. Whereas.

Cissy did not want to be paranoid but she sensed that there was an inner circle and she was not in it. Adam did not want to be paranoid. Ellen did not want to be paranoid. Merrill did not want to be paranoid. That is, Cissy sat over steak and frites at Edward’s, Adam had an omelette ardennaise and a Leffe at Petite Abeille (he adored Tintin), Ellen was just mooching up West Broadway toward a grilled cheese on rye at the Square Diner, Merrill was heading for a TBA brunch at the Odeon when they saw Gil duck into a bar, and fame being what it is all four thought he was avoiding them. Fame being what it is a devotion to the work of Peter Dijkstra had looked briefly like the ticket to an inner circle, and now look. It was horrible. It was false to everything that had ever mattered about Peter Dijkstra.

Cissy was the one who had followed her instincts and found herself in a hotel like a monastery, independently chosen by Peter Dijkstra. Oh, she should go back to following her instincts. She should be true to herself. Passing through Berlin she had seen a restaurant in the Daimler showroom on Unter den Linden; she had thought of having Breakfast at Daimler’s and laughed out loud but there was a plane to catch, why had she stupidly caught that plane? She would go back to Berlin and have Breakfast at Daimler’s every day among the gleaming classic cars until she had written a book as fast and sleek and gleaming as a Daimler.

Adam had found a place in Cappadocia where the people lived in caves, and later, beached in New York, found it independently singled out in a PD novella. Why had he left? He would go to Cappadocia and live in a room in a hotel in a cave until he had written a book of cave dwellers in a wind-washed land.

Ellen had once missed a flight in Istanbul and spent twelve hours in the food mezzanine, an expanse of white plastic tables as far as the eye could see. There was a Burger King and a bar and a deli serving authentic Turkish food, and that day among the white tables was the best of her life. Why had she stupidly boarded her plane? (Peter Dijkstra would not have boarded the plane.) She would go back to Istanbul and stay at the airport and write a book as unencumbered and directionless as a room of white plastic tables.

Merrill had once stayed in a worn-down hotel in Paris, the Hôtel Tiquetonne, in a tiny room on the seventh floor, and he had been happy. Peter Dijkstra would have stayed, taking the creaking elevator with its accordion iron door. He would go and he would write a book as lighthearted in a worn-down world as a room in a downtrodden hotel on the seventh floor.

Perhaps this was not what Ralph had in mind when he talked of the passing of the moment, and yet the moment was passing.

Gil felt the confines of the inner circle closing in around him.

The way to be true to Peter Dijkstra was to be true to himself.

A loft and stuff is the kind of thing that fits into the transaction of the gift, you can transfer, bestow. But not having a loft and stuff, solitude, silence, being alone in a room with a notebook, if you have these things you can’t give them by transferring or bestowing.

Peter Dijkstra was in this four-room underground hotel in Vienna and he had filled fifty notebooks and if he could fill fifty notebooks why would he want to do anything but stay in the underground hotel filling notebooks? Why would he want a loft and somebody else’s stuff?

But what if?

What if the normal rate for a room at this underground hotel is $79 a night, BUT, you could get a room with notebooks & file cards on loan from Peter Dijkstra for $299 a night, and the $220 goes to Peter Dijkstra. So he can keep his room indefinitely because it is paid for out of lending out his notebooks &c. AND. There are SEPARATE ENTRANCES. So you NEVER SEE Peter Dijkstra. He uses one entrance and you use another, so he can go on working without interruption, and you can sit in your room with the notebooks.

It would be great if you knew Peter Dijkstra’s favorite restaurants. People go to the restaurant and they can just order a meal. Or, they can order a meal plus notebook & file cards for the cost of an extra meal, which is left on account for Peter Dijkstra. Who can turn up whenever he wants and find his meal is already paid for!

Gil could totally see himself going to a restaurant and ordering a meal and a notebook and paying extra for the notebook. It would be better than going to a restaurant and having a meal with Peter Dijkstra and paying for the meal because there was no reason to think words from the mouth would have the intensity of the ink on the grid.

He asked the bartender for a napkin and a pen, and he scribbled down the ideas in their brilliance as fast as they came.

He would write a book in which people did not destroy the thing they loved.

Peter Dijkstra got an email from the go-getter the gist of which was that the notebook and file cards had struck a bonanza. A young writer who worshipped his work had offered the use of his loft and airfare, and if he would take his notebooks to New York, editors would make an exception and read the work in this unpolished state and the go-getter could virtually guarantee that they could get a deal on the strength of this and set the ball rolling.

He got an email from the young American proposing schemes which seemed to involve encouraging total strangers to descend on his hotel and favorite restaurants and go through his papers.

He got emails from one young American after another who had learned to be true to themselves.

Peter Dijkstra had been sitting at the small desk in his room. He stood up, stretched. He left the room, went upstairs and went out into the street. It was not a very nice street: one good thing about the rooms was the fact that they had no view.

He could not think of anything to say in reply to the emails. Or rather, what he wanted to say was, “I’m a very good man, but I’m a very bad wizard.”

He lit a Marlboro and went off in search of a beer or maybe a Sachertorte or a schnitzel. He could not say which verb described the movement of his aimless feet.