Mr. Earnshaw went to Liverpool and he came back with a boy: a “gipsy brat,” a thing hardly human, an “it” talking “over and over again some gibberish that nobody could understand.” That “dirty, ragged, black-haired child” was christened Heathcliff — a name snatched straight from the wild, coarse landscape around Wuthering Heights. Emily Brontë does not explain Heathcliff’s origins any more than she explains his soul-bond to Mr. Earnshaw’s daughter, Cathy. He just is, like the rocks and trees, like frost or wind or any other weather.

But who might he have been? Caryl Phillips’s tenth novel, THE LOST CHILD (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $26), imagines Heathcliff not as Irish or gipsy but as a half-black bastard born to a starving, twice-sold African slave. His mother spends the voyage from the West Indies chained to the captain’s floor for ease of access. One night, when the ship is docked at an English port, he guiltily turns her loose. Freedom brings new sorrows in the form of a “kind man” who leaves money on the table and leaves her with child.

This story of the “Crazy Woman” is a prelude to Phillips’s central plot, which concerns Monica Johnson, a bookish white woman from the north of England who marries a man from the islands named Julius in the late 1950s. As Julius gets swept into the liberation cause of his unnamed homeland, Monica drifts off with their two sons. She falls into depression and the family into disrepair. The state sends the children to live with a mistrustful white family. One boy is kidnapped and killed by Monica’s pedophilic ex-lover; the other is merely traumatized by neglect. At the center of the book is a chapter narrated by Brontë herself that imagines the feverish drafting of Wuthering Heights, and ends with her, a ghost, attending her own burial.

The Lost Child is a self-conscious rewriting of the colonial past, as much a work of literary criticism as a novel. There is a rhyme scheme at play: three madwomen, one of whom literally winds up in an attic; three abandoned black boys. The pieces fit together only as associations or echoes or argument. Phillips, who was born in St. Kitts and raised in Yorkshire, is not only writing blackness into the Victorian novel; he is drawing attention to the transformation of British society by the postwar immigration of tens of thousands of West Indians and West Africans — which, as he writes in the essay “England, Half English,” has not meant the equal representation of black Britons in literature by white writers.

The novel ends with Mr. Earnshaw dragging his mewling son across the “ghostly blackness” of the “inhospitable moors.” They are headed to Wuthering Heights. “Please don’t hurt me,” the boy thinks as he cries, wanting to return to his mother. The man’s last words are simple, foreboding: “We’re nearly home.” Brontë’s novel is at its base the story of a real estate transfer: a despised fosterling — a captive, really — who becomes a member of the rentier class, the slumlord of a haunted castle. The windows are broken, the best asset is a graveyard — but what a view!

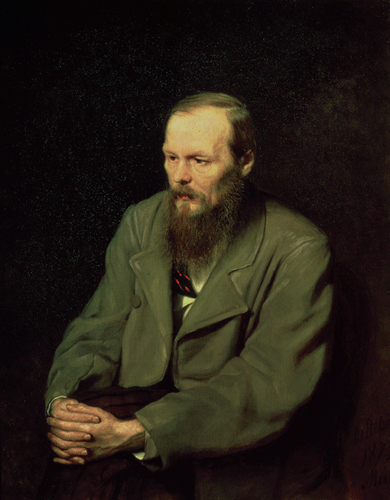

“Every convict feels that he is not at home, but as if on a visit,” Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote in his memoir of his prison years, newly translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky as NOTES FROM A DEAD HOUSE (Knopf, $26.95). “He looks at twenty years as if they were two, and is completely convinced that when he leaves prison at fifty-five he will be as fine a fellow as he is now at thirty-five.” Dostoevsky was twenty-seven years old when he was arrested and charged with political crimes: circulating a letter that was critical of church and state, and being involved in the planning of a secret printing press. His sentence had been commuted from death by firing squad to eight years of hard labor in Siberia when the emperor commuted it once more, to four years of labor and four of military service — but the emperor also wanted to have a little fun. On December 22, 1849, a month after Dostoevsky’s birthday, he and his fellow prisoners were brought to Semyonovsky Square in St. Petersburg. The death sentence was read and the funeral shirts were donned, but the guns were not fired. Prison was the life he was granted after death.

Portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky, by Vasili Grigorevich Perov © Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow/Bridgeman Images

Notes from a Dead House is written in character, by a fictional wife murderer named Alexander Petrovich Goryanchikov, but as Pevear and Volokhonsky note in their excellent foreword, the narrator is rather more like Dostoevsky himself than a man who has committed homicide. The book is largely plotless, a record of institutional habits and routines, though little scenes and colorful dramas emerge. Our narrator is a genius of human observation who takes careful stock of the types he meets — the purple-faced major whose skin is covered in blackheads; the drunks, the fighters, and “resolute men”; the moneylenders; the bowers and scrapers; the ones who brag, unrepentant. Dostoevsky’s constant preoccupation is the meaning of human freedom and the prisoners’ preservation of their dignity, even when suffering 500, 1,500, 4,000 strokes of the lash. The dread of punishment is terrible. To put it off, some men stick a knife into a guard or another convict; their reward is a delay of the inevitable — more lashes, but in one or two months’ time. Some get used to the rod. “Manifold beatings somehow strengthen a man’s spirit and back, and he comes to look upon punishment skeptically, almost as a minor inconvenience, and he no longer fears it.” They lie in the hospital to recuperate between rounds.

“What are we here?” one asks. “We live, but we’re not people; we die, but we’re not dead men.” They are phantoms, passing the days visiting themselves, telling and retelling their tales. But the dead house is also filled with life — with fights and barterings and teasing and drunkenness. The prisoners put on a marvelous Christmas play. They keep geese and a billy goat named Vaska, so fat that “he waddled when he walked.” (When Vaska is discovered by the major and slaughtered, he proves “remarkably tasty.”) Sometimes men run off intending to be caught, desirous only to change their situation — to be sent to a different prison, to gain some variety. Toward the end of the book, two prisoners run off intending to escape for good, and for eight days it seems that they have succeeded. They are celebrated and admired until they are found and returned, when they are mocked, humiliated. The prisoners value what all men do: “Success,” Dostoevsky reflects, “means so much to people . . . ”

Noblemen like Dostoevsky attracted a great deal of attention in the barracks. Some peasants hung on them for the kopeks; others were obsequious to the social order itself. “I could never say no to the various attendants and servants who latched on to me and finally took complete possession of me,” Dostoevsky writes, “so that in reality they were my masters and I their servant.” But he never truly felt part of prison life. This estrangement brought him more suffering than the injustice of his conviction, more than the loss of time or separation from family. The prisoners belonged to the prison and to one another, but the nobleman stood apart.

He is not a friend and not a comrade, and even if over the years he reaches a point where they no longer insult him, still he will never be one of them and will be eternally, painfully conscious of his estrangement and solitude. This estrangement sometimes happens without any malice on the part of the prisoners, but just so, unconsciously. He’s not one of us, that’s all. Nothing is more terrible than to live in a milieu that is not your own.

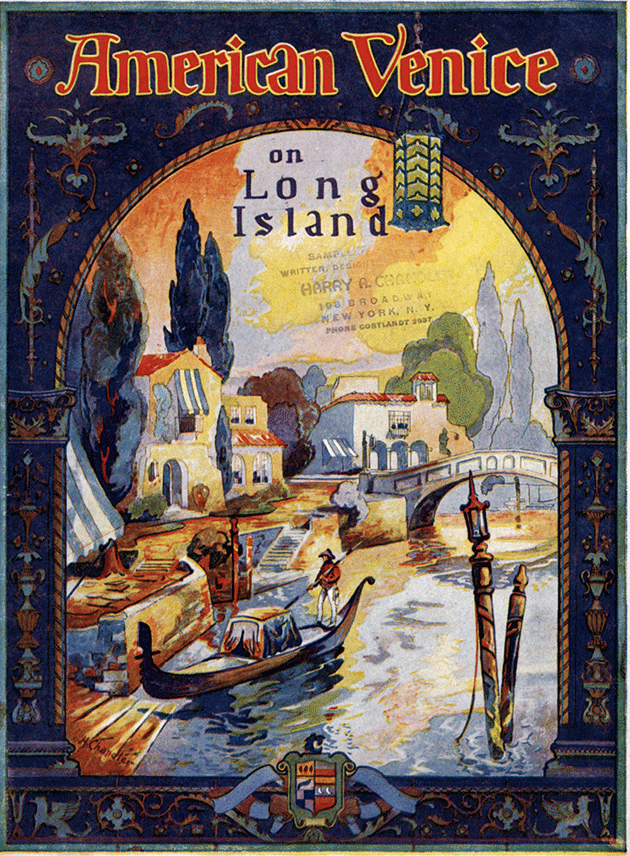

Cover of an American Venice advertising brochure, c. 1925. Courtesy Queens Borough Public Library, Long Island Division/W. W. Norton & Company

Another kind of restricted milieu, designed for a different kind of exile, is the subject of GARDENS OF EDEN: LONG ISLAND’S EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY PLANNED COMMUNITIES (W. W. Norton, $65), a history of real estate development in places such as Bayberry Point, Copiague, Shoreham, and Jamaica Estates, edited by Robert B. McKay. Aided by improvements in transportation, among them the electrification of the Long Island Rail Road, Long Island experienced a building boom that started in 1902 and ended after the financial panic of 1907. Development got back on track a few years later, and Progressive Era builders with visions of how the middle class ought to live, work, commute, and play continued to dredge marshes, dig canals, and reshape the map. Long Island was sold as a utopia free of congestion and crowds, the solution to the city’s expanding population. The advertisements promised paradise on earth — or at least Europe in New York. “A turquoise lagoon under aquamarine sky! Lazy gondolas! Beautiful Italian gardens! Is it Venice on the Adriatic? No — Venice in America!”

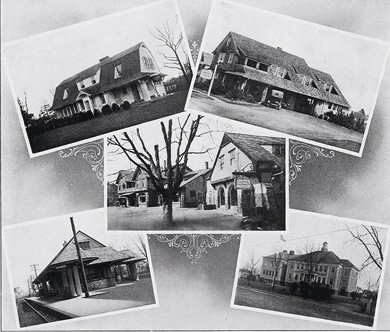

The old photographs in Gardens of Eden offer a tutorial in the Arts and Crafts, Colonial Revival, Tudor Revival, and Mediterranean Revival architectural styles. (Everyone, especially people who had never been there, wanted to live in the English countryside.) The essays at their best are detailed local history; at their dullest they are hagiographies of minor tycoons; at their nadir, brochure copy. A fascinating story of race, politics, and environmental destruction is here, but it’s buried beneath the curvilinear macadam streets.

Page from a Woodman Realty Company brochure, 1911. Courtesy Hewlett-Woodmere Public Library Collection/W. W. Norton & Company

We meet characters like Carl Fisher, a multimillionaire who made his money in the automotive industry and, with his partners, built the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. After Fisher turned Miami Beach from a mangrove swamp into a resort, his attention fixed on Montauk — he outbid Robert Moses, who had wanted the site for a public beach. The combination of a hurricane that ripped up the Florida Coast in 1926 and Fisher’s sundry financial problems meant that Montauk didn’t really take off until the 1950s. Bust does have a way of following boom. Real estate magnate H. Stewart McKnight ran into trouble in 1914 and had to live off the land in Great Neck Estates. According to one essay, McKnight and his wife “would have starved without the produce they raised themselves.” One can’t help but imagine Bruce Ratner, the marquee developer of the current Brooklyn real estate boom, scavenging for nettles in Atlantic Yards.

Turn-of-the-century suburban and resort developers pioneered the practice of covenants that limited commercial development, dictated architectural improvements, and guaranteed minimum construction costs to ensure property values. They also limited who could sign in the first place. These rules could be more or less explicit; Montauk, Old Field South, and other villages had clear whites-only policies. One group of homesteaders who aren’t covered in Gardens of Eden are the African-American residents of Gordon Heights, who came to Long Island in the late 1920s from Harlem, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. Banks would not extend them credit, so a man named Louis Fife financed and sold them hundred-acre square plots. I learned about Fife in a different work of local history, African Americans of Western Long Island, published in 2002 by Jerry Komia Domatob. That book is a slim collection of photographs — of people, not houses — weighted toward firsts: John Thomas, the first African-American police officer in Islip; Janice E. Tinsley-Colbert, the first African-American elected official in Babylon; Curtis T. Skeete, the first African-American medical doctor in Nassau County.

Long Island continues to have some of the most segregated suburban communities in America. In 2013, a federal judge found that the village of Garden City had violated the Fair Housing Act by attempting to block an affordable-housing complex. A 2014 Columbia University report linked housing discrimination to separate and unequal education in Nassau County. Fences keep undesirable elements out; elsewhere, barbed wire keeps them in. Across the United States a network of more than four thousand Siberias holds more than 2 million people — 25 percent of the world’s prisoners. These big houses incarcerate African Americans at six times the rate of whites.