Nobody in academia had ever witnessed or even heard of a performance like this before. In just a few years, in the early 1950s, a University of Pennsylvania graduate student — a student, in his twenties — had taken over an entire field of study, linguistics, and stood it on its head and hardened it from a spongy so-called “social science” into a real science, a hard science, and put his name on it: Noam Chomsky.

At the time, Chomsky was still finishing his doctoral dissertation for Penn, where he had completed his graduate-school course work. But at bedtime and in his heart of hearts he was living in Boston as a junior member of Harvard’s Society of Fellows, and creating a Harvard-level name for himself.

This moment was the high tide of the “scientificalization” that had become fashionable just after World War II. Get hard! Whatever you do, make it sound scientific! Get out from under the stigma of studying a “social science”! By now “social” meant soft in the brain pan. Sociologists, for example, were willing to do anything to avoid the stigma. They tried to observe and record hour-by-hour conversations, meetings, correspondence, even routes taken by individuals, and make the information really hard by converting it into algorithms full of calculus symbols that gave it the look of mathematical certainty. And they failed totally. Only Chomsky, in linguistics, managed to pull it off and turn all — or almost all — the pillow heads in the field rock-hard.

Even before receiving his Ph.D., Chomsky was invited to lecture at Yale and the University of Chicago. He introduced a radically new theory of language. Language was not something you learned. You were born with a built-in “language organ.” It is functioning the moment you come into the world, just the way your heart and your kidneys are already pumping and filtering and excreting away.

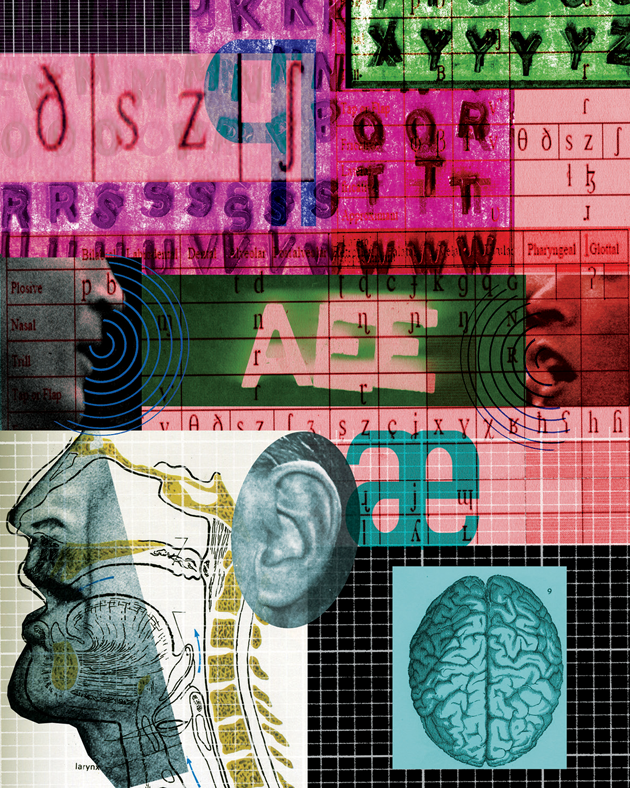

To Chomsky, it didn’t matter what a child’s first language was. Whatever it was, every child’s language organ could use the “deep structure,” “universal grammar,” and “language acquisition device” he was born with to express what he had to say, no matter whether it came out of his mouth in English or Urdu or Nagamese. That was why — as Chomsky said repeatedly — children started speaking so early in life . . . and so correctly in terms of grammar. They were born with the language organ in place and the power ON. By the age of two, usually, they could speak in whole sentences and generate completely original ones. The “organ” . . . the “deep structure” . . . the “universal grammar” . . . the “device” — as Chomsky explained it, the system was physical, empirical, organic, biological. The power of the language organ sent the universal grammar coursing through the deep structure’s lingual ducts to provide nutrition for the LAD, which everybody in the field now knew referred to the “language acquisition device” Chomsky had discovered.

Two years later, in 1957, when he was twenty-eight, Chomsky pulled all this together in a book with the opaque title Syntactic Structures — and was on the way to becoming the biggest name in the history of linguistics. He drove the discipline indoors and turned it upside down. There were thousands of languages on earth, which to earthlings sounded like a hopeless Babel of biblical proportions. That was where Chomsky’s soon-to-be-famous Martian linguist came in. A Martian linguist arriving on earth, he often said . . . often . . . often . . . would immediately realize that all the languages on this planet were the same, with just some minor local accents. And the Martian arrived on earth during almost every Chomsky talk on language.

Only wearily could Chomsky endure traditional linguists who thought fieldwork was essential and wound up in primitive places, emerging from the tall grass zipping their pants up. They were like the ordinary flycatchers in Darwin’s day coming back from the middle of nowhere with their sacks full of little facts and buzzing about with their beloved multi-language fluency. But what difference did it make, knowing all those native tongues? Chomsky made it clear he was elevating linguistics to the altitude of Plato’s transcendent eternal universals. They, not sacks of scattered facts, were the ultimate reality, the only true objects of knowledge. Besides, he didn’t enjoy the outdoors, where “the field” was. He was relocating the field to Olympus. Not only that, he was giving linguists permission to stay air-conditioned. They wouldn’t have to leave the building at all, ever again . . . no more trekking off to interview boneheads in stench-humid huts. And here on Olympus, you had plumbing.

Chomsky had a personality and a charisma equal to Georges Cuvier’s in France in the early 1800s. Cuvier orchestrated his belligerence from sweet reason to outbursts of perfectly timed and rhetorically elegant fury. In contrast, nothing about Chomsky’s charisma was elegant. He spoke in a monotone and never raised his voice, but his eyes lasered any challenger with a look of absolute authority. He wasn’t debating him, he was enduring him. Something about Chomsky’s unchanging tone and visage turned a challenger’s power of reason to jelly.

Young charismatic figures are not a rare breed. In new religious movements they have tended to be the rule, not the exception: Joseph Smith of the Mormons . . . Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha . . . Scientology’s David Miscavige, a “prodigy” and L. Ron Hubbard’s handpicked successor . . . the Báb, forerunner of the Baha’i faith . . . the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ Charles Taze Russell . . . and Moishe Rosen of Jews for Jesus. Likewise in warfare: Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, a seventeen-year-old enlisted man taking over an infantry company in the midst of battle . . . Joan of Arc, a French peasant girl who becomes an army general and the greatest heroine in French history — at the age of nineteen . . . Napoléon Bonaparte, who by the age of twenty-nine had led victories against French Royalist forces as well as the Austrians and the Ottoman Empire . . . Alexander the Great, who had conquered much of the Hellenistic world before his thirtieth birthday . . . William Wallace, Guardian of Scotland, who at twenty-seven led the Scots to victory over the British at the Battle of Stirling Bridge.

Charismatic leaders radiate more than simple confidence. They radiate authority. They don’t tell jokes or speak ironically, except to rebuke — as in “Kindly spare me your ‘originality.’ ” Irony, like plain humor, invariably turns upon some indulgence of human weakness. Charismatic figures show only strength. They refuse to buckle under in the face of threats, including physical threats. They are usually prophets of some new idea or cause.

Chomsky’s idea of the “language organ” created great excitement among young linguists. He made the field seem loftier, more tightly structured, more scientific, more conceptual, more on a Platonic plane, not just a huge heaped-up leaf pile of the data fieldworkers brought in from places one never necessarily heard of before . . . linguistics would no longer mean working out in the field among more breeds of Na — er — indigenous peoples . . . than one ever dreamed existed. Thanks to Chomsky’s success, linguistics rose from being merely a satellite orbiting around language studies and became the main event on the cutting edge. . . . The number of full, formed departments of linguistics soared, as did the numbers of fieldworkers. Fieldwork was no longer a requirement, however, and more linguists than dared confess it were relieved not to have to go into the not-so-great outdoors. Now all the new, Higher Things in a linguist’s life were to be found indoors, at a desk . . . looking at learned journals with cramped type instead of at a bunch of faces in a cloud of gnats.

In a rare recorded instance of someone confronting him over this business of a language organ, Chomsky finessed his way out of it con brio. The writer John Gliedman asked Chomsky the Question. Was he saying he had found a part of human anatomy that all the anatomists, internists, surgeons, and pathologists in the world had never laid eyes on?

It wasn’t a question of laying eyes on it, Chomsky indicated, because the language organ was located inside the brain.

Was he saying that one organ, the language organ, was inside another organ, the brain? But organs are by definition discrete entities. “Is there a special place in the brain and a particular kind of neurological structure that comprises the language organ?” asked Gliedman.

“Little enough is known about cognitive systems and their neurological basis,” said Chomsky. “But it does seem that the representation and use of language involve specific neural structures, though their nature is not well understood.”

It was just a matter of time, he suggested, before empirical research substantiated his analysis. He appeared to be on the verge of the most important anatomical discovery since William Harvey’s discovery of the human circulatory system in 1628.

Soon Noam Chomsky’s reign in linguistics was so supreme, it reduced other linguists to filling in gaps and supplying footnotes for Noam Chomsky. As for any random figure of note who persisted in challenging his authority, Chomsky would summarily dismiss him as a “fraud,” a “liar,” or a “charlatan.” He called B. F. Skinner, Elie Wiesel, and “the American intellectual community” frauds. He called Alan Dershowitz, Christopher Hitchens, and Werner Cohn liars. He pinned the charlatan tag on the famous French psychiatrist Jacques Lacan.

Soon Noam Chomsky’s reign in linguistics was so supreme, it reduced other linguists to filling in gaps and supplying footnotes for Noam Chomsky. As for any random figure of note who persisted in challenging his authority, Chomsky would summarily dismiss him as a “fraud,” a “liar,” or a “charlatan.” He called B. F. Skinner, Elie Wiesel, and “the American intellectual community” frauds. He called Alan Dershowitz, Christopher Hitchens, and Werner Cohn liars. He pinned the charlatan tag on the famous French psychiatrist Jacques Lacan.

Not really very nice — but at least he woke everybody in the field up. All at once academics, even anthropologists and sociologists, discovered the subject of linguistics. Chomsky had provided them the entire structure, anatomy, and physiology of language as a system.

But there remained this baffling business of figuring out just what it was — the creation of the words themselves, the specific sounds and how they were fitted together, the mechanics of the greatest single power known to man . . . How do people do it? . . . and their eyes opened wide as if nobody had ever thought of it before. What would eventually become thousands of articles and conference papers began chundering forth.

One of the most revealing examples of Chomsky’s power was when Roger Wescott, the linguist William Stokoe of Gallaudet University (for the deaf), and the anthropologist Gordon Hewes summed up two decades of writing, separately, about sign language by joining forces and editing Language Origins — with the proud claim that they had filled in a gap in Chomsky’s Syntactic Structures.

And on they came, linguists and anthropologists intent upon shoring up Chomsky’s great edifice with evidence . . . the gestural theory . . . the big brain theory . . . the social complexity theory . . . and . . . and . . .

. . . and more and more scholars sat at their desks just like junior Chomskys trying to solve the mysteries of language with sheer brainpower. The results were not electrifying. Nevertheless, Chomsky had brought the field back to life.

In February of 1967 — bango! — Chomsky shot up clear through the roof of their little world of linguistics and lit up the sky . . . with a 12,000-word excoriation of America’s role in the war in Vietnam entitled “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” The New York Review of Books, the most fashionable organ of the New Left in the Vietnam era, published it as a special supplement.

The piece delivered a shock beyond even Chomsky’s never-modest expectations. From the very first paragraph to the last, he tore into the United States’s “capitalist” rulers, its supine press, its by turns apathetic and pliable intellectuals. He rolled the country over like a big soggy log, exposing the rot rot rot rot on the underside. He accused the United States of “vicious terror bombings of civilians, perfected as a technique of warfare by the Western democracies and reaching their culmination in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, surely among the most unspeakable crimes in history.” And Vietnam? “We can hardly avoid asking ourselves to what extent the American people bear responsibility for the savage American assault on a largely helpless rural population in Vietnam, still another atrocity in what Asians see as the ‘Vasco da Gama era’ ” — meaning imperialist — “of world history. As for those of us who stood by in silence and apathy as this catastrophe slowly took shape over the past dozen years — on what page of history do we find our proper place? Only the most insensible can escape these questions. . . .

The piece delivered a shock beyond even Chomsky’s never-modest expectations. From the very first paragraph to the last, he tore into the United States’s “capitalist” rulers, its supine press, its by turns apathetic and pliable intellectuals. He rolled the country over like a big soggy log, exposing the rot rot rot rot on the underside. He accused the United States of “vicious terror bombings of civilians, perfected as a technique of warfare by the Western democracies and reaching their culmination in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, surely among the most unspeakable crimes in history.” And Vietnam? “We can hardly avoid asking ourselves to what extent the American people bear responsibility for the savage American assault on a largely helpless rural population in Vietnam, still another atrocity in what Asians see as the ‘Vasco da Gama era’ ” — meaning imperialist — “of world history. As for those of us who stood by in silence and apathy as this catastrophe slowly took shape over the past dozen years — on what page of history do we find our proper place? Only the most insensible can escape these questions. . . .

“It is the responsibility of intellectuals,” he said, “to speak the truth and to expose lies. This, at least, may seem enough of a truism to pass over without comment. Not so, however. For the modern intellectual, it is not at all obvious.”

This was an angry god raining fire and brimstone down not merely upon worldlings committing beastly crimes but also upon the anointed angels who had grown soft, corrupt, and silent to the point of complicity with the very forces of Evil it is their sacred duty to protect mankind from.

It was this rebuke of the intellectuals that turned “The Responsibility of Intellectuals” into more than just a provocative essay by an eminent linguist. It became an event, an event on the magnitude of Émile Zola’s J’Accuse in 1898, during the Dreyfus affair in France . . . when Georges Clemenceau, a radical socialist (later prime minister of France — twice), turned the adjective “intellectual” into a noun: “the intellectual.” At that point “the intellectuals” replaced the old term “the clerisy.” Zola, Anatole France, and Octave Mirbeau were the intellectuals uppermost in Clemenceau’s mind, but he by no means restricted that honorific to writers. Anyone involved in any way in the arts, politics, education — even journalism — who discussed the Higher Things from an at least vaguely savory socialist point of view qualified. So from the very beginning the intellectual was a hard-to-define, in fact rather blurry, figure who gave off whiffs — at least that much, whiffs — of Left-aware politics and alienation of some sort.

Chomsky proved to be perfect for the role, and not just because of his academic charisma. More important was timing. He knew how to exploit a tremendous stroke of luck: another war! — this one in a little country in Southeast Asia. It was a small war compared to World War II, but the jolt it gave universities and colleges in America was just as severe. The draft had been reinstated. Male students rose up in protest and the girls tagged along with them and faculty members sang along with them through every last bar of their anthem, “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” (to be replaced two years later with “Give Peace a Chance”). In 1967 tremendous pressure, social pressure, began to build up among the intellectuals to prove they were more than spectators in the grandstand cheering the brave members of the Movement on. The time had come to prove you were an “activist,” i.e., a brave intellectual willing to leave the office, go to the streets, and take part in antiwar demonstrations. The pressure on figures like Chomsky, who was only thirty-eight, was intense. And he did his part, left the building, and marched in the most publicized demonstration of all, the March on the Pentagon in 1967. He proved he was the real thing. He got himself arrested and wound up in the same cell with Norman Mailer, who was an “activist” of what was known as the Radical Chic variety. A Radical Chic protester got himself arrested in the late morning or early afternoon, in mild weather. He was booked and released in time to make it to the Electric Circus, that year’s New York nightspot of the century, and tell war stories. Chomsky cofounded an organization called Resist and got himself arrested so many times that his wife was afraid MIT would finally get tired of it and can him. She began studying linguistics herself, formally, so that she might teach and at least keep bodies and souls together in the family.

No one seemed to realize it, but the antiwar movement had brought out in Chomsky some real-enough political convictions from his childhood, ideas long since dried up and irrelevant — one would have thought. Chomsky was born and raised in Philadelphia, but his parents were among tens of thousands of Ashkenazic Jews who fled Russia following the assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881. Jewish anarchists were singled out (falsely) as the assassins, setting off waves of the bloodiest pogroms in history.

Anarchism had been a logical enough reaction. The word “anarchy” literally means “without rulers.” The Jewish refugees from Russian racial hatred translated that as not merely no more czars . . . but no more authorities of any sort . . . no public officials, no police, no army, no courts of law, no judges, no jailors, no banks — no money — no financial system at all . . . in short, no government . . . and no social classes, either. The dream was of a land made up entirely of communes (not terribly different from the hippie communes of the United States in the 1960s).

A dream it was . . . a dream . . . and talk talk talk it was, and endless theory theory theory, until — ¡milagroso! ¡maravilla! — more than half of a major nation, Spain, was taken over by anarchist cooperativas during the first years, 1936–1938, of the Spanish Civil War . . . when the Loyalists, as they were known, were in power. In 1939 General Francisco Franco and his forces crushed the Loyalists in one of their last strongholds, Barcelona, leading to the memorable gob-of-guilt-in-your-eye cry, “Where were you when Barcelona fell?”

Noam Chomsky, all ten years of him, was in Philadelphia when Barcelona fell. He was so worked up about it that it was the topic of his first published article . . . for the student newspaper of the Deweyite progressive school he went to . . . a piece in which he denounced Franco as a fascist. His political outlook — anarchism — appears to have been set, fixed forever, at that moment. Or perhaps the word is pre-fixed . . . pre-fixed in a shtetl in Russia half a century before he was born. Then, at thirty-eight years old, he laced “The Responsibility of Intellectuals” with so much Marxist lingo that people took him to be part of the radical Left, if not an outright Communist. But he routinely denounced the Soviet Union and Marxism–Leninism as well as capitalism and the United States. He was above their tawdry battles. An angry god was speaking from a higher plane.

Chomsky’s audacity and his exotic Old World, Eastern European slant on life were things most intellectuals found charming, since by then, 1967, opposition to the war in Vietnam had become something stronger than a passion . . . namely, a fashion, a certification that one had risen above the herd. This set off what economists call the multiplier effect. Chomsky’s politics enhanced his reputation as a great linguist, and his reputation as a great linguist enhanced his reputation as a political solon, and his reputation as a political solon inflated his reputation from great linguist to all-around genius, and the genius inflated the solon into a veritable Voltaire, and the veritable Voltaire inflated the genius of all geniuses into a philosophical giant . . . Noam Chomsky.

Even in academia it no longer mattered whether one agreed with Chomsky’s scholarly or political opinions or not . . . for fame enveloped him like a golden armature.

The superlatives came pouring forth from 1967 on. In 1979 a Sunday New York Times review of Chomsky’s Language and Responsibility (Paul Robinson’s “The Chomsky Problem”) began: “Judged in terms of the power, range, novelty and influence of his thought, Noam Chomsky is arguably the most important intellectual alive today.” In 1986, in the Arts & Humanities Citation Index, which tracks how often authors are mentioned in other authors’ work, Chomsky came in eighth . . . in very fast company . . . the first seven were Marx, Lenin, Shakespeare, Aristotle, the Bible, Plato, and Freud. The Prospect–Foreign Policy world thinkers poll for 2005 found Chomsky to be the number-one intellectual in the world, with twice the polling numbers of the runner-up (Umberto Eco). In the New Statesman’s 2006 “Heroes of Our Time” listings — the heroes being mainly fighters for justice and civil rights who had been imprisoned for the Cause, such as Nelson Mandela, the Nobel Peace Prize winner (1993) who had served twenty-seven years of a life sentence for plotting the violent overthrow of the South African government, and another Nobel winner, Aung San Suu Kyi, who was under house arrest in Myanmar at the time — Chomsky came in seventh. His arrests were of the token variety that seldom caused the miscreant to miss dinner out. But his status made up for the never-lost time. A New Yorker profile of Chomsky in 2003 entitled “The Devil’s Accountant” called him “one of the greatest minds of the twentieth century and one of the most reviled.” In 2010 the Encylopaedia Britannica put him on the roster in their book The 100 Most Influential Philosophers of All Time, along with Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Confucius, Epictetus, St. Thomas Aquinas, Moses Maimonides, David Hume, Schopenhauer, Rousseau, Heidegger, Sartre . . . in other words, the greatest minds in the history of the world. This wasn’t fast company, it was a roster of the immortals.

In his new role as an eminence, Chomsky hurled thunderbolts at malefactors down below, ceaselessly, at an astonishing rate . . . 118 books, with titles such as Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (coauthored by Edward S. Herman) . . . Hegemony or Survival: America’s Quest for Global Dominance . . . Profit over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order . . . Failed States (very much including the United States): The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy . . . an average of 1.9 books per year . . . 271 articles, at a rate of 4.3 per year . . . innumerable speaking engagements, which finally got him out of the building and onto airplanes and before podiums far away.

At the same time his output of linguistic papers continued apace, climaxing in 2002 with his and two colleagues’ theory of recursion. Recursion consists, he said, of putting one sentence, one thought, inside another in a series that, theoretically, could be endless. For example, a sentence such as “He assumed that now that her bulbs had burned out, he could shine and achieve the celebrity he had always longed for.” Tucked inside the one thought beginning “He assumed” are four more thoughts, tucked inside one another: “Her bulbs had burned out,” “He could shine,” “He could achieve celebrity,” and “He had always longed for celebrity.” So five thoughts, starting with “He assumed,” are folded and subfolded inside twenty-two words . . . recursion . . . On the face of it, the discovery of recursion was a historic achievement. Every language depended upon recursion — every language. Recursion was the one capability that distinguished human thought from all other forms of cognition . . . recursion accounted for man’s dominance among all the animals on the globe.

Recursion! . . . it was not just a theory, it was a law! — just like Newton’s law of gravity. Objects didn’t fall at one speed in most of the world . . . but slower in Australia and faster in the Canary Islands. Gravity was a law nothing could break. Likewise, recursion! . . . it was a newly discovered law of life on earth . . . recursion! . . . it was the sort of thing that could lift one up to a plateau on Olympus alongside Newton, Copernicus, Galileo, Darwin, Einstein — Noam Chomsky.

By 2005, Noam Chomsky was flying very high. In fact, very high barely says it. The man was . . . in . . . orbit. He had made over an entire field of study in his own likeness. He had discovered and, as linguistics’ reigning authority, decreed the Law of Recur —

OOOF! — right into the solar plexus! — a 13,000-word article in the August–October 2005 issue of Current Anthropology entitled “Cultural Constraints on Grammar and Cognition in Pirahã” by one Daniel L. Everett. Pirahã was apparently a language spoken by several hundred — estimates ranged from 250 to 500 — members of a tribe, the Pirahã (pronounced Pee-da-hannh), isolated deep within Brazil’s vast Amazon basin (2,670,000 square miles, about 40 percent of South America’s entire landmass). Ordinarily, Chomsky was bored brainless by all those tiny little languages that old-fashioned flycatchers like Everett were still bringing back from out in “the field.” But this article was an affront aimed straight at him, by name, harping on two points: first, this particular tiny language, Pirahã, had no recursion, none at all, immediately reducing Chomsky’s law to just another feature found in most languages; and second, it was the Pirahã’s own distinctive culture, their unique ways of living, that shaped the language — not any “language organ,” not any “universal grammar” or “deep structure” or “language acquisition device” that Chomsky said all languages had in common.

It was unbelievable, this attack! — because Chomsky remembered the author, Daniel L. Everett, very well. At least twenty years earlier, in the 1980s, Everett had been a visiting scholar at MIT after working toward a Sc.D. in linguistics from Brazil’s University of Campinas (Universidade Estadual de Campinas). He was a starstruck Chomskyite at the time.1 He had an office right across the hall from Chomsky himself. In 1983 Everett received his doctorate from Campinas after writing his dissertation along devout Chomskyan lines, and he didn’t stop there. In 1986 he rewrote the dissertation into a 126-page entry in the Handbook of Amazonian Languages. It was very nearly an homage to Chomsky. Now that he had his Sc.D. he took periodic breaks in his work with the Pirahã to teach at Campinas, at the University of Pittsburgh as chairman of the linguistics department, and at the University of Manchester in England, where he was professor of phonetics and phonology when he wrote his fateful paper on the Pirahã’s cultural restraint for Current Anthropology.

In his twenty-two years as an off-and-on faculty member, he had written three books and close to seventy articles for learned journals, most of them about his work with the Pirahã. But this was his first bombshell. It was one of the ten most cited articles in Current Anthropology’s fifty-plus-year history.

In his twenty-two years as an off-and-on faculty member, he had written three books and close to seventy articles for learned journals, most of them about his work with the Pirahã. But this was his first bombshell. It was one of the ten most cited articles in Current Anthropology’s fifty-plus-year history.

The blast set off no Ahahhs! within the field, however. Quite the opposite. Noam Chomsky and his Chomskyites were the field. Everett struck them as a clueless outsider who crashes the party of the big thinkers. Look at him! Everett was everything Chomsky wasn’t: a rugged outdoorsman, a hard rider with a thatchy reddish beard and a head of thick thatchy reddish hair. He could have passed for a ranch hand or a West Virginia gas driller. But of course! He was an old-fashioned flycatcher inexplicably here in the midst of modern air-conditioned armchair linguists with their radiation-bluish computer-screen pallors and faux-manly open shirts. They never left the computer, much less the building. Not to mention Everett’s personal background . . . he was from a too small, too remote, too hot — it averaged one hundred degrees from June to September and occasionally hit 115 — too dusty, too out-of-it California town called Holtville, way down near the Mexican border. His father was a sometime cowboy and all-the-time souse and roustabout. He and Everett’s mother had gotten married in their teens and broke up when Everett was not yet two years old. When he was eleven, his mother was in a restaurant staggering beneath a tray full of dirty dishes when she collapsed with a crash and died from an aneurysm.

His father returned from time to time and tried to do his best for his son. His “best” consisted of the lessons of life he taught him, such as taking the boy, who was fourteen at the time, to a Mexican whorehouse to lose his virginity . . . and then banging on the whore’s door and yelling to his son, “Jesus H. Christ, what’s keeping you?” . . . it being his, Dad’s, turn next.

Helpless, hopeless, the boy went with the flow into the loose louche lysergic life of teenagers in the 1960s. He had just swallowed some LSD in a Methodist church — wondering what it would be like to experience acid zooms amid the curlicued decorations of the sanctuary — when he came upon a beautiful girl named Keren, about his age, with raven hair and ravishing lips. He fell so madly in love — what did it matter that she also had a willpower as blindingly bright and unbending as stainless steel?

She straightened him out very fast. She turned out to be a real Methodist. Her mother and father were missionaries. She made a convert out of Everett in no time. Like Everett’s own parents, he and Keren got married in their late teens. Keren revved him up to an evangelical Methodist, and they resolved to head out into the world as missionaries, like Keren’s parents. They underwent several years of intensive linguistic training at the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, founded by a popular late-nineteenth-century evangelist, Dwight Moody, and the Summer Institute of Linguistics, headed by a later evangelical Christian, Ken Pike. These were tough, rigorous academies, with no fooling around. The Summer Institute’s program included four months of survival training for life in the jungle, among other dangerous terrains, as well as advanced instruction in various tribal tongues. The purpose of the Moody Institute and the SIL, as the Summer Institute of Linguistics was called, was to produce missionaries who could convey to prospective converts the Word — the story of Jesus — in their own languages, anywhere on God’s earth.2

Everett had turned out to be such a remarkably adept student, the SIL encouraged him to see what he could do with the Pirahã, a tribe that lived in isolation way up one of the Amazon’s nearly 15,000 tributaries, the Maici River. Other missionaries had tried to convert the Pirahã but could never really learn their language, thanks to highly esoteric constructions in grammar, including meaningful glottal stops and shifts in tone, plus a version consisting solely of bird sounds and whistles . . . to fool their prey while out hunting.

It took three years, but Everett finally mastered it all, even the bird-word warbling, and became, so far as is known, the only outsider who ever did. Pirahã was a version of the Mura tongue, which seemed to have vanished everywhere else. The Pirahã were isolated geographically. They had no neighbors to threaten them . . . or change them. It dawned on Everett that he had come upon a people who had preserved a civilization virtually unchanged for thousands, godknew-how-many thousands, of years.

They spoke only in the present tense. They had virtually no conception of “the future” or “the past,” not even words for “tomorrow” and “yesterday,” just a word for “other day,” which could mean either one. You couldn’t call them Stone Age or Bronze Age or Iron Age or any of the Hard Ages because the Ages were all named after the tools prehistoric people made. The Pirahã made none. They were pre-toolers. They had no conception of making something today that they could use “other day,” meaning tomorrow in this case. As a result, they made no implements of stone or bone or anything else. They made no artifacts at all — with the exception of the bow and arrow and a scraping tool used to make the arrow. So far no one has been able to figure out how the bow and arrow — an artifact if there ever was one — became common to the Inuit at the North Pole, the Chinese in East Asia, to the Indians — er — Native-born in North America, and the Pirahã in Brazil.

Occasionally, some Pirahã would sling together crude baskets of twigs and leaves. But as soon as they delivered the contents, they’d throw the twigs and leaves away. Likewise . . . housing. Only a few domiciles had reached the hut level. The rest were lean-tos of branches and leaves. Palm leaves made the best roofing — until the next strong wind blew the whole thing down. The Pirahã laughed and laughed and flung together another one . . . here in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Pirahã was a language with only three vowels (a, o, i) and eight consonants (p, t, b, g, s, h, k, and x, which is the glottal stop). It was the smallest and leanest language known. The Pirahã were illiterate — not only lexically but also visually. Most could not figure out what they were looking at in two-tone, black-and-white photographs, even when they depicted familiar places and faces. In the Pirahã, Everett could see he had before him the early history of speech and visual deciphering and, miraculously, could study them alive, in the here and now. No such luck with mathematics, however. The Pirahã had none. They had no numbers, not even 1 and 2; only the loose notion of “a little” and “a lot.” Money was a mystery to them. They couldn’t count and hadn’t the vaguest idea of what counting was. Every night for eight months — at their request — Everett had tried to teach them numbers and counting. They had a suspicion that the Brazilian river traders, who arrived regularly on the Maici, were cheating them. A few young Pirahã seemed to be catching on. They were beginning to do real mathematics. The elders sent them away as soon as they noticed. They couldn’t stand children making them look bad. So much for math on the Maici. They had to continue paying the traders with vast quantities of Brazil nuts, which they gathered from the ground in the jungle. They were hunter-gatherers, as the phrase goes, but the hunting didn’t do them much good in the river trade. They had no clue about smoking or curing meat.

Because they had little conception of “the past,” the Pirahã also had little conception of history. Everett ran into this problem when he tried to tell them about Jesus.

“How tall is he?” the Pirahã would ask.

Well, I don’t really know, but —

“Does he have hair like you?” meaning red hair.

I don’t know what his hair was like, but —

The Pirahã lost interest in Jesus immediately. He was unreal to them. “Why does our friend Dan keep telling us these Crooked-Head stories?” The Pirahã spoke of themselves as the Straight Heads. Everybody else was a Crooked Head, including Everett and Keren — and how could a Crooked Head possibly improve the thinking of a Straight Head? After about a week of Jesus, one of the Pirahã, Kóhoi, said to Everett politely but firmly, “We like you, Dan, but don’t tell us anymore about this Jesus.” Everett paid attention to Kóhoi. Kóhoi had spent hours trying to teach him Pirahã. Neither Everett nor Keren ever converted a single Pirahã. Nobody else ever did, either.

The Pirahã lost interest in Jesus immediately. He was unreal to them. “Why does our friend Dan keep telling us these Crooked-Head stories?” The Pirahã spoke of themselves as the Straight Heads. Everybody else was a Crooked Head, including Everett and Keren — and how could a Crooked Head possibly improve the thinking of a Straight Head? After about a week of Jesus, one of the Pirahã, Kóhoi, said to Everett politely but firmly, “We like you, Dan, but don’t tell us anymore about this Jesus.” Everett paid attention to Kóhoi. Kóhoi had spent hours trying to teach him Pirahã. Neither Everett nor Keren ever converted a single Pirahã. Nobody else ever did, either.

The Pirahã had not only the simplest language on earth but also the simplest culture. They had no leaders, let alone any form of government. They had no social classes. They had no religion. They believed there were bad spirits in the world but had no conception of good ones. They had no rituals or ceremonies at all. They had no music or dance whatsoever. They had no words for colors. To indicate that something was red they would liken it to blood or some berry. They made no jewelry or other bodily ornaments. They did wear necklaces . . . lumpy asymmetrical ones intended only to ward off bad spirits. Aesthetics played no part — not in dress, such as it was; not in hairstyles. In fact, the very notion of style was foreign to them.

Here, now, in the flesh, was the type of society that Chomsky considered ideal, namely, anarchy, a society perfectly free from all the ranking systems that stratified and stultified modern life. Well . . . here it is! Go take a look! If it left at some unlikely hour before dawn, you could catch an American Airlines flight from Logan International Airport, in Boston, to Brasília and from Brasília, a Cessna floatplane to the Maici River . . . you could see your dream, anarchy, walking . . . in the sunset.

Chomsky wasn’t even tempted. For a start, it would mean leaving the building and going out into the abominable “field.” But mainly it would be a triumph for Everett and a humiliation for himself, headlined:

Everett to Chomsky:

come meet the tribe

that ko’d your theory

Chomsky never willingly mentioned Everett by name after that, nor did he expound upon the Amazon tribesmen everybody else in linguistics and anthropology was suddenly talking about. He didn’t particularly want to hear about the Pirahã lore that so fascinated other people, such as the way they said good night, which was “Don’t sleep — there are snakes.”

And there were snakes . . . anacondas thirty feet long and weighing five hundred pounds, often lurking near the banks in the shallows of the Maici, capable of coiling themselves around jaguars — and humans — and crushing them and swallowing them whole . . . lancehead pit vipers, whose bite injects a hemotoxin that immediately causes blood cells to disintegrate and burst, making it one of the deadliest snakes in the world . . . heavy-bodied tree boas that can descend from the branches above and suffocate human beings . . . plus various deadly amphibians, insects, and bats . . . black caimans, which are gigantic alligators up to twenty feet long with jaws capable of seizing monkeys, wild pigs, dogs, and now and again humans and forcing them underwater to drown them and then, like anacondas, swallowing them whole . . . Brazilian wandering spiders, as they are called, if not the most venomous spiders on earth, close to it . . . golden poison dart frogs — poisonous frogs! — swollen with enough venom to kill ten humans . . . inch-long cone-nose assassin bugs, also known as kissing bugs because of their habit of biting humans on the face, transmitting Chagas’ disease and causing about 12,500 deaths a year . . . nocturnal vampire bats that can drink human blood for as long as thirty minutes at a time while the human victims sleep.

Walking barefoot or in flip-flops at night in Pirahã land was a form of Russian roulette . . . and so the Pirahã had learned to be light sleepers. Long middle-of-the-night conversations were not uncommon, so wary were they throughout the midnight hours.

Whatever else it was, Everett’s revelation of life among the Pirahã was sensational news in 2005. He had decided not to publish it in any of the leading linguistics journals. Their circulations were too small. Instead he chose Current Anthropology, which was willing to publish the entire article, uncut. That took up a third of the August–October 2005 issue and included eight formal comments solicited from scholars around the world — France, Brazil, Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, the United States — all of it together totaling 25,000 words. In Everett’s case, two of the scholars, Michael Tomasello and Stephen Levinson, were affiliated with the prestigious Max Planck Institute. By no means were their comments — or any others — valentines. They all had their reservations about this and that. So much the better. The big academic presentation paid off. Radio, television, and the popular press picked up on it here and abroad. Germany’s biggest and most influential magazine, Der Spiegel, said the Pirahã, a “small hunting and gathering tribe, with a population of only 310 to 350, has become the center of a raging debate between linguists, anthropologists and cognitive researchers. Even Noam Chomsky of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Steven Pinker of Harvard University, two of the most influential theorists on the subject, are still arguing over what it means for the study of human language that the Pirahãs don’t use subordinate clauses.”

The British newspaper the Independent zeroed in on recursion. “The Pirahã language has none of [recursion’s] features; every sentence stands alone and refers to a single event. . . . Professor Everett insists the example of the Pirahã, because of the impact their peculiar culture has had upon their language and way of thinking, strikes a devastating blow to Chomskian theory. ‘Hypotheses such as universal grammar are inadequate to account for the Pirahã facts because they assume that language evolution has ceased to be shaped by the social life of the species.’ The Pirahã’s grammar, he argues, comes from their culture, not from any pre-existing mental template.”

The New Scientist said, “Everett also argues that the Pirahã language is the final nail in the coffin for Noam Chomsky’s hugely influential theory of universal grammar. Although this has been modified considerably since its origins in the 1960s, most linguists still hold to its central idea, which is that the human mind has evolved an innate capacity for language and that all languages share certain universal forms that are constrained by the way that we think.”

In academia scholars are supposed to think and write at a level far above the excitement of the popular media. But Everett and his Pirahã publicity got so deeply under the scholars’ skin, they couldn’t stand it any longer. In 2006, MIT’s cognitive science department — not Noam Chomsky’s linguistics department — invited Everett to give a lecture about the “cultural factors” that made the Pirahã and their language so exceptional. Three days beforehand, a diatribe appeared on all the Listservs usually reserved for notices about talks to the MIT linguistics community, calling Everett a shameless out-and-out liar who falsifies evidence to support his claims concerning the Pirahã and their language. In fact, says the writer, Everett is so utterly shameless that he had already written about this small Amazonian tribe twenty years earlier in his doctoral dissertation . . . and is now blithely and brazenly contradicting himself whenever he feels like it. I’m publishing all this ahead of time, says the writer, for fear I and others who see through Everett’s scam will be “cut off” if we try to expose him at the event itself. In his peroration he says, eyeteeth oozing with irony:

“You, too, can enjoy the spotlight of mass media and closet exoticists! Just find a remote tribe and exploit them for your own fame by making claims nobody will bother to check!” It turned out to be by Andrew Nevins, a young, newly hired linguist at Harvard. He couldn’t hold it in any longer!

Nobody in the used-to-be-seemly field of linguistics or any other discipline had ever seen a performance like this before.

Nevins was at work with two other linguists, David Pesetsky and Cilene Rodrigues, on an article so long — 31,000 words — that it was the equivalent of over 110 pages in a dense, scholarly book. They fought Everett point by point, no matter how dot-size the point. The aim, obviously, was to carpet bomb, obliterate, every syllable Everett had to say about this miserable little tribe he claimed he had found somewhere in the depths of Brazil’s Amazon basin. It appeared online as “Pirahã Exceptionality: a Reassessment,” by “Andrew Nevins (Harvard), David Pesetsky (MIT), and Cilene Rodrigues (Universidade Estadual de Campinas)” . . . three linguists from three different universities, Pesetsky pointed out . . . hmmm . . . a bit . . . disingenuously . . . because put them all together . . . they spelled CHOMSKY (MIT). Chomsky had been David Pesetsky’s dissertation supervisor when Pesetsky got his doctoral degree at MIT in 1983. Five years later he returned as Chomsky’s junior colleague on the linguistics faculty. Chomsky’s close friend Morris Halle, the MIT linguist who back in 1955 had played a major role in bringing him to MIT in the first place, became the dissertation supervisor to Andrew Nevins. Nevins was an MIT lifer. He had enrolled as a freshman in 1996 and had been there for nine years by the time he received his Ph.D. in 2004 . . . and married Cilene Rodrigues, a Brazilian linguist who had been a visiting scholar at MIT for several years. What they wrote, “Pirahã Exceptionality: a Reassessment,” couldn’t have seemed more of a Chomsky production had he put his byline on it.

Nevins was at work with two other linguists, David Pesetsky and Cilene Rodrigues, on an article so long — 31,000 words — that it was the equivalent of over 110 pages in a dense, scholarly book. They fought Everett point by point, no matter how dot-size the point. The aim, obviously, was to carpet bomb, obliterate, every syllable Everett had to say about this miserable little tribe he claimed he had found somewhere in the depths of Brazil’s Amazon basin. It appeared online as “Pirahã Exceptionality: a Reassessment,” by “Andrew Nevins (Harvard), David Pesetsky (MIT), and Cilene Rodrigues (Universidade Estadual de Campinas)” . . . three linguists from three different universities, Pesetsky pointed out . . . hmmm . . . a bit . . . disingenuously . . . because put them all together . . . they spelled CHOMSKY (MIT). Chomsky had been David Pesetsky’s dissertation supervisor when Pesetsky got his doctoral degree at MIT in 1983. Five years later he returned as Chomsky’s junior colleague on the linguistics faculty. Chomsky’s close friend Morris Halle, the MIT linguist who back in 1955 had played a major role in bringing him to MIT in the first place, became the dissertation supervisor to Andrew Nevins. Nevins was an MIT lifer. He had enrolled as a freshman in 1996 and had been there for nine years by the time he received his Ph.D. in 2004 . . . and married Cilene Rodrigues, a Brazilian linguist who had been a visiting scholar at MIT for several years. What they wrote, “Pirahã Exceptionality: a Reassessment,” couldn’t have seemed more of a Chomsky production had he put his byline on it.

The problem was, it had taken the truth squad, namely, Nevins, Pesetsky, and Rodrigues, all of 2006 to assemble this prodigious weapon. They planned to submit it to the biggest and most influential linguistics journal, Language, but it could easily take another six or eight months for Language to put it through their meticulous review process. So the trio first decided to post it online on LingBuzz, a linguistics article-sharing site with a large Chomsky following. Their behemoth doomsday rebuttal appeared there on March 8, 2007 —

— and keeled over thirty-nine days later, April 16. On that day, The New Yorker published a 13,000-word piece about Everett entitled “The Interpreter: Has a remote Amazonian tribe upended our understanding of language?” by John Colapinto, with a subhead reading “Dan Everett believes that Pirahã undermines Noam Chomsky’s idea of a universal grammar.” The magazine had sent the writer, Colapinto, down to the Amazon basin with Everett.

In his opening paragraph Colapinto describes how he and Everett arrived on the Maici in a Cessna floatplane. Up on the riverbank were about thirty Pirahã. They greeted him with what “sounded like a profusion of exotic songbirds, a melodic chattering scarcely discernible, to the uninitiated, as human speech.” Colapinto’s richest moment came when the linguist W. Tecumseh Fitch arrived. Fitch was a reverent Chomskyite. He had collaborated with Chomsky and Marc Hauser in writing the 2002 article proclaiming Chomsky’s discovery that recursion was the very essence of human language. Fitch wanted to see the Pirahã for himself, and Everett had said come right ahead. Fitch had devised a test by which he somehow — it was all highly esoteric and superscientifical — could detect whether a person was using “context-free grammar” by filming his eye movements while a cartoon monkey moved this way and that on a computer screen, accompanied by simple audio cues. He was absolutely sure the Pirahã would pass the test. “They’re going to get this basic pattern. The Pirahã are humans — humans can do this.”

Fitch was very open about why he had come all the way from Scotland into the very bowels of the Amazon basin: to prove that, like everybody else, the Pirahã used recursion. At the University of St. Andrews he had left the building a few times to do fieldwork on animal behavior, but never for anything even remotely like this: to study an alien tribe of human beings he had never heard of before . . . well beyond the boundary line of civilization, law and order, in the rainforests of Brazil’s wild northwest.

With Everett’s help he set up a site for his experiments, complete with video and audio equipment. The first subject was a muscular Pirahã with a bowl-shaped haircut. He did nothing but look at the floating monkey head. He ignored the audio cues.

“It didn’t look like he was doing premonitory looking,” i.e., trying to sense what the monkey might do, Fitch said to Everett. “Maybe ask him to point to where he thinks the monkey is going to go.”

“They don’t point,” Everett said. And they don’t have words for “left” or “right” or “over there” or any other direction. You can’t tell them to go up or down; you have to say something concrete such as “up the river” or “down the river.” So Everett asked the man if the monkey was going upriver or downriver.

The man said, “Monkeys go to the jungle.”

Fitch has been described as a “tall, patrician man,” very much the old Ivy League sort. His full name is William Tecumseh Sherman Fitch III. He is a direct descendant of William Tecumseh Sherman, the famous Civil War general. But now with Everett in the Amazon basin, he was sweating, and his brow was beginning to fold into rivulets between his eyebrows and on either side of his nose. He ran the test again. After several abortive tries, Fitch’s voice took on “a rising note of panic, ‘If they fail in the recursion one — it’s not recursion; I’ve got to stop saying that. I mean embedding. Because, I mean, if he can’t get this — ’ ”

In the Amazon basin, the tall patrician is reduced to ejaculations such as “Fuck! If I’d had a joystick for him to hunt the monkey!”

The New Yorker piece made Chomsky furious. It threw him and his followers into full combat mode. He had turned down Colapinto’s request for an interview, apparently to position himself as aloof from his challenger. He and Everett were not on the same plane. But now the whole accursèd world was reading The New Yorker. Dan Everett, The New Yorker called him, Dan, not Daniel L. Everett . . . in the magazine’s eyes he was an instant folk hero . . . Little Dan standing up to daunting Dictator Chomsky.

In the heading of the article was a photograph, reprinted many times since, of Everett submerged up to his neck in the Maici River. Only his smiling face is visible. Right near him but above him is a thirty-five-or-so-year-old Pirahã sitting in a canoe in his gym shorts. It became the image that distinguished Everett from Chomsky. Immersed! — up to his very neck, Everett is . . . immersed in the lives of a tribe of hitherto unknown Na — er — indigenous peoples in the Amazon’s uncivilized northwest. No linguist could help but contrast that with everybody’s mental picture of Chomsky sitting up high, very high, in an armchair in an air-conditioned office at MIT, spic-and-span . . . he never looks down, only inward. He never leaves the building except to go to the airport to fly to other campuses to receive honorary degrees . . . more than forty at last count . . . and remain unmuddied by the Maici or any of the other muck of life down below.

Not that Everett in any way superseded Chomsky. He was far too roundly resented for that. He was telling academics that they had wasted half a century by subscribing to Chomsky’s doctrine of Universal Grammar. Languages might appear wildly different from one another on the surface, Chomsky had taught, but down deep all shared the same structure and worked the same way. Abandoning that Chomskyan first principle would not come easily.

That much was perhaps predictable. But by now, the early twenty-first century, the vast majority of people who thought of themselves as intellectuals were atheists. Believers were regarded as something slightly worse than hapless fools. And the lowest breed of believers was the evangelical white Believer. There you had Daniel Everett. True, he had converted from Christianity to anthropology in the early 1980s — but his not merely evangelical but missionary past was a stain that would never fade away completely . . . not in academia.

That much was perhaps predictable. But by now, the early twenty-first century, the vast majority of people who thought of themselves as intellectuals were atheists. Believers were regarded as something slightly worse than hapless fools. And the lowest breed of believers was the evangelical white Believer. There you had Daniel Everett. True, he had converted from Christianity to anthropology in the early 1980s — but his not merely evangelical but missionary past was a stain that would never fade away completely . . . not in academia.

Even before the term “political correctness” entered the language, linguists and anthropologists were careful not to characterize any — er — indigenous peoples as crude or simpleminded or inferior in any way. Everett was careful and a half. He had come upon the simplest society in the known world. The Pirahã thought only in the present tense. They had a limited language; it had no recursion, which would have enabled it to stretch on endlessly in any direction and into any time frame. They had no artifacts except for those bows and arrows. Everett bent over backwards to keep the Pirahã from sounding the least bit crude or simpleminded. Their language had its limits — but it had a certain profound richness, he said. It was the most difficult language in the world to learn — but such was the price of complexity, he said. Everett expressed nothing but admiration when it came to the Pirahã. But by this time, the early twenty-first century, even giving the vaguest hint that you looked upon some — er — indigenous peoples as stone simple was no longer elitist. The word, by 2007, was “racist.” And racist had become hard tar to remove.

Racist . . . out of that came the modern equivalent of the Roman Inquisition’s declaring Galileo “vehemently suspect of heresy” and placing him under house arrest for the last eight years of his life, making it impossible for him to continue his study of the universe. But the Inquisition was at least wide open about what it was doing. In Everett’s case, putting an end to his life’s work was a clandestine operation. Not long after Colapinto’s New Yorker article appeared, Everett was in the United States teaching at Illinois State University when he got a call from a canary with a Ph.D. informing him that a Brazilian government agency known as FUNAI, the Portuguese acronym for the National Indian Foundation, was denying him permission to return to the Pirahã . . . on the grounds that what he had written about them was . . . racist. He was dumbfounded.

Now he was convinced that the truth squad was waging outright war. He began writing a counterattack faster than he had ever written anything in his life. He didn’t know, but wouldn’t have been surprised to learn, that Nevins, Pesetsky, and Rodrigues were already at work, converting their online carpet bomb on LingBuzz into a veritable hecatomb to run in Language and snuff out Everett’s heresy once and for all.

There was no rushing Language’s editors, however. They found the piece too long. By the time the squad rewrote the piece . . . and Language, never in a hurry, edited it . . . and the article, bearing the old LingBuzz title, “Pirahã Exceptionality: a Reassessment,” seemed far enough along to make Language’s June 2009 issue —

— Everett executed a coup de scoop.

In November of 2008, a full seven months before the truth squad’s scheduled hecatomb time for Everett, he, the scheduled mark, did a stunning thing. He maintained his mad pace and beat them into print — with one of the handful of popular books ever written on linguistics: Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes, an account of his and his family’s thirty years with the Pirahã. It was dead serious in an academic sense. He loaded it with scholarly linguistic and anthropological reports of his findings in the Amazon. He left academics blinking . . . and nonacademics with eyes wide open, staring. The book broke free of its scholarly binding right away.

Margaret Mead had her adventures among the Samoans, and Bronislaw Malinowski had his among the Trobriand Islanders. But Everett’s adventures among the Pirahã kept blowing up into situations too deadly to be written off as “adventures.”

There were more immediate ways to die in the rainforests than anyone who had never lived there could possibly imagine. The constant threat of death gave even Everett’s scholarly observations a grisly edge . . . especially compared to those of linguists who never left their aerated offices in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In the rainforests, mosquitoes transmitting dengue fever, yellow fever, chikungunya, and malaria rose up by the cloudful from dusk to dawn, as numerous as the oxygen atoms they flew through, or so it felt. No matter what precautions you took, if you lived there for three months or more, you were guaranteed infection by mosquitoes penetrating your skin with their proboscises’ forty-seven cutting edges, first injecting their saliva to prevent the puncture from clotting and then drinking your blood at their leisure. The saliva causes the itching that follows.

Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes instantly became a hit and the biggest wallop in the breadbasket Noam Chomsky’s hegemony had ever suffered. Everett didn’t so much attack Chomsky’s theory as dismiss it. He spoke of Chomsky’s waning influence and the mounting evidence that Chomsky was wrong when he called language “innate.” Language had not evolved from . . . anything. It was an artifact. Just as man had taken natural materials, namely, wood and metal, and combined them to create the axe, he had taken natural sounds and put them together in the form of codes representing objects, actions, and, ultimately, thoughts and calculations — and called the codes words. In Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes, Everett animates his avant-garde theory with the story of his own thirty years with the Pirahã . . . risking death in virtually every conceivable form in the jungle, from malaria to murder to poison to getting swallowed by anacondas.

National Public Radio read great swaths of the book aloud over their national network and named it one of the best books of the year. Reviews in the popular press were uniformly favorable, even glowing . . . to the point of blinding . . . as in the Sacramento Book Review: “A genuine and engrossing book that is both sharp and intuitive; it closes around you and reaches inside you, controlling your every thought and movement as you read it.” It is “impossible to forget.”

Ideally, great wide-eyed romantic acclaim like this should have no effect, except perhaps a negative one, in academia. But when the truth squad’s 30,000-word “reassessment” finally came out in Language, in June of 2009, there was no explosion. The Great Rebuttal just lay there, a swollen corpus of objections — cosmic, small-minded, and everything in between. It didn’t make a sound. The success of Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes had defused it.

Chomsky and the squad were far from done for, however. They concentrated on the academic press. No academic, in what was still the Age of Chomsky, was likely to write any gushing review of Everett’s scarlet book. Chomsky and the squad were on the qui vive for anyone who stepped out of line. A professor of philosophy at King’s College London, David Papineau, wrote a more or less positive review of Don’t Sleep — only that: “more or less” — and a member of the truth squad, David Pesetsky, put him in his place. Papineau didn’t take this as good-hearted collegial advice. “For people outside of linguistics,” he said, “it’s rather surprising to find this kind of protection of orthodoxy.”

Three months after Don’t Sleep was published, Chomsky dismissed Everett to the outer darkness with one of his favorite epithets. In an interview with Folha de S. Paulo, Brazil’s biggest and most influential newspaper, news website, and mobile news service, Chomsky said Everett “has turned into a charlatan.” A charlatan is a fraud who specializes in showing off knowledge he doesn’t have. The epithets (“fraud,” “liar,” “charlatan”) were Chomsky’s way of sentencing opponents to Oblivion. From now on Everett wouldn’t rate the effort it would take to denounce him.

Everett had, as it says in the song, let the dogs out. Linguists who had kept their doubts and grumbles to themselves were now emboldened to speak out openly.

Michael Tomasello, a psychologist who was co-director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and one of the scholars who commented on Everett’s 2005 article in Current Anthropology, had been critical of this and that in Chomsky’s theory for several years. But in 2009, after Everett’s book was published, he went all out in a paper entitled “Universal Grammar Is Dead” for the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences and confronted Chomsky head-on: “The idea of a biologically evolved, universal grammar with linguistic content is a myth.” “Myth” became the new word. Vyvyan Evans of Wales’s Bangor University expanded it into a book, The Language Myth, in 2014. He came right out and rejected Chomsky’s and Steven Pinker’s idea of an innate, natural-born “language instinct.” In a blurb, Michael Fortescue of the University of Copenhagen added, “Evans’ rebuttal of Chomsky’s Universal Grammar from the perspective of Cognitive Linguistics provides an excellent antidote to popular textbooks where it is assumed that the Chomskyan approach to linguistic theory . . . has somehow been vindicated once and for all.”

Thanks to Everett, linguists were beginning to breathe life into the words of the anti-Chomskyans of the twentieth century who had been written off as cranks or contrarians, such as Larry Trask, a linguist at England’s University of Sussex. In 2003, the year after Chomsky announced his Law of Recursion, Trask said in an interview, “I have no time for Chomskyan theorizing and its associated dogmas of ‘universal grammar.’ This stuff is so much half-baked twaddle, more akin to a religious movement than to a scholarly enterprise. I am confident that our successors will look back on UG as a huge waste of time. I deeply regret the fact that this sludge attracts so much attention outside linguistics, so much so that many non-linguists believe that Chomskyan theory simply is linguistics . . . and that UG is now an established piece of truth, beyond criticism or discussion. The truth is entirely otherwise.”

In 2012 Everett published Language: The Cultural Tool, a book spelling out in scholarly detail the linguistic material he had tucked in amid the tales of death-dodging in Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes . . . namely, that speech, language, is not something that had evolved in Homo sapiens, the way the breed’s unique small-motor-skilled hands had . . . or its next-to-hairless body. Speech is man-made. It is an artifact . . . and it explains man’s power over all other creatures in a way Evolution all by itself can’t begin to.

Language: The Cultural Tool was Everett’s Origin of Species, his Philosophiae Naturalis . . . and it wasn’t nearly the success that Don’t Sleep had been. It went light on the autobiographical storytelling . . . Oh, the book had its moments . . . Only Everett had it in him to make direct fun of Chomsky . . . He tells a story about visiting MIT in the early 1990s and going to what was billed as a major Chomsky lecture. “A group of his students were sitting in the back giggling,” says Everett. “When Chomsky mentioned the Martian linguist example, they could barely constrain their chuckles and I saw money changing hands.” After the talk, he asked them what that was all about, and they said they had bets with each other on exactly when in his lecture Chomsky would drop his moldy old Martian linguist on everybody.

Critics such as Tomasello and Vyvyan Evans, as well as Everett, had begun to have their doubts about Chomsky’s UG. Where did that leave the rest of his anatomy of speech? After all, he was very firm in his insistence that it was a physical structure. Somewhere in the brain the language organ was actually pumping the UG through the deep structure so that the LAD, the language acquisition device, could make language, speech, audible, visible, the absolutely real product of Homo sapiens’s central nervous system.

And Chomsky’s reaction? As always, Chomsky proved to be unbeatable when it came to debate. He never let himself be backed into a corner, where he could be forced to have it out with his attackers jowl to howl. He either jumped out ahead of them and up above them or so artfully dodged them that they were left staggering off stride. Tomasello had closed in and just about had him on all this far-fetched para-anatomy, when suddenly —

— shazzzzammm — Chomsky’s language organ and all its para-anatomy, if that was what it was, disappeared, as if it had never been there in the first place. He never recanted a word. He merely subsumed the same concepts beneath a new and broader body of thought. Gone, too, astonishingly, was recursion. Recursion! In 2002 Chomsky had announced his discovery of recursion and pronounced it the essential element of human speech. But here, in the summer of 2013, when he appeared before the Linguistic Society of America’s Linguistic Institute at the University of Michigan . . . recursion had vanished, too. So where did that leave Everett and his remarks on recursion? Where? Nowhere. Recursion was no longer an issue . . . and Everett didn’t exist anymore. He was a ghost, a vaporized nonperson. Naturally, the truth squad could no longer see him, either. They couldn’t have cared less about churning up an angry wave for Language: The Cultural Tool to come surfing in on. They didn’t even extend Everett the courtesy of loathing him in print. They left non-him behind with all the rest of history’s roadside trash.

The passage of time did not mollify Chomsky’s opinion of the non-him, Everett, in the slightest. In 2016, when I pressed him on the point, Chomsky blew off Everett like a nonentity to the minus-second power.

“It” — Everett’s opinion; he does not refer to Everett by name — “amounts to absolutely nothing, which is why linguists pay no attention to it. He claims, probably incorrectly, it doesn’t matter whether the facts are right or not. I mean, even accepting his claims about the language in question — Pirahã — tells us nothing about these topics. The speakers of this language, Pirahã speakers, easily learn Portuguese, which has all the properties of normal languages, and they learn it just as easily as any other child does, which means they have the same language capacity as anyone else does.”

As a result, Everett’s new book didn’t begin to kick up the ruckus that Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes had. An entirely new world had been born in linguistics. In effect, Chomsky was announcing — without so much as a quick look back over his shoulder — “Welcome to the Strong Minimalist Thesis, Hierarchically Structured Expression, and Merge.” A regular syllablavalanche had buried the language organ and the body parts that came with it.

Starting in the 1950s, said Chomsky, whose own career had started in the 1950s, “there’s been a huge explosion of inquiry into language. . . . Far more penetrating work is going on into a vastly greater array of theoretical issues. . . . Many new topics have been opened. The questions that students are working on today could not even be formulated or even imagined half a century ago or, for that matter, much more recently. . . .” They are “considering more seriously the most fundamental question about language, namely, what is it.” What is it? With the help of “the formal sciences,” said Chomsky, we can take on “the most basic property of language, namely, that each language provides an unbounded array” of (Chomsky loved “array”) “hierarchically structured expressions . . . through some rather obscure system of thought that we know is there but we don’t know much about it.”

In August of 2014, Chomsky teamed up with three colleagues, Johan J. Bolhuis, Robert C. Berwick, and Ian Tattersall, to publish an article for the journal PLoS Biology with the title “How Could Language Have Evolved?” After an invocation of the Strong Minimalist Thesis and the Hierarchical Syntactic Structure, Chomsky and his new trio declare, “It is uncontroversial that language has evolved, just like any other trait of living organisms.” Nothing else in the article is anywhere nearly so set in concrete. Chomsky et alii note it was commonly assumed that language was created primarily for communication . . . but . . . in fact communication is an all but irrelevant, by-the-way use of language . . . language is deeper than that; it is a “particular computational cognitive system, implemented neurally” . . . there is the proposition that Neanderthals could speak . . . but . . . there is no proof . . . we know anatomically that the Neanderthals’ hyoid bone in the throat, essential for Homo sapiens’s speech, was in the right place . . . but . . . “hyoid morphology, like most other lines of evidence, is evidently no silver bullet for determining when human language originated” . . . Chomsky and the trio go over aspect after aspect of language . . . but . . . there is something wrong with every hypothesis . . . they try to be all-encompassing . . . but . . . in the end any attentive soul reading it realizes that all 5,000 words were summed up in the very first eleven words of the piece, which read:

“The evolution of the faculty of language largely remains an enigma.”

An enigma! A century and a half’s worth of certified wise men, if we make Darwin the starting point — or of bearers of doctoral degrees, in any case — six generations of them had devoted their careers to explaining exactly what language is. After all that time and cerebration they had arrived at a conclusion: language is . . . an enigma? Chomsky all by himself had spent sixty years on the subject. He had convinced not only academia but also an awed public that he had the answer. And now he was a signatory of a declaration that language remains . . . an enigma?

“Little enough is known about cognitive systems and their neurological basis,” Chomsky had said to John Gliedman back in 1983. “But it does seem that the representation and use of language involve specific neural structures, though their nature is not well understood.”

It was just a matter of time, he intimated then, until empirical research would substantiate his analogies. That was thirty years ago. So in thirty years, Chomsky had advanced from “specific neural structures, though their nature is not well understood” to “some rather obscure system of thought that we know is there but we don’t know much about.”

In three decades nobody had turned up any hard evidence to support Chomsky’s conviction that every person is born with an innate, gene-driven power of speech with the motor running. But so what? Chomsky had made the most ambitious attempt since Aristotle’s in 350 b.c. to explain what exactly language is. And no one else in human history had come even close. It was dazzling in its own flailing way — this age-old, unending, utter, ultimate, universal display of ignorance concerning man’s most important single gift.