Portrait Inside My Head and To Show and To Tell

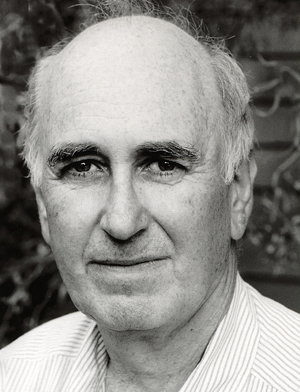

Phillip Lopate on eclectic curiosities and the old-school essayists

Few writers have investigated the complexity of their own minds as thoroughly as Phillip Lopate. For more than thirty years, he has essayed on topics ranging from cinema to the history of Manhattan’s waterfront to his distaste for dinner parties. His newest books, Portrait Inside My Head: Essays and To Show and To Tell: The Craft of Literary Nonfiction, were both released this month from Free Press. The former is a miscellaneous collection; the latter is on the craft and styles of various essayists, and includes the essay “Between Insanity and Fat Dullness: How I became an Emersonian,” originally published in the January 2011 issue of Harper’s Magazine.

Lopate agreed to meet me at his house in Brooklyn on Christmas Eve morning. He greeted me in his living room, which had become a staging area for the imminent arrival of holiday guests, and suggested we go up to his study, a small cube of a room on the top floor that was brimming with books older than me. Among them was a copy of an influential book he’d edited, The Art of the Personal Essay: An Anthology from the Classical Era to the Present (1997), an essential text for upstart essayists and students of writing. I took a seat, and he wheeled his chair close enough for our knees to touch, awaiting my questions.

JG: How do you define your role as an essayist?

PL: I see myself as a transmitter of a tradition. As you can see from the books in my office, I’m far more interested in Max Beerbohm than I am in, say, the latest attempt to hybridize fiction and nonfiction. When I teach, I’m trying to convey my love for Montaigne and Hazlitt and Lamb, Virginia Woolf and James Baldwin and George Orwell. Their sentences excite me tremendously. I can’t help being much more plugged into the past.

I experienced the avant-garde as a kind of bullying influence when I was quite young. I grew up in New York. One of my theories is that native New Yorkers are more traditional and that the avant?garde always comes from the provinces. In the arts, it’s people like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol who believe the hype about New York and come to New York and add to the avant-garde. Whereas a New Yorker tends to say, “Yeah, yeah, OK. Avant-garde, so what?”

When I went to college, I was surrounded by people who were interested in William Burroughs, John Ashbery, Beckett and post-Beckett. The whole sensibility was, “Beckett has done this, now how can we advance his heroic move?” I thought, “Well, maybe I’ll read Henry Fielding.” If I need to experience avant-garde, I’ll read Don Quixote or Tristram Shandy.

From “The State of Nonfiction Today,” in To Show and To Tell: The Craft of Literary Nonfiction:

But if consciousness isolates, it also heals and consoles. In my own writing I am trying to say, among other things, “This is my consciousness, now don’t feel so guilty about yours. If you have perverse, curmudgeonly conflicted, antisocial thoughts; know that others have them too.” (9)

JG: In your new book on craft, To Show and To Tell, you talk about the excitement of essaying sentence by sentence. What advice do you give young writers about crafting a sentence?

PL: My first advice is to immerse yourself in reading — and not just your contemporaries. To investigate syntax and not just to write a simple, clear, seven-word sentence. To some degree, Strunk and White have done a lot of damage by stressing clarity and concreteness as the only important elements in writing. A complex thought requires a complex syntax. It requires semicolons; it requires dependent clauses; it requires following out the thought. For me, it was very helpful to read philosophical writers, because they wanted to think at the highest possible level. I read things like Rilke’s Letters of a Young Poet or Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space. Also Walter Benjamin, Theodore Adorno, Roland Barthes, and Susan Sontag. I became invested in the adventure of the mind. Their sentences tend to be more paradoxical.

One of the things I try to do, which Emil Cioran talks about, is to think against myself, because if you’re just writing to persuade there won’t be any surprises, but if you catch yourself and say, “Yes, but . . .” or, “What’s the other point of view to this?” or, “That’s all very well and good, but so what?” then you create more tension. That’s one of the ways that sentences can get more interesting, if you stage a confrontation between parts of yourself.

JG: Where do you begin your essays?

PL: That’s something I got from Montaigne. He liked to hang out in a mental place where he really didn’t quite understand what he was thinking. He was comfortable with being confused or being aware that he was being pulled in different directions.

I often start out in a place that feels like a baffling cul-de-sac. I think, “How did I get here? What’s going on?” I can’t start out in a self-pleased place because then there’s no tension. There’s no place for the essay to go. I’m often exploring these paradoxes and anomalies inside and outside myself.

JG: How much is tension evoked by the chosen persona on the page?

PL: Max Beerbohm says, “The only people who take themselves very seriously are madmen.” You have to be able to take a step back and have perspective. That is always a trait of the best essayists and memoirists.

One of the reasons autobiographies and memoirs used to be written by older people and not twenty-somethings is that they wanted to be able to look back on the ups and downs of life with some perspective.

JG: Perspective allows the writer to get away with being wrong, right?

PL: Yes, absolutely. One of the strategies of the essay is, “Hey, we’re just a little form here, not the Nobel prize–winning form. So let’s have some fun because we’re not going after the big bucks.” Essay collections are not going to get the big advances. You start out with the form’s tropism toward the small, the minor, the overlooked, the neglected. The persona of the essayist is not one of bluster or megalomania, it’s more one of self-mocking. It’s part and parcel of the genre to have modesty in oneself and perspective. Making fun of yourself is nothing new. It’s a little bit of sugar that makes the essay go down.

JG: In To Show and To Tell you talk about the language of authority. Where does it come from if an essayist should be self-questioning?

JG: In To Show and To Tell you talk about the language of authority. Where does it come from if an essayist should be self-questioning?

PL: That’s the key question of younger writers. “That sounds all well and good, Lopate, but where does your authority come from? How can I do the same thing?” Authority is earned over a long period of time. It’s also attained by bluffing.

I wrote a book called Being With Children (Poseidon, 1989). Afterward I was asked by the New York Times Book Review to review a book about education. My book had been about education, but I realized that for me to pretend to be a reviewer for the New York Times Book Review I would have to invent a persona, invent a character, somebody who felt very comfortable about doing this, which I hadn’t done before. I was also a ghostwriter when I was younger, and that meant I had to inhabit an authority that wasn’t mine. I would pretend to be psychologists, architects, educators, and so on for the guys who hired me. It begins with kind of a fiction. What I was responding to was tone. I was trying to get a tone of authority. That’s something I write about in To Show and To Tell.

While part of the authority comes from aping a certain kind of adult tone, part of it comes from owning your confusion. So you say, “I don’t know this, that means what I do know has extra authority behind it.” You can trust this writer because the writer is telling us that he doesn’t have all the answers. You develop more credibility for the things you do stand behind.

JG: Why did you begin Portrait Inside My Head with an essay titled “In Defense of the Miscellaneous Essay Collection”?

JG: Why did you begin Portrait Inside My Head with an essay titled “In Defense of the Miscellaneous Essay Collection”?

PL: I’m rebelling against a marketing problem, which is that publishers often want you to write about one thing so they can pitch it, so it can be described it in one line. One of the decisions I made in this most recent collection was that I’m going to put in personal essays, literary essays, architectural essays, film essays because all of this is stuff I’m thinking about. I trust that the personality of the writer will hold it together.

Miscellaneous. It’s considered a curse. “Oh, my God! This is just miscellaneous. This is just random.” I’d say, “Yeah, yeah. So? What’s so bad about that?” I’m interested in many different things, most of us are. I’m advocating for that range. Inside my head there’s the lover, the parent, the intellectual, the non-intellectual, and the sports fan. Sometimes sports take up 80 percent of my brain. I wake up in the morning and think, “Who’s on the roster of the New York Knicks?”

JG: What’s the secret engine of your writing?

PL: My engine is curiosity. I’m much more drawn to curiosity than I am to obsession. To me, obsession is someone going on and on in a boring way. Obsession is overrated, but curiosity will take you a long way.

When I wrote my book Waterfront (Anchor, 2005), I had to keep investigating things I knew nothing about, like marine biology, engineering, and the politics of big infrastructure projects. The learning led me through my curiosity until I was able to write something. You don’t have to know everything about it. You just have to know enough to be able to write about it, and in that way the writer and the reporter are similar.

I’m an amateur scholar, a library rat. I didn’t become a professional scholar, but I’m always nibbling at different subjects and trying to learn more about them because I do think that there’s a limit to how much you can write about yourself. You write about your traumas early, and then you’ve used them up.

I often tell my students to develop some expertise and some specialties so that they’ll always be called upon to write about something. It could be bowling; it could be oil production; it could be anything. The point is that you immerse yourself in matter. This is something that writers like Balzac understood. You need material. We’re living in a material universe. We can’t write out of our feelings. We need to understand how things are done, how things are made.

You have to keep taking that self out to explore the world, and that’s one of the key skills, to be able to find the balance between self and the world in your writing. I developed a lot of sub-specialties to do this. They include movies, architecture, urbanism, education, the essay itself, literature in general, so I’m not bothered by writer’s block because there’s always something else that I can write about.

JG: How hard is it to find the balance between the self and the world for you?

PL: Certainly, being able to be alone with yourself and being able to become friends with yourself are very important skills for anybody who wants to write. I’ve known students who were brilliant and verbally very accomplished. They had a hard time just planting their ass in a chair and being alone. It’s not a collaborative art like being a symphony instrumentalist or being a filmmaker. You have to accept the solitude. I am a somewhat gregarious person. That is, I do not ever want to just be home writing. I don’t want it. I use teaching as a source of energy, to replenish me. I’m glad to be able to leave the house sometimes.

There’s this rhythm of going out and coming back. I think of it like an actor’s role. The actor has to be alone in the dressing room then has to go out and perform in front of an audience. He can’t always be onstage. Sometimes professional actors seem very reserved when they’re not acting. They’re not putting out a great deal because when they’re not acting they’re in-gathering.

It isn’t easy for the loved ones of writers. To some degree, when you’re a writer you’re always writing in your head. Sometimes my wife or my daughter will say, “What is that expression on your face? What’s the matter?” I’ll say, “I’m just kind of writing a thing in my head.” It’s thinking. One time my daughter said, “You just sit there in the chair and think?” I said, “Yeah, you should try it some time.”