It is not beyond reason that it is also the psychotic in men that drives them to greatness.

— W. Eugene Smith

Near the end of 1954, at thirty-five, the photographer W. Eugene Smith quit his job at Life magazine, departing an institution that had brought him international fame, publishing his astonishing war photographs and innovative photo essays. His resignation followed years of fighting with his editors over the processing and layout of his pictures. The final battle concerned a spread on Albert Schweitzer, the French-German physician and theologian who had received the Nobel Peace Prize for his humanitarian work in West Africa. Smith saw in Schweitzer something paternalistic and authoritarian, and he wanted the photographs and the language of the story to suggest that. Life was having none of it; conventional thinking at the time had Schweitzer as a living saint, and conventional thinking prevailed.

Seeking freelance work, Smith joined Magnum Photos, the cooperative agency founded after World War II by Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson, among others, and soon he had his first gig: $1,200 (a pleasant $11,000 in 2017 terms) to spend three weeks in Pittsburgh and deliver a hundred prints, a portion of which would be included in a book commemorating the city’s bicentennial. An easy job, following instructions, but Smith never did follow instructions. He was mesmerized by Pittsburgh — its machinery, its soot, its fire, and its life — so he ended up working on the project for more than two years, taking 17,000 photographs and filling his home in Croton-on-Hudson, New York, with prints and layout boards for a planned book of his own that never happened. He stayed awake for days at a time (with the help of amphetamines), harassing at all hours his assistant, his wife, his children, and even their live-in caretaker. After this long, manic siege, Smith split from the family to move into a run-down loft in New York City, where he embarked on another crazy documentary journey (the loft itself). John Morris, the head of Magnum, arranged a $10,000 contract with Life for a selection of the Pittsburgh photographs (a staggering fee, worth more than $90,000 today), but Smith — who was dead broke, who owed thousands of dollars in back property taxes and other debts, and whose family would soon have to move from their home — turned the deal down. As we learn from Jim Hughes’s biography, Shadow and Substance, Morris wrote to Smith’s editor at Life in the aftermath of the debacle, “I think Gene is worth all the anguish. . . . I recognize in him something which I don’t fully comprehend, but simply feel — and feel sure — is there.”

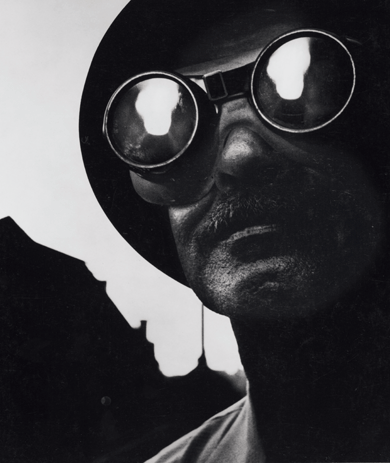

“Steelworker with Goggles,” Pittsburgh, 1955. Courtesy Collection Center for Creative Photography,

University of Arizona © The Heirs of W. Eugene Smith. All photographs by W. Eugene Smith

As his family and colleagues could certainly testify, Smith, one of the greatest photographers of the twentieth century, made sure the anguish never let up. He was born in 1918 in Wichita, Kansas, to a Catholic mother of mean and frugal disposition (the portrait Smith took of her later in life is harrowing for its furious-looking anhedonia) and a father who, when his son was seventeen, shot himself in the local hospital parking lot after six-thirty Mass. By then Smith was regularly contributing images to both of the Wichita daily papers, and after a short stint at Notre Dame, he went to New York to make his living as a photographer. Four decades later, not yet sixty, he died, one of the most admired photographers in the world, with eighteen dollars in the bank and a filthy house full of hungry cats.

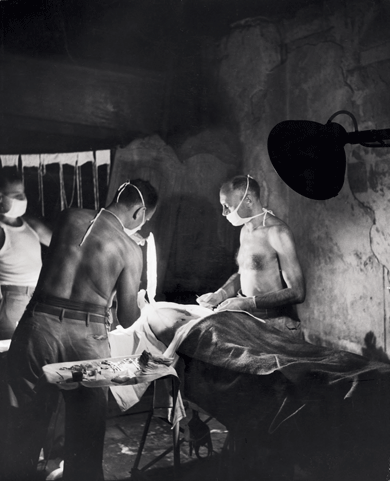

Smith began his career as a precociously competent photojournalist with wondrous technical skills; the startling chiaroscuro that later marked his work showed itself early. Real professional standing and success began to come his way during the war, when he worked for Ziff Davis and then, beginning in 1944, for Life. His photographic sensibility made the emerging genre of the photo essay a perfect vehicle for him, allowing him to push toward something beyond news reporting and the capturing of revealing moments — namely, a technique of documentary storytelling in which the photographs were planned and executed with a complex narrative in mind. (In pursuit of these narratives Smith had no qualms about occasionally posing a photograph — an artifice that, like his bleaching of prints, was later condemned by purists.) His first war-era essay, which features an Army field hospital in a church in the Philippines, appeared in Life in late 1944. The photographs are shockingly elegant, given the subject matter, and technically miraculous, given the darkness inside the church, where the doctors and nurses worked by candlelight. Darkness was, increasingly, Smith’s métier.

“Nettie Smith,” 1947. Courtesy Collection Center for Creative Photography,

University of Arizona © The Heirs of W. Eugene Smith.

In Okinawa in May 1945, Smith, who took horrendous physical risks throughout his career, was badly wounded by a shell explosion; he spent a year recovering, and would be in pain for the rest of his life. In 1946, he resumed his work for Life. His approach to photography was more or less settled: the work would be physically taxing in terms of locations and time, spiritually taxing in terms of the intensity of attention given to the stark realities of human suffering, and technically taxing in terms of how little light he could work with and still create a usable print. His mature style, in other words, was to make everything as difficult as possible. Smith spent many days lying in the Colorado grass to get the opening image for his “Country Doctor” essay of 1948: the doctor on foot, head down, taking a shortcut through the weeds. The image Smith had been waiting for manifested itself one morning as a storm was gathering — the doctor passed by, dark clouds looming almost on top of him, suggesting his emotional burdens and his proximity to death.

Smith’s resignation from Life inaugurated a more private and obsessive phase. The two years he spent working on the Pittsburgh project were followed by his sudden move to Manhattan, to a walk-up on Sixth Avenue that came to be known as the Jazz Loft. He spent his days either in the darkroom or shooting the street outside his windows, and his nights shooting the musicians who gathered after gigs in the loft to jam until daylight. He wired much of the building with microphones hooked up to reel-to-reel recorders and made tapes, not merely of the thousands of hours of music (which now form a substantial contribution to jazz history) but also of the happenstance sounds of his own studio while he worked — his discussions with visitors, his records, what was playing on the radio or the television (ball games, news, even a talk show segment about violence in literature with Tennessee Williams and Yukio Mishima).

The final stage of Smith’s career began in 1971 with what became, politically and historically, his most important project: photographing the residents of Minamata, a coastal city in Japan whose waters and aquatic food supply had been poisoned by mercury dumped by the Chisso Corporation, a chemical giant, leading to birth defects, deformities, and other health problems among the citizens, especially the children, many of whom were exposed in utero to mercury ingested by their mothers. Smith spent two years there; the photographs he took were considered crucial in the court decision that, for the first time, held a Japanese corporation liable for the environmental damage it had caused and the lives it had ruined; they also made Smith into something of a national hero in Japan. Minamata (1975) was the only thematically unified book of photographs Smith published during his lifetime.

Country doctor making a house call, 1947 © The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

The Pittsburgh pictures and those from the Jazz Loft, though less well known than his other work, may be the best that Smith ever did. The art critic John Berger wrote that for Smith, “Pittsburgh represented the human condition at that time. Far more than a city, it was life on this earth. This is why the project grew so uncontrollably.” It wasn’t until the 2001 publication of Dream Street, edited by Sam Stephenson, that the full scope and dramatic force of these photographs were revealed. When Stephenson’s next Smith book, The Jazz Loft Project, came out in 2009, it had an even greater impact, sparking several exhibitions and a series of audio stories by Sara Fishko on NPR that became the basis of her full-length documentary film. Stephenson’s books on Smith, along with the 4,500 hours of audio recordings from the Jazz Loft, which he discovered and raised half a million dollars to have restored and digitized, constitute the fruits of twenty years of research into the photographer’s life and work.

At the outset of his latest book, Gene Smith’s Sink, a kind of off-center biography, Stephenson describes a sidewalk scene in New York City in 1977. From a wheelchair, Smith watches a team of volunteers load the contents of his studio (his “life’s work”) into two 18-wheelers — twenty-two tons in all — to be driven to the University of Arizona, where they would be housed in the newly created Center for Creative Photography.

When the shipment arrived in Tucson, it filled a high school gymnasium and spilled into outlying rooms. The piles were waist-high from wall to wall. . . . Included in the shipment were three thousand matted and unmatted master prints; hundreds of thousands of meticulous 5×7 work prints; hundreds of thousands of negatives and contact sheets . . . and hundreds of boxes of clipped magazine and newspaper articles.

Add to this the multitude of tapes, as well as nearly 4,000 books and 25,000 vinyl records. Much of what we need to know about Smith resides in this unimaginable catalogue: he was maniacally dedicated; he was a profoundly serious artist; and he was, to a degree I’m not expert enough to determine, insane. He was a man who sacrificed everything for his art — including the people around him, who did not ask to be included in such a sacrifice.

Steelworkers in Pittsburgh, 1955. Courtesy Collection Center for Creative

Photography, University of Arizona © The Heirs of W. Eugene Smith

Stephenson refers to Smith as a “bipolar pack rat.” He would know. In 1997, he began poking around the Smith archive, and an obsession was born. It was an obsession with an obsessive — Stephenson’s scholarship and research are full of clanging resonances and occasionally ominous echoes caused by one quasi derangement slapping up against another.

The middle of Smith’s career — the Pittsburgh project and the years in the loft — is where most of Stephenson’s interest lies. Both endeavors were for Smith largely unpaid personal ventures, and they were considered madness or worse by the photographic community. We would understand little of either project, and little of Gene Smith’s true photographic legacy, were it not for Stephenson’s labors. The photographs in these books have a visual fluidity, an improvisational and imaginative sense of humanity, a grandeur, and, frequently, a movement toward abstraction that Smith’s formal essays for Life do not.

Much of Gene Smith’s Sink, in keeping with Stephenson’s documentary training, is oral history. At the same time, the book functions as a memoir of his own years of research into Smith’s life and work, in which Stephenson’s inner life, his actual motivations and aesthetic passions, are hinted at, brushed up against, and occasionally acknowledged, but almost never fully revealed. The majority of the book is made up of the testimony of dozens of near-forgotten musicians and other cultural figures of the era; those voices frequently move the reader who is old enough to know that such a world as New York in the 1950s and early 1960s really existed — reminding us how free it was, how cheap and dingy yet still glamorous and glittering, and how unhealthy, ambitious, and obsessed with art and language and music and image. Unfortunately, the approach Stephenson takes toward himself is not nearly so satisfying; the narrative at several points suggests a writer who is sidestepping revelation more than he is seeking it.

Surgeons tending to a wounded man in the Army field hospital in Cens Cathedral, Leyte, Philippines, 1944 © The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Stephenson, though, talked to almost every living soul he could find from the Pittsburgh and Jazz Loft years. He deciphered the scribbled names of musicians on the boxes of tapes, and with years of effort, he interviewed most of them and dozens of others from the scene. He spoke to Aileen Mioko Smith, the photographer’s second wife and a vital force behind Minamata. They met when she was twenty years old and he was in his early fifties; she quit college to move in and become his helpmate and, soon enough, his wife. Disciplined, committed, and fluent in Japanese, she made Smith’s work in Minamata possible, and it was that project that brought him back professionally from nearly twenty years of failure and rejection. The images captured the mercury pollution still occurring at the fringes of the bay and the public hearings and demonstrations surrounding the victims’ attempts to bring Chisso to justice. Most potent and intimate are the portraits of the victims themselves. Since the war Smith had been fascinated with hands, which often appear in his work in poses suggesting prayer. The hands in the Minamata pictures are frequently deformed, desperate. They haunt you.

Among the Minamata pictures is what Stephenson calls “the greatest photograph of Smith’s career.” Titled “Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath,” it is a pietà, an image swaddled in darkness, showing a small chamber in which one can see two naked figures: a mother in a wooden tub bathing her deformed daughter, Tomoko. Long before Stephenson met her, Aileen, who inherited the rights to the Minamata images, had withdrawn the photograph from circulation because of the pain its frequent reproduction caused the Uemura family. But he had a unique and unexpected opportunity to see it in 2010 at a conference on the hazards of mercury poisoning, where Aileen allowed a large print of the photograph to be displayed because of the public health — as opposed to aesthetic — purpose of the gathering. Stephenson’s encounter with the print comes late in the book and provides one of its more powerful personal moments. The image, Stephenson writes, “caused me to be moved in a manner that I thought had been worn smooth by years of research.”

I came away with a clearer understanding . . . that this print was the culmination of [Smith’s] life and work, all of his passions and interests along with darkroom techniques coming together in one printed picture. No need for a complicated sequence of images. This one would do. His life’s work was complete. It was okay for him to die now.

Everything that comes after this — including Stephenson’s long-planned trip to Japan and Saipan — feels like sweet denouement. He seems to have reached the completion of his own quest to grasp who Gene Smith actually was, as an artist and as a man. It’s not entirely clear, however, that he knows he has done so.

US Marines, Iwo Jima, 1945 (detail) © The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

What Stephenson recognizes is that the Tomoko photograph represents the culmination of the unifying principle driving Smith’s work. It is a principle that seems to me plainly evident in the World War II pictures, in his Life essays, in the Pittsburgh and Jazz Loft photographs. Smith, Berger wrote, was “the most religious photographer in the history of the art. A seer in both the photographic and biblical senses of the term.” That unifying principle is human sympathy of a rare and difficult, almost destructive intensity — starkly expressive, forever unflinching, and never forgetful of the beauty of the visible world.

Gene Smith’s Sink is titled such because, in 2006, Stephenson bought from Smith’s son, Patrick, a collection of Smith’s old equipment, including the sink from the Jazz Loft darkroom, which he converted into a writing desk. The notion of Stephenson re-creating Smith, reenacting him, is an essential part of the book: one senses that Stephenson’s twenty years of research share the same obsessive quality of Smith’s years of making tens of thousands of negatives and prints, years in which nothing could be finished, the years that most occupy Stephenson’s biographical attention. At the end of the book, we find Stephenson driving to Oxford, Mississippi, and New Orleans to explore, to taste, and to smell the worlds of William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams, two writers who were important to Smith. He listens along the way to the audiobook of Light in August, read by the actor Will Patton. Nothing fully exists until it’s been interviewed, so Stephenson decides to find Patton. “Reading Light in August for the microphone was a process of letting that book move through me,” the actor tells him. “It enters your brain and your heart and comes out through your voice. It’s a very intense experience. You live the book. It’s a great privilege to be inside a work of art like that.”

Thelonious Monk with his band, 1959. Courtesy the Jazz Loft Project at the Center for Documentary Studies, Duke University

In response to this, Stephenson, who has spent two decades immersed in Smith’s life and work, makes a most curious statement:

I couldn’t live through Smith’s photographs in the way Patton did Faulkner’s words. Photography is a different medium, the outcomes meant to be looked at, not so much performed.

Instantly, I disagreed. The photographer’s work gets inside you just as words and music and other aesthetic achievements do, and it affects the way you see. Look long enough, and like Cortázar’s man staring at the axolotls (and like Stephenson researching Smith), you suddenly find yourself transported from the outside, looking in, to the inside, looking out. Yet after all these years living under the weight of Gene Smith and trying to get inside him, Stephenson seems to be lamenting that he cannot abide that pain or make sense of that life, with its tremendous messes and spilled chemicals and broken bones. Smith remains for Stephenson a shadow, forcefully occupying the center of a book that has looked in detail at everything around him. And Stephenson himself appears to us as a second shadow: a fleeting figure on the move, unlike Smith, who is stilled by history. We get hints, by looking with Stephenson at the life and work of this genius who has possessed him, that Smith’s inner world was a scary place, chaotic, grandiose, sentimental, and furious — strange ground from which, somehow, truth and beauty have grown.

The issue of whether an artist — not merely a good one but a surpassingly committed and important one — remains “worth all the anguish,” when he is destructive to those who work with him and try to help him and love him, is a vexed one, and we prefer not to think about it much. In part this is because our attitude ought to be one thing — we should wish he’d been well and kind and a good parent and spouse — whereas, in reality, faced with his art, which is the product in part of what caused the anguish, we don’t actually wish him changed at all. Thus are we implicated.

Great art requires of the artist no moral rectitude: the made thing is either well made or it is not, judged by its own inherent standards. This is a satisfying argument and the final word on the matter, aesthetically; but it does not get at the nagging paradoxes: that first, we often sense we’re morally implicated, and second, we increasingly experience art as a way of knowing the artist. This sympathetic exposure to another’s sensibility and consciousness is a kind of miniaturized moral act. It is a limited re-creation of what we do in loving others: we try to know as they know, to see as they see. But it’s a difficult intimacy, quite often. Stephenson obviously loves Smith, but I don’t think he ever gets comfortable with that fact.

Smith was technically brilliant, passionately engaged, physically relentless, stylistically innovative, and an indefatigable chronicler of suffering and injustice; he was a man of generous spirit and deep conscience, both of which attitudes visibly governed his images, but he was also a relentlessly manipulative man, hard-raised and violently abandoned, obsessive to a lunatic degree, who was psychologically abusive of those closest to him; he could not be counted on for a solid minute. And so he died in 1978, fifty-nine years old but looking eighty, difficult, often deluded, dependent on amphetamines and alcohol and the charity of friends and colleagues, in body and at least partially in spirit and mind a broken man.

Alas, we’ve heard all this before about great artists, many times; it’s a tired script and no one’s paying real money for it these days. Artists now are smarter than that — we try to stay in shape and not smoke or drink to excess, we eat organic, we keep to our offices and work on our tenure portfolios — and the republic, if we can still call it that, is thoroughly safe from genius. Safe from the likes of Gene Smith, who not only chronicled injustice but expected to change the world. Even worse, he was an artist, motivated by the kind of disciplined madness that led him once to sit exposed in winter for twenty-seven straight hours on the windowsill of his New York City studio, scrutinizing Sixth Avenue below, every five or ten minutes taking a shot because he thought he might find some hint of human truth down there on the cold, middle-gray pavement. A day or more, in nothing warmer than a sweater — a prisoner, you might say, but I cannot imagine feeling so free.