In the June issue of Harper’s Magazine, Jay Kirk discusses Room 237, a documentary that screened recently during the Directors’ Fortnight at the Cannes Film Festival. The documentary focuses on the stunningly elaborate webs of interpretation that viewers have created to explain Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Writes Kirk:

Among the theories held by the fans interviewed in Room 237: (1) The Shining is really a veiled confession by Kubrick that he conspired with NASA to fake the footage of the Apollo 11 moon landing; (2) it’s really about the genocide of the Native Americans; (3) it’s a commentary on the Holocaust; (4) it’s not a horror story at all but actually a very slick vehicle for pulling off a series of seemingly pointless subliminal erotic gags.

Below is the unexpurgated transcript of a quotation from one of the film’s subjects, Geoffrey Cocks, in which he traces the evolution of his own theory.

I saw a number of Kubrick films before I had an academic interest in him, and then I went to see The Shining in 1980 and frankly I didn’t think that much of it. I thought the other Kubrick films that I’d seen were far superior but, as I thought about the film afterwards and even when I wasn’t thinking about it, there were things that bothered me about it. It seemed as if I had missed something and so I went back to see it again and I began to see patterns and details that I hadn’t noticed before, and so I kept watching the film again and again and again and since I’m trained as an historian and my special expertise is in the history of Germany, and Nazi Germany in particular, I became more and more convinced that there is in this film a deeply laid subtext that takes on the Holocaust.

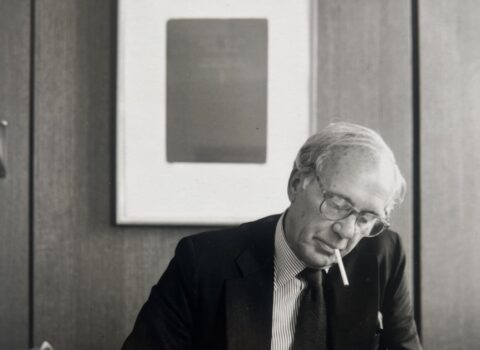

The typewriter from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Creative Commons photo by Rick Hall

I think it probably was the typewriter, which was a German brand — which might seem arbitrary, but by that time I knew enough about Kubrick [to know] that most anything in his films can’t be regarded as arbitrary. That anything — especially objects and colors and music and anything else — probably have some intentional as well as unintentional meaning to them. So that struck me. Why a German typewriter?

And in connection with that, I began to see the number 42 appear in the film, and for a German historian if you put the number 42 and a German typewriter together you get the Holocaust, because it was in 1942 that the Nazis made the decision to go ahead and exterminate all the Jews they could, and they did so in a highly mechanical, industrial, and bureaucratic way, and so the juxtaposition of the number 42 and the typewriter is really where it started for me in terms of the historical content of the film. Of course Adler in German means “eagle,” and [the] eagle of course is a symbol of Nazi Germany. It’s also a symbol of the United States. And Kubrick generally has re-coursed the eagles to symbolize state power.

Kubrick read Raul Hilberg’s The Destruction of the European Jews, and Hilberg’s major theme in there is that he focuses on the apparatus of killing and he emphasises how bureaucratic it was and how it was a matter of lists and typewriters. Spielberg picked that up in Schindler’s List of course, and the film begins with typewriters and lists and ends with a list of course, and so that informs, and I had a chance to talk to Raul Hilberg when he visited Albia College, and he [said] that he and Kubrick corresponded about this, and the fact that he had read it then in the 1970s when there was a big wave of interest in Hitler and the Holocaust and the Nazis, I think, just tells us that that typewriter, that German typewriter, which by the way changes color in the course of the film, which typewriters don’t generally do, is terribly, terribly important as a reference to that particular historical event.