The old woman’s husband, even older than she, has lived long enough. She is careful not to say this to her daughters, to her brother, to the doctors. He’s had a stroke, or something like a stroke, and at first he seemed to be recovering. Then there were intermittent bad days and setbacks and now, a few weeks in, they are all bad days: he is declining, delirious, difficult, and she is exhausted. Her mind — usually a badger den of plans, desires, and, most of all, worry — now, at night, in its rare moments of rest, tumbles into a pale white silence. She doesn’t want him to live on like this, biting the nurses like a dog that needs to be put down.

Yet here he is, just how he’s always been, a model of his essential personality recast in dementia and physical breakdown. She is shocked to see it, really, his bad timing, his ill temper, and the need, the need, the need, the same for decades, all of it still intact and now amplified. Offsetting this in his best years had been his intellect and his posture of strength and authority, false though it might have been. Or was. False though it was. And his energy: he moved about, read a great deal, thought, worked in the yard. These things compensated. He is not an attractive man but his eyes are dark and penetrating and he has until now been physically sound. He took modest care of himself and brought to her life a rough, sometimes satisfying, sometimes intrusive passion.

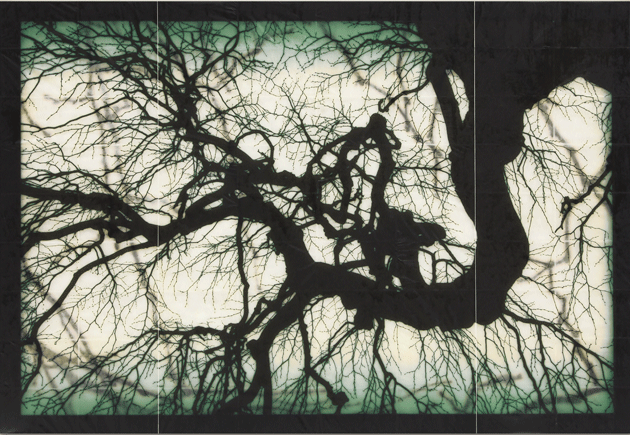

Structure of Thought 30, by Doug and Mike Starn. Courtesy the artists and Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York City

A wall has been constructed across the plain of her memories: that was then, this is now. Now he mutters. Now he is rigid with rage. They sedate him, he won’t sleep. They sedate him again and he quiets, appears perhaps to be asleep (every day this ritual: she asks the nurse, why not just double the dose to start with and the nurse says the doctor has to do that, we can give him more when he doesn’t sleep, but we can’t change the original dose; so the old woman says, why not tell the doctor and the nurse says, honey it’s on the charts and if we told the doctors all the things they should do different we’d be here all day and all night and nobody to take care of the patients either), and with the second load he does sleep but often he is rigid, supremely tense, engaged beneath the skin of sleep in some battle with history, with his life, enouncing some jeremiad against all the forces that had kept him from the life he’d wanted, whatever that is. She had heard all about this on day three, when the one good psychiatrist, a geriatric specialist, gently questioned him about his life, his work, his career. How long have you been married, the psychiatrist said. Too long, he answered. She was sitting right there looking at him. He knew her but could not remember her name. Is this your wife, the psychiatrist said, indicating her. Her? No, no. . . . A pause. Then: She works here. She runs the place.

All wrong all wrong. Everything. All that happened, askew. What’s the matter with these people? Wrong the way it all went. His life is incorrect. How has he ended up here? Someone should tell him what is going on. He has children. He has children, all girls. No wife. He has never married. I’ve never been married, he says. He’s had cats. He liked the cats and he remembers the names, the personalities, of every one of them. Maybe not every single one but most of them. There were Gatsby and Gloria, Duffy and Ev, which stood for Everyman. There was Pox. Pox on all your houses. Even the yard cats who’d rarely come in the house, who’d stayed and left and come back, he knows them all. He can see them all. He is certain he hasn’t forgotten any. Are his children here? There were so many women he’d wanted to have. So many. He’d be hard behind his desk half the day. He’d jerked himself off behind the wheel in the car sometimes, slow-rubbing himself through his pants. Oh he’d been afraid. To do things, to seduce a woman, to control his life. Afraid. He never told anyone anything, never said oh this, oh that. Never said, I was thinking today. . . . Because anything he was thinking today, they shouldn’t know about. Home, after work, he’d push his shorts into the bathroom hamper, he’d shower and change, take care of himself if he hadn’t come off in the car. He remembers stepping into the shower, hard, wanting. Desire is a torment. He wants to touch his cock now but something is wrong with his hands — where are the people who are supposed to tell him what is happening? This one poking at him, what did she want? She is a black, like the rest of them — where are all these blacks coming from? No, no, it wasn’t right. There had been no wife, there had been no wife, he is certain there had been no wife. There has been only himself, his paralysis, and his desire.

It isn’t an aneurysm-type stroke, the doctors call it a “brain bleed.” It could have been happening for a while. The blood is still there in the brain, the wife is told, and she says, oh there must be a lot of pressure then and the older resident, the woman from Pakistan with the very dark hair, says, well, fortunately, there’s a lot of atrophy, too. In other words, she doesn’t need to add, there’s space. Then she gives a little nervous laugh as if she shouldn’t have said such a thing. I’m sorry, she says. I don’t mean fortunately exactly. . . . The old woman nods, understands; she likes this resident, funny name, who speaks plainly and directly and brings the scientist’s remove together with a reassuring emotional engagement. A sense of empathy. One used to say warmth; one no longer says warmth. When the blood drains, he’ll be more stable, the resident says. But it’s possible that there are small events all the time, we have no way of knowing unless there is some dramatic change. For instance, she says, if he falls or if suddenly he cannot use his arm or loses some functionality in walking, holding things, speaking. Then we will know. Funny how she accents the words, ALL dee time, DRAH-mah-tic change, DEN vee vill know: the song of it goes from high to low: the old woman hears it later in her head like music. The doctor says, probably there are small events we don’t notice, that we cannot see.

The old woman says, thank you, you’ve been very good. You’ve been the best doctor of all the ones we’ve seen. You explain things so well and . . . She doesn’t finish but takes the doctor’s hand. A Visitation scene: they touch for a moment, faces communicating good wishes, suffering, gratitude. Two women, one older, the other younger.

After he is seven weeks in the hospital and rehab and nursing facility, the old woman brings him home: he recognizes the place but no one in it. Except the cat. He knows the cat. The cat seems to make him happy. The old woman is afraid to look at the bills. Long phone calls with Medicare. So hard to understand, the labyrinthine punishments of the bureaucracy, the utter lack of recognition of human reality, of human language. She orders an elevator seat for the stairs. Almost ten thousand dollars it costs, installed. Medicare reimburses nothing. Nothing for this essential device.

Oh they want him to recognize every damn thing that he doesn’t recognize and he doesn’t wish to recognize. So-called facts. An endless stream of connections and relations: I’m your daughter, she’s your wife, etc., etc. Don’t you recognize her? They show him a picture. That’s Margaret, your granddaughter!

These are — he mumbles it low, there is in him still some primitive caution — distaff interpretations. He believes nothing these women tell him. This is this and that is that: how do they know? And why should they tell him the truth? They just want to keep him here.

The No Mind Not Thinks No Things vokgret, by Doug and Mike Starn Courtesy the artists and Galerie Lelong, New York City

This place isn’t as nice as the one up the street, he says.

Oh no? the old woman says. What place up the street is that?

Up the street, he says. He can’t remember which way but he can see it. In his mind. He knows it’s there.

Well I’m awfully sorry, the old one says and takes his plate. He watches her. She goes into the kitchen. He senses something lightweight, imbalanced: off. Are the children in the kitchen?

Where are the children? he calls out to her.

They grew up, she says.

How do you know? he says.

They told me, she calls.

Of course. Of course they grew up. There is no other place up the street. Once in a while it all comes flooding in on him, the reality of his situation: a stream of blessed sunlight that in a bare moment turns utterly, painfully blinding. He has to close his eyes. He can’t breathe. He gasps and gasps again. They say, what’s the matter what’s the matter what’s the matter? He looks at them. He knows these people! Who are they?

I feel as if I’ve been unplugged from the universe, he says. He sits. Then he wants to get up. He tries to get up. Up, up, up! He needs to go! Wait, they tell him, wait. The walker your walker you need your walker! Dad? You need your walker.

Who are you, he says. She’s younger and better looking than the other one. He likes to watch her in the cowboy pants. And her boots.

I’m your daughter, she says.

You work for the rodeo, he says. He looks at her: I have a daughter?

Several, she says.

That’s too bad, he says. She looks at him as if he’s a cow in the Lord & Taylor parking lot. Don’t look at me like that, he says.

Here’s your walker, she says. She helps him stand. His legs are not too good, very shaky.

This damn knee, he says.

The problem is located a lot higher up than that, she says. Then she says, very scolding-voiced, where are you going?

I thought I would just go — he stops. He can’t remember. Over there, he says and he starts toward the French doors that lead to the hallway, which features the front door, the stairs, and a short passage lined with unfamiliar photographs, beyond which is the kitchen.

Then what? the younger one says. She’s pretty. He likes her even though she’s not particularly nice. He likes her in those cowboy pants. And the boots. Do you work for the rodeo? he says.

Why do you keep saying that?

Your pants, your pants! he says. Your dungarees. He likes the word, having that word: dungarees! He says it again and points at her crotch.

No I don’t work for the rodeo, she says.

Well you should. You have the right pants.

Where are you going? she says.

I’m looking for the woman who runs this place. I’m hungry. You tell her I need something to eat. Go ahead, tell her.

They are sitting at the table in the dining room, all three. Someone has given him a sandwich and a pickle. He says, this place isn’t as nice as the one up the street. Which one, the young one says. That one, he says, indicating with his head. Up the street! They’re playing ignorant.

The one who runs things says to the rodeo one, he’s very enamored of this imaginary place up the street. To him she says, well, you keep talking about it but you’re going to have to show it to us. If you show it to us we can always drop you off there.

The younger one says, do you know who I am?

Why are they forever asking this? You belong to her, he says and gestures at the older one.

And who is she? his daughter says. Do you know who she is?

He shakes his head at her.

You got me, he says. But she certainly knows who she is, he says. You should ask her. She doesn’t have a doubt in the world.

The older one has risen suddenly and moved to the kitchen doorway. She turns around.

I’m your wife, she says.

I’m not married, he says.

These people don’t understand anything. He is pretty clear in his mind that the war has been over a good few years now and he is certain that he has not married. Yet here he is and she is there and sleeps in the same bed! Well that’s a pretty clear indication, isn’t it. Living in sin. He doesn’t remember. Now the old one has gone away but the younger one is looking at him.

I feel as if I’ve been unplugged from the universe, he says.

I know, she says. You told me.

He stabilizes. He grows accustomed to the house again. The wife has a woman in — the woman commutes two and a half hours up from Brooklyn, by bus, subway, Metro-North, bus again. In the afternoon, back to Brooklyn. Four hours of work and five hours of commute. The wife feels bad about this, but four hours a day is all she can afford. The woman shaves him and helps him bathe but will not cut his hair. She makes him lunch. She’s from Barbados, or no, the wife keeps thinking that, but no, it’s not true, what’s true is that she worked in a hotel in Barbados. She grew up in St. Kitts. She is a Caribbean black who frequently indicates strong disapproval of American blacks, until the wife says one day, well, there are fine people and bad people among every race and nationality. Many more fine than bad. And she says, it’s really something of a miracle, given the ways of the world. She’s been saying this since the days of the Freedom Riders.

The caretaker says, you should come to Brooklyn and show me the fine people. All those miracles. She stops talking about the American blacks.

Around this caretaker he is calm in a way none of the others were able to make him. Almost sensible. He can’t remember her name but he always says when he sees her, where were you? And she always says, I was on the bus. Then I was on the train.

Slow train, he says, and she says, oh they’re all slow. They don’t have any fast trains here anymore.

Freud. He remembers Freud. There was so much Freud when he was coming up. He’d been a chemist but then went back for a Ph.D. in psychology. Freud. Like God Almighty. A giant fad, really, taking up how many lives? A couple hundred thousand certainly. Likely a million or two. It was a fad, basically. No, some of it was important. Some of it mattered a great deal. But a lot of it was some weirdly arrived at doctrine. Which became an inexplicable fad. He says to the one who runs things, it’s all just a fad.

What is? she says.

Oh that thing. What’s the name of that thing they put around their waists?

Belts? she says. This makes him angry.

The daughter is there. He says to the black one, who are all these people?

They are your family, she says. That is your wife. She says a name but he can’t take it in. That is your daughter. Another name.

Cecilia you said?

No, no, she says. Not Cecilia. She says the name again.

Well, Cecilia is a nice name. A name from the litany. St. Cecilia, pray-ay for us. St. Catharine, pray-ay for us. All you holy virgins and widows, pray-ay for us. He croaks this out and it feels good. St. River Street, pray-ay for us, he cries. St. Ford Automobile, pray-ay for us. They are all laughing now and he smiles and says, what’s so funny? Then he starts it again, St. Cecil B. Cecille, pray-ay for us. All you saints of God, be merciful!

Shush you now, the black one says. That’s a unholy racket. She helps him up from the chair, gives him the walker. Let’s go out the back yard, she says.

It takes too long, he says.

No it doesn’t.

What’s out there? Some special bird? Mona the cat?

The young one looks up from her little machine at the table in the dining room. Mona’s been dead for twenty-five years, she says.

Is that in your time machine there? he says. He waves at it, the little aluminum thing.

Nope, she says.

You can’t travel back in time?

Nope, she says.

How do you remember things? he says.

It’s in here. She taps her head.

Oh it’s all in your head, he says. This makes him laugh, a little choke of a laugh. He’d been a psychologist after all. It’s all in your head! That’s what I should have told them.

Who? the young one says.

All of them!

He and the black one move through the dining room into the kitchen, small steps, she a forceful presence just behind him with her hand on his arm; she has big hands, long fingers. From the kitchen they go out the door to the back, down a small step — she takes his walker and puts it out before him, he holds the doorframe and she has his other arm and he steps down, first one foot, then the other. Out back, a stone patio and some chairs.

Is it fall? he says.

Lord no, it’s springtime, she says. Can’t you see all them green leaves and them tulips now?

No. Where are they? The tulips, funny sagging things, bent over as he is. Stooped. But he sees the trio of tall oaks that arch high over the house. The eyes are drawn up by them as in a cathedral, just as high. Or higher. He twists himself to the right from the bent position he now lives in, keeps turning so he can see a little of the sky, and there it is, the leaves, oh yes, the leaves are that pale new green of spring. The sunlight portioned up between them all.

So winter’s over, he says.

Yes, she says. Finally. She says it with a funny emphasis: fi-NAL-ly.

Where are you from? he says to her.

I’m tired of telling you that, she says. You ask me that every day. Here’s what you can remember: I’m from Brooklyn.

No, he says, I’m from Brooklyn — and they don’t talk like that in Brooklyn.

They do now, she says and laughs.

The thought settles into the wife’s mind, unquestioned, a simple thing, as when you pull up the quilt at night: if she falls ill, if she starts herself to fail and can’t take care of him, she will have to find a way to kill him. She cannot pass this on, the daily floodwater responsibilities and expenses. The retirement funds are only going to hold out for so long. But fine, so be it, as long as she is healthy there will be the Social Security for them both, the retirement money for a little while anyway, and his pension from the county.

And the poor people, he says. Who takes care of them?

Excuse me? she says. In his fogged and magical state, he has a patchy clairvoyance, as if he hears what she’s thinking. Or perhaps she’s talking to herself.

The poor people, he says. Who’s on their side?

No one, she says.

There must be someone, he says.

Well not too many, she says.

And all the people in jail? he says. And all the people in the hospitals? Who speaks for them?

I don’t know, she says.

He sings, Lord, save your people!

Shh, she says.

He is quiet for a moment. She begins to doze, then he says, his voice deep and clear, who are you again?

She says, I’m your wife, God help me.

He says, my wife? Well what do you think about that.

I don’t think about it, she says, half into the pillow. Or I think about nothing else. A small bark: her laughter in the dark.

He, too, seems amused. Depends on your point of view, he says. Another pause. You know, he says —

Yes?

He says, I really didn’t know I had a wife.

I know, she says. Sleep is coming, a blackness rising from below. She wants it.

But it’s likely for the best, he says. To love and honor and this day forward. Death does our part.

A hesitation. She’s gotten to where she can almost hear his brain laboring, all the broken parts clacking and clanging.

No, no, wait, he says, that’s not right. . . .

Go to sleep, she says. Go to sleep.

It’s not right, he says.