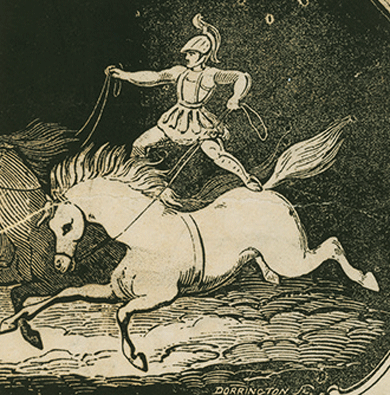

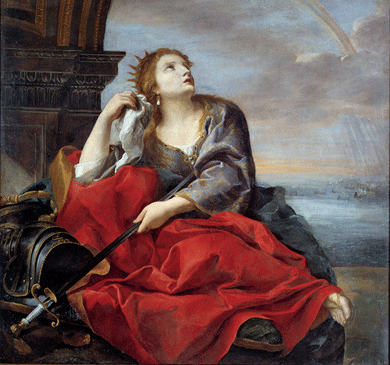

The night before Aeneas set sail from Carthage, Dido, riven with despair, love, and rage, lay awake, set on her own death. Not so the Trojan. He slept easily aboard his ship until Mercury came to him in a dream, chastising him for resting while his betrayed lover plotted gods know what. “Come now, break off your delays,” Mercury urged. “Woman was always a shifting, changeable thing.” Thus persuaded, Aeneas departed, and in the early light the queen fell on her sword. It was a gruesome death, but it had a scenic ending. To free Dido’s soul from her body, Juno sent the messenger Iris, who appeared “trailing a thousand variegated colors shifting against the sun” — a rainbow.

Dido, Queen of Carthage, Abandoned by Aeneas, 1635, by Andrea Sacchi © Scala/White Images/Art Resource, New York City

In Variety: The Life of a Roman Concept (The University of Chicago Press, $55), William Fitzgerald, a professor of Latin at King’s College London, explains that Virgil used the same word, varius, to describe both fickle woman and abundant nature. Its original meaning was visual, and early recorded usages refer to the mottled color of ripening grapes; this unpatterned pattern, however, was readily applied to other surfaces. Fitzgerald offers the memorable example of Plautus’ Epidicus, in which the titular slave is asked how things go with him. His answer — “varie” — puns on the condition of his back, which has been discolored by whipping, and his fortunes, which rise and fall over the course of the play. Such was comedy, to the Romans.

Varietas, which came from varius, describes internal inconsistency — something at odds with itself — as well as to combinations of miscellaneous elements, such as the moretum, a sludgy peasant breakfast mixed in a pot. (Fitzgerald argues that our contemporary notion of the “melting pot” as a metaphor for assimilation should be revised to take into account what actually happened when the Romans combined herbs and cheese; rather than blending together, the ingredients retained their original characteristics, yielding a varius color.) For some, nature’s overwhelming and plentiful variety was a wonder to be praised, a manifestation of God’s will and artistry that exceeded human reason. Variety could even justify the apparent imperfections of the world: Thomas Aquinas wrote that “a universe containing angels and other things is better than one containing angels only.” Creation’s bounty was a sign of God’s providence, which accommodated the human propensity to boredom — though this inclination was itself a weakness, a cause of restlessness and unhappiness.

Still, variety had compensatory value. Pliny the Younger contented himself with dabbling in many fields because he was not good enough, or so he claimed, to excel in any one. “Epicurus thinks that the highest pleasure is limited to the removal of all pain,” Cicero wrote, “so that pleasure can be varied and distinguished, but it cannot be increased.” Antony found “infinite variety” in Cleopatra; others flitted around. But the poems that Ovid wrote enumerating the many kinds of women he found desirable should not be read as a litany of diverse female charms, or antiquity’s “California Girls.” They were meant instead to show off his prowess as a lover, which was so rapacious as to find satisfaction in all women — shy ones, bold ones, nitpickers. (“There is one woman who finds fault with me as a poet, I want to lift up her leg while she criticizes me.”) In love as in rhetoric, varietas delectat only insofar as it wards off satietas. Mere variation becomes inelegant frippery, and infinity curdles to nausea. A satirist is one who is sated.

Coloured Rhythm: Study for the Film, 1913, by Léopold Survage © The Museum of Modern Art, New York City/Scala/Art Resource, New York City

Unlike the tidy totalities of Greek tragedy, varietas is an aesthetic of disunion in action as well as feeling; Cicero celebrated the “varieties of circumstance,” with their power to provoke “surprise and suspense, joy and distress, hope and fear.” For a reader, variety can be a spectacle that overpowers with a deluge of sensuous detail, or an opportunity for, in Fitzgerald’s words, the “sovereign exercise of choice, as the perceiving subject surveys the available profusion, picking and choosing at will.” The critic, confronted with such sublime disarray, usually tries to tie things together — but what if the pieces were left as they are, this and that, one thing after another?

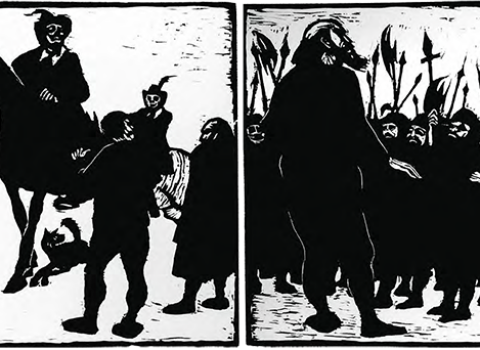

In that spirit of unamalgamated distinctio, consider this final tidbit from Variety, which has no greater meaning than any other, except that I hate to see it left out of the moretum: the evolution of the word desultory. First used to describe “a circus rider leaping from horse to horse,” “desultory” became a way of describing “inconsistent people who change lovers or political allegiance.” Soon after William Cowper deployed it in his 1785 poem “The Task” — which begins with the assertion, more ambivalent than usually acknowledged, that “variety’s the very spice of life” — the word was being used to describe “the random, purposeless activity of the bored,” and was associated with the reading of novels. Now it is found, if it is found at all, only in novels. I don’t know that I have ever heard anyone say it out loud.

Leaping from one horse to the next, we find that both are Trojan breeds. Chino, the thirteen-year-old narrator of Nicola Gardini’s brisk and erudite new novel Lost Words (New Directions, $15.95), is in the midst of translating the Aeneid when his neighbor Ippolito drops in for a visit. Inspired by the open book, Ippolito bursts into an unaided recitation of the opening scene, in which Juno stirs up a storm to deter Aeneas and his fleet. (Gardini, who in addition to being a novelist and a poet is a professor at Oxford, did his graduate work on Renaissance imitations of classical lyric poetry.)

Ippolito declared that the most beautiful hexameter in all Latin poetry was in that passage: Apparent rari nantes in gurgite vasto — Scattered men appear, swimming in the vast swell. . . . Magnificent! But if you thought about it carefully, that scene was hardly possible. Who could have seen them, those poor floundering men? . . . Had I thought about it? Well, they appeared to the gods, that’s whom they appeared to! Whom else? The gods were the witnesses — they were watching!

Detail from a Roman mosaic, second century a.d. © akg-images/De Agostini Picture Library/G. Dagli Orti

They’re not the only ones. Chino’s mother, Elvira, interrupts to give Ippolito some bad news: the signoras in the building don’t like him. He’s intellectual and arrogant, keeps to himself, doesn’t have a wife. (They might also find fault with his taste, which is, by some accounts, a bit prim. “I am one individual who is going to be honest about Vergil and his fucking rari nantes in gurgite vasto,” Henry Miller once complained. “Recess in the toilet was worth a thousand Vergils, always was and always will be.”)

Elvira knows the gossip because she’s also a watcher, and a listener — the doorwoman (she prefers “custodian”) of an apartment building in a poor area outside Milan. It’s 1972, an uneasy time. Fascisti bloody a boy who lives upstairs and an old woman breaks into lamentations for Il Duce; a strike is called at the auto factory where Chino’s father works. But the action almost never leaves the building, a closed, cold place of conformity and pretension. When the landlord sells, giving the tenants the option to buy their apartments, Elvira schemes against her husband’s wishes to purchase a unit. The price is higher than the family can afford, but she never considers looking elsewhere. As Chino puts it, “Only here could her claim to freedom become a form of revenge.”

How did this son of a doorwoman end up a scholar? It was the doing of the mysterious, depressed Mrs. Lynd, Ippolito’s half-English mother, who lived upstairs before he took over the apartment. She was the one who insisted on the importance of a classical education; Chino’s parents, self-confessed proletarians, wanted to send him to a technical school. But Mrs. Lynd — the Maestra, Elvira calls her — was persuasive:

She replied that the word proletarian was as old as the law of the twelve tables, the most ancient Roman legislation, and she launched into a praise of etymology and dead languages that left my parents tongue-tied.

The Maestra also advocates for living languages. She spellbinds Chino with stories of the English dictionary, long since lost, that she compiled while living in India. “A woman who collects and defines words!” she brags. “Unprecedented! Yet a legend tells us that it was a woman who invented the Latin alphabet: Carmenta, the mother of Turnus, Aeneas’ enemy.” As a child, she expected the knowledge of words to illuminate the world, but that was before she discovered that

a word is a meaning that comes into contact with people and assumes a variety of appearances. Everyone sees a little of themselves in it, everyone understands what they can or what they want to understand. Bello, ma. . . ! A mother can be the mother of many children, even if each of them will say that she’s his or her mother.

The Maestra changes Chino. She calls him by a new name — his given name, Luca, which sounds like “luck” — and pulls him away from his family, away from Catholicism, and into the notebook where he copies out thousands of English words. What do you call it when you read a novel in translation that is all about the problems of reading in translation? Ironic? Perverse? Necessary? Whatever the answer, Michael F. Moore’s English rendering is lucid and elegant, a quiet rebuke to the Maestra’s belief that relying on linguistic intercession heralds civilizational decline.

Jhumpa Lahiri also had a notebook, though hers was filled with Italian. She began it in the fall of 2012, during a sojourn in Rome, the city that Aeneas founded. In the front of the notebook she wrote definitions, phrases, and rules of grammar. In the back she kept “a sort of diary” about learning the language. Eventually, after much revision, the back-page notes became essays in the magazine Internazionale; now they are the chapters of In Other Words (Knopf, $26.95), a bilingual memoir that places Italian and English on opposite pages. Ann Goldstein did the translation, because Lahiri didn’t want to. While in Rome she translated a paper she wrote for a literary conference, and hated it. After struggling so hard to express herself in Italian, converting herself back into English felt like “almost a suicide.”

Fans of Lahiri’s short stories and novels probably know that she grew up speaking Bengali at home and English, which she describes as a “stepmother,” at school; Italian is a language she chose. She began studying it in 1994, after a trip to Florence. It takes courage and willed naïveté for a writer as successful as Lahiri to publish in an acquired language. “By writing in Italian, I think I am escaping both my failures with regard to English and my success,” she reflects. It’s her way of becoming another writer — one with the freedom and latitude that goes with being unskilled and unknown, if only to herself. “If it were possible to bridge the distance between me and Italian,” she writes, “I would stop writing in that language.” All the same, she is rueful about her mistakes, and a little embarrassed by her odd, adaptive vocabulary. “One could say that my writing in Italian is a type of unsalted bread,” she writes, in what is, her protestations notwithstanding, a pleasing style. “It works but the usual flavor is missing.”

No one would deny that a native speaker has capacities and instincts that the learner clumsily flails at, and Lahiri does a lovely job of documenting the effort it takes to get hold of these — or fail to do so. And yet, as she is surely aware, for a writer it is impossible to be truly at home in language. As soon as you stop to consider how to say, you have ceased to be natural; you have become, if not foreign, then a little estranged. Writing always arrives late, runs after, falls behind, loses touch, rearranges what was just put in place. It reveals the restlessness of language itself, in all its shifting, multicolored variety.