I first went to Greenland in 1993 to get above tree line. I’d been hit by lightning and was back on my feet after a long two-year recovery. Feeling claustrophobic, I needed to see horizon lines, and off I went with no real idea of where I was going. A chance meeting with a couple from west Greenland drew me north for a summer and part of the next dark winter. When I returned the following spring, the ice had failed to come in. I had planned to travel up the west coast by dogsled on the route that Knud Rasmussen took during his 1916–18 expedition. I didn’t know then that such a trip was no longer possible, that the ice on which Arctic people and animals had relied for thousands of years would soon be nearly gone.

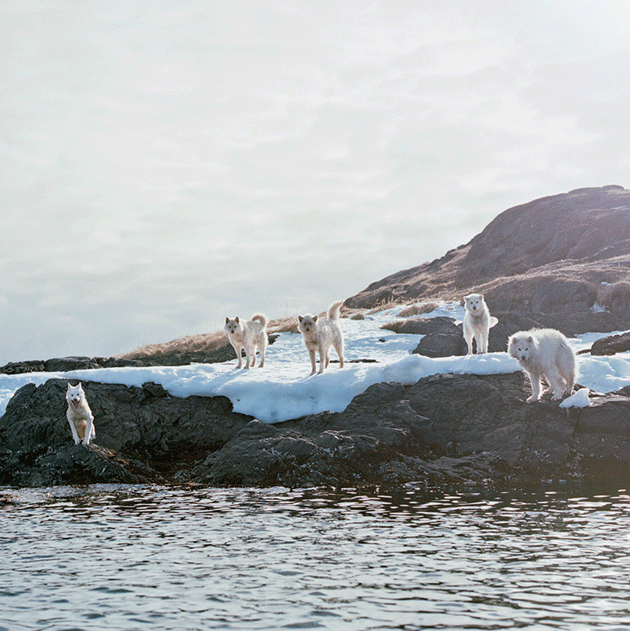

Sled dogs on a small island off the west coast of Greenland, near the village of Aasiaat © Kari Medig

In the following years I went much farther up the coast, to the two oldest northernmost villages in the world: Qaanaaq and Siorapaluk. From there I traveled with an extended family of Inuit subsistence hunters who represent an ice-evolved culture that stretches across the Polar North. Here, snowmobiles are banned for hunting purposes; against all odds, traditional practices are still carried on: hunting seals and walrus from dogsleds in winter, spring, and fall; catching narwhals from kayaks in summer; making and wearing polar-bear pants, fox anoraks, sealskin mittens and boots. In Qaanaaq’s large communal workshop, twenty-first-century tools are used to make Ice Age equipment: harpoons, dogsleds, kayaks. The ways in which these Greenlanders get their food are not much different than they were a thousand years ago, but in recent years Arctic scientists have labeled Greenland’s seasonal sea ice “a rotten ice regime.” Instead of nine months of good ice, there are only two or three. Where the ice in spring was once routinely six to ten feet thick, in 2004 the thickness was only seven inches even when the temperature was –30 degrees Fahrenheit. “It is breaking up from beneath,” one hunter explained, “because of the wind and stormy waters. We never had that before. It was always clear skies, cold weather, calm seas. We see the ice not wanting to come back. If the ice goes it will be a disaster. Without ice we are nothing.”

Icebergs originate from glaciers; ice sheets are distinct from sea ice, but they, too, are affected by the global furnace: 2014 was the hottest year on earth since record-keeping began, in 1880. Greenland’s ice sheet is now shedding ice five times faster than it did in the 1990s, causing ice to flow down canyons and cliffs at alarming speeds. In 2010, the Petermann Glacier, in Greenland’s far north, calved a 100-square-mile “ice island,” and in 2012, the glacier lost a chunk twice the size of Manhattan. Straits and bays between northwest Greenland and Ellesmere Island, part of Canada’s Nunavut territory, are often clogged with rotting, or unstable, ice. In the summer of 2012, almost the whole surface of Greenland’s ice sheet turned to slush.

What happens at the top of the world affects all of us. The Arctic is the earth’s natural air conditioner. Ice and snow radiate 80 percent of the sun’s heat back into space, keeping the middle latitudes temperate. Dark, open oceans and bare land are heat sinks; open water eats ice. Deep regions of the Pacific Ocean have heated fifteen times faster over the past sixty years than during warming periods in the preceding ten thousand, and the effect on both glaciers and sea ice is obvious: as warm seawater pushes far north, seasonal sea ice disintegrates, causing the floating tongues of outlet glaciers to wear thin and snap off.

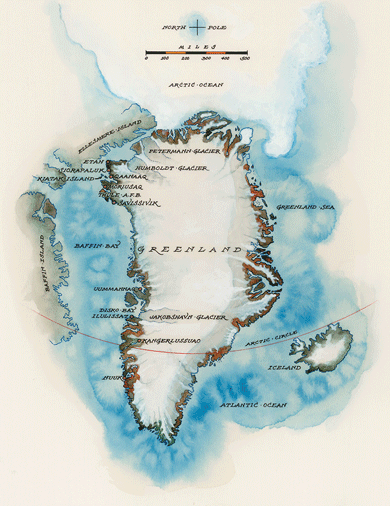

By 2004 the sea ice in north Greenland was too precarious for us to travel any distance north, south, or west from Qaanaaq. Sea ice is a Greenlander’s highway and the platform on which marine mammals — including walrus, ring seals, bearded seals, and polar bears — Arctic foxes, and seabirds travel, rest, breed, and hunt. “Those times we went out to Kiatak and Herbert islands, up Politiken’s Glacier, or way north to Etah and Humboldt Glacier,” the Inuit hunters said, “we cannot go there anymore.” In 2012, the Arctic Ocean’s sea ice shrank to a record minimum. Last year, the rate of ice loss in July averaged 40,000 square miles per day.

The Greenland ice sheet is 1,500 miles long, 680 miles wide, and covers most of the island. The sheet contains roughly 8 percent of the world’s freshwater. GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment), a satellite launched in 2002, is one of the tools used by scientists to understand the accelerated melting of the ice sheet. GRACE monitors monthly changes in the ice sheet’s total mass, and has revealed a drastic decrease. Scientists who study the Arctic’s sensitivity to weather and climate now question its stability. “Global warming has fundamentally altered the background conditions that give rise to all weather,” Kevin Trenberth, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado, says. Alun Hubbard, a Welsh glaciologist, reports: “The melt is going off the scale! The rate of retreat is unprecedented.” To move “glacially” no longer implies slowness, and the “severe, widespread, and irreversible impacts” on people and nature that the most recent report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (I.P.C.C.) warned us about have already come to fruition in Greenland.

It was in Qaanaaq in 1997 that I first experienced climate change from the feet up. I was traveling with Jens Danielsen, headed for Kiatak Island. It was spring, and six inches of snow covered the sea ice. Our fifteen dogs trotted slowly; the only sound was their percussive panting. We had already encountered a series of pressure ridges — steep slabs of ice piled up between two floes — that took us five hours to cross. When we reached a smooth plain of ice again, we thought the worst was over, but the sound of something breaking shocked us: dogs began disappearing into the water. Jens hooked his feet over the front edge of the sled, lay on the trace lines, and pulled the dogs out. Afterward, he stepped down onto a piece of rotten ice, lifted the front of the sled and laid it on a spot that was more stable, then jumped aboard and yelled at the dogs to run fast. When I asked if we were going to die, he smiled and said, “Imaqa.” Maybe.

Ice-adapted people have amazing agility, which allows them to jump from one piece of drift ice to another and to handle half-wild dogs. They understand that life is transience, chance, and change. Because ice is so dynamic, melting in summer and re-forming in September, Greenlanders in the far north understand that nothing is solid, that boundaries are actually passages, that the world is a permeable place. On the ice they act quickly and precisely, flexing mind as well as muscle, always “modest in front of the weather,” as Jens explained. Their material culture represents more than ten thousand years of use: dogsleds, kayaks, skin boats, polar-bear and sealskin pants, bone scrapers, harpoons, bearded seal–skin whips — all designed for beauty, efficiency, and survival in a harsh world where most people would be dead in a day.

From 1997 to 2012 I traveled by dogsled, usually with Jens and his three brothers-in-law: Mamarut Kristiansen, Mikile Kristiansen, and Gedeon Kristiansen. The dogtrot often lulled me to sleep, but rough ice shook me to attention. “You must look carefully,” Jens said. From him I began to understand about being silanigtalersarput: a person who is wise about things and knows the ice, who comes to teach us how to see. The first word I learned in Greenlandic was sila, which means, simultaneously, weather, animal and human consciousness, and the power of nature. The Greenlanders I traveled with do not make the usual distinctions between a human mind and an animal mind. Polar bears are thought to understand human language. In the spring mirages appear, lifting islands into the air and causing the ice to look like open water. Silver threads at the horizon mark the end of the known world and the beginning of the one inhabited by the imagination. Before television, the Internet, and cell phones arrived in Greenland, the coming of the dark time represented a shift: anxiety about the loss of light gave way to a deep, rich period of storytelling.

In Qaanaaq the sun goes down on October 24 and doesn’t rise again until February 17. Once the hood of completely dark days arrives, with only the moon and snow to light the paths between houses, the old legends are told: “The Orphan Who Became a Giant,” “The Orphan Who Drifted Out to Sea.” Now Jens complains that the advent of television in Qaanaaq has reduced storytelling time, though only three channels are available. But out on the ice the old ways thrive. During the spring of 1998, when I traveled with Jens and his wife, Ilaitsuk, along with their five-year-old grandchild, installments of the legends were told to the child each night for two weeks.

That child, now a young man, did not become a subsistence hunter, despite his early training. He had seen too many springs when there was little ice. But no one suspected the ice would disappear completely.

The cycle of thinning and melting is now impossible to stop. The enormous ice sheet that covers 80 percent of the island is increasingly threaded with meltwater rivers in summer, though when I first arrived in Greenland, in 1993, it shone like a jewel. According to Konrad “Koni” Steffen, a climate scientist who has established many camps on top of the Greenland ice sheet, “In 2012, we lost 450 gigatons of ice — that’s five times the amount of ice in the Alps. All the ice on top has pulled apart. It used to be smooth; now it looks like a huge hammer has hit it. The whole surface is fractured.”

In 2004, with a generous grant from the National Geographic Expeditions Council, I returned to Qaanaaq for two month-long journeys — in March and in July. The hunters had said to come in early March, one of the two coldest months in Greenland, because they were sure the ice would be strong then. They needed food for their families and their dogs. We would head south to Savissivik, a hard four-day trip. The last part would take us over the edge of the ice sheet and down a precipitous canyon to the frozen sea in an area they called Walrus El Dorado. It was –20 degrees when we started out with fifty-eight dogs, four hunters — including Jens, Gedeon, Mamarut, and a relative of Jens named Tobias — and my crew of three. We traveled on hikuliaq — ice that has just formed. How could it be only seven inches thick at this temperature? I asked Jens. He told me: “There is no old ice, it’s all new ice and very salty: hard on the dogs’ feet, and, you’ll see, it melts fast. Dangerous to be going out on it.” But there we were.

After making camp we walked single file to the ice edge. The ice was so thin that it rolled under our feet like rubber. One walrus was harpooned. It was cut up and laid on our sleds. I asked about the pile of intestines left behind. “That’s for the foxes, ravens, and polar bears,” Mamarut said. “We always leave food for others.” Little did we know then that we would get only one walrus all month, and that soon we would be hungry and in need of meat for ourselves and the dogs.

“River 2, Position 7, 07/2008, 69°48’08”N, 49°34’14”W, Altitude 922m,” a photograph of the Greenland ice sheet, by Olaf Otto Becker, from his series Above Zero

The cold intensified and at the same time more ice broke up. We traveled all day in frigid temperatures that dropped to what Jens said was –40, and found refuge in a tiny hut. We spent the day rubbing ointment onto our frostbitten faces and fingers, and eating boiled walrus for hours at a time to keep warm. A day later we traveled south to Moriusaq, a village of fifteen, where the walrus hunting had always been good. But the ice there was unstable, too. We were told that farther south, around Savissivik, there was no ice at all. Mamarut’s wife, Tekummeq, the great-granddaughter of the explorer Robert Peary, taught school in the village. She fed us and heated enough water for a bath. Finally we turned around and headed north toward Qaanaaq, four days away. Halfway there, a strong blizzard hit and we were forced to hole up in a hut for three days. We kept our visits outside brief, but after even a few minutes any exposed skin burned: fingers, hands, cheeks, noses, foreheads, and asses. The jokes flowed. The men kept busy fixing dog harnesses and sled runners. Evenings, they told hunting stories — not about who got the biggest animal but who made the most ridiculous mistake — to great laughter.

Days were white, nights were white. On the ice dogs and humans eat the same food. The dogs lined up politely for the chunks of frozen walrus that their owners flung into their mouths. Inside the hut, a haunch of walrus hung from a hook, dripping blood. Our heat was a single Primus burner. Breakfast was walrus-heart soup; lunch was what Aleqa, our translator (who later became the first female prime minister of Greenland), called “swim fin” — a gelatinous walrus flipper. Jens, the natural leader of his family and the whole community, told of the polar bear with the human face, the one who could not be killed, who had asked him to follow, to become a shaman. “I said no. I couldn’t desert my family and the community of hunters. This is the modern world, and there is no place in it for shamans.”

When the temperature moderated, we spent three weeks trying to find ice that was strong enough to hold us. We were running out of food. The walrus meat was gone. Because Greenlandic freight sleds have no brakes, Jens used his legs and knees to slow us as we skidded down a rocky creekbed. At the bottom, we traveled down a narrow fjord. There was a hut and a drying rack: the last hunter to use the shed had left meat behind. The dogs would eat, but we would not — the meat was too old — and we were still a long way from home. The weather improved but it still averaged thirty degrees below zero. “Let’s go out to Kiatak Island,” Jens said. “Maybe we can get a walrus there.” After crossing the strait, we traveled on an ice foot — a belt of ice that clung to the edge of the island. Where it broke off we had to unhook the dogs, push the sleds over a fourteen-foot cliff, and jump down onto rotting discs of ice. Sleds tipped and slid as dogs leaped over moats of open water from one spinning pane to the next. We traveled down the island’s coast to another small hut, happy to have made it safely. From a steep mountain the men searched the frozen ocean for walrus with binoculars, but the few animals they saw were too far out and the path of ice to get to them was completely broken.

A boy from Siorapaluk showed up the next morning with a fine team, beautifully made clothing, a rifle, and a harpoon. At fifteen he had taken a year off from school to see whether he had the prowess to be a great hunter, and he did. But the ice will not be there for him in the future; subsistence hunting will not be possible. “We weren’t born to buy and sell things,” Jens said sadly, “but to live with our families on the ice and hunt for our food.”

Spring weather had come. The temperature had warmed considerably, and the air felt balmy. As we traveled to Siorapaluk, a mirage made Kiatak Island appear to float like an iceberg. Several times, while we stopped the dogs to rest, we stretched out on the sled in our polar-bear pants to bask in the warmth of the sun.

North of Siorapaluk there are no more habitations, but the men of the village go up the coast to hunt polar bears. When Gedeon and his older brother Mamarut ventured north for a few hours to see whether the route was an option for us, all they saw was a great latticed area of pressure ice, polynyas (perennially open water), and no polar bears. They decided against going farther. We had heavy loads, and the dogs had not eaten properly for a week, so after a rest at Siorapaluk we turned for home, traveling close to the coast on shore-fast ice.

On our arrival in Qaanaaq, the wives, children, and friends of the hunters greeted us and helped unload the sleds. The hunters explained that we had no meat. With up to fifteen dogs per hunter, plus children, the sick, and the elderly, there were lots of mouths to feed. Northern Greenland is a food-sharing society with no private ownership of land. In these towns families own only the houses they build and live in, along with their dogs and their equipment. No one hunts alone; survival is a group effort. When things go wrong or the food supply dwindles, no one complains. They still have in their memories tales of hunger and famine. Greenland has its own government but gets subsidies from Denmark. In the old days, before the mid-1900s, an entire village could starve quickly, but now Qaanaaq has a grocery store, and with Danish welfare and help from extended families, no one goes without food.

Back in town after a month on the ice, we experienced “village shock.” Instead of being disappointed about our failed walrus hunt, we celebrated with a bottle of wine and a wild dance at the local community hall, then talked until dawn. Finally my crew and I made our rounds of thanks and farewells and boarded the once-a-week plane south. It was the end of March, and just beginning to get warm. When I returned to Qaanaaq four months later, in July, the dogsleds had been put away, new kayaks were being built, and the edges of paddles were being sharpened to cut through roiling fjord water. I camped with the hunters’ wives and children on steep hillsides and watched for pods of narwhals to swim up the fjord. “Qilaluaq,” we’d yell when we saw a pod, enough time for Gedeon to paddle out and wait. As the narwhals swam by, he’d glide into the middle of them to throw a harpoon. By the end of the month enough meat had been procured for everyone. In August a hint of darkness began to creep in, an hour a day. Going back to Qaanaaq in Jens’s skiff, I was astonished to see the moon for the first time in four months. Jens was eager to retrieve his dogs from the island where they ran loose all summer and to get out on the ice again, but because of the changing climate, the long months of darkness and twilight no longer marked the beginnings and endings of the traditional hunting season.

The year 2007 saw the warmest winter worldwide on record. I’d called the hunters in Qaanaaq that December to ask when I should come. It had been two years since I’d been there, and Jens was excited about going hunting together as we had when we first met. He said, “Come early in February when it’s very cold, and maybe the ice will be strong.” The day I arrived in Greenland I was shocked to find that it was warmer at the airport in Kangerlussuaq than in Boston. The ground crew was in shirtsleeves. I thought it was a joke. No such luck. Global air and sea temperatures were on the rise. The A.O., the Arctic Oscillation, an index of high- and low-pressure zones, had recently switched out of its positive phase — when frigid air is confined to the Arctic in winter — and into its negative phase — when the Arctic stays warm and the cold air filters down into lower latitudes.

Flying north the next day to Qaanaaq, I looked down in disbelief: from Uummannaq, a village where I had spent my first years in Greenland, up to Savissivik, where we had tried to go walrus hunting, there was only open water threaded with long strings of rotting ice. As global temperatures increase, multiyear ice — ice that does not melt even in summer, once abundant in the high Arctic — is now disappearing. Finally, north of Thule Air Base and Cape York, ice had begun to form. To see white, and not the black ink of open water, was a relief. But that relief was short-lived. Greenland had entered what American glaciologist Jason Box calls “New Climate Land.”

Jens, Mamarut, Mikile, and Gedeon came to the guesthouse when I arrived, but there was none of the usual merriment that precedes a long trip on the ice. Jens explained that only the shore-fast ice was strong enough for a dogsled, that hunting had been impossible all winter. Despondent, he left. I heard rifle shots. What was that? I asked. “Some of the hunters are shooting their dogs because they have nothing to feed them,” I was told. A fifty-pound bag of dog food from Denmark cost more than the equivalent of fifty U.S. dollars; one bag lasts two days for ten dogs.

Gedeon and Mikile offered to take me north to Siorapaluk. What was normally an easy six-hour trip took twelve hours, with complicated pushes up and over an edge of the ice sheet. On the way, Gedeon recounted a narrow escape. He had gone out hunting against the better judgment of his older brother. His dogsled drifted out onto an ice floe that was rapidly disintegrating. He called for help. The message was sent to Thule Air Base, and a helicopter came quickly. Gedeon and the dogs (unhooked from the sled) were hauled up into the hovering aircraft. When he looked down, his dogsled and the ice on which he had been standing had disappeared.

We arrived at Siorapaluk late in the day, and the village was strangely quiet. It had once been a busy hub, with dogsleds coming and going, and polar-bear skins stretched out to dry in front of every house. There was a school, a chapel, a small store with a pay phone (from which you could call other Greenland towns), and a post office. Mail was picked up and delivered by helicopter; in earlier times, delivery of a letter sent by dogsled could take a year. Siorapaluk once was famous for its strong hunters who went north along the coast for walrus and polar bears. By 2007 everything had changed. There were almost no dog teams staked out on the ice, and quotas were being imposed on the harvest of polar bears and narwhals.

At the end of the first week I called a meeting of hunters so that I could ask them how climate change was affecting their lives. Otto Simigaq, one of the best Siorapaluk hunters, was eager to talk: “Seven years ago we could travel on safe ice all winter and hunt animals. We didn’t worry about food then. Now it’s different. There has been no ice for seven months. We always went to the ice edge in spring west of Kiatak Island, but the ice doesn’t go out that far now. The walrus are still there, but we can’t get to them.” Pauline Simigaq, Otto’s wife, said, “We are not so good in our outlook now. The ice is dangerous. I never used to worry, but now if Otto goes out I wonder if I will ever see him again. Around here it is depression and changing moods. We are becoming like the ice.”

After the meeting I stood and looked out at the ruined ice. Beyond the village was Kiatak, and to the north was Neqe, where I had watched hunters climb straight up rock cliffs to scoop little auks, or dovekies, out of the air with long-handled nets. Farther north was the historic (now abandoned) site of Etah, the village where, in 1917, a half-starved Knud Rasmussen, returning from his difficult attempt to map the uninhabited parts of northern Greenland, came upon the American Crocker Land expedition and the welcoming sound of a gramophone playing Wagner and Argentine tangos. Explorers and visitors came and went. Siorapaluk, Pitoravik, and Etah were regular stops for those going to the North Pole or to Ellesmere Island. Some, most notably Robert Peary, fathered children during their expeditions. The Greenlanders — and those children — stayed, traveling only as far as the ice took them. “We had everything here,” Jens said. “Our entire culture was intact: our language and our way of living. We kept the old ways and took what we wanted of the new.”

It wasn’t until 2012 that I returned to Qaanaaq. I hadn’t really wanted to go: I was afraid of what I would find. I’d heard that suicides and drinking had increased, that despair had become contagious. But a friend, the artist Mariele Neudecker, had asked me to accompany her to Qaanaaq so that she could photograph the ice. On a small plane carrying us north from Ilulissat she asked a question about glaciers, so I yelled out: “Any glaciologists aboard?” Three passengers, Poul Christoffersen, Steven Palmer, and Julian Dowdeswell turned around and nodded. They hailed from Cambridge University’s Scott Polar Research Institute and were on their way to examine the Greenland ice sheet north of Qaanaaq. As we looked down, Steve said, “With airborne radar we can identify the bed beneath several kilometers of ice.” Poul added: “We’re trying to determine the consequences of global warming for the ice.” They talked about the linkages between ocean currents, atmosphere, and climate. Poul continued: “The feedbacks are complicated. Cold ice-sheet meltwater percolates down through the crevasses and flows into the fjords, where it mixes with warm ocean water. This mixing has a strong influence on the glaciers’ flow.”

Later in the year, they would present their new discovery: two subglacial lakes just north of Qaanaaq, half a mile beneath the ice surface. Although common in Antarctica, these deep hidden lakes had eluded glaciologists working in Greenland. Steve reported, “The lakes form an important part of the ice sheet’s plumbing system connecting surface lakes to the ones beneath. Because the way water flows beneath ice sheets strongly affects ice-flow speeds, improved understanding of these lakes will allow us to predict more accurately how the ice sheet will respond to anticipated future warming.”

Steve and Poul talked about four channels of warm seawater at the base of Petermann Glacier that allowed more ice islands to calve, and the 68-mile-wide calving front of the Humboldt Glacier, where Jens and I, plus seven other hunters, had tried to go one spring but were stopped when the dogs fell ill with distemper and died. Even with healthy dogs we wouldn’t be able to go there now. Poul said that the sea ice was broken and dark jets of water were pulsing out from in front of the glacier — a sign that surface and subglacial meltwater was coming from the base of the glacier, exacerbating the melting of the ice fronts and the erosion of the glacier’s face.

The flight from Ilulissat to Qaanaaq takes three hours. Below us, a cracked elbow of ice bent and dropped, and long stretches of open water made sparkling slits cuffed by rising mist. Even from the plane we could see how the climate feedback loop works, how patches of open water gather heat and produce a warm cloud that hangs in place so that no ice can form under it. “Is it too late to rewrite our destiny, to reverse our devolution?” I asked the glaciologists. No one answered. We stared at the rotting ice. It was down there that a modern shaman named Panippaq, who was said to be capable of heaping up mounds of fish at will, had committed suicide as he watched the sea ice decline. Steve reminded me that the global concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere had almost reached 400 parts per million, and that the Arctic had warmed at least five degrees. Julian Dowdeswell, the head of the institute at Cambridge, had let the younger glaciologists do the talking. He said only this: “It’s too late to change anything. All we can do now is deal with the consequences. Global sea level is rising.”

But when Mariele and I arrived in Qaanaaq, we were pleasantly surprised to find that the sea ice was three feet thick. Narwhals, beluga, and walrus swam in the leads of open water at the ice edge. Pairs of eider ducks flew overhead, and little auks arrived by the thousands to nest and fledge in the rock cliffs at Neqe. Spirits rose. I asked Jens whether they’d ever thought of starting a new community farther north. He said they had tried, but as the ice retreated hungry polar bears had come onto the land, as they were doing in Vankarem, Russia, and Kaktovik, Alaska. The bears were very aggressive. “We must live as we always have with what the day brings to us. And today, there is ice,” he said.

Jens had recently been elected mayor of Qaanaaq and had to leave for a conference in Belgium, but Mamarut, Mikile, and Gedeon wanted to hunt. When we went down to the ice where the dogs were staked, I was surprised to see Mikile drunk. Usually mild-mannered and quiet, he lost control of his dogs before he could get them hitched up, and they ran off. With help from another hunter, it took several hours to retrieve them. Perched on Mikile’s extra-long sled was a skiff; Mamarut tipped his kayak sideways and lashed it to his sled. Gedeon carried his kayak, paddles, guns, tents, and food on his sled, plus his new girlfriend, Bertha. The spring snow was wet and the going was slow, but it was wonderful to be on a dogsled again.

I had dozed off when Mamarut whispered, “Hiku hina,” in my ear. The ice edge. Camp was set up. Gedeon sharpened his harpoon, and Bertha melted chunks of ice over a Primus stove for tea. The men carried their kayaks to the water’s edge. Glaucous gulls flew by. The sound of narwhal breathing grew louder. “Qilaluaq!” Gedeon whispered. The pod swam by but no one went after them. It was May, and the sun was circling in a halo above our heads, so we learned to sleep in bright light. It was time to rest. We laid our sleeping bags under a canvas tent, on beds made from two sleds pushed together. The midnight sun tinted the sea green, pink, gray, and pale blue.

Hours later, I saw Gedeon and Mikile kneeling in snow at the edge of the ice, facing the water. They were careful not to make eye contact with passing narwhals: two more pods had come by, but the men didn’t go after them. “They have too many young ones,” Gedeon whispered, before continuing his vigil. Another pod approached and Gedeon climbed into his boat, lithe as a cat. He waited, head down, with a hand steadying the kayak on the ice edge. There was a sound of splashing and breathing, and Gedeon exploded into action, paddling hard into the middle of the pod, his kayak thrown around by turbulent water. He grabbed his harpoon from the deck of the kayak and hurled it. Missed. He turned, smiling, and paddled back to camp. There was ice and there was time — at least for now — and he would try again later.

In the night, a group of Qaanaaq hunters arrived and made camp behind us on the ice. It’s thought to be bad practice to usurp another family’s hunting area. They should have moved on but didn’t. No one said anything. The old courtesies were disintegrating along with the ice. The next morning, a dogfight broke out, and an old man viciously beat one of his dogs with a snow shovel. In twenty years of traveling in Greenland, I’d never seen anyone beat a dog.

Hunting was good the next day, and the brothers were happy to have food to bring home for their families. Though the ice was strong, they knew better than to count on anything. We were all deeply upset about the beating we had witnessed, but there was nothing we could do. In Greenland there are unwritten codes of honor that, together with the old taboos, have kept the society humming. A hunter who goes out only for himself and not for the group will be shunned: if he has trouble on the ice no one will stop to help him. Hunters don’t abuse their dogs, which they rely on for their lives.

To become a subsistence hunter, the most honorable occupation in this society, is no longer an option for young people. “We may be coming to a time when it is summer all year,” Mamarut said as he mended a dog harness. Once the strongest hunter of the family and also the jokester, he was now too banged up to hunt and rarely smiled. He’d broken his ankle going solo across the ice sheet in a desperate attempt to find food — hunting musk oxen instead of walrus — and it took him two weeks to get home to see a doctor. Another week went by before he could fly to Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, for surgery. Now the ankle gives him trouble and his shoulder hurts: one of his rotator cuffs is torn. The previous winter his mother died — she was still making polar-bear pants for her sons, now middle-aged — and a fourth brother committed suicide. “They want us to become fishermen,” Mamarut said. “How can we be something we are not?”

“The Hard Change, North West Greenland, September 2009,” by Camille Seaman, whose monograph Melting Away: A Ten-Year Journey Through Our Endangered Polar Regions was published last December by Princeton Architectural Press. Courtesy the artist and Adamson Gallery, Washington, D.C.

On the last day we camped at the ice edge, the hunters got two walrus, four narwhals, and ten halibut. As the men paddled back to camp, their dogs broke into spontaneous howls of excitement. Mamarut had opted to stay in camp and begin packing. In matters of hunting, his brash younger brother, Gedeon, had taken his place. Eight years earlier I had watched Gedeon teach his son, Rasmus, how to handle dogs, paddle a kayak, and throw a harpoon. Rasmus was seven at the time. Now he goes to school in south Greenland, below the Arctic Circle, and is learning to be an electrician. Mamarut and his wife, Tekummeq, have adopted Jens and Ilaitsuk’s grandchild, but rather than being raised in a community of traditional hunters, the child will grow up on an island nation whose perennially open waters will prove attractive to foreign oil companies.

At camp, Mamarut helped his two brothers haul the dead animals onto the ice. One walrus had waged an urgent fight after being harpooned and had attacked the boat. Unhappy that the animal did not die instantly, Gedeon had pulled out his rifle and fired, ending the struggle that was painful to watch. The meat was butchered in silence and laid under blue tarps on the dogsleds. Breakfast was fresh narwhal-heart soup, rolls with imported Danish honey, and mattak — whale skin, which is rich in vitamin C, essential food in an environment that can grow no fruits or vegetables.

We packed up camp, eager to leave the dog-beater behind. It was the third week of May and the temperature was rising: the ice was beginning to get soft. We departed early so that the three-foot gap in the ice that we had to cross would still be frozen, but as soon as the sun appeared from behind the clouds, it turned so warm that we shed our anoraks and sealskin mittens. “Tonight that whole ice edge where we were camped will break off,” Mamarut said quietly. The tracks of ukaleq (Arctic hare) zigzagged ahead of us, and Mamarut signaled to the dogs to stay close to the coast lest the ice on which we were traveling break away. We camped high on a hill in a small hut near the calving face of Politiken’s Glacier, which in 1997 had provided an easy route to the ice sheet but was now a chaos of rubble. Mamarut laid out the topographic map I had brought to Greenland on my first visit, in 1993, and scrutinized the marks we had made over the years showing the ice’s retreat. Once the ice edge in the spring extended far out into the strait; now it barely reached beyond the shore-fast ice of Qaanaaq. Despite seasonal fluxes, the ice kept thinning. Looking at the map, Mamarut shook his head in dismay. “Ice no good!” he blurted out in English, as if it were the best language for expressing anger. On our way home to Qaanaaq the next day, he got tangled in the trace lines while hooking up the dogs and was dragged for a long way before I could stop them. These were the final days of subsistence hunting on the ice, and I wondered if I would travel with these men ever again.

The news from the Ice Desk is this: the prognosis for the future of Arctic ice, and thus for human life on the planet, is grim. In the summer of 2013 I returned to Greenland, not to Qaanaaq but to the town of Ilulissat in what’s known as west Greenland, the site of the Jakobshavn Glacier, the fastest-calving glacier in the world. I was traveling with my husband, Neal, who was on assignment to produce a radio segment on the accelerated melting of the Greenland ice sheet. In Copenhagen, on our way to Ilulissat, we met with Jason Box, who had moved to Denmark from the prestigious Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center to work in Greenland. It was a sunny Friday afternoon, and we agreed to meet at a canal where young Danes, just getting off work, piled onto their small boats, to relax with a bottle of wine or a few beers. Jason strolled toward us wearing shorts and clogs, carrying a bottle of hard apple cider and three glasses. His casual demeanor belies a gravity and intelligence that becomes evident when he talks. A self-proclaimed climate refugee, and the father of a young child, he said he couldn’t live with himself if he didn’t do everything possible to transmit his understanding of abrupt climate change in the Arctic and its dire consequences.

Jason has spent twenty-four summers atop Greenland’s great dome of ice. “The ice sheet is melting at an accelerated pace,” he told us. “It’s not just surface melt but the deformation of the inner ice. The fabric of the ice sheet is coming apart because of increasing meltwater infiltration. Two to three hundred billion tons of ice are being lost each year. The last time atmospheric CO2 was this high, the sea level was seventy feet higher.”

We flew to Ilulissat the next day. Below the plane, milky-green water squeezed from between the toes of glaciers that had oozed down from the ice sheet. Just before landing, we glided over a crumpled ribbon of ice that was studded with icebergs the size of warehouses: the fjord leading seaward from the calving front of the Jakobshavn Glacier. Ice there is moving away from the central ice sheet so fast — up to 150 feet a day — and calves so often that the adjacent fjord has been designated a World Heritage Site, an ironic celebration of its continuing demise. Ilulissat was booming with tourists who had flocked to town to observe the parade of icebergs drift by as they sipped cocktails and feasted on barbecued musk oxen at the four-star Hotel Arctic; it was also brimming with petroleum engineers who had come in a gold-rush-like flurry to find oil. But the weather had changed: many of the well sites were non-producers, and just below the fancy hotel were the remains of several tumbled houses and a ravine that had been dredged by a flash flood, a rare weather event in a polar desert.

Neal and I hiked up the moraine above town to look down on the ice-choked fjord. We sat on a promontory to watch and listen to the ice pushing into Disko Bay. Nothing seemed to be moving, but at the front of stranded icebergs fast-flowing streams of meltwater spewed out, crisscrossing one another in the channel. Recently several subglacial lakes were discovered to have “blown out,” draining as much as 57,000 gallons per minute and then refilling with surface meltwater, softening the ice around it, so that the entire ice sheet is in a process of decay. From atop another granite cliff we saw an enormous berg, its base smooth but its top all jagged with pointed slabs. Suddenly, two thumping roars, another sharp thud, and an entire white wall slid straight down into the water. Neal turned to me, wide-eyed, and said: “This is the sound of the ice sheet melting.”

Later, we gathered at the Hotel Icefiord with Koni Steffen and a group of Dartmouth glaciology students. Under a warm sun we sat on a large deck and discussed the changes that have occurred in the Arctic in the past five years. Vast methane plumes were discovered boiling up from the Laptev Sea, north of Russia, and methane is punching through thawing sea beds and terrestrial permafrost all across the Arctic. Currents and air temperatures are changing; the jet stream is becoming wavier, allowing weather conditions to persist for long periods of time; and the movements of high- and low-pressure systems have become unpredictable. The new chemical interplay between ocean and atmosphere is now so complex that even Steffen, the elder statesman of glaciology, says that no one fully understands it. We talked about future scenarios of what we began to call, simply, bad weather. Parts of the world will get much hotter, with no rain or snow at all. In western North America, trees will keep dying from insect and fungal invasions, uncovering more land that in turn will soak up more heat. It’s predicted that worldwide demand for water will exceed the supply by 40 percent. Cary Fowler, who helped found the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, predicts that there will be such dire changes in seasonality that food-growing will no longer align with rainfall, and that we are not prepared for worsening droughts. Steffen says, “Water vapor is now the most plentiful and prolific greenhouse gas. It is altering the jet stream. That’s the truth, and it shocks all the environmentalists!”

In a conversation with the biologist E. O. Wilson on a morning in Aspen so beautiful that it was difficult to imagine that anything on the planet could go wrong, he advised me to stop being gloomy. “It’s our chance to practice altruism,” he said. I looked at him skeptically. He continued: “We have to wear suits of armor like World War II soldiers and just keep going. We have to get used to the changes in the landscape, to step over the dead bodies, so to speak, and discipline our behavior instead of getting stuck in tribal and religious restrictions. We have to work altruistically and cooperatively, and make a new world.”

Is it possible we haven’t fully comprehended that we are in danger? We may die off as a species from mere carelessness. That night in Ilulissat, on the patio of the Hotel Icefiord, I asked one of the graduate students about her future. She said: “I won’t have children; I will move north.” We were still sitting outside when the night air turned so cold that we had to bundle up in parkas and mittens to continue talking. “A small change can have a great effect,” Steffen said. He was referring to how carelessly we underestimate the profound sensitivity of the planet’s membrane, its skin of ice. The Arctic has been warming more than twice as fast as anywhere else in the world, and that evening, the reality of what was happening to his beloved Greenland seemed to make Steffen go quiet. On July 30, 2013, the highest temperature ever recorded in Greenland — almost 80 degrees Fahrenheit — occurred in Maniitsoq, on the west coast, and an astonishing heat wave in the Russian Arctic registered 90 degrees. And that was 2013, when there was said to be a “pause” in global heating.

Recently, methane plumes were discovered at 570 places along the East Coast of the United States, from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to Massachusetts. Siberian tundra holes were spotted by nomadic reindeer herders on the Yamal Peninsula, and ash from wildfires in the American and Canadian West fluttered down, turning the southern end of the Greenland ice sheet almost black.

The summer after Neal and I met with Koni Steffen in Ilulissat, Jason Box moved his camp farther north, where he continued his attempts to unveil the subtle interactions between atmosphere and earth, water, and ice, and the ways algae and industrial and wildfire soot affect the reflectivity of the Greenland ice sheet: the darker the ice, the more heat it absorbs. As part of his recent Dark Snow Project, he used small drones to fly over the darkening snow and ice. By the end of August 2014, Jason’s reports had grown increasingly urgent. “We are on a trajectory to awaken a runaway climate heating that will ravage global agricultural systems, leading to mass famine and conflict,” he wrote. “Sea-level rise will be a small problem by comparison. We simply must lower atmospheric carbon emissions.” A later message was frantic: “If even a small fraction of Arctic seafloor methane is released to the atmosphere, we’re fucked.” From an I.P.C.C. meeting in Copenhagen last year, he wrote: “We have very limited time to avert climate impacts that will ravage us irreversibly.”

The Arctic is shouldering the wounds of the world, wounds that aren’t healing. Long ago we exceeded the carrying capacity of the planet, with its 7 billion humans all longing for some semblance of First World comforts. The burgeoning population is incompatible with the natural economy of biological and ecological systems. We have found that our climate models have been too conservative, that the published results of science-by-committee are unable to keep up with the startling responsiveness of Earth to our every footstep. We have to stop pretending that there is a way back to the lush, comfortable, interglacial paradise we left behind so hurriedly in the twentieth century. There are no rules for living on this planet, only consequences. What is needed is an open exchange in which sentience shapes the eye and mind and results in ever-deepening empathy. Beauty and blood and what Ralph Waldo Emerson called “strange sympathies” with otherness would circulate freely in us, and the songs of the bearded seal’s ululating mating call, the crack and groan of ancient ice, the Arctic tern’s cry, and the robin’s evensong would inhabit our vocal cords.