My father is a retired engineer who worked for a defense-industry giant for fifty years — from 1936, when they were already selling sleek bombers to Chile and Bolivia, until 1986, when they were building the ICBM that Reagan named the Peacekeeper. It was from him that I first absorbed the fact that “defense” is a business, with products to be created and sold just like any other. When I was a Sputnik-driven kid in the 1950s, we talked about rockets all the time and even built a few working models, but in our mutual old age we rarely touch the subject anymore. Medical issues concern us now. Specifically, his teeth are loose and his pension plan does not include dental.

I can sympathize, because though I teach at a university whose name is synonymous around the world with medical science and public health, I don’t have dental insurance, either. When the dentist recommends a five-figure fix for periodontitis, all I can afford to do is smile back at him with the stubs that are still rooted in my head. So my father and I now compare notes on something worth serious attention: how to make your own teeth.

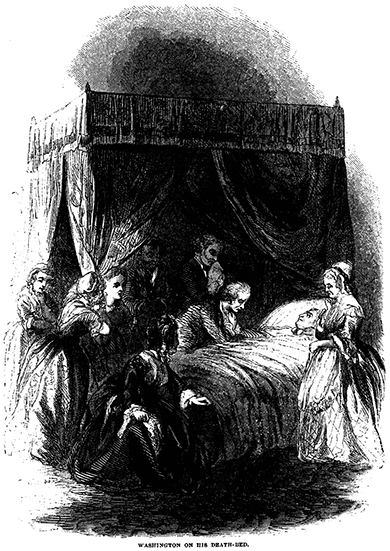

Happily, at ninety-five he is in remarkable health and has lost only one tooth, toward the back, which a professional would identify as the mandibular left first bicuspid. I’m also pretty fit at sixty-five, with no gaps yet but a molar or two that are shaky to the touch and will probably go within a few years. We are therefore interested in single false teeth, not dentures à la George Washington — at least not yet. Like many people, we were misinformed about Washington’s famous choppers having been crafted from wood. He actually owned a set made of iron, and other sets, devised near the end of his life, made from hippopotamus ivory and extracted human teeth. Washington’s dentist, a New Yorker named John Greenwood, would pay skid-row denizens a pound and sixpence each for their teeth, which he then pulled out and incorporated into metal plates hammered to conform to the surfaces of his patients’ mouths. In a year or so the teeth rotted and turned brown, but Washington apparently preferred the natural look to the gold, mother-of-pearl, or agate teeth worn by other gentlemen of the day.

The point is that false teeth can be made simply and well with enough practice, as the Etruscan artists who made splendid teeth out of ivory and gold bridgework knew 2,700 years ago. I live on a farm and have assembled a good machine shop over the years, so we possessed all the tools we needed to fabricate an item of this kind. Our first dry run involved cows’ teeth, which Washington also tried early on, that were supplied to us by a dairy farmer down the road (he lacked dental insurance, too, and comprehended our ambition immediately). We bought some 0.5-millimeter copper leaf, filed down the bovine teeth to human size, and found that we could wire them to the plates quite sturdily. It was obvious, however, that though the mounted teeth might pass cosmetic muster, they could not withstand the lateral or compressive forces of actual chewing. Eighteenth-century denture-wearers learned this quickly, too, and either took out their accessories when they dined or risked having them shoot out of their mouths, propelled by the steel springs that hitched upper to lower plates.

Ivory being contraband nowadays, and teeth from human cadavers — another choice in Washington’s era — being out of the question even with my university-hospital connections, we decided to try hard-baked porcelain. These so-called “mineral paste” teeth had been perfected by French and Italian dentists in the early nineteenth century — too late for the first president, who died at Mount Vernon in 1799, possibly of diphtheria, or maybe of a bad throat infection exacerbated by his rancid dentures. In 1822, Washington’s portraitist, Charles Peale, helped make ends meet in Philadelphia by baking and selling mineral teeth, which became a sizable industry there by midcentury. Charles Goodyear provided the real breakthrough in 1839 with vulcanized rubber, which provided a strong base for false teeth and could be closely molded to the mouth.

My father and I lost a lot of time trying to duplicate these old methods. We bought a small potter’s oven and a porcelain mix at a craft shop. We learned that heating a slab of rubber sliced from an old tire is noxious business. About the third time around, we gazed at each other and remembered what century we were in. I went upstairs to my office over the shop and hit the internet, quickly finding fast and cheap products for making theatrical false teeth, à la Nosferatu, that could be modified for real use.

First, you make an impression of your bite with a soft casting material called alginate. Then you fill the cast with Moldano, a dental plaster that will harden like porcelain. Using a scalpel and a plaster rasp you fix any little defects, and now you have a perfect model of your existing teeth. The next step is to sculpt in wax or clay the tooth (or teeth) that will fill whatever’s missing. You then make a mold of it with the alginate and flood the mold with dental acrylic, which comes in powders of various colors that mix with a solvent. By pressing the Moldano cast into the mold before the goop completely sets, you get a solid replacement tooth bordered by a thin set of “glove” teeth that fit over your abutting ones. Polishing the surface with a sanding tool and ordinary toothpaste finishes the job. All that’s left is to glue them on with denture cream. They’re so economical, at just a few dollars a rig, that you could make thousands of spare sets for the price of a single set of professional dentures.

So far we haven’t noticed a downside to our scheme. As long as we do it just for ourselves, we’re not breaking state laws against practicing without a license. My father is no longer embarrassed to smile a big smile, and I’m no more or less worried about periodontitis than about a million other medical bad dreams. Do I recommend this for everybody? Sure. I mean, of course not, but there’s a satisfying lesson in it somewhere about business, technology, and fending for yourself with so many dafties in Congress.