The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem

Jeremy Dauber on the remarkable life and afterlife of the man who created Tevye the Dairyman

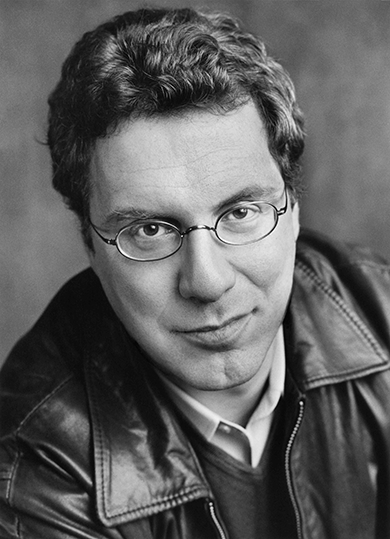

Jeremy Dauber is the Atran Professor of Yiddish Language, Literature, and Culture and Director of the Institute for Israel and Jewish Studies at Columbia University. He is also a friend. Whenever we meet, I’m awed by his luck — he crosses Broadway without taking his face out of whatever book he’s reading — and by his wisdom — he knows everything there is to know about Yiddish literature of the turn of the century, and about sci-fi literature of the turn of the millennium. His two previous books have ominous titles — Antonio’s Devils, and In the Demon’s Bedroom — but perhaps even more ominous subtitles: Writers of the Jewish Enlightenment and the Birth of Modern Hebrew and Yiddish Literature; and Yiddish Literature and the Early Modern, respectively. The concealed connecting plot of those books — how Eastern European Jewry codified itself and reconciled its folkways with Western European concepts of narrative — finds its hero in his new The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem: The Remarkable Life and Afterlife of the Man Who Created Tevye (Schocken Books), the first extended biography of the great patriarch of Yiddish lit. Jews have always worked as roving peddlers, and today is no different — it’s just easier to be in touch. Because Jeremy was off on a reading tour, I put six questions to him via email:

1. Sholem Aleichem — as your subtitle says, he’s the man who created Tevye the Dairyman, who later gained fame in Bock/Harnick/Stein’s Fiddler on the Roof. I was struck by that — the marketing reliance on people’s recognition of a fictional character, but not of an author. This is surely a Yiddish joke. So, for an audience that might not have “If I Were A Rich Man” stuck in their heads, who was Tevye’s creator?

So Sholem Aleichem (real name: Sholem Rabinovitch; the former is a pen name taken from the Hebrew/Yiddish phrase meaning “Peace be upon you” but idiomatically coming across like “How do you do”) was the modern Jewish writer par excellence: by which I mean that he encompassed the multitudes of Jewish modernity in one person. All the movements of modern Jewish times: theological (from ritual observance to cultural attachment), geographical (from Eastern Europe to America), ideological (embracing, at various times, emancipation movements, Zionism, socialism, even Americanism, if that’s an ideology) — he not only experienced them all, but he translated them into funny, touching, bracing, and more than occasionally biting stories that helped his community think about — and deal with — a world in the throes of a fundamental transformation.

2. One recent and I think pernicious trend in biography is the taking of what I — someone who wears very heavy glasses, but still finds most biographies unreadable — call the “lens approach”: So-and-So through the lens of politics, or gender, or race. But your book doesn’t do that — doesn’t require that — it has the pleasure, and difficulty, of a prismatic subject. Sholem Aleichem was a socialist, or wasn’t, a Zionist, or wasn’t — an American and European both, and everywhere a Jew. To mix metaphors, was this man of the theater just a series of masks, an actor? Was this man who often made himself a character in his own stories something of a character in his own life?

On the one hand, Sholem Aleichem (his pen name became the one he used not only in his stories, but in much of his personal life) was well aware that he lived a life of performances: he once wrote his family a letter about a particularly ridiculous experience he and his wife had encountered on the road, and then told them to make sure the letter was preserved so that it could make another appearance as literature. And a good number of his stories feature a character named Sholem Aleichem who readers are supposed to both identify and not identify with the real author. (Tevye, for example, exists in the original story version as a monologist whose audience consists of “Mr. Sholem Aleichem.”) On the other hand, he was a creature of what seems to have been genuine enthusiasms, without apparent artifice: when he became enraptured with the socialist revolutionary movements leading up to the First Russian Revolution, for example, or when he dreamed of the possibilities that Zionism offered the Jewish people, he seemed, at times, to be wholly caught up in the moment.

I think both are genuine sides of his personality: a man who suddenly rose from rags to riches and then landed back in rags again would be capable of appreciating the possibility of becoming something else. Although there was a voice inside his head — a Jewish voice, I think, but also an actor’s voice — that said that even though the mask could become the face, there was always another mask coming along, right around the corner . . . which held the genuine prospect of becoming a face of its own.

3. Sholem Aleichem was a master of a language not many people read anymore — a language still in use by the religious and the academic, mostly, neither of whom (sorry) are known for having the best ears for fiction. How to explain the linguistic ebullience to someone who doesn’t have Yiddish? What’s lost in translation, besides everything?

I think the biggest loss is actually something that combines the two communities you mentioned in the question — the way that Yiddish, as a Jewish language, bears within it allusions and resonances to millennia of Jewish history and culture, ranging back to the Bible (and Sholem Aleichem loved the Bible very dearly). Sholem Aleichem’s Yiddish, capacious but consciously not recondite, alerts the reader to the ways in which his stories have natural connections to the archetypes of Jewish life and fate in a way that English can’t accommodate without either copiously footnoting the text or studding it with archaisms. There are other losses — probably the other biggest one is the sense of regional and sociological diversity on display through different dialects, phrasings, etc., which really showed the remarkable variety of a Yiddishland we now tend to view, if at all, as one undifferentiated mass. But the first loss I mentioned resonates more largely with me, perhaps because my first book was on allusion in Hebrew and Yiddish literature.

4. Your book is very revealing about Sholem Aleichem’s relationship to Russia, and to Russian. Indeed, he also wrote in that language. What can you tell us about the relationship between his Yiddish and Russian works? Were they intended for different audiences?

Sholem Aleichem had a deep, and deeply complex, relationship with Russia, and with Russian culture. On the one hand, he loved Russia — he even hoped his body would be reinterred there after the hostilities of the Great War, which had forced him to cross the Atlantic for the final time, had come to an end. And his deep and abiding familiarity with and love for Russian literature — Chekhov, Gogol, Gorky, Turgenev, and many others — manifested itself not only in his writing but in his efforts to reach out to those writers to collaborate on literary projects and to have his own works appear in that language.

That said, he was increasingly aware, particularly after the failed revolution of 1905 and the Beilis blood libel trial, that Russia was no home, and might never be one, for Jews. And this was, I think, a real personal tragedy: it was, more than anywhere else, his home. (I’m using the word “Russia” a little broadly: technically speaking, he was born in the Ukraine, but the point is a general one.)

5. Contemporary fiction by American Jews has, generally speaking, abandoned the sex of Bellow and Roth — and neglected the politics of Israel–Palestine — in favor of exploring Jewry’s European inheritance. Sholem Aleichem largely sentimentalized the shtetl — the small Jewish enclave beset by illness, poverty, and pogrom — in a way not typically found in other Yiddish writers you’ve translated, such as the chilling, masterful Lamed Shapiro. What do you make of the dissonance between Sholem Aleichem’s depictions and the reality of the coeval European Jewish situation? And what do you make of today’s American Jewish writers returning to the shtetl in somewhat the same way?

One of the most interesting things about the way Sholem Aleichem’s work has fared over the century or so since its release is that many of its critics and readers, perhaps influenced by the author’s own large-hearted statements about his love for his people and his own elegies to the vanishing traditional community, have underemphasized (and sometimes plain overlooked) the satirical and angry edge in much of his work, an edge which targets the Jewish community as well as the outside forces that had such animus for it in his lifetime (and beyond). Many of Sholem Aleichem’s Kasrilevke stories, for example — his tales from an Everyshtetl — while often held up as examples of a sentimentalized shtetl, are, when you look at them closely, also satires of the way his community’s propensity for argument, mockery, and cynical or ironic resignation can get in the way of positive or progressive action.

Let me be clear: this is not to say that Sholem Aleichem was a self-hating Jew — nothing could be further from the truth — or that he had any illusions about where the deep problems of Jewish life in Russia lay. (His stories around the pogroms in Kishinev and the Beilis blood-libel trial make that perfectly evident.) But he was more than just the simple sentimentalist some of the post-war readers make him out to be, and this is part of the story of his afterlife. I would say, though, that Sholem Aleichem — a century ago — felt that acculturation, urbanization, emigration, and modernity was marking the loss of a certain kind of traditional Jewish life, and, almost certainly more importantly to him, a kind of engagement with Jewish history and knowledge that was a close analogue to authenticity for him. And I think that many of today’s Jewish writers, a good number of whom are very knowledgeable and deeply immersed in Jewish history and knowledge, and who suffer the same concerns about their reading audience, therefore adopt the same preoccupations, settings, and proxies for authenticity.

6. Sholem Aleichem was a formidably prolific writer, but one book he could never finish was his autobiography — which cuts off in his early twenties (which is the age at which I feel like I stopped living myself). I suspect he never completed the book because the responsibility was too weighty — at the end of his life he was immensely respected and beloved, and so had to make the Life equal the Work, at the risk of detracting from his legacy. I’m wondering if you felt similar pressures, because it frequently seems like your book seeks to redress the fading of his literary popularity and influence as a proxy argument for the continued relevance of Yiddish culture in toto. Is there a grander project at work, then? Is there a future for Sholem Aleichem’s sensibility?

6. Sholem Aleichem was a formidably prolific writer, but one book he could never finish was his autobiography — which cuts off in his early twenties (which is the age at which I feel like I stopped living myself). I suspect he never completed the book because the responsibility was too weighty — at the end of his life he was immensely respected and beloved, and so had to make the Life equal the Work, at the risk of detracting from his legacy. I’m wondering if you felt similar pressures, because it frequently seems like your book seeks to redress the fading of his literary popularity and influence as a proxy argument for the continued relevance of Yiddish culture in toto. Is there a grander project at work, then? Is there a future for Sholem Aleichem’s sensibility?

Sholem Aleichem started writing his autobiography then stopped many times late in his life, and the reasons he gave for doing so ring true to me: he seemed to think of his autobiography as a sign that his life was behind him, that his main work was retelling, rather than telling. That’s why he usually turned to it around periods of illness, and abandoned it when he felt better. He certainly also felt that need to manage his reputation. It is interesting, though, how a life as viewed from the inside fails to accord with the outside perspective: though revered, he was dying in America as a war refugee, unable to get top dollar from most of the New York Yiddish newspapers, feeling that Yiddish literary trends had passed him by, concerned about his bills, a failure in the world of the theater, a literary life in English at best a promising possibility; you can see how he might have thought that his great dreams — of becoming an immortal like his idols Tolstoy and Dickens, of providing limitlessly for his heirs — had eluded him.

A hundred years later, his works (albeit in adapted form) are world-famous; his name is one of the few to have survived the cataclysm that swallowed up almost all of Yiddish culture, and he stands, in a way much different than Singer, his only other possible competitor in this respect, as someone whose legacy speaks to the possibility that great Yiddish literature, like all great literature, can be universal.

As a biographer, you want to be responsible to the legacy of a writer whose talents transcended the particular, and who, as an individual, reflected an entire Jewish period and world in miniature. The fact that there has been such interest in the book, and that such a variety of institutions and individuals has wanted to talk about it, suggests that Sholem Aleichem’s story still resonates in contemporary Jewish culture. I think it may even be indispensable.