The people recognise themselves in their commodities; they find their soul in their automobile, hi-fi set, split-level home, kitchen equipment. —Herbert Marcuse

“Kevin’s Delivery” is a thirty-second television commercial for the painkiller Aleve, in which the voice-over tells us “This is Kevin. To prove to you that Aleve is the better choice for him, Kevin has given up Aleve for one day.” He has been asked to go back to taking Tylenol as he makes his UPS-type delivery rounds. During this introduction Kevin is coming down the stairs in his house at the start of the day, rubbing his knee. In his kitchen, a hand from nowhere gives him a small bottle of Tylenol. Already skeptical, even a little peeved, Kevin asks, “That’s today?”

He goes about his deliveries. At one point, holding his hand truck, he pauses to say to the camera, “That was okay, but after lunch my knee started hurting again, and now I gotta take more pills.” Then there’s a cut to Kevin sitting on the back of his truck, ostensibly later in the day, and he says, “Yup! Another pill stop. Can I get my Aleve back yet?” Finally, we see Kevin at the end of the day holding up a bottle of Aleve. The camera pulls back, as if to show that Kevin’s story has wide application, and he says, in a triumphal way, “For my pain I want my Aleve!”

Why, you wonder — if you are an overthinker, like me — would Kevin agree to give up “his” Aleve? Why would he want to prove to us that Aleve is better for him than Tylenol is, especially when he appears to have already known this? Why choose a deliveryman to act as spokesperson/guinea pig for the product? Well, yes, the work he does is physical, so that makes sense with regard to knee pain, but maybe the ad-makers also knew that “delivery” is a quasi-medical term for the varying methods of administering drugs? And, finally, there’s that hint of whining in Kevin’s complaints about having to take more pills, to make “another pill stop,” and in the commercial’s dramatic high point: “Can I get my Aleve back yet?” As if this voluntary “experiment” had turned into a cruel deprivation by disembodied hands and unseen forces.

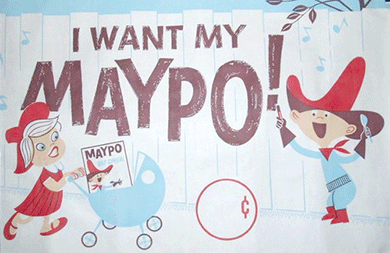

But it’s the use of the word “my” here that poses the most questions for the overthinker. It puts this particular OT in mind of another TV commercial — an old, less guileful ad for a breakfast cereal in which a cartoon child sits on a stool and declares, “I want my Maypo!” The child is at once powerless and proprietary — it’s “my Maypo,” as it is, for Kevin, “my Aleve.” But at least toddlers are entitled to talk like toddlers. “My” is of course everywhere in advertising and marketing these days, especially online: mymedicare, mygofer, mygolfspy, myregistry, myjailbreakmovies, mykleenextissue, mykrispykremevisit, myplymouth, mytraderjoes, myslimquick, mybowlingvacation, mybayerjob, and on and on. It even crept into yourPresident’s State of the Union address, when he introduced us to MyRA — the My Retirement Account. This locution has grown like marketing kudzu, becoming not only popular but almost necessary for promotional campaigns, government resources such as mymedicare.gov and mydmv.ny.gov, and in advertisements for products and services.

But it’s the use of the word “my” here that poses the most questions for the overthinker. It puts this particular OT in mind of another TV commercial — an old, less guileful ad for a breakfast cereal in which a cartoon child sits on a stool and declares, “I want my Maypo!” The child is at once powerless and proprietary — it’s “my Maypo,” as it is, for Kevin, “my Aleve.” But at least toddlers are entitled to talk like toddlers. “My” is of course everywhere in advertising and marketing these days, especially online: mymedicare, mygofer, mygolfspy, myregistry, myjailbreakmovies, mykleenextissue, mykrispykremevisit, myplymouth, mytraderjoes, myslimquick, mybowlingvacation, mybayerjob, and on and on. It even crept into yourPresident’s State of the Union address, when he introduced us to MyRA — the My Retirement Account. This locution has grown like marketing kudzu, becoming not only popular but almost necessary for promotional campaigns, government resources such as mymedicare.gov and mydmv.ny.gov, and in advertisements for products and services.

What is this mystuff all about? It may be obvious, I tell, er, myself, but it’s still worth making explicit: It’s a manipulative, essentially phony syntactical ceding of brand ownership to the consumer, an attempt on the part of ad people and marketers, witting or otherwise, to instill in us a (worthless) sense of proprietorship over the products and services we consume. To paper over any thought of corporations, production, bureaucracy, and profit. To make the customer feel hegemonic when in fact he or she is in economic terms more nearly peonic.

There’s nothing to be done about this mytrend, except to object and hope it subsides. You might occasionally, in ordinary discourse, deploy “the,” or something else, or nothing at all before nouns relating to things that are genuinely in your possession. That is, not “my book” but “the book,” or “this headache” instead of “my headache.” It’s a skirmish at best, maybe to be joined only by this one lonely guerilla, but it feels good to try.

Daniel Menaker’s memoir, titled, unfortunately in this context, My Mistake, has recently been published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.