Cliven Bundy, the notorious scofflaw cattle rancher from Bunkerville, Nevada, was taking his midday nap when I arrived at his spread. One of his daughters — he has fourteen grown children, and they all seemed to have mustered at the ranch — told me that the nap was “very important” and our two o’clock appointment for an interview would have to wait for “whenever he wakes up.” I passed the time in the shade of the trees in his yard and talked with his militiamen, who looked miserable in the heat. They were awaiting an ambush by agents of the federal government, whose most oppressive arm, they assured me, was the Bureau of Land Management, a branch of the Department of the Interior. From across the country the militia had come to “make war” on the BLM, which manages more public land than any other federal agency.

In April 2014, three weeks before my visit, the BLM had begun to impound Bundy’s herd, which had been illegally grazing on a 578,724-acre parcel of public land in the Mojave Desert known as the Bunkerville Allotment of the Gold Butte range. The BLM planned to sell the herd in order to reimburse the public for an estimated $1.1 million in grazing fees and fines that Bundy owed. Bundy, decrying federal tyranny and vowing to do whatever it took to protect his rights to graze his cattle, called in the press to witness the start of a “range war” on Gold Butte. On April 9, a few days after the roundup began, one of Bundy’s sons was shocked with a taser after he attacked a BLM officer. Video of the conflict was posted on YouTube and became a right-wing cause célèbre. Fox News showed Bundy parading in his white hat, on his white horse, carrying an American flag that billowed in the Nevada wind. At least a hundred men and women converged on Bundy’s ranch, anticipating the next Waco. They brought with them semiautomatic handguns, large-bore revolvers, assault rifles, and don’t tread on me flags.

People began calling the BLM with death threats. Bundy supporters tweeted the home address of a former U.S. Forest Service biologist now working for the Center for Biological Diversity, a nonprofit that monitors conditions on Gold Butte, and threatened his family. The FBI told him to leave his house. BLM managers who had no law-enforcement training — biologists, ecologists, rangeland conservationists — took to carrying pistols as personal protection for the first time in their careers. Employees in the field were warned to pair up and to go nowhere on Gold Butte without alerting their superiors.

On April 12, a crowd numbering in the hundreds shut down Interstate 15 in both directions. Snipers from Bundy’s militia took positions in the thorny scrub along the highway. A group of Bundyites on horseback rode down a hillside to face the BLM rangers. There were fingers on triggers on both sides. “If a car had backfired,” a militiaman told me, “the shooting would have started.”

The standoff ended, however, without bloodshed. On the morning of April 13, the BLM announced that the removal of the herd would immediately cease, owing to “threats to public safety.” It was another defeat for the federal government in a conflict with Bundy that has lasted more than twenty years. In 1993, the BLM took the modest step — to Bundy an unconscionable one — of modifying his grazing permit to reduce the overstocking of Gold Butte, citing the damage his cows were causing to the fragile habitat of the threatened desert tortoise. Bundy refused the permit modification, quit paying his fees, and, in an act of pique, turned out more than nine hundred animals onto the allotment — almost nine times the number stipulated by his permit. The BLM did not intervene, though it did cite him for trespassing and noted, in a series of environmental studies, that the overstocked cattle, which had filled the riparian areas with dung and urine and gorged on what little grass was available, were wreaking ecological havoc.

In 1994, the agency ordered, with the decorum of administrative process, that Bundy remove the cows. One of his sons tore up the notification in front of the BLM officers who delivered it to the ranch. Bundy then attempted, absurdly, to pay his grazing fees to Clark County, which could not accept the money, since it had no jurisdiction over federal land. In 1995, the BLM again ordered Bundy to remove his cattle. Bundy again said he would not, and the BLM again delayed further action. The courts weighed in. The Department of Justice filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for Nevada, which in 1998 found in favor of the government, a decision upheld by a federal appellate court a year later.

There the matter remained for another decade, the trespassing cattle roaming and ranging, the land and tortoise habitat “beaten to shit,” in the words of a local biologist. The case languished in the Department of Interior until 2008, when the Board of Land Appeals affirmed the cancellation of Bundy’s permit. Bundy countered with a letter that asserted his rights to public land and demanded state and county law enforcement “perform their Constitutional duties.” He concluded with a proclamation: “In the name of Jesus Christ I stand immoveable for Liberty.” The BLM pondered the situation for another three years, while Bundy’s cattle wandered onto adjacent lands that were managed by the National Park Service and the Nevada Department of Wildlife. In 2011, the BLM issued a cease-and-desist order along with a notice of intent to eject the offending cows. The agency waited another year before directing its Nevada employees to prepare for a roundup. In July 2013, the district court ordered Bundy to remove his cattle within forty-five days. Bundy told local newspapers that he didn’t recognize the court’s jurisdiction. Another nine months passed before the BLM got up the courage to impound his herd.

When Bundy awoke from his nap, I was listening to his grandson pluck a guitar. The patriarch emerged sleepy and soft-spoken, childlike, wearing his white Stetson, thick-heeled boots, and a blue-check button-down shirt tucked neatly into jeans that were held up with a big brass buckle. He offered me a plate of Bundy beef. A cowboy bodyguard, with a pistol at his hip, hovered nearby as Bundy and I talked under the shade trees. I asked him to justify his claims to the Gold Butte allotment. He told me that the U.S. Constitution — a copy of which he kept in the breast pocket of his shirt, over his heart — held all the justification he needed. Under the Constitution, he said, there could be no such thing as federal public lands. Given this fact, the states, or better yet the counties, should control the land currently claimed by the U.S. government, and the entire federally managed commons should be abolished. He patted his breast and referred me to Article 1, Section 8, Clause 17, which, he said, limits the amount of land that the federal government can own to ten square miles. (It does no such thing, though it does establish that Washington, D.C., should be limited to ten square miles.)1 Bundy went on citing the sacred document for the next thirty minutes, earnest and impassioned, as I tried and failed to interrupt. Then, yawning and adjusting his big hat, he excused himself to go inside the house. I waited, lounging in a lawn chair, expecting that he might want to talk some more.

I had planned to ask Bundy why he was complaining about a government that had been so patient with his shenanigans, one that subsidized ranchers like him with enormous largesse. This was a government, I wanted to remind him, that had set the federal grazing fee at $1.35 a month per cow-calf pair when the market rate on private land averaged $11.90, and it was spending at least $500 million annually in direct and indirect subsidies for public-lands ranchers. (In an essay for this magazine that was published in 1986, Edward Abbey called Western cattlemen “welfare parasites.”)

While I waited for Bundy to reappear, I watched another of his grandsons rope a dummy bull for rodeo practice. Finally, after half an hour, the bodyguard stood over me and grimaced, his hand on his holstered gun. “All right, that’s it, time to go.” I hesitated; the bodyguard shook his head. “I think he’s gone back to sleep,” he said. “The man needs his naps.”

In 1885, William A. J. Sparks, the commissioner of the General Land Office, reported to Congress that “unscrupulous speculation” had resulted in “the worst forms of land monopoly . . . throughout regions dominated by cattle-raising interests.” West of the hundredth meridian, cattle barons had enclosed the best forage along with scarce supplies of water in an arid landscape. They falsified titles using the signatures of cowhands and family members, employed fictitious identities to stake claims, and faked improvements on the land to appear to comply with the law. “Probably most private range land in the western states,” a historian of the industry concluded, “was originally obtained by various degrees of fraud.”

The cattle barons were not cowboys, though they came to veil themselves in the cowboy mythos. They were bankers and lawyers, or mining and timber and railroad tycoons. They dominated territorial legislatures, made governors, kept judges, juries, and lawmen in their pockets. They hired gunmen to terrorize those who dared to encroach on their interests. They drove off small, cash-poor family ranchers by stampeding or rustling their herds, bankrupting them with spurious lawsuits, diverting water courses and springs, fencing off land to monopolize the grass, and, finally, when all else failed, by denouncing the subsistence ranchers as rustlers who should be lynched. By the late nineteenth century, the barons had privatized the most productive grasslands and the riparian corridors, where the soil was especially rich. What remained was the less valuable dry-land forage of the public domain, which by 1918 totaled some 200 million acres spread across the eleven states of the West, and which the barons also dominated by stocking them with huge numbers of cows.

Overgrazed and underregulated, the public rangelands descended into a spiral of degradation, the grass in ruin, the topsoil eroded by rain or lifted off by the wind. Only in the 1920s did Congress take serious notice. Ferdinand Silcox, the chief forester of the U.S. Forest Service, testified in 1934 that unregulated grazing was “a cancer-like growth.” Its necessary end, Silcox said, was “a great interior desert,” a vast dust bowl.

Congress’s answer was the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934. The legislation established fees for grazing rights and created what was to become the U.S. Grazing Service, a regulatory apparatus “to stop injury to the public grazing lands.” From the start, though, the regulators were compromised. “What did the Grazing Service do?” Representative Jed Johnson of Oklahoma asked. “They went out and turned [the land] over to the big cowmen and the big sheepmen of the West. Why, they even put them on the payroll.” It was commonplace to find range regulators who were the sons, grandsons, cousins, or old friends of ranchers they were supposed to regulate — if they weren’t ranchers themselves.

This culture passed seamlessly to the Bureau of Land Management, which was created out of a merger between the Grazing Service and the General Land Office, in 1946. That same year, members of the American National Livestock Association met in Salt Lake City to discuss how best to undermine what few regulations had been placed on them. The Taylor Grazing Act had made grazing permits revocable. The livestock-permit holders wanted this provision overturned, for obvious reasons. But the stockmen’s ambition went further: they wanted the federal government to transfer control of all federal land, including the national parks, to the states.

The historian Bernard DeVoto covered the story for this magazine, cautioning that the livestock industry was attempting “one of the biggest land grabs in American history.” The public lands “are first to be transferred to the states on the fully justified assumption that if there should be a state government not wholly compliant to the desires of stockgrowers, it could be pressured into compliance,” he wrote. “Nothing in history suggests that the states are adequate to protect their own resources, or even want to, or suggests that cattlemen and sheepmen are capable of regulating themselves even for their own benefit, still less the public’s.”

The push for state ownership of public lands was part of a larger ideological struggle, DeVoto concluded, “only one part of an unceasing, many-sided effort to discredit all conservation bureaus of the government, to discredit conservation itself.”

A week after I met with Bundy, members of his clan, led by his son Ryan, drove six hours east to the town of Blanding, in the canyonlands of southern Utah, to attend an anti-BLM rally. Armed and hostile, Ryan and his contingent joined at least 250 people gathered in the town square, most of them Blanding residents. Blond schoolgirls with wide smiles handed out pocket-size copies of the Constitution, which the protesters kept, à la Cliven, in the breast pockets of their shirts.

The organizer of the event, a county commissioner named Phil Lyman, told the crowd about the tyrannical behavior of the BLM: In 2007, rangers had closed portions of nearby Recapture Canyon to motorized traffic. The BLM had determined that the unrestricted use of all-terrain vehicles and jeeps in Recapture had resulted in the trampling of “a rich archaeological record of the Ancestral Puebloans” who lived in the canyon 1,000 years ago.

Access to the canyon wasn’t the issue, as Lyman admitted. There were thousands of miles of canyon trails around Blanding that were open to off-road vehicles. Rather, Recapture Canyon was a symbol of oppression, and now, seven years after its closure, San Juan County needed to act. “This protest is not about Recapture, or about ATVs,” Lyman had written on his Facebook page; “it is about the jurisdictional creep of the federal government.”

Lyman’s original plan was for the citizens to ride their A.T.V.’s en masse into the closed canyon. But now he hesitated, and suggested that the protesters should enter the canyon but only motor to the boundary of the closure. He worried that the action was “looking like conflict for the sake of conflict.”

The Bundyites revolted. A woman shouted, “The BLM ruins the land!” There were denunciations of “the BLM police state” and comparisons to the Gestapo. There was talk of revolution. “You’ve got guns, too. By God, that’s what they’re for!” a man cried out. Ryan Bundy, imperious in his black cowboy hat, his Constitution poking out from his plaid shirt pocket, took the microphone and set matters straight. “I came here to open a road,” he said, with a glance at Lyman. “And if we aren’t going to do that, I’m going to get in my truck and go home. If we’re going to talk about public land, it’s not the public of the United States, it belongs to the public of San Juan County.”

The crowd roared, and the protesters rushed to their waiting A.T.V.’s and jeeps. They drove in a column to the mouth of Recapture Canyon, where they descended into the gorge, their engines grinding and whining, the air filling with dust. Ryan Bundy rode his A.T.V. with his dazed toddler son on the seat in front of him. He saluted as he crossed the closure boundary, while a crowd stood by waving American flags. They repeated the phrase “Thank you, sir!” to each passing rider, some of whom cradled assault rifles. The only law enforcement on hand were some local sheriff’s deputies. I asked one of the deputies whether he or his fellow lawmen had done anything to stop the incursion. He laughed and said it wasn’t their job, it was the BLM’s. I asked whether he’d seen BLM officers. “Not one,” he said. “Complete no-show.”2

One could write a postwar history of the West as a chronology of ranchers’ resistance to federal regulation, and the center of resistance has always been Nevada. In 1979, following the passage of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, which for the first time mandated environmental protection of territory controlled by the BLM, cattlemen pushed a law through the Nevada state legislature declaring that federal public lands were now the property of the state. They called it the Sagebrush Rebellion Act. The cattle barons styled themselves “sagebrush rebels,” and engaged in acts of defiance against the BLM, opening dirt tracks onto grazing allotments that had been closed, bulldozing new roads, overstocking their allotments, violating permit agreements, and refusing to pay grazing fees. As the rebellion spread, a conservative interest group called the American Legislative Exchange Council joined the fight. ALEC was founded in 1973 to craft “model legislation” for state governments; it brought together conservative state legislators and industry representatives in closed-door sessions. Copycat Sagebrush Rebellion Acts were passed in Utah, Arizona, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

In the past thirty years, ALEC has thrived: 27 percent of all state legislators are now members. Its corporate advisory board includes ExxonMobil, Altria, and Koch Industries. In addition to its work fighting federal ownership of public lands, ALEC has helped states to pass stand-your-ground laws, to privatize public education, and to implement ag-gag rules.

A tumbleweed near hoof marks on a grazed patch of Jarbidge BLM land in Idaho. Photograph by Tomas van Houtryve

On April 19, 2014, one week after the Bundy standoff, some fifty Republican state lawmakers, from nine Western legislatures, convened in Salt Lake City for what they called the Legislative Summit on the Transfer of Public Lands. The conference was organized by Ken Ivory, a Utah state representative, and Becky Lockhart, the speaker of the House in Utah: both are members of ALEC. Ivory had sponsored Utah’s Transfer of Public Lands Act, which was passed overwhelmingly by the state legislature in 2012. At the summit, Lockhart called the Bundy affair “a symptom of a much larger problem” — the problem being that federal public land exists at all.

The ALEC agenda has also found its way back to Congress. The vehicle has been the Republican leadership in the House Committee on Natural Resources, which controls the Subcommittee on Public Lands and Environmental Regulation. The bills proposed in the most recent congressional session speak for themselves. The State-Run Federal Lands Act, sponsored by Representative Don Young, a former ALEC member from Alaska, authorizes federal-land managers to “enter into a cooperative agreement for state management of such federal land located in the state.” The Disposal of Excess Federal Lands Act, sponsored by Representative Jason Chaffetz of Utah, directs the secretary of the interior to “offer for disposal by competitive sale certain federal lands in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming.” With Republicans now in control of both the House and the Senate, these bills have a good chance of passing.

Recently I spoke with the ranking Democratic member of the natural-resources committee, Representative Raúl Grijalva of Arizona. “We are seeing bills that begin to tear at the fiber of law on the federal public lands,” Grijalva told me. “These laws would allow state law to supersede the federal government.” In 2013 and 2014, the Subcommittee on Public Lands and the Environment held a number of hearings in which witnesses “carrying the ALEC agenda,” in Grijalva’s words, attested that the states do a better job at managing public lands than the federal government. “But the states don’t do a better job,” Grijalva told me. “We know that. These hearings keep pounding the agenda into the record — they are redundant — and then you get to the point where you have congresspeople saying, ‘Well, we’ve had six hearings on this, let’s start to craft legislation.’ The chatter is deliberate and persistent.”

Last April, Grijalva asked the acting inspector general of the Department of the Interior to “investigate the role of [ALEC] in efforts to pass bills at the state level that directly contradict federal land management policies and directives, and to assess the extent to which these efforts have affected Department of Interior personnel.” Grijalva worried that “ALEC’s pattern of activity raises serious questions about how changes to land management laws and regulations, especially in the Western United States, are being pushed by ALEC without public disclosure of its role or that of the corporations that fund its legislative agenda.” He noted that ALEC’s positions are “entirely consistent with the position taken by anti-government rancher Cliven Bundy and his armed supporters.”3 One of ALEC’s model bills is the Eminent Domain Authority for Federal Lands Act, which, like Bundy, cites Article 1, Section 8, Clause 17 of the Constitution to justify state seizure of federal land. (A spokesperson for ALEC disavowed Bundy and his actions.)

A cow drinks on a section of the Jarbidge where herbicide spraying, trampling, and the planting of exotic grasses like cheatgrass have destroyed the native vegetation and ground cover. Photograph by Tomas van Houtryve

The wholesale transfer of public lands to state control may never be achieved. But the goal might be more subtle: to attack the value of public lands, to reduce their worth in the public eye, to diminish and defund the institutions that protect the land, and to neuter enforcement. Bernard DeVoto observed in the 1940s that no rancher in his right mind wanted to own the public lands himself. That would entail responsibility and stewardship. Worse, it would mean paying property taxes. What ranchers have always wanted, and what extractive industries in general want, is private exploitation with costs paid by the public.

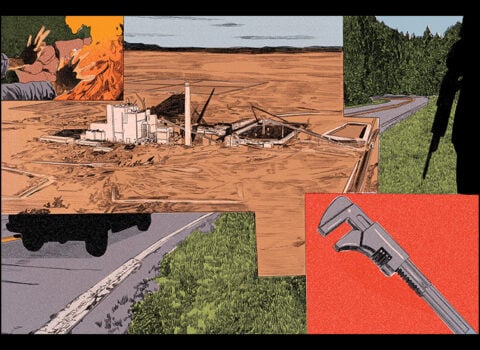

Bundy’s victory in April — which is to say the BLM’s abject defeat — proved to be an inspiration for like-minded Americans. On May 6, two hooded men driving a pickup truck with a masked license plate approached a BLM employee driving a load of horses and burros on a highway near Nephi, Utah. They pointed a pistol at him and held up a sign that said you need to die. The men fled, and were never caught. On June 8, Amanda and Jerad Miller, a young couple from Indiana who had joined Bundy’s militia, burst into a Las Vegas pizzeria and, at point-blank range, shot and killed two police officers who were eating lunch. The Millers draped the dead bodies with a yellow flag that said don’t tread on me and pinned a note to one of them that called the killings the beginning of a revolution. They continued on to Walmart, where they shot and killed a customer. Then, after she found herself surrounded by police, Amanda killed her husband and turned the gun on herself.

Along the canyon edges of Salmon Falls Creek, an area too steep for cows to trample, on the Jarbidge. A macrobiotic crust and thick ground cover are indications of healthy soil, which supports the plant life necessary for sage grouse and other native animals. Photograph by Tomas van Houtryve

In western Utah, a few county commissioners announced that they planned to violate the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act by illegally rounding up herds of wild mustangs that were competing for cattle forage on public land. In June and July, the BLM responded to that threat by rounding up the mustangs for them. On June 14, a California man, who had been posting favorably on Facebook about Bundy’s revolt, shot and wounded a BLM ranger in the Sierra Nevada mountains after he was asked to move from his illegal campsite. On July 1, a group of gold miners descended onto a BLM-managed stretch of the Salmon River in Idaho to dredge the riverbed with industrial suction equipment. The action most likely violated the Endangered Species Act, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, and the regulations of the Environmental Protection Agency, which oversees the ecological health of parts of the Salmon River in partnership with the BLM. The miners were not looking for gold. A spokesman for the Southwest Idaho Mining Association, in Boise, told the Associated Press that the illegal dredging had a single purpose: to drive the EPA from the state.

These incidents, coming one after another, gave the appearance of a metastasizing problem. Bundy, for his part, has been bragging that his ranch has been free of “overreaching government policing agents” since April. In October, the BLM moved to designate an additional 1.8 million acres of land surrounding Bundy’s property as Areas of Critical Environmental Concern, which would make them off-limits for grazing. Bundy called it a “deliberate retaliation.” If the new environmental protections are approved, it remains to be seen if the BLM has the firepower to enforce them.

Last summer I camped on BLM land in the company of a thirty-one-year-old Idahoan named Brian Ertz, the chair of the Sierra Club’s National Grazing Team. Ertz has compiled a gruesome catalogue of the effects on the land when deregulation and lax enforcement are the norm. Grazing is the chief cause of desertification in North America, and it has irrevocably altered the surviving ecosystems not yet reduced to dust. Cattle have been implicated in the eradication of native plants, the pollution of springs and streams, the denuding of cover for birds and mammals, the deforestation of hardwoods, and the monoculturing of grasslands. When the Department of the Interior completed its most recent analysis of the ecology of the public lands under BLM management, in 1994, the overall assessment was dire. The riparian areas in particular were found to be in their worst shape in recorded history. The report produced such a storm of outrage from the public-lands ranching lobby that when the BLM was given $40 million to conduct a similar study, in 2010, it exempted the impact of livestock to placate the ranchers.

I had asked Ertz to take me on a tour of a grazing district on the Idaho-Nevada border called the Jarbidge, which he had described over the phone as “one of the most cattle-fucked landscapes you’ll ever see.” Ertz had grown up in Boise, and as a teenager his backyard was the wilderness of southern Idaho and northern Nevada, the vast Great Basin steppe that ecologists have come to call the sagebrush sea. The shrubby sage, which grows close to the soil, evolved to preserve its moisture against the heat and the wind of the steppe, and to survive the cold, snowy winters. Ertz explained why the sage steppe was called a sea. “Because in the spring the new shoots on the sage, iridescent, light, and soft, bow in the wind and what that creates on the landscape is an evocation of the wind on the sea. And when the wind blows at dusk after the rain, there’s the sweetest smell.” The sage that held the soil in place created habitat for native flowers and bunchgrasses, and those flowers and grasses fed the native ungulates — elk, pronghorn antelope, mule deer — and those ungulates fed the great predators of the West, the wolf and the cougar and the grizzly. The sagebrush sea, Rachel Carson wrote in Silent Spring, was “a natural system in perfect balance.”

A cluster of grass roots on the Jarbidge. When grass is overgrazed, it can lose its grip on the soil and fail to regenerate. Photograph by Tomas van Houtryve

We pitched our tents at a BLM campsite, and the next day drove on a dirt road into the Jarbidge district to look at an allotment that had once been predominantly sagebrush. I was unprepared for the devastation we saw. When I had lived in Utah, where two thirds of the state’s acreage is managed by the federal government, I had spent a lot of time backpacking and camping on public land, where I found the usual overgrazed valleys and meadows and canyons, the fields without flowers, the meadows without grass, the springs where the cattle had congregated, stomping and trampling, churning the water to shit-filled muck. But higher in the mountains and deeper in the canyons, I had always found crags the cows couldn’t reach where the streams ran clear and the banks were green.

On the Jarbidge, a cattle-blasted moonscape reached for miles. The grass had been grazed to dirt, the dirt formed dust devils when the wind kicked up, and the land looked hopeless. The sagebrush, which cattle will eat when there is nothing else, was gnawed and withered and bent. We crossed hundreds of acres where the sage had disappeared entirely, replaced by invasive species such as crested wheatgrass, which ranchers prefer as forage. “An industrialized landscape, a monoculture,” Ertz said.

We got out of the car and walked in the June heat into a meadow of dried grass that looked lovely swaying in the breeze. The grass was another invasive weed: cheatgrass, Bromus tectorum, which was imported from Asia in the late 1800s. Its seeds moved on the hooves of cattle and spread so quickly “as to escape recording,” Aldo Leopold wrote in the 1940s. Cheatgrass got its name because it is only edible for a few short weeks before it goes to seed; ranchers considered it a cheat, though they profited, and still do, from its short-term plenty.

Cheatgrass loves land trampled by cows. Like all invasives, the cheat dominates by outcompeting native plants, more efficiently snatching water and nutrients, and more prolifically producing seeds. Unlike native bunchgrasses, which grow among the sagebrush, cheatgrass forms a contiguous mat. It dries up in summer earlier than native grasses, providing opportunities for catastrophic wildfires that burn hotter, faster, and wilder. And in the wake of fire, cheatgrass proliferates. Cheat is the cattleman’s most subtly destructive legacy. The BLM itself has admitted that because of the cheat infestation “a large part of the Great Basin lies on the brink of ecological collapse.”

Eventually, Ertz and I found an isolated upland, north of the Jarbidge, where there had been limited grazing. The air was perfumed with the sharp, cool sweetness of sage, and with blooming silver lupine that smelled like orange blossom and honeysuckle. There were native bunchgrasses in profusion — Idaho fescue, bluebunch wheat, poia. We found bitterroot and bitterbrush, and phlox that flowered blue and pink and white, and the deep-purple flowers of larkspur, a plant hated by cattlemen but beloved by Ertz because it causes asphyxiation in cows and sheep. We saw wild onion and penstemon and mint and rabbitbrush and wild rose and peonies and chokecherries, which flowered in cream-colored, finger-length bunches. Bluebirds perched in the branches of a mountain mahogany, sang, and flew away. For a few minutes, we stood among the snowberry and yarrow and desert dandelions whose seeds floated before our eyes as the breeze took them.