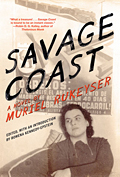

Savage Coast

Rowena Kennedy-Epstein on Muriel Rukeyser’s political and emotional vision

Muriel Rukeyser’s renown has surged in the years since her death, and with good reason. Much like the work of Adrienne Rich, her poetry became inseparable from the social upheaval she witnessed; indeed, some of her best-remembered writing grew directly out of crises like the Hawks Nest mining disaster in West Virginia and the trial of the Scottsboro Boys in Alabama. The bracing way she fused experiential narratives with activist politics gave voice to the social injustices of her day, and never failed to evoke hope that they would be overcome. Now, Feminist Press is releasing Savage Coast, a previously unpublished novel that Rukeyser began working on early in her career. The book, which was repeatedly rejected for publication, reveals the author’s literary voice in its early stages of formation, as she describes the start of the Spanish Civil War, which she witnessed while on assignment in Catalonia. I asked Rowena Kennedy-Epstein, the book’s editor, why Savage Coast was so poorly received and how it can help us better understand the Spanish Civil War, as well as Rukeyser’s artistic development.

1. Given that Rukeyser completed a manuscript of Savage Coast upon her return to New York from Spain in 1936, why did we have to wait until 2013 to see it published?

Rukeyser wrote Savage Coast with unusual speed and sent it to her publisher, Covici-Friede, before she had even completed it — half of one chapter remains in outline form. But her publishers hated it, and I say that with all the force of that word. A withering and sexist reader report, which Rukeyser kept and filed with the manuscript (she had a good sense of humor), called the novel “one of the worst stretches of narrative I have ever read,” with a heroine “made to seem too abnormal for us to respect what she sees, hears and feels.” In the spring of 1937 Pascal Covici reaffirmed that he wouldn’t publish it and encouraged her to start working on a new book of poems that would become her second collection, U.S. 1. She was twenty-three then, and one can only imagine the force of such a rejection, because it was so personal — she herself is the heroine who is “too abnormal.” But she kept working on the novel, editing it through to the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939. I’m not sure why or when she abandoned the manuscript entirely, but she revised it at least three times, and clearly she held onto it, only to have it eventually misfiled under “Miscellany” in the Library of Congress.

In many ways, the loss of Savage Coast is as interesting as its recovery, because it tells a story about how the conservative political, aesthetic, and gender dictates of the late 1930s were used to suppress certain kinds of texts and histories. Of course, the reasons for the novel’s rejection — its hybridization of prose, documentary, and poetry; its sexually liberated and autonomous heroine; its sympathetic portrayal of anarchism; its nuanced depiction of Spanish politics and protest; its critique of American capitalism — all make it interesting and exciting to read today.

2. Early on in the novel, one character remarks, “Hemingway doesn’t know beans about Spain.” How does Rukeyser’s take on the Spanish Civil War differ from literary narratives of the conflict that we might be more familiar with?

That line is so brilliant, so funny, in its pithy dismissal of Hemingway’s absurdly hyper-masculine fantasy of himself in Spain, but also because it is a commentary on the problematic nature of depicting another country, and a foreign war. Rukeyser is keenly aware of this throughout the novel, making Savage Coast an important counternarrative to canonical texts by Orwell, Hemingway, Auden, and others. The protagonist, Helen, never pretends to know more about Spanish politics than the Spaniards, never pretends to know the language, never mythologizes her role there, and records much of the actual political nuance of the country by listening to Catalans. Because of this, I think we are given a more realistic and interesting narrative of transnational solidarity, one that eschews didacticism and avoids the objectifying, tutoring (is there any other way to describe Orwell?), patronizing gaze so common to other texts by foreigners on the war.

What’s perhaps most different is the way in which women are depicted. That they are depicted at all, as fully realized characters, is already a striking counternarrative. Women are central to the book and its depictions of the war not just because it is narrated through a female protagonist, but because a kind of gender equity prevails among the Republican faction on the train. Helen and Olive both participate in the events and initiate action. Likewise, the Catalan women on the train are the first to narrate the complicated political dynamics of the war. Spanish women are shown talking about politics and participating in the resistance; they have friendships with men, with whom they debate and organize, while their friendships with other women are about politics, life, philosophy, and drinking, not about men. I can’t think of another text from this period where women are depicted in such a way.

3. Rukeyser uses a variety of newspaper clippings, poetic excerpts, and quotations from historical documents to introduce each chapter of Savage Coast. How does this emphasis on primary sources and other writers’ work inform the narrative space she herself is creating?

The first line spoken in the novel is “Look!” I think this is quite telling, because it is a very visual, filmic text, and for much of it Helen has trouble speaking and understanding Spanish and Catalan. Looking becomes a vital mode of gathering information. Looking is also essential to witnessing, documenting, and archiving, and Rukeyser’s inclusion of primary sources makes readers complicit in that act of witnessing, engaging them with histories that might otherwise be forgotten: the story of the People’s Olympiad, the narratives of those who died in the early days of the war.

Rukeyser famously wrote that “poetry can extend the document,” which is an apt description of the way she uses lyric interiority to build from and expand the meaning of the documents she includes. She makes connections between large public histories — the newspaper clipping, the speech form the French delegate, the list of the dead, the Olympic brochure — and her own personal history as it is being shaped inside the political moment.

Rukeyser’s use of literary quotation also enacts a kind of modernist revision of gender and genre by situating some of the most prominent male literary figures of her time in the book. She critiques, revises, and challenges those she quotes, as we see in the D. H. Lawrence scene, when Helen “claps the book shut” and begins her own narrative, or when Rukeyser uses Hart Crane’s poem “For The Marriage of Faustus and Helen” to open the sex scene between Helen and Hans, before reversing the traditional notions of male sexual authority and female virginal passivity depicted in the poem.

From Savage Coast:

They had expected city.

They saw nothing but street: a passage, impossibly long, bending from country road, where the barriers were far placed and long dashes could be made, to an avenue through glimpsed suburbs, and now this, which must be city, if the mind were free to look, but which seemed only street, broken by barricades at which the truck stopped, and the fringes could not be noticed, the faces, the piled chairs, corpses of horses. Then a spurt of speed, wind, and tight hands; and immediately a gap in the road, blind; after that second, recognized.

At such moments, the sides of the road may be discerned.

The sidewalks, the rows of houses, blocks of low-lying buildings.

And ahead? A wall.

The passengers drew in their breath as the men before it turned, the levers held in their hands, and the man with the gun came forward. For the levers chopped the street. The street was lifted to make this wall. The cobblestones were built high.

On the barricade, the red flag.

4. In your introduction, you describe the book as a “Bildungsroman of sorts” that follows Rukeyser’s “transformation from tourist and witness into activist and radical.” Given that the book grew out of Rukeyser’s own experience, what role do you think writing this novel played in the evolution of her poetic voice?

In many of Rukeyser’s texts on the Spanish Civil War, which she composed across forty years, she recounts the moment when she is given her “responsibility” by the organizer of the People’s Olympiad, who tells her and the other foreigners about to be evacuated, “You will carry to your own countries, some of them still oppressed and under fascism and military terror, to the working people of the world, the story of what you see now in Spain.”

“Your work,” Helen is told in the novel, “begins now.” Rukeyser describes this particular scene again and again in her career; the directive resonates throughout her life. So Savage Coast is a Bildungsroman in the narrative sense, as we encounter a young woman coming into maturity, but also in the biographical sense that it shows the young artist working through the forms and ideas that will shape her career. Like Lawrence in his early works, Rukeyser develops concerns here that she will return to again and again: desire, connection, mutability, seeking and remaking, and perhaps most especially challenging systems of power, oppression and silence.

In 1949, she begins her seminal Cold War text, The Life of Poetry, with the scene of her evacuation by boat from Barcelona. While on the boat, she is asked the almost apocryphal question, “And in all this — where is there a place for poetry?” Only a few years later, Auden pronounces, “Poetry makes nothing happen,” and the critical establishment agrees. Rukeyser writes against this assertion for the rest of her life, in every genre, returning often to her poetic and political awakening in Spain as “proof.” As if to challenge Auden, she writes in the Life of Poetry:

Poetry will not answer these needs. It is art: it imagines and makes, and gives you the imagining. Because you have imagined love, you have not loved; merely because you have imagined brotherhood, you have not made brotherhood. You may feel as though you had, but you have not. You are going to have to use that imagining as best you can, by building it into yourself, or you will be left with nothing but illusion.

Art is action, but it does not cause action: rather, it prepares us for thought.

Art is intellectual, but it does not cause thought: rather it prepares us for thought.

5. I’m always struck in Rukeyser’s poetry by her blending of the political and the emotional (I’m especially thinking of “Waiting for Icarus”). How did that emerging sensibility present itself in Savage Coast?

If anything, Savage Coast articulates clearly the deeply emotional experience of political change, for all the characters. Rukeyser seems to ask, how can politics not be emotional? At one point, for example, Helen begins to cry as she raises her fist in support of the Republic — “as if this were her dream that she was dreaming now.” She describes anarchist Spain as the place where she learns to say things “deeply felt”; where she is “born again”; and as the “end of confusion.”

Later, Rukeyser would write that the losses incurred in Spain “survive as lifetime sound.” Is there anything more personal, more emotional than the public experience of war? Inversely, is there anything more expansive, more moving, than the experience of awakening found in sexual liberation, gender equality, the fight for political justice? At the end of the novel, Helen says, “Only let me move, too, keep on pouring free,” underscoring how very emotional the fight for political justice is, because it’s also always about the struggle for one’s own autonomy and voice. Throughout her life, I think Rukeyser worked to articulate these interconnected experiences.

6. How did you assemble the finished manuscript? How much guidance did Rukeyser’s notes and edits provide?

6. How did you assemble the finished manuscript? How much guidance did Rukeyser’s notes and edits provide?

When I encountered the manuscript in the library for the first time, it was heavily edited and out of order. First, I pieced it back together using her diary entries, extra-poetic materials like maps and brochures, and her out-of-print essays on Spain. Luckily, I only had to put five days of traveling there back together! I then transcribed the entire original manuscript without her editorial changes as best I could, after which I went through and added her edits in layers according to their source.

It took nine months, but it let me better understand Rukeyser’s own editorial process. I was able to see how she changed the text in response to the ending of the war. The first line “everybody knows how that war ended” was added after 1939, as was the lyrical and solemn opening paragraph that situates the conflict as the opening of a new era of war and violence. So a sympathetic and nuanced portrayal of the Spanish Republic, perhaps originally intended to rally an aggressive response for the fight against fascism, became a more poignant and historical text about the loss of Spain and its revolutionary potential to fascism.

The difficulty of working on an unfinished text was my fear that, out of my own desire to make the novel readable, I would undo meanings that Rukeyser may have struggled to articulate. The few major editorial decisions that went against her final changes, which I talk about in the edition, were agonizing. Ultimately, the process was about trying to preserve the great beauty of the text, its strange contours and political insights, while giving the readers a way into what is, at times, a complicated aesthetic and political project.