The Bloom Comes Off the Georgian Rose

In the aftermath of Georgia’s presidential elections, questions emerge about Mikhail Saakashvili’s support for jihadist operations in southern Russia, and about what the United States knew

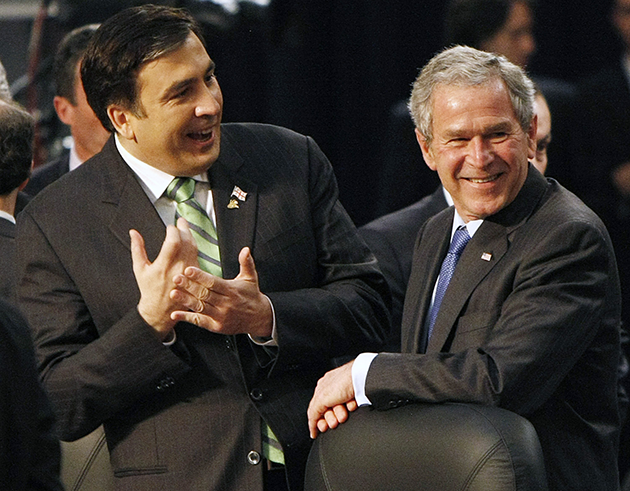

U.S. president George W. Bush talks with Georgian president Mikhail Saakashvili prior to a NATO summit meeting on Afghanistan in Bucharest, Romania, Thursday, April 3, 2008. © AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

Sunday’s presidential election in Georgia almost certainly marked the formal end of the political career of Mikhail “Misha” Saakashvili, the golden boy of the Rose Revolution and former Washington pet. As he exits the palace, with an indictment for crimes allegedly committed during his eight-year reign (including the murder of a political opponent) in imminent prospect, Saakashvili leaves many questions unanswered. Among them are his precise role in fomenting jihadist activity in the Russian republics to his north, and the extent of Washington’s knowledge of same. As we shall see, ongoing inquiries into a shootout in a remote Georgian gorge last August suggest some of the answers.

The 2003 Rose Revolution that brought Saakashvili to power was the first of the “color” movements combining mass protests with adroit marketing strategies that became ubiquitous a decade ago. As with Ukraine 2004 (Orange), Kyrgyzstan 2005 (Tulip), and Lebanon 2005 (Cedar), the Georgian movement was fuelled by popular outrage at a corrupt and politically bankrupt regime — that of President Eduard Shevardnadze. Back in Washington, the Bush Administration did not entirely thrill to these events. It had enjoyed amiable relations with Shevardnadze, who among other services had been obligingly rounding up bodies for the burgeoning U.S. rendition program.

Saakashvili accordingly signed up Randy Scheunemann, a former Republican senate staffer supremely wired in neo-con circles, to improve his standing in Washington. By the time Saakashvili ran for president in 2004, the Bush Administration had cast aside its doubts and was anxious only that the election not appear to be a Soviet-style sweep. The late Greg Stevens, an accomplished elections manager from the powerful Republican firm of Barbour, Jones, Griffiths — veteran of twenty-six elections from Costa Rica to Korea; victor in eighteen — was accordingly dispatched to give the opposition a lift. “I love Georgia,” he told friends at a London dinner party on completion of his mission in reference to the country’s political culture. “It’s so cheap.”

Post-election, Misha did not disappoint his new friends in Washington, especially those in the Office of the Vice President. Apart from eagerly promoting Georgia’s candidacy to join NATO and dispatching a battalion of troops to Afghanistan, Saakashvili was happy to host an ever-growing contingent of U.S. intelligence teams from both the CIA and the Joint Special Operations Command. Georgia was an ideal home away from home for American spooks, thanks to its adjacency to Iran (no visa is required for Iranians to travel there) and to Russia’s perpetually fraught Caucasus region. In no time at all, according to a former CIA official, Georgian mountaintops began sprouting antennae-crowned NSA listening posts. Alongside them loomed Israeli radars, purchased by the Georgian government as part of a booming arms trade between Tel Aviv and Tbilisi.

Unfortunately, as with other U.S. clients before him (think Anwar Sadat), these new relationships began to go to Misha’s head. Although he was less popular in Europe — Angela Merkel was reportedly disgusted by the details of his partying lifestyle that she encountered in his German intelligence dossier — the telegenic Georgian leader luxuriated in his Washington contacts, which spanned both sides of the aisle and included his close friend Richard Holbroke.

None of this went down well in Moscow, of course. Quite apart from the threat of U.S. espionage, the Russian government was facing ongoing insurgencies in the Caucasian republics, which were being resupplied by jihadist stalwarts traversing through Georgia seemingly unchecked by Saakashivili’s government. It would not have taken too great a leap of Putin’s imagination to assume that such activity had Washington’s blessing — after all, Al Qaeda was born out of the U.S. contribution to the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan.

By 2008, Saakashvili’s hubris led him to openly challenge the Russians, boasting of how “my tanks” and “my radars” were fully capable of confronting the Bear. “He actually thought he could win a war!” a Georgian politician told me. Washington itself was split. Bush could see that a war between Russia and a putative NATO ally might lead to a bad result, and he was concerned enough that in 2008, at a NATO summit in Bucharest, he took Saakashvili aside in the company of national security adviser Stephen Hadley and told him not to provoke Russia. Sources privy to the meeting tell me that Bush warned the Georgian leader that if he persisted, “The U.S. would not start World War Three on his behalf.”

This was not the only signal Saakashvili was getting from imperial headquarters, however. According to a former U.S. national-security official who has closely followed the relationship between Georgia and the United States for many years, Dick Cheney saw much to be gained in a Russo-Georgian conflict. “At best Georgia would win, in which case Russia would fall apart,” the official told me, “and at worst the spectacle of Russia crushing little Georgia would reinforce Russia’s reputation as the cruel Goliath. So Cheney was telling Misha, ‘We have your back.’ ”

To add to the mixed messaging, secretary of state Condoleezza Rice arrived in Tbilisi on July 9, 2008. While she reportedly reiterated Bush’s warning to Saakashvili in private, in public she proclaimed defiant support for Georgia in the face of Russian pressure, emphasizing the friendship between the two countries, which was precisely what Saakashvili wanted to hear. “It was her April Glaspie moment,” said the former official quoted above, referring to the hapless U.S. ambassador who led Saddam Hussein to believe it was okay for Iraq to invade Kuwait.

Whatever finally stimulated Saakashvili to open hostilities by bombarding the disputed Russian territory of South Ossetia, Russia’s response was swift and effective, beginning with the demolition of all those expensive NSA listening posts. “They destroyed about a billion dollars’ worth of equipment in the first few hours,” a former CIA official told me. “That was a high priority for them.” Meanwhile, Russian forces advanced deep into Georgian territory, crushing any resistance they encountered. Amazingly, this came as a surprise to Saakashvili and his coterie. As the deputy defense minister, Batu Kutelia, told the Financial Times shortly after the ceasefire, Georgia had made the decision to commence hostilities without anticipating that the Russians would respond in force. “Unfortunately, we attached a low priority to this,” he told the reporter, sitting at a desk with the flags of Georgia and NATO (to which Georgia did not belong) crossed behind him. “We did not prepare for this kind of eventuality.”

Humbled, but not much, Saakashvili pledged anew his allegiance to Uncle Sam, welcoming more military and intelligence liaisons while offering to double the number of unfortunate Georgian soldiers dispatched to the wastes of Afghanistan’s Helmand province. Meanwhile, he appeared unconscious of the rising discontent among a populace infuriated by his cronies’ land grabs for extravagant casino developments, as well as his draconian crime-fighting policies. Following the path blazed by Rudy Giuliani, he imposed a “zero tolerance” approach, in which charges of even minor crimes were swiftly followed by heavy fines or prison sentences with an extra larding of police torture. Faced with the prospect of leaving power once his two-term limit was up at the end of 2013, he took a leaf from Putin’s book and adjusted the constitution to transfer executive power from the presidency to the prime ministership, which he expected would be his after his party won the 2012 elections.

Nemesis came along in the form of Bidzina Ivanishvili, a billionaire who had gained his fortune in the heady days of 1990s Russia before returning to roost in a glass mansion perched high above Tbilisi. Saakashvili seemed to be coasting confidently toward victory in the parliamentary elections when the oligarch came forward to contest the poll at the head of a new party he was financing, called Georgian Dream. Following the tried and true practices of modern democracy, both sides armored up with Washington consultants and pollsters. Saakashvili had already retained Tony Podesta in an effort to forge links with the Obama Administration — Podesta’s firm being generally acknowledged as the most efficacious route to the current White House, and to the ultimate prize of a photo-op with the president himself. (“A picture of an Oval Office handshake can be worth a million dollars to a client, and Podesta is really good at getting those,” a lobbyist with another firm told me enviously.) The challenger hired the formidable firm of Patton Boggs. During the run-up to the vote, the forward squads of these warring consultancies crowded into Tbilisi’s Radisson Hotel. “I came downstairs for breakfast on election day and thought I was on K Street,” Steve Cohen, a Democratic congressman present as a neutral election observer, told me later.

While Saakashvili sought to portray his opponent as a Kremlin pawn, Ivanishvili’s team sweated in fear that Washington, which clearly viewed a Saakashvili victory as a not-unwelcome inevitability, would overtly express support for him. (Whatever their feelings about the incumbent, the Georgian people liked the idea of being friends with the United States.) In an effort to intimate that Ivanishvili had close American connections, his team hired a U.S. security contractor to supply former Special Forces members to stand conspicuously around him at rallies.

Two weeks before the vote, a video shot by a whistle-blowing police officer mysteriously materialized. The footage showed graphic scenes of torture by Saakashvili’s law-enforcement apparatus, up to and including the sodomy of a screaming prisoner with wooden batons. Voters were horrified, and on October 1, 2012, Ivanishvili’s party won a decisive victory, much to the surprise of Saakashvili’s costly retinue of Washington consultants.

Almost unnoticed amid the froth and fury of the campaign was a strange incident at Lopota gorge, in a remote corner of the country near the border with the Russian republic of Dagestan. According to Georgia’s interior ministry, three troops were killed in a clash with a “squad of saboteurs,” following an operation to “free hostages.” The ministry announced that eleven members of the armed group had been “liquidated.” Pro-government TV stations suggested that the group had infiltrated Georgia from Dagestan.

In April of this year, however, Ucha Nanuashvili, Georgia’s public defender — an official analogous to New York’s public advocate (currently Bill De Blasio), who had been appointed by the incoming Ivanishvili government — suggested that something very different had occurred. According to Nanuashvili, the armed group had in fact been formed, armed, and trained by the interior ministry itself. The ministry, a powerful force under the previous government, had recruited Chechens living in Georgia for the group, with the promise that they would be spirited across the border to join the fight against Russia in the North Caucasus. The soldiers killed in the attack, the public defender alleged, had in fact been escorting the group to the border when they were attacked by other Georgian government forces.

On October 22, Nanuashvili followed up, announcing the formation of a high-level commission to further investigate the incident. Meanwhile Tbilisi has been rife with rumor, including one suggestion that Saakashvili was intent on provoking either a violent Russian response or giving himself an excuse for a military crackdown under the guise of combating terrorism, thereby justifying a suspension of the vote. The public defender’s investigation so far, detailed in his 600-page report, buttresses longstanding Russian claims of ongoing support by Saakashvili for jihadist operations.

So, big questions remain: Was Lopota just one of a series of such operations? And if so, did the various U.S. intelligence contingents in the country know about, or even bless, these operations? Vladimir Putin has his own suspicions, which may help explain why he has been putting spokes in Obama’s wheels in Syria and elsewhere.