On Archer’s Underground Comix Roots

How underground comic books helped give rise to Archer

In my review of the animated spy show Archer (FX) in the March issue of Harper’s, I began by tracing the show’s sensibility back to The Simpsons, and to one sequence in particular, the infamous Rake Scene, in which Sideshow Bob steps on nine consecutive rakes (the clip shows only the first few):

By the time the episode aired, I wrote, “The Simpsons had permanently colonized the territory of the absurd and freewheeling.” The show was at the vanguard of the adult animated comedies that emerged in the mid-1990s, helping spawn the anticomedy movement before reaching its apex in Archer’s own razor-sharp, NSFW absurdism:

As you can see, Archer is so outrageous it’s hard to believe the show even airs. Beneath its filthiness, however, lies a recognizable anarchistic urge. To wit: the first-season DVDs of Archer came with an extra advertised as an “unaired pilot.” This was indeed the show’s pilot episode, except that series creators Adam Reed and Matt Thompson had replaced the show’s hero, Sterling Malory Archer, with a green velociraptor, and Archer’s dialogue with dinosaur roars. The second-season DVDs followed up with “Archersaurus: Self-Extinction,” a tone-perfect faux documentary that tracked a now-unemployed Archersaurus’s fall into addiction, homelessness and prostitution, and his eventual demise in a snuff film shot by one of the other characters:

The episode is hilarious and without boundaries, playing with its own forms, the culture, anything onto which it can latch its little mitts. And in its mixture of the crude and whimsical, it goes well beyond anything The Simpsons or even South Park has attempted. (Let’s be honest: filtering everything through childhood and using crude animation also dilutes South Park’s kick.) This isn’t to suggest Archer’s sensibility is entirely sui generis. By my reading, the show’s tone arises from an ancestor older than either of those shows: comic books. And not the ones involving radioactive spiders.

Cartoons for adults — or, rather, for those above the age of consent — are a separate phylum from the one featuring tights and superpowers that was born, in 1933, with a certain do-gooding native of the planet Krypton. Adult cartoons began later, in the exploitative soil of the late Forties and Fifties — in the horror, true crime, and sex and splatter offerings of Entertaining Comics, which published titles like The Vault of Horror, The Haunt of Fear, and A Moon, A Girl . . . Romance, and whose allegedly nefarious influence keyed the 1954 congressional hearings on juvenile delinquency. In 1955, the same year the World Series was first broadcast in color, the comic-book industry implemented a voluntary code of decorum for its issues. Adherence to this code was signaled by a square white seal of approval on the cover, and was mandatory for any drawn-and-stapled book that would be placed on any rack or near any counter where little Tommy might wait for his chocolate malted.

Cartoons for adults — or, rather, for those above the age of consent — are a separate phylum from the one featuring tights and superpowers that was born, in 1933, with a certain do-gooding native of the planet Krypton. Adult cartoons began later, in the exploitative soil of the late Forties and Fifties — in the horror, true crime, and sex and splatter offerings of Entertaining Comics, which published titles like The Vault of Horror, The Haunt of Fear, and A Moon, A Girl . . . Romance, and whose allegedly nefarious influence keyed the 1954 congressional hearings on juvenile delinquency. In 1955, the same year the World Series was first broadcast in color, the comic-book industry implemented a voluntary code of decorum for its issues. Adherence to this code was signaled by a square white seal of approval on the cover, and was mandatory for any drawn-and-stapled book that would be placed on any rack or near any counter where little Tommy might wait for his chocolate malted.

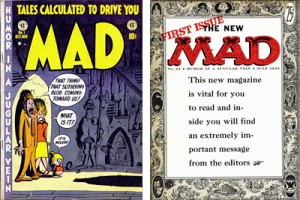

This move might effectively have killed off adult comics, but EC also had a satire title in its stable: Mad. To keep Mad outside the purview of the new code, EC’s owner, William Gaines, worked with an editor named Harvey Kurtzman to transform their nascent comic into a full-sized magazine: sixty-four pages, printed with black ink on a better grade of white paper. With its new business model (and a new grinning, pancake-faced mascot), Mad magazine quickly became required reading for delinquents, hipsters, schnooks, and weisenheimers, more than a few of whom later found their way into colleges and fancy art schools. By the early Sixties, Mad-influenced cartoons had begun popping up everywhere, among them Gilbert Shelton’s drawings in the University of Texas at Austin humor magazine The Texas Ranger; Rick Griffin’s strip “Murphy,” in Surfer; Jack Jackson’s self-published God Nose; and the work of nerdy Robert Crumb, who’d been doodling comics with his brother since they were teens, and who in 1964 put out a twelve-page booklet that included the tale of a horny cat named Fritz.

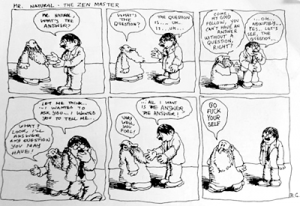

In 1967, Crumb came up with a bald, bearded guru named Mister Natural, a straight-shooting New Age mystic who rejected the material world yet embraced worldly pleasures. Mister Natural first appeared in a six-panel comic, drawn in a detailed but minimalist style with no color applied. “Mr. Natural — The Zen Master” opens with a drawing of a guy in glasses and a suit: “Mr. Natural,” he says, “what’s the answer?” Mister Natural asks what the question is. “All I want is THE ANSWER,” says the guy. “THE ANSWER.”

“Very well you fool!” Mr. Natural answers, turning to walk away. “Go fuck yourself.”

Comix. That sudden x. In 1958 the Motion Picture Association of America slapped Xs on what it determined to be adults-only fare. In the late Sixties, the x provided the fledgling cartooning genre with separation from “legitimate” comic books, the crossed final letter offering both warning and thrill. Inked almost exclusively in black (instead of the usual four colors) and framed by hand-drawn borders, if any (instead of the usual well-defined boxes). Realistic renderings. Surrealistic freakouts featuring weird metaphysical or drugged-out bullshit. Stories about Vietnam, protests, love-ins, biker bars, hallucinogenics, racial hang-ups, the absurdity of the straight world, young men and women trying to get along, the whole God deal, just what it meant to be alive during the Sixties. The young artists were ravenous to test their abilities; like the era’s emerging postmodern fiction writers, they were fluent in their chosen medium and knowledgeable about contemporary art and art history. They were also tripping balls.

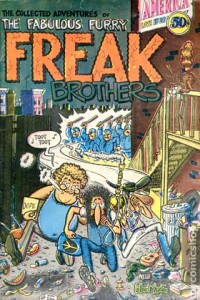

At the same time, an underground press was emerging in metropolitan centers and college towns. Papers like Chicago’s The Realist, New York’s East Village Other, the Los Angeles Free Press, and the San Francisco Oracle provided artists with sympathetic venues for their drawings. As their work spread, the definition of comics expanded until finally, in 1968, Crumb put out a full-length comic, Zap #1, that made him the genre’s first breakout star. Soon, he was drawing an album cover for Janis Joplin, and turning down the Rolling Stones’ request that he do one for them. Gilbert Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers — three brothers on the prowl for “weed, women, and whatever” — soon followed, as did others, published by a network of small presses selling the work in head shops, record stores, on the street, and by mail order.

In 1973, as the Vietnam War was ending and Sixties counterculture was winding down, the Supreme Court ruled, in Miller v. California, that local police could enforce community obscenity standards. Various municipalities took this as a green light to harass vendors, while post offices took it as license to confiscate parcels suspected of containing “obscene” material. Many head shops, frightened by the possibility of litigation, stopped stocking comix, but by then the underground-comix movement had been established. Cagey editors, distributors, writers, artists, and friends of friends provided contact info for each other; letters of mutual appreciation led to road trips during which everyone got baked and stayed up all night writing and drawing, then crashed in some back room. The scene congealed in San Francisco, with writers and illustrators contributing to one another’s books, creating crazy one-off titles together, sometimes by forwarding pages to one another and contributing a panel apiece per page. “All the magic of being in Paris for the post-Impressionist moment did feel,” said Art Spiegelman, “like being in San Francisco in the early Seventies.” It was during this era that Spiegelman published a three-page story, set in a concentration camp, that portrayed Jews as mice, Germans as cats, and Poles as pigs.

As the Eighties proceeded, the wall between high and low culture continued to crumble, courtesy of figures like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Madonna, as well as cultural phenomena like MTV. Superhero comics, too, began absorbing new influences. Frank Miller’s Daredevil and Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing were much darker and freer than their forerunners. Spiegelman’s mouse tales, inspired by his parents’ stories about life in a World War II concentration camp, continued to appear, mostly in Raw, a magazine he started with his wife, Françoise Mouly.

Underground comix were tackling subjects like estrangement from mainstream middle-class life and the dangerous reaches of censorship and the right wing, but probably the most interesting strain of work was personal, including Spiegelman’s work and Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor, which followed an outcast’s daily life in Cleveland. Raw encouraged and published a new generation of artists with a similarly intimate sensibility, among them Charles Burns, Daniel Clowes, and Chris Ware. Spiegelman’s work was featured as part of the Comics Show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1983. (“Some of the best American paintings of the late 1950’s and early 60s,” wrote New York Times art critic John Russell.)

The show served as both a review of the past and a glimpse of the future — for with the 1990s came legitimacy, acclaim, and popularity. Spiegelman received a special Pulitzer citation for the first volume of a two-volume MAUS collection in 1992. Crumb, meanwhile, became the subject of a feature documentary in 1994. Both men saw their work published routinely in The New Yorker, alongside other artists from the underground era, after Mouly became the magazine’s art director in 1993. Burns and Clowes each had graphic novels made into critically acclaimed and financially successful films, while Ware’s first graphic novel, Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid on Earth, won the American Book Award in 2001, and his most recent collection, Building Stories, was featured on the cover of the New York Times Book Review. With these successes, the newly respectable genre was renamed — dubbed “art comics” by critic Douglas Woulk — and granted its own canon.

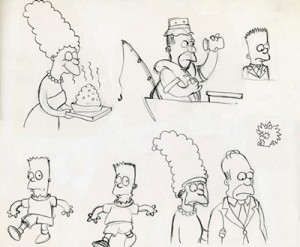

The genre’s artistic evolution alone would be enough to warrant being called a success story. But it also set in motion another major cultural development. In the late 1980s, television producer James Brooks began searching for animated shorts to run on a variety show being developed for British comedian Tracey Ullman on the new Fox Network. He’d had his eye on a cartoonist named Matt Groening, whose Life in Hell strip had been running in underground newspapers like the Los Angeles Reader and the Village Voice for more than ten years.[*] Brooks set up a meeting, and, standing outside Brooks’s office, Groening sketched out for him a family. Cue the iconic musical theme, Bart writing on the blackboard, and a show that tapped into the whimsy, informed sarcasm, and screwball mayhem of underground-comix culture.

[*] Groening has on occasion been prickly about being connected with comix, but as a Los Angeles Reader editor in the 1980s he was a key influence on the genre.

Still, though it provoked some family-values outcry initially, The Simpsons observed certain limits, in part because the show was on network television, and also because it was a big-tent show, designed to be popular among both children and adults. Archer, by contrast, is the underground fully realized — or as thoroughly realized as is possible on a corporate network. It is thoroughly for adults, and without compunctions or restraints, at least no restraints that I can see.

Works consulted

Mark James Estren, A History of Underground Comics (Ronin, 1993).

Patrick Rosenkranz, Rebel Vision: The Underground Comix Revolution (Fantagraphics, 2008).

James Danky and Denis Kitchen, Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix (Abrams ComicArts, 2009).

John Ortved, The Simpsons: An Unauthorized, Uncensored History (Faber and Faber, 2009).