For the past three years my dosimeter had sat silently on a narrow shelf just inside the door of a house in Tokyo, upticking its final digit every twenty-four hours by one or two, the increase never failing — for radiation is the ruthless companion of time. Wherever we are, radiation finds and damages us, at best imperceptibly. During those three years, my American neighbors had lost sight of the accident at Fukushima. In March 2011, a tsunami had killed hundreds, or thousands; yes, they remembered that. Several also recollected the earthquake that caused it, but as for the hydrogen explosion and containment breach at Nuclear Plant No. 1, that must have been fixed by now — for its effluents no longer shone forth from our national news. Meanwhile, my dosimeter increased its figure, one or two digits per day, more or less as it would have in San Francisco — well, a trifle more, actually. And in Tokyo, as in San Francisco, people went about their business, except on Friday nights, when the stretch between the Kasumigaseki and Kokkai-Gijido-mae subway stations — half a dozen blocks of sidewalk, which commenced at an antinuclear tent that had already been on this spot for more than 900 days and ended at the prime minister’s lair — became a dim and feeble carnival of pamphleteers and Fukushima refugees peddling handicrafts.

“Iwaki-shi, Fukushima, 2011,” by Katsumi Omori, from the series Everything Happens for the First Time © The artist. Courtesy MEM, Tokyo

One Friday evening, the refugees’ half of the sidewalk was demarcated by police barriers, and a line of officers slouched at ease in the street, some with yellow bullhorns hanging from their necks. At the very end of the street, where the National Diet glowed white and strange behind other buildings, a policeman set up a microphone, then deployed a small video camera in the direction of the muscular young people in drums against fascists jackets who now, at six-thirty sharp, began chanting: “We don’t need nuclear energy! Stop nuclear power plants! Stop them, stop them, stop them! No restart! No restart!” The police assumed a stiffer stance; the drumming and chanting were almost uncomfortably loud. Commuters hurried past along the open space between the police and the protesters, staring straight ahead, covering their ears. Finally, a fellow in a shabby sweater appeared, and murmured along with the chants as he rounded the corner. He was the only one who seemed to sympathize; few others reacted at all.

But now the drummers were banging away as if for their very lives, swaying like dancers, raising clenched fists, looking endlessly determined. I was astounded to see that listless scattering of the half-seen become a close-packed, disciplined crowd. There must have been 300 or more. They chanted and raised their hand-lettered placards. It was the last night of February 2014. Perhaps after another three years of Fridays they will still be congregating to express their dissent, which after what happened at Plant No. 1 must be considered pure sanity itself. All the same, they were hurried past, overlooked, and left to chant in darkness while my dosimeter accrued another digit. Another uptick, another gray hair — so what? With radiation, as with time, from moment to moment there may indeed be nothing to worry about.

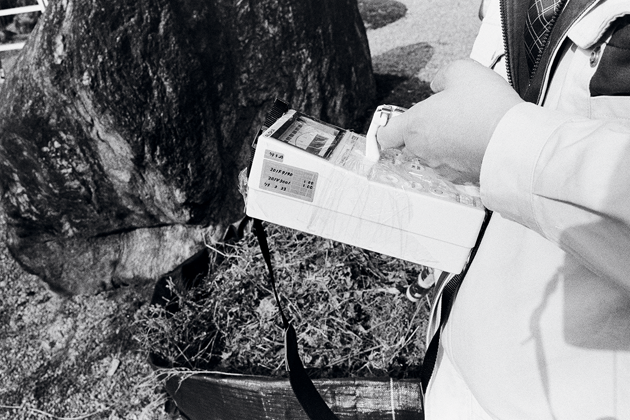

I was happy to see that dosimeter again. By the time I returned to Japan my interpreter had recalibrated it from millirems to millisieverts, the latter her country’s more customary unit of poisonousness. Why not? The thing was hers now; I had given it to her because she had to live here and I didn’t. It was the best I could do for her. To be sure, I had come to deplore its inability to detect anything but gamma rays, since plutonium emits alpha particles, and strontium emits beta particles (which present a danger if strontium is inhaled or swallowed); by July of 2013 these and certain other radioactive substances had been detected in a monitoring well at Plant No. 1. (The concentration of cesium was a hundred times greater than the legal maximum. But why be a pessimist? That well was a good six meters away from the ocean.) At least the dosimeter could keep itself occupied measuring gamma-ray emitters such as cesium-134 and cesium-137, which in that same joyful July kept making news. One Wednesday the Japan Times reported that the isotopes were “both about 90 times the levels found Friday.”

Meanwhile, the JDC Corporation, a construction company, discharged 340 tons of radioactive water into the Iizaka River — but not to worry: it happened, said the Japan Times, “during government-sponsored decontamination work.” (Well, we all make mistakes. You see, the company had not been aware that water from the river would be used for agricultural purposes.) Ten days later, said the same newspaper, the Tokyo Electric Power Company, or TEPCO, which is the nuclear utility that operates the damaged plant, “now admits radioactive water entering the sea at Fukushima No. 1 . . . fueling fears that marine life is being poisoned.” The dangerous hydrogen isotope tritium had already been detected in the ocean back in June, and the amount was climbing. But TEPCO would fix things, no doubt.

A crumbling building in Odaka, inside the original twenty-kilometer exclusion zone surrounding the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, 2011 © Donald Weber/VII

In August 2013, the Japanese Nuclear Regulation Authority, which thus far had treated the leak as a level 1 “anomaly,” recategorized it at level 3, a “serious accident.” Meanwhile, the Japan Times was calling the situation “alarming” and speaking of trillions of becquerels of radioactivity, which is to say, “about 100 times more than what TEPCO had been allowing to enter the sea each year before the crisis.” A year later TEPCO estimated that tritium emitting 20 to 40 trillion becquerels of radiation per liter may have flowed into the Pacific Ocean since May 2011. To prevent No. 1 from exploding again, and maybe melting down, TEPCO cooled the reactor with water and more water, which then went into holding tanks, which, like all human aspirations, eventually leaked.

By September 2013, South Korea had banned the importation of fish from eight Japanese prefectures. And in February 2014, when I began my second visit to the hot zone, the cesium concentration in one sampling well was more than twice as high as the record set the summer before. A day after that was reported, the cesium figure had again more than doubled. As for strontium levels, TEPCO confessed that it had somehow underreported those; they were five and a half times worse than had been previously stated. Three hundred tons of radioactive water were now entering the ocean every day. (A spokesperson for TEPCO says that the situation has since improved: compared with the period before August 2013, levels of strontium-90 have been reduced by about one third, and levels of cesium-137 by one tenth.)

Meanwhile, there were still 150,000 nuclear refugees. Many remained on the hook for the mortgages on their abandoned homes.

Another hilarious little anecdote: Many poor souls had toiled for TEPCO in the hideous environs of No. 1, and some had been exposed to a dose of more than a hundred millisieverts of radiation. A maximum of one millisievert per year for ordinary citizens is the general standard prescribed by the International Commission on Radiological Protection. According to The First Responder’s Guide to Radiation Incidents, first responders should content themselves with fifty millisieverts per incident, for although radiation sickness manifests itself at twenty times that dose, cancer might well show up after lower exposures. But the tale had a happy ending: The workers would be allowed to undergo annual ultrasonic thyroid examinations free of charge.

TEPCO projected the total cost of the disaster at 978 billion yen, or 8.4 billion U.S. dollars.

Nevertheless, as the Japanese government kept advising in the aftermath of the disaster, there was “no immediate danger.” And important plans were being drawn up to save the world. The idea was to build an electric-powered “wall of ice” around Plant No. 1 by inserting over 1,700 pipes ninety-eight feet underground for nearly a mile. Coolant flowing through them at -22 degrees Fahrenheit would then freeze the groundwater in the surrounding soil. Many doubted, however, that it would be possible to maintain the wall in a place where summer temperatures can top 100 degrees. In June 2013, only weeks after construction began, the company met new troubles freezing contaminated water for disposal. “We have yet to form the ice stopper,” it admitted, “because we can’t make the temperature low enough to freeze water.” In July, TEPCO announced that it was adding more pipes. The project would cost only 32 billion yen, and with any luck there wouldn’t be another tsunami in the area until the radioactivity subsided.

How long might that be? Take tritium, which has a half-life of 12.3 years. Only after ten half-lives will radiation levels fall to what some realists consider an approximation of pre-contamination. If the reactors somehow stopped polluting the ocean tomorrow, it would still be well over a century before their tritium became harmless. And tritium is one of the shorter-lived poisons in question.

To be sure, dilution works miracles. And on that bright side, Yamazaki Hisataka, a founder of an NGO called No Nukes Plaza, told me that “the radiation has traveled through the Pacific. As a result, it has reached the waters off of the American West Coast. Unless we stop it now, it’s going to get worse and worse.” When I asked whether the ice wall was practical, he laughed. “No,” he said. “Concrete or some permanent barrier would be better.” Did I mention that Japan’s reactor-studded islands are entering one of their cyclical periods of earthquake activity? This is why TEPCO’s wall of ice resembled the fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty, in which it is possible to wall off time with something permeable only to the brave.

When it comes to Japan, arithmetic is now one of my favorite distractions. One sievert is the equivalent of a thousand chest X-rays. A millisievert, the recommended maximum annual dose, is, of course, a thousandth of a sievert; a microsievert a millionth. American first responders are recommended not to exceed 250 millisieverts when saving human lives, but we know surprisingly little about the perils of extended subacute radiation exposure. The so-called linear hypothesis would have it that the multiple of any given dose is the multiple of the danger. For instance: Radiation sickness may begin to appear after a dose of one sievert, but the situation described by this statistic is a rapidly delivered dose, such as a nearby H-bomb detonation or a brief foray to the reactor at No. 1. Fifty millisieverts a year delivered over twenty years, which works out to the same total dose of one sievert, may or may not cause perceptible harm; no one seems sure.

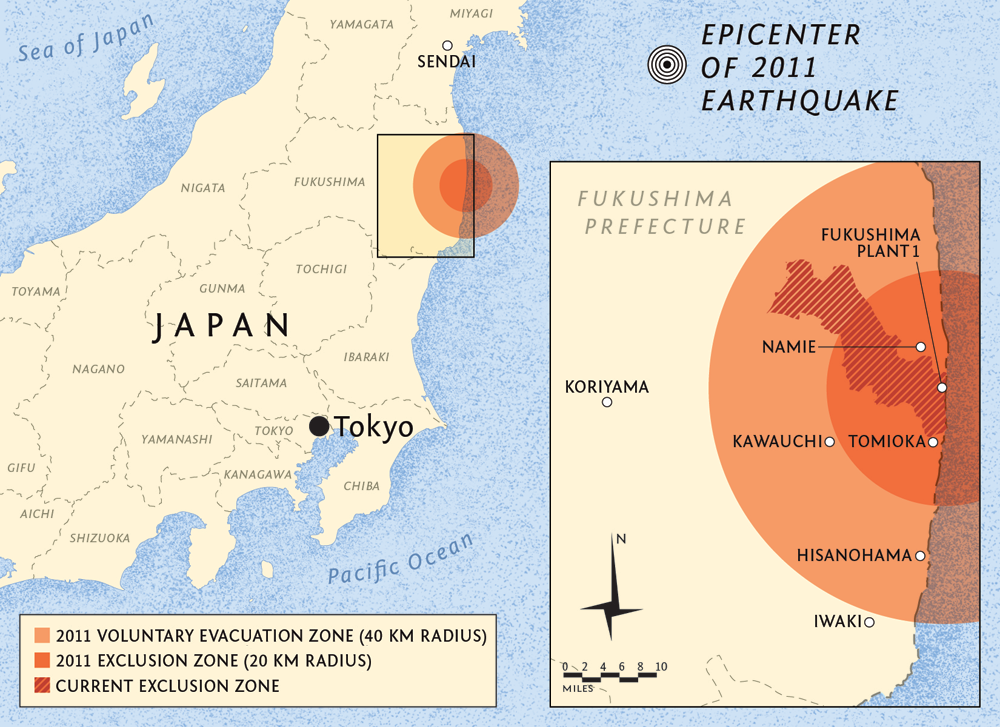

Reactor No. 1 exploded at 3:36 on the afternoon of March 12, 2011, when its exposed fuel rods reacted with the air’s hydrogen. The authorities quickly drew two rings centered on No. 1. The forty-kilometer radius demarcated the voluntary-evacuation zone. The twenty-kilometer radius marked the restricted, or forbidden, zone. As the work of decontamination advanced and wind patterns became better known, the circles were replaced by areas of irregular shape. Once I decided to base my explorations near the forty-kilometer mark, the most convenient place looked like a midsize city called Iwaki. Here the radiation had achieved its maximum at four o’clock on the morning of March 15, 2011: 23.72 microsieverts per hour, or about 600 times Tokyo’s average normal background exposure. Iwaki’s municipal authorities distributed iodine tablets to residents under forty years old and to pregnant women. For the others, as always, there was “no immediate danger.” During my stay in Iwaki, three years later, the dosimeter almost invariably registered its daily microsievert, which is to say, about 0.042 microsieverts each hour. Reader, what might this mean to you? Later that year, when I could afford to buy a scintillation meter, I measured the following good old American values:

0.12 microsievert/hr: Average San Francisco reading, June 13, 2014

0.18 microsievert/hr: Volume II of 1880 census, Boone-Madison Public Library, West Virginia, June 21, 2014

0.30 microsievert/hr: Marble countertop in my room at the Embassy Suites, Charleston, West Virginia, June 22, 2014

0.48 microsievert/hr: Ten Commandments granite tablet in front of courthouse, Pineville, West Virginia, June 23, 2014

2.46 microsievert/hr: Airborne, 36,000 feet, thirty minutes out of Washington Dulles, June 30, 2014

After disembarking from the train in Iwaki one chilly afternoon, I asked the girl at the tourist-information office which local restaurants she would recommend. She replied that the town had always been proud of its seafood, but that because of the nuclear accident the fish now had to be imported.

“Minami Soma-shi, Fukushima, 2011,” from Everything Happens for the First Time © Katsumi Omori. Courtesy MEM, Tokyo

On one of the maps she gave me, I saw that the international port was a few kilometers south. Several beaches lay east, and Route 6 followed the shoreline north toward the reactors. That was the road I would take for my trips to Tomioka, a town partly within the forbidden zone.

In Iwaki, the hotels were nearly always full. One of them smelled of cigarette smoke and was only for decontamination workers. I asked the receptionist at another why she was so busy. She laughed and said, “TEPCO!” Decontamination was a booming business, all right.

In the Iwaki port, which I had expected to find deserted, a dozen sailors in blue coveralls and white hard hats were unwinding a fishing net, planning to travel two hours southward, where the fish were still considered safe; the smaller boats rocked empty on the water. A patrol-boat captain told me that fishing for personal consumption was not restricted, and that fish were tested for radiation once a week. In the meantime, the fishermen, along with so many others in the city, were surviving on what he called “guaranteed money from TEPCO.”

I motored up the coast in a taxi. It was a lovely morning, and the pastel sea was very still. The tsunami-destroyed homes had been deconstructed into foundations, concrete squares upgrown with grass. What I remembered from my visit in 2011 was the black stinking filthiness of everything that the tidal wave had reached. Surely Iwaki’s affected coastline must have been similarly slimed, but these pits looked merely mellow — historic, like archaeological sites. Soon the taxi reached a gleaming skeleton of half-built apartments for people who had lost their homes in the disaster; later I would see many of the temporary barracks-like buildings, all of them still and raw, where nuclear refugees were housed.

Clockwise from top left: Chikara Nipachi, photographed at age sixty-one, a construction worker helping with the cleanup in Minamisoma; Toki Kamata, seventy-eight, a volunteer worker helping to clear the soil and grass from abandoned residences in Minamisoma; Yasutei Yamada, seventy-two, the founder of the Fukushima Daiichi “Suicide Brigade” Volunteers. Yamada’s organization coordinates retired engineers and other specialists to help in the cleanup of the destroyed nuclear facility; Tsunaka Iga, seventy-six, another volunteer working in Minamisoma. All photographs © 2011 Massimo Mastrorillo and Donald Weber/VII

Eventually I arrived at the Northern Iwaki Rubbish Disposal Center, whose monument is its own big smokestack. That is how I first came to see the disgusting black bags of Fukushima: down a forty-five-degree slope, behind a large wall with a radiation-caution sign, a close-packed crowd of those bags stood five deep and I don’t know how many wide. I strode slowly toward the edge of the grass, where the slope began. That was close enough, I thought. The dosimeter did not turn over a new digit.

“This is debris they burned in Iwaki, not fallout,” my taxi driver told me. “They don’t know where to put it.” Several times during our excursion he said that the bags we saw contained ash from the decontamination of Iwaki. In this he was mistaken; the city did not burn radioactive matter. But in saying that they did not know where to put the debris he uttered a truth. By the time I departed Fukushima I hardly noticed the bags unless many happened to be together. The closer to No. 1 one drew, the more there were.

In spite of the reminders that No. 1 was not far away, Iwaki strove to present itself as safe, and maybe it was, given the innocuous dosimeter readings. Contrary claims were considered to be “harmful rumors.” “Even after one week from the earthquake,” according to an official city report, “harmful rumors on the nuclear problems kept blocking the distribution of goods to Iwaki.” In other words, during that first week some fuel and grocery trucks refrained from making deliveries to the city for fear of contamination. The same document told me that “harmful rumors due to the accidents at nuclear power stations degraded the status of Iwaki local products tremendously. To regain its reputation, Iwaki City has participated in more than fifty events held in Tokyo metropolitan area.” Thanks to such efforts, Iwaki had nearly defeated the harmful rumors. Most people’s fears seemed to have been repressed, interred behind a wall of ice as effective as TEPCO’s. Consider my first taxi driver, who was round-faced and patient, and smiled often, wrinkling up his cheeks. Although his hair was still black, he had entered middle age. I asked what he thought when he heard the radiation warnings after the tsunami.

“Even in Iwaki most people tried to flee, but I didn’t mind. I have an elderly person at home, so I couldn’t leave, anyhow!” When I asked if anyone was to blame for what happened, he told me that it was “just bad luck.” In general, he explained, he felt cheerful and hopeful because the taxi business was now thriving thanks to the nuclear-power situation. “Those who work for TEPCO use taxis. If I were a fisherman I would be suffering a lot, but that’s not the case for me!”

My driver the next day had almost as merry an outlook. He was a bald and active old man who wore a paper mask over his mouth, as do many Japanese when they have colds or wish to protect themselves from germs. I asked him to describe the disaster, and he very practically replied: “In the beginning we were busy. Now that the bus services have recovered, it’s quieter for taxis.” On occasion he had entered the prohibited area with Red Cross passengers.

When I asked about the radiation, he replied: “Since it’s not close to here, it has no reality. If someone around here got cancer, I might feel something, but it’s invisible, so I don’t feel anything.” A third driver, asked the same question, said: “There’s nothing to do but trust them.”

I kept asking people in Iwaki how safe they felt; most of their replies were calm and bland. But it did strike me as funny that no doctor I asked would agree to meet me. And it did disconcert me to read in the newspaper that the Fukushima Prefecture Dental Association would now, with family consent, examine the extracted teeth of children aged five to fifteen, first checking for cesium-137 and then, if that was found, for strontium-90. Of course, a test is not a result. Maybe there would be no cesium in anybody’s teeth.

One young man, a recent graduate of the local university, told me that when it came to eating local food, he didn’t “think twice” about it.

“When you go to a sushi restaurant, do you wonder where the fish came from?” I asked.

“I eat what is in front of me,” he replied.

Then there was Kuwahara Akiyo, a weary-looking woman with blue eye shadow and tiny sparkly earrings. She was a part-time employee of the Tomioka Life Recovery Support Center. She told me that she was only allowed to return to her home in Tomioka once a month. Of Tomioka, which I would visit several times, she told me: “There are animals: mice and rats. Also, the pigs interbred with wild boar. The authorities are trying to kill them because they damage the houses, and poop inside and bite the pillars. They don’t know humans, so they are fearless. Sometimes you can see them on the street. And there are so many rats! Wherever we go there, they give us some chemicals to kill the rats.”

Officials from the Japan Atomic Energy Agency and journalists at a decontamination site in Odaka, inside the original twenty-kilometer exclusion zone, January 2012 © Jean Gaumy/Magnum Photos

I asked Kuwahara what she thought about when she envisioned radiation.

“Invisible,” she said, smiling, “and that is the cause of the anxiety. You don’t feel any pain or itching; it just comes into your body.”

“Natural radiation also exists,” she explained, “and if it is natural, it must be all right. I think it’s safe to live in Iwaki. There are nuclear plants all over the world. You can’t flee anywhere.”

“What is your feeling about nuclear power?” I asked.

“My husband’s work is related to nuclear plants. Until the accident we were told that it was totally safe. Nuclear plants we cannot live without.” Then she said: “This was a man-made thing, but we made something so evil, so fearful, so dangerous.”

Hamamatsu Koichi, an Iwaki farmer with cropped gray hair, told me that on the urban farm he ran with his wife, an area of six hundred tsubo, about half an acre, they raised cucumbers, eggplants, broccoli, lettuce, napa cabbage for kimchi, and green onions, whose fresh smell and enticing jade color far excelled anything I had ever seen in an American supermarket. He wore elastic wrist gaiters over the sleeves of his striped shirt, and his eyebrows rose and curved like caterpillars. His industrious wife carefully trimmed and cleaned green onions during the interview, smiling and sometimes even sweetly laughing at my corny radiation jokes. Local produce was still allowed, the couple told me, provided it tested well at the agricultural union. They did not eat the fish. For the first year after the accident, farmers from affected areas were not allowed to sell anything; in the second year, the radiation levels in their vegetables were lower, but they had to lower their prices too: people were afraid to buy the produce. Now the radioactivity had declined. Later, at the train station, I bought a kilogram of Iwaki tomatoes and sent them off to No Nukes Plaza in Tokyo for analysis. They were fine.

I asked Mr. Hamamatsu how he felt about the radiation.

“The TV news said it went even to Shizuoka and damaged their tea,” he told me, “so for sure this place must be contaminated. But we have no place to go.”

“In ten years will you be able to go right up to Plant No. 1 if you wish?”

Folding his hands across his apron, he said, “There may be some spots where you can never return.”

West of Tomioka, at what was formerly the edge of the forbidden zone, lies Kawauchi Village. I had been there shortly after the accident, when houseplants had just begun to wilt in front of the silent homes. In 2013, the Japan Times reported that in Kawauchi the central government’s radiation targets had not been met: even after decontamination, almost half of the 1,061 houses in the “emergency evacuation advisory zone” were still receiving atmospheric radiation doses over one millisievert per year. Suspicious villagers had performed their own gamma-ray surveys. As the newspaper said: “Since the [environmental] ministry hasn’t explicitly promised to do such work again, municipalities are increasingly concerned about the future of the decontamination process.”

A snowed-over tatami store, snow smooth and high across a little bridge over the river, snow heaped on a cemetery’s dark steles — such was the town now. It was almost romantic. It was also almost deserted, except for workers in the streets. I did, however, find the Kawauchi Village Residence to Promote Young People’s Settlement. There was a path shoveled through the snow to the unlocked foyer, though no one was in.

Discarded persimmons whose radioactivity exceeded acceptable levels, Iitate, December 2012 © Yuki Iwanami

Walking farther east on that street, which had been the dividing line between the restricted and voluntary-evacuation zones, I came to a house. Inside, a very small old woman was peering at me through a window. When I rang the bell, she came to the door and pretended to be deaf. Soon a middle-aged man with kind eyes, wearing a dark down jacket, came up behind her. He eventually invited me in.

“That’s my mother,” he said of the woman I’d seen through the window. “My parents live here. They came back in November 2012.” He told me that about half the village was inhabited now, but most of the villagers who had returned only stayed four days a week; on the other days they returned to their temporary housing, in Koriyama or elsewhere. Only about 20 percent lived in Kawauchi full time.

“So your mother feels safe?” I asked.

“Because she is elderly, it’s no use worrying about radiation. Of course she feels lonely; that’s why I am visiting her. The children will never come anymore. The grandchildren won’t come. That is the result of some fear information.”

It turned out that he used to work for TEPCO. “I was not directly involved in the nuclear power plant,” he told me. “My work had to do with the buying and leasing of land for construction. Basically, my personal opinion is that given that original 1960s design, it was risky to choose this location at all. The major problem with the emergency-power generator was that it was installed at sea level, not in the correct place. All the contract workers were saying so, including me.” (TEPCO says that their belief at the time was that this was the safest design.) As emerald-green tea was served by the old mother in her green kerchief and baggy quilted clothes, her son continued, “It’s good to gradually reduce the use of nuclear energy, but now it’s like our blood, our life. All the nuclear plants are currently stopped. You cannot maintain this situation forever.” He spoke of radioactive mushrooms, honey, and wild boar.

When I asked what Kawauchi would look like in the future, he laughed. “Probably it will eventually die out. The families with young children won’t live here.” His family had been in Kawauchi for close to a hundred years. In that small tatami room, with the old lady half-tucked under a blanket, I watched the clouds and dripping snow through the window and thought what a pleasant home it was. I asked the old lady what she most liked about this place. She smiled. Her teeth were a lovely white. She exclaimed: “The air is clean!” Perhaps it was, for during my hour and a half in Kawauchi my dosimeter did not accrue any more digits.

Kida Shoichi, at the time a decontamination specialist in Iwaki’s Nuclear Hazard Countermeasures Division, told me that he considered his city not to be badly off, thanks to the winds; as he explained when we spoke in his office, from the TEPCO plant “the northwest direction is high in radiation, so Iwaki is low.” On his laptop, he showed me Iwaki’s 475 monitoring posts. Then he zoomed in: “Here is the city office where we are right now. And here is the monitoring post. It’s 11:05 a.m., and we’re receiving 0.121 microsieverts per hour.” Clicking on Tomioka he said: “The highest is about three microsieverts per hour, so that’s only 24.8 times more than here.” He cut himself off: “No, here’s a place that measures four. And here’s a five, so that’s forty-one times higher . . . ” He next zoomed in on a monitoring site in Futaba Town, which was still in the prohibited zone: 13.61 microsieverts per hour. If those levels kept up, that unlucky part of Futaba would be 112 times more dangerous than Iwaki.

“Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, 2011,” from Everything Happens for the First Time © Katsumi Omori. Courtesy MEM, Tokyo

I asked when he thought Plant No. 1 might be safe; he estimated that it might be 500 years. The next day, he telephoned me with a correction: In only 300 years, barring further accidents, the radiation will have decayed to a thousandth of its original strength!

When I got home, I asked Edwin Lyman, from the Union of Concerned Scientists, what he thought about 300 years as an estimate. “Well, there’s radioactive decay, plus transfer to soil; it will go deeper and deeper and get into the water and so forth.” He thought that natural decontamination would take hundreds of years at least.

In Japan, the basic guideline for decontamination was to reduce radiation in an area to less than one millisievert per year. Thirty percent of the reduction in cesium isotopes around Iwaki had already happened naturally, and Kida gave me some multicolored information sheets to prove it. In November 2011, almost every part of the area had been yellow, meaning “decontamination required.” By December 2012, the yellow had melted into a crescent along the north and east, along with a few patches in the south.

Wasn’t this good news? Iwaki was becoming safe much more quickly than I would have expected. But I wondered what was happening to that cesium. Did it sink deeper into the earth, as Lyman told me? Did it leach into storm drains and rivers? I had read that it sometimes got concentrated in roots. No doubt the radioactivity of the ground must vary just as the ground itself did, and presumably every square meter of Iwaki would need to be measured. (I did not yet have my scintillation meter, but on my next trip, that toy proved that small areas could vary insanely. In Tomioka, one spot might be two microsieverts an hour, and another might be seven or twelve. Deeper into the red zone, of course, the numbers were much higher.) At any rate, the Iwaki municipal report explained that topsoil in schoolyards was being removed if it emitted more than 0.3 microsieverts per hour — which works out to 2.63 millisieverts per year.

During my visit, Kida promised me an excursion with a scintillation counter, and so the next day his deputy, Kanari Takahiro, came to collect me. This young man might have been a little cynical, since he referred to nuclear-mitigation efforts as “casual countermeasures.” I liked him for that.

In Iwaki, “we have never felt the imminent desperate situation,” he said. “In fact, my parents returned home in only two weeks. I myself couldn’t flee since I am a civil servant.”

“Around here, do people tell any jokes about radiation?” I asked.

“The radiation level is not high enough to create any jokes.”

“Are you sad not to eat the local fish?”

“I don’t care. Whatever fish, anywhere it comes from . . . ”

The scintillation counter (which is to say an Aloka TCS-172B gamma-survey meter) cost about a hundred thousand yen. As the technical name implied, it measured only gamma waves, like my dosimeter. Kanari said that its operation was “not difficult.” The decontamination procedure he described was this: Measure radiation; scrape up surface soil and cut tree branches as needed; place the dirt and wood in a bag.

In Iwaki we met a manager and a construction boss. They wore hard hats, work jackets with white belts, and baggy pants tucked into calf-length rubber boots. When I asked whether it was a union job, they curtly replied that it was not. I told them they were heroes. Reducing radioactivity by half, as they were doing, was better than nothing, and anyhow they were endangering themselves. The work was all paid for by the central government, they told me.

They said the decontamination workers in Iwaki were exposed to about 4.5 microsieverts a day, which works out to 1.64 millisieverts a year, while the poor souls who were trying to ice away No. 1 were getting up to 40 millisieverts a year. The manager and the boss had to think about their own dose; though they both wore dosimeters, they never checked them. “The radiation level is so low here that we are not worried,” one said.

An antinuclear demonstration in Iwaki, sponsored in part by a railway labor union. Photograph by the author

I traveled with them to Hisanohama, about sixteen kilometers north of the Iwaki city center, where a traditional Japanese-style house was being decontaminated. I asked Kanari to test things. In the yard, a bag of waste that a worker was filling emitted 0.3 microsieverts per hour. Another bag registered 0.26.

“What happens to these bags?” I asked.

“We remove them and put them in temporary storage for three years,” the manager answered.

“Temporary storage” turned out to mean, for instance, those fields all around Iwaki with the black bags.

“Then what?” I asked.

He smiled, laughed, shrugged. Then he explained: “Unlike the United States, where there are rules, here we make up the rules.”

I had Kanari test a potted houseplant: 0.14 microsieverts; the construction boss’s boot: 0.11; a dirt berm behind the house: 0.33; a rain channel in the sloping concrete driveway: a surprisingly low 0.16; the drainpipe: 0.49. That last reading was not so good; it meant 4.29 millisieverts per year.

I pointed to the pipe and asked him: “How can you decontaminate it?”

“Structurally speaking, unless you break it, it’s rather difficult. We must see what the property owner says.” The two decontamination men agreed that cesium generally went about five centimeters into the ground. We measured two black bags side by side: 0.35 and 0.38 microsieverts. Across the highway was a field of vegetables. I asked Kanari to read the crops for me, but he said: “The scintillation meter measures only the air, not the thing.” All the same, he did as I requested: 0.13 microsieverts away from the ground, 0.18 close to the ground, near a napa cabbage.

Top: Fresh fish at the Iwaki fish market, 2011. None are from Japan © Dominic Nahr/Magnum Photos. Bottom: An official radiation-measurement station near Iitate, 2012 © Andrea Bonisoli Alquati

We drove to a nearby town called Ohisa. There were some heavy blackish-green tarps decorated by a do not enter sign. The air read 0.17 about two meters from the sign. This was about four times more radioactive than downtown Iwaki. There was a forest, but Kanari was reluctant to measure it, since the municipality’s only concern was to decontaminate places where people actually lived. I finally coaxed him into a snowy bamboo grove behind a field at the edge of a mountain. We all listened to the sounds of that lovely bamboo, which resembled birdsongs or windy hollow gurglings. The forest read 0.43 microsieverts per hour, nearly four times the goal of one millisievert per year. (Kida of course had said that 0.5 microsieverts per hour would be acceptable to him, so he might not have minded this place.) If all went perfectly from here on out, it would take at least sixty years to get the radiation from cesium-137 in the forest to the target level. But the government would do nothing about this, since, as Kanari told me sadly, the forest is “endless.” Besides, he said, “This is not the place where people often go.”

As we came closer to the restricted zone, we began to see black bags; it was disgusting how they went on and on. “Temporary storage,” Kanari remarked. “Once the intermediate disposal site is ready, they’ll move there.”

“Where will that be?” I asked.

“Well, we hope there will be such a place, but none of us wants it near us,” he replied.

We cruised up Highway 6 and came to Tomioka. I had to give Kanari directions. From his expression, it seemed he might have been having second thoughts. At the border of the exclusion zone was a checkpoint where the police stood watch over a double lane of traffic cones. When I asked him to pull over near an abandoned pachinko parlor, he kept the engine running. Was he anxious, or did he simply wish to get back to work?

Right by the pachinko parlor his scintillation counter read 4.2 microsieverts per hour — about ten times the level of that mildly dangerous drainpipe in Hisanohama. At a nearby house with yellow danger tape around it, the base of a drainpipe registered 22.1 microsieverts per hour. The daily dose would be 530.4 microsieverts; the yearly dose, 193.6 millisieverts. A little perilous, I’d say. The grassy field was a cool 7.5 microsieverts per hour — 65.7 millisieverts per year — while the main highway on which the decontamination trucks kept raising dust was only 3.72 per hour, which still comes to thirty-two times the recommended annual dose. After fifteen minutes, my dosimeter had gained its own microsievert, which it normally did only once a day, and Kanari wanted to get out of there. So we sped back, to the place where we eat whatever is put in front of us.

For me, Tomioka, whose pre-accident population had been between 10,000 and 16,000, resembled the Iraqi city of Kirkuk, in that each time I returned to it I felt less safe, because each time I knew more and saw more.

There was plentiful vehicle traffic, to be sure — TEPCO workers, mostly, who queued up at the police checkpoint where the exclusion zone began, or dug with shovels, paused, then dragged picks and rakes across gravel, decontaminating. But the rest was quiet enough. I often tasted metal in my mouth there; I don’t know why. The first time I visited, days before my excursion with Kanari, I walked past closed garages, a shuttered sliding door, forsaken shells of buildings. On one trip, I entered a garment store where some of the forms lay cast down. The rest were still standing, eerie silhouettes of headless, legless, armless women; a vacuum cleaner had fallen over on its side. All around were dead weeds, tall and half-frozen, outspreading lace-tipped finger stalks, projecting complex and lovely shadows on the white walls of silent houses whose curtains were neatly drawn. Grass rose up on the sides of the buildings, and golden weeds bent before crumpled blinds. Behind a fence, metal banged on metal. The banging went on and on like a telegraph.

“Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Shore) 45,” by Lieko Shiga, from her series Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Shore), produced in the Miyagi prefecture before and after the earthquake and tsunami. Shiga’s work will be on view next month as part of In the Wake: Japanese Photographers Respond to 3/11, at the Museum of Fine Arts, in Boston. Photograph © The artist, courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In the city center, the streetlights glowed even in the middle of the day, probably to deter theft, of which there was, apparently, a great deal. Over the whole of Tomioka rang an amplified recorded voice, evidently a young woman’s, but distorted and metallic. She reminded the workers not to spread radioactivity; they should dispose of their protective gear at the screening place on their way home. She said, “If you incinerate something or use incense, be careful not to start a fire,” and she warned the former inhabitants, crackling, “For temporary housing people, make sure to kill the breaker before you leave, and lock the door to prevent thieves.”

The forbidden zone’s current boundary was marked by large, narrow signboards, which said, as rendered in my interpreter’s rather beautiful English:

transportation is now being restricted.

ahead of here is

a “difficult to return zone.”

so road closed.

The signs were flanked by traffic cones, with knee-high metal railings behind, which were low enough that a scofflaw such as I might step over them to enter the forbidden zone. That is what I did, I confess, but only for a moment or two on that occasion.

On that first visit I thought that Tomioka appeared only a little shabby — not really, as my interpreter opined, abandoned; weeds could have done much worse in three years. But after an hour I checked the dosimeter and saw that it had already registered another microsievert. Within a single hour I had received three times as much radiation as I had in the previous twenty-four hours. The dosage in Tomioka, in other words, was potentially seventy-two times greater than in Iwaki.

I cannot tell you all that I wish to about the quiet horror of the place, much less of its sadness, but I ask you to imagine yourself looking at a certain weed-grown wooden residence with unswept snow on the front porch as the interpreter points and says: “This must have been a very nice house. The owner must have been very proud.”

“I’m not worried about any thieves,” Endo Kazuhiro said as we drove to his old house, “since my home is not gorgeous.” This former resident of Tomioka was now the head of a residents’ association in an Iwaki suburb. Both of his parents had been born in Iwaki. About his house, he said: “I wish the thieves would clean it up! I was born there. I’m the fourth generation — more than a hundred years, almost two hundred.”

“When did you last visit?”

“I was there last year, in summer. I only went to visit my ancestors’ tombs.”

In his childhood, he said, the kids played kick the can and hide and seek. “We waded in the river. There were wild boars and foxes — also raccoons, although we didn’t see them so often. Now most of the humans are gone, so the animals might be more rampant.”

“You don’t think they die from radiation?”

“I don’t think so.”

“So they’re stronger in that way than humans?”

He laughed. “I don’t know. There are some abandoned pets . . . ”

“Based on your experience in the field, is decontamination effective?”

“Not at all! It’s the most wasteful, useless activity.”

“Who’s making the money?”

“General contractors from Tokyo City and this prefecture.”

“What do you think about nuclear power nowadays?”

“At this stage, I’m against it, because the response to the accident has been so poor. If the government cares to restart any of these nuclear plants, they’d better do a much better job.”

Endo took me to his house. “But it’s overgrown now,” he warned, “not really presentable.” Over the snow-covered road, the brassy female voice roared about protective gear. He showed me his garden, saying, “The bamboo grew! It’s a forest! Three years ago there wasn’t any.” Within the dankness of his former home, rat droppings speckled shoes, boots, a fan, a vacuum cleaner, shelves, and chairs. Everything had been tipped and tilted by the earthquake into a waist-high jumble. He did not invite me in, and anyhow I saw no point in further trawling through that melancholy disorder, so I took a photograph or two, and then he closed the door.

“When we were told to evacuate, everyone thought we could come back in a few days, so we didn’t take so many things. Residents are allowed to visit for six hours, and only during the daytime.” The Endos had taken their bank book and family portraits. His wife had been back only once. As he put it, “she prefers not to see this.”

Endo was now sixty-two. The accident had occurred when he was sixty. “I wanted to be a subsistence rice farmer in my retirement,” he said. “Right here by the road, this was my field, three hundred tsubo. Elsewhere I had two other rice fields; one of them was near a pond. Well, that was my dream. The house is contaminated with radioactivity. Once the location for the waste site has been established, we will demolish the house. Owners are compensated in proportion to tsunami and earthquake damage. My house is less than half collapsed, so I must take care of the demolition myself. It would have been better if it had collapsed.”

There he stood with his cap tilted upward on his forehead, staring at the wisteria whose creepers aimed at him, bullwhips frozen mid-crack. I wondered whether he felt any impulse to fight them. The amplified woman’s voice roared and echoed. He looked at his house. “Soon the wisteria will crush it,” he said, almost smiling.

One Sunday afternoon in Iwaki, an orator in dark clothes stood, raising his voice, fanning and chopping the air, leaning on the podium, waving, circling, nodding. About 300 people listened to him in the auditorium of the sixth floor of a department-store tower (which also contained the Iwaki city library). There were far more men than women. Few wore suits, for this event had been organized by a national railway union. There was loud applause, and a few listeners raised cameras over their heads to record each speech. One man clambered up a small painter’s ladder for a better angle.

A farmer from near Koriyama was speaking. “There is no place for Fukushima people to throw their anger against,” he said. “We feel the administration has abandoned us. In my dairy farm I cannot feed my cows with my own grass. It is forbidden. The grass, the hay, and the compost are contaminated with cesium. They are just sitting there. Finally the city of Iwaki claimed to clean them but just moved them from one place to another. The cows are having more difficult births.”

A lady in black said, “In the temporary housing where I used to live, in Namie, in two years, out of twenty residents, three died.” Another woman added, “Those who make the decisions are not affected by radiation because they live in Tokyo.”

After the speeches, the protesters went out to the street for a parade. There were whistles, drums, chants, banners of pink and yellow and blue and crimson. Some of the marchers were almost ecstatic as they banged their drums or raised their clenched fists; others shyly or listlessly touched their hands together.

A banner said: stop all nuclear power plants. A banner said: 3-11 antinuclear fukushima action. There was a musical chant about poison rain and children being guinea pigs. I saw hardly any spectators. In a travel agency, a young couple turned and frowned over their shoulders and through the glass. A restaurant proprietor stood unsmiling in his doorway. Three pretty women peered out of a second-story window. Two little girls were walking by; the younger wished to join the protest but the elder was against it.

A man was shouting: “You guys did it, you large corporations and TEPCO! Why should we have to suffer? Solidarity, everyone! Work together!” The sentiment was underscored by furious drumming. The marchers went to an unmarked TEPCO building and delivered demands to a man waiting on the sidewalk. He bowed slightly when he received their document. I felt a little sorry for him. Behind the glass doors, two other men in suits stood watching.

My visit to Tomioka with Endo was the least radioactive of the eight trips I have taken to that place; during our two hours there, the dosimeter registered only one additional microsievert. Over the course of our conversation, he remarked that what he missed most about Tomioka was the shrine at the mountain. I asked whether we could stop by, and he kindly drove me there. The characters on the gate read hayama shrine. Here, the young men of the town had climbed bearing torches during the festival to pray for a good harvest; if you saw the flames at the top of the mountain from your house, the harvest would be fruitful. The festival took place every August 15. Endo had carried the torch every year from age sixteen to forty.

At the shrine, one of the two stone guardian dogs had fallen; not far from his cracked corpse rose the wide stone steps, across which a heavy branch had lately collapsed. Together, we climbed up and looked at the forested hill above the shrine, the place of dead leaves and lovely tall pines. We turned and looked down from the torus at the landscape. Then, finally, we descended to the car and drove away, across that plain of black bags and brown grass, with crows flying up everywhere.

Correction: The legend that accompanies the map of Fukushima misidentified the 2011 exclusion and voluntary evacuation zones. A corrected legend appears above.