Between seasons of Mad Men, when there are no new episodes to feed the Draper-obsessed populace, identifying the film and lit references in the show becomes a national pastime. But one particular reference has so far escaped notice. I mean the biggest one of them all: the title. At the beginning of the very first episode, a bit of text states that the phrase “mad men” was “a term coined in the late 1950s to describe the advertising executives of Madison Avenue. They coined it.”

Actually, they probably didn’t. After considerable digging, which I describe in this month’s Easy Chair column, I was unable to find anyone who could confirm that “mad men” was commonly used by people in the ad industry during the period described by the program. The phrase makes sense to our modern ear, because we think of advertising people today as zany free spirits, if not outright maniacs. But during the period when the show begins, the industry’s leading figures liked to think of themselves as rational — even scientific — men.

As far as I can tell, the phrase traces back to a single advertising exec of the era, one James Kelly of Ellington & Company, who moonlighted as a book reviewer and novelist. He died in 1993, so we can’t be absolutely sure, but the description of ad execs as “Madmen” appears to have been his personal invention. In a 1957 article for Saturday Review, Kelly wrote a round-up of what he called “Madman novels.” These books depicted the ad exec as an Ivy League graduate with a wife and a mistress; a figure who lives in constant fear of being fired for the slightest of reasons; and “a satisfying pro-consul to our dream-world of plenty.” Of the novels that Kelly discussed, only Frederic Wakeman’s The Hucksters and Sloan Wilson’s The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit are remembered today, and both have been referenced many times in Mad Men.

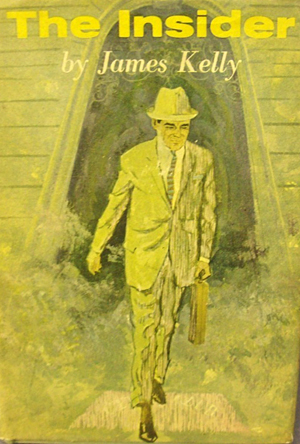

Kelly’s beef back in 1957 was that none of these novels gave us “the real Mad Avenue.” So the very next year, he took up this burden with an advertising novel of his own, a 384-page story of evil triumphant called The Insider. The book was well-reviewed, and Variety even thought it had “the makings of a brisk screen story.” Most importantly for our purposes: Kelly’s pet term for ad execs, “Madmen,” appears in the novel twice.

Is this the Urtext for the TV show? In some ways, it certainly appears to be. Kelly’s protagonist is not a good man who is disgusted and eventually corrupted by the industry — the traditional pattern of the advertising novel. Instead, Mort Noyes is a consummate heel, who makes his way by lying to everyone. The key to his success: he has married the daughter of one of the agency’s key clients, a patent-medicine tycoon who owns a troubled brand of toothpaste. (Note the parallel case of Pete Campbell in Mad Men, who married the daughter of a prominent Clearasil executive.) The agency also does advertising for the tycoon’s laxative brand, about which the admen joke constantly, just as they do in Mad Men — but it’s flagging toothpaste sales that frame the book’s anxious plot.

Of the two men who own the agency where Noyes labors, one is the son and weak-willed heir of the founder, like Roger Sterling; the other is a foreign-born accounting type. The office is of course fronted by a gorgeous executive secretary. Noyes drinks to excess and cheats outrageously on his blond wife, Grace, often with the agency’s female art director — who is liberated and “avant garde as hell,” like Don Draper’s mistress in Season 1. (Noyes and the art director get drunk listening to a recording of Dylan Thomas.)

The only real skill Noyes possesses — other than lying — is client presentation, which is also Don Draper’s strong suit in Mad Men. His colleagues, who despise him for his endless machinations, refer to him as “whoreboy Noyes,” just as the young Don calls himself “a whore child.” Noyes is supposed to be a cynical unbeliever: “No, as Mort clearly saw it, there was no one waiting. Smart people either lived each day as if it were their last, or they were half-dead already.” Draper says virtually the same thing in the Mad Men’s first episode: “I’m living like there’s no tomorrow, because there isn’t one.”

Numerous other details are shared by the long-forgotten novel and the celebrated TV show: a meal at Sardi’s, a divorce in Reno, the arrival of a third child just as a marriage collapses, a fistfight in the agency’s carefully decorated conference room. There is also a passage in The Insider that neatly expresses a central philosophical theme of Mad Men: “What was the phrase? — chameleon years,” Noyes thinks, pondering his knack for imitative empathy. “Two words which covered the story of his life since the war. Find what they’re drinking, and drink it. Find what they’re thinking, and think it. Find what they’re wanting, and want it.”

Then again, the similarities may mean nothing. Many of these tropes were such standard elements of the Madison Avenue myth — the suburban home, the infidelity, the references to whores — that they could probably be found in any account of the industry.

That’s why the differences between Mad Men and The Insider are actually more revealing than the similarities. The ad agency in the 1958 novel employs a female art director and a female promotions director, but at Sterling Cooper, the idea of women doing such work is supposed to have been almost completely beyond the comprehension of the male brain circa 1960. There are two Jewish characters in the novel, one of them an agency principal, whose role is to bring balance and a serious business demeanor to the lightweight atmosphere of the place. (“It would be Munich vs. Main Line, Heidelberg vs. Princeton . . . and, of course, Jew vs. Gentile.”) In Mad Men, which was created in a spirit of dizzy self-righteousness a half-century later, it is strongly hinted that preppy advertising agencies of that time would never hire Jews. (Although a young copywriter named Michael Ginsberg was added during the show’s fifth season, his “ethnic” accent and neurotic manner make him an obvious outlier.)

If there is anything really timeless about Mad Men, it is the feeling of fascinated horror that also enlivened The Insider more than fifty years ago — the prospect of clever people making a sumptuous living by lying to everyone: spouse, colleagues, client, and public. Mad men, indeed.