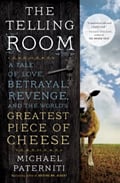

The Telling Room: A Tale of Love, Betrayal, Revenge, and the World’s Greatest Piece of Cheese

Mike Paterniti on the power of cheese, the pleasures of digression, and the War of the Roses method of book writing

Mike Paterniti. © Joanna Eldredge Morrissey

Mike Paterniti is a contributing editor for GQ. His first book, Driving Mr. Albert (Dial, 2001), was based on a feature he wrote for Harper’s Magazine in 1997; his second, The Telling Room, has just been released by Random House. In the new book, Paterniti tells of encountering a rare and delicious cheese while working at Zingerman’s deli in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Eventually he tracks down its maker, Ambrosio Molinos de las Heras, in the Spanish village of Guzmán, only to find that Ambrosio no longer creates the cheese. In the course of recounting Ambrosio’s tale, Paterniti dives deeply into Spain’s political history, the pleasures of craft, and the motives and methods of storytelling itself. I asked Paterniti six questions about his book:

1. How long did it take you to write The Telling Room, and why was it the work of so many years?

Full gestation took about ten years from start to finish, which sounds crazy, like my own War of the Roses. But there were a few mitigating factors in there: First, Ambrosio presented me with this fantastical story — about how he’d had his family cheese stolen, about how he was plotting to kill his best friend — and so I found myself trying to sort it all out while waiting to see what would happen with the real or imaginary murder plot. At some point, Ambrosio stopped talking about the cheese — it depressed him too much — but was more than willing to take me deep into his world, so we fell into this delightful stalemate, where as part of my research, I soaked up all there was of this little Spanish village and its stories. I spent hours in the telling room, listening to tales, drinking delicious homemade red wine. If I’d seen the book as a Slow Food tale gone awry, then this was Slow Reporting, and Slow Living. Besides any chance to add time to a story, for me at least, only deepens and complicates it. And that’s a good thing.

2. How do you describe a man like Ambrosio?

Ambrosio is one of those rare, elemental, hulking forces of nature you meet maybe once in a lifetime. Firstly, he’s a great, bawdy storyteller, very Falstaffian, and when he’s sitting in his telling room, unspooling a tale, it can last an entire afternoon, with these great asides and digressions, historical footnotes and factoids. But also, I’ve never met anyone as grounded in a place as he is in this little Castilian village of Guzmán. It’s very un-American actually, this groundedness, this conversation with the ghosts of the past and this code of honor that he lives by. Everything that he stands for — and all the love for Castile that he has — all of it he poured into this cheese, Páramo de Guzmán. And, of course, one of his life’s great trials began when he lost it. How he was going to survive, and reanimate himself, became a big part of the book.

3. An oral storyteller once advised me that a tale should begin with the teller swearing that the story she’s about to tell is entirely true, even as the audience knows deep down that they’ll be hearing something spun. You struggle throughout the book to navigate your position toward the stories you hear, in part because you feel a strong desire to revere the teller, his tale, and the object — the cheese — that attracted you in the first place. Why were you so drawn in by Ambrosio’s account of Páramo de Guzmán?

Because, sitting in the telling room, with Ambrosio’s voice echoing, there was no way, at first, not to believe it. Of course, I deeply wanted to believe in the legend, the fairy tale of it, the once-upon-a-time-there-was-this-cheese impossibility of it. I mean the facts were fairy tale-ish to begin with. A man recovers an old family recipe for this Manchego-like cheese, buys some sheep that graze on the Meseta outside of his home village, and with the sheep milk, he resurrects the cheese again, in a stable across from the house where he was born . . . and his father before him . . . and his father before that. When people tried this cheese, they had memories of being young again, when every house made its own cheese. It brought them back to their mother’s kitchen, with their mothers alive again. And then the cheese was passed along, from hand to hand, until it reached Madrid and then London, until Fidel Castro tried it and wanted to buy all of Ambrosio’s stock, until royal families and presidents, movie stars and singers like Julio Iglesias were served the cheese, and loved it, too.

I spend so much time in my day job having to exercise this skepticism that I found myself following this particular plotline like a child listening to a story, wondering what would come next, not whether it was true or not — at least at first.

4. You ultimately had to make a decision about whether to directly intervene in the tale of betrayal at the heart of the book. How comfortable were you with the extent to which you became part of Ambrosio’s story?

Oh, not comfortable at all! I spoke to my editor and reporter friends about how far I should go in mediating the feud, because suddenly I was being asked to carry messages. Even going to Julián — Ambrosio’s former best friend and business partner — in the first place felt like a betrayal of Ambrosio. By this time, he’d taken me fully into his world. He treated me and my family like family, with that great Castilian generosity. And then here I was, going off to talk to his archenemy and bugaboo. In fact, that’s partly what made the writing take so long, too. The way I dragged my feet in the end, to avoid these last showdowns.

5. The book’s footnotes are almost a story in themselves — I’m thinking of one multilayered riff on Pringles, in particular. In framing your tale, how did you make peace with digression?

There came a point in the evolution of bookwriting centuries ago when footnotes fell out of favor, primarily because they were costly in the printing process. I love what Noel Coward has to say about them, something like, “Reading a footnote is like having to answer the front door while making love.” But eighteenth-century books were chock-full of such notes, as were the oral stories told in the telling rooms of Guzmán. Some people might struggle at first with them, but then my thought is that you don’t always have to answer the front door while making love. There’s an optional quality to them. I just wanted the book to stylistically mimic the stories and their exaggerations. But most importantly, some of the deepest truths were revealed to me in the asides and footnotes while in that village, in the marginalia of what people were saying, so I wanted the same for this book.

6. Near the end of the book, you raise your fear of the effects of the “digital avant garde” and quote Walter Benjamin, who in 1936 said, “The art of storytelling is coming to an end.” Do we need a Slow Storytelling movement?

6. Near the end of the book, you raise your fear of the effects of the “digital avant garde” and quote Walter Benjamin, who in 1936 said, “The art of storytelling is coming to an end.” Do we need a Slow Storytelling movement?

I think that’s perfectly put — and I would agree. I love the resurgence of storytelling in great series like The Moth, but I also love stories that aren’t crafted and rehearsed and canned at ten or fifteen minutes. I mean, our life doesn’t include much room for the four-hour story, unless we’re on a trip, but there are unbelievable payoffs and elations, humor and connectedness that comes from just that: a table with a porron of homemade wine and chorizo on it, people huddled together, and the storyteller taking that first breath to speak. The anticipation, that childlike joy and wonderment at what might happen next, that’s why we tell stories in the first place.