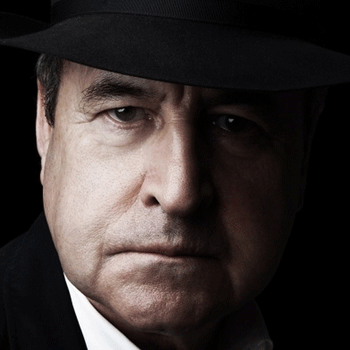

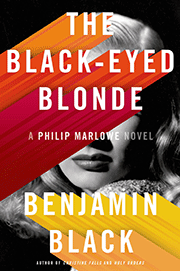

The Black-Eyed Blonde: A Conversation with John Banville

John Banville on Raymond Chandler, literary inhabitation, and the stylish prose of dishwasher instruction manuals

When John Banville came to New York earlier this month, I met him for breakfast at the London Hotel. In his new novel, The Black-Eyed Blonde (Henry Holt), he has the narrator grouse about the phony Irish pubs of Los Angeles, but this hotel restaurant seemed sufficiently like a hotel restaurant in London to escape Banville’s condemnation. We both ordered coffees and began to talk about the narrator in question: Philip Marlowe.

Banville is the second writer, after Robert B. Parker, to get permission from the Raymond Chandler estate to write a Marlowe novel. Although one suspects that Banville’s prizewinning work written under his own name — novels like The Book of Evidence, The Sea, and Ancient Light — played a part in his getting permission to take over from Chandler, the new book is credited to Benjamin Black, Banville’s alter ego, who has written a series of crime novels featuring a pathologist in the Dublin morgue named Quirke. As businessmen came and went from the tables around us, Banville and I talked about Quirke, Marlowe, Los Angeles, and the stylish prose of dishwasher instruction manuals.

CC: How did this book get off the ground? Did you approach the Chandler estate or did they approach you?

JB: Well, it’s boringly simple, because my agent Ed Victor is also the agent for the Raymond Chandler estate. He came to me about three years ago and said “Why don’t you do a Philip Marlowe novel?” I’d read Chandler since I was in my early teens. My older brother introduced me to him. And the discovery of Chandler was wonderful! Because before then I had read mostly the English crime novelists. Ladies in flowered frocks with murder in their hearts, you know? Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Josephine Tey, Margery Allingham. A whole slew of them. But they wrote mainly crossword-puzzle books — with great skill; I’m not dismissing them — but it was like doing a crossword puzzle. And at the end of it you’d have the slightly ashen feeling you have when you’ve finished a crossword puzzle and you think “What did I spend all my time doing that for?” Chandler offered something completely new. As he said himself, what he was after was “richness of texture.” When he started doing stories for Black Mask and other pulp magazines the editors would always cut out his descriptive bits. They would say to him, “Look, our readers are only interested in action.” And Chandler set out to disprove this. He said that readers thought they were interested in action, but they would accept that richness of texture. They would accept emotion generated through dialogue and description. He reinvented crime fiction. Or he invented a new genre of fiction: rich, funny, first-person, narrative, allusive. And he said, “By doing this, I can introduce even semi-literate readers to good writing.” I love that democratic American thing. One of the things I loathe about modernism — the whole modernist venture — was contempt for the audience, contempt for the readership. Why not get people to read?

When The Sea was published, eight or nine years ago, my wife was in Marks & Spencer and the woman at the checkout saw her credit card and said, “Are you related to John Banville? Tell him The Sea is the most beautiful thing I’ve ever read, and tell him that came from a checkout woman at Marks & Spencer’s.” The best review I’ve ever had was three words long. It was in ’89 when The Book of Evidence was short-listed for the Booker Prize and I had about three and a half minutes of fame. I was going to the train one morning, to go to my job at the Irish Times, and a workman passing by on his bicycle saw me and he veered toward me. I thought “God, I’m going to be attacked.” Just before he got to me, he swerved away and said, “Great fucking book!”

CC: Is that why you started writing as Benjamin Black: to reach more people?

JB: No, I don’t think it was. I’d like to claim that it was, but I don’t think so. I intended to do one book, and I’ve now done seven. It’s been a great adventure. I mean, look, it may have been a mistake. Who knows?

CC: Why do you say that?

JB: Oh, well, one can never judge one’s own work. I was interviewed recently by a very earnest German intellectual journalist, and he said to me, “Mr. Banville you are a great writer, vy are you writing zis trash?”

CC: How was the experience of writing a Marlowe book different from the Quirke novels?

JB: It was easier. First of all it was in the first person. First person’s much easier. And I found that I could do Chandler, could do his voice. I read a few of the books again. I read the letters, read the essays, and I got myself inside Chandler. He’s a very strange, complicated man. He’s far stranger and far more complicated than he realized himself, I think. He was born in Chicago, went to school at Dulwich College, where P. G. Wodehouse went to school. His uncle gave him £500, he came back to America, worked at odd jobs. He had a job with an oil company, from which he was dismissed for absenteeism, alcoholism, and moral turpitude — he kept seducing the secretaries. He was fifty when his first Marlowe book, The Big Sleep, was published. And he was a very melancholy man, very lonely. He had that strange marriage to Cissy, who was eighteen years older than him, which made her nine years younger than his mother. I mean we all marry our mother to a certain extent, but boy, he did it in spades. He had a very odd attitude toward women. I think I’m right in saying that every single one of the Marlowe novels ends up with the killer turning out to be a woman.

And then of course poor old Chandler had that drink problem. You can see the influence of drink in the Chandler books. This is not a criticism . . . well I suppose it is criticism. You can see the mornings where he had a hangover, you can see the afternoons where he’d had a scotch or two, when he was writing and he just let it go. It’s usually not the prose, it’s the action. He starts to explain the action.

CC: Where do you think your novel fits into the other Marlowe novels?

JB: I can’t say which book it’s a sequel to, but it’s a sequel to one of them. If I say which one, everyone will know what the ending is. I had great fun tying up all of the strings that would attach it to the earlier book. I like that kind of intricacy. On sleepless nights I would lie there doing the plot. Figuring it out. But I’d written nearly half of it before I said to myself, “John, you’ve got to figure out what’s going on.” Which I discovered subsequently is what Chandler used to do. Chandler would be almost near the end before he would figure it out. And frequently he didn’t figure out what was going on. He said, “I don’t happen to care who killed Professor Plum in the library with the lead pipe.” He said, “It doesn’t matter a damn what a book is about. Style is the only thing that will endure in writing.” That appealed to me.

He’s a great stylist, in his way, though he does overwrite at times. I think he also had a certain contempt for himself. He felt that he could have done better, that he could have been a “literary novelist” as they would be called nowadays. I think this is foolish. There’s only good writing and writing that isn’t good. I remember the first dishwasher my wife and I bought, the instruction manual was written in the most beautiful English. It was clear, crisp, concise. It was just a beautiful piece of writing. Good writing can happen anywhere.

CC: How would you compare your Marlowe and Chandler’s Marlowe? Where do they diverge?

JB: I think the essence of Marlowe is his solitude and more than that his loneliness. He’s a very lonely man. No family, no friends. Lives in a rented house, no possessions. Chess board, and that’s about it. Coffee pot. He’s always battling sadness, battling loneliness. And that was what interested me most about him. Chandler makes him brutal at times, but I don’t think he was brutal at all. I imagine some critics will say that my Marlowe is too soft. But Marlowe is soft. He’s tough, but he’s not hard — that’s an essential difference. That’s the point of Marlowe, that he’s tough, and he’s courageous, and he believes in nobility. You know, a hero for our times. We need more of them.

CC: You’ve said that, compared to Marlowe, Quirke is a bit dumb.

JB: Well he’s just dumb like the rest of us. I mean dumb compared to Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot or all of these people. And Marlowe is closer to Quirke than to Holmes. He doesn’t see the clues. It takes him a long time to figure out what’s going on. He does figure it out in the end through persistence, but not through being a genius. There’s no such thing as Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot.

CC: Marlowe waits around for the next thing to happen, and reacts to it.

JB: Yeah. The guy who comes through the door with a gun in his hand. Chandler said that when you’re stuck just have a guy with a gun in his hand come through the door — so I had a guy come through the door with a gun in his hand. A Mexican guy with a gun in his hand.

CC: Did you find it easier to work humor into the novel with Marlowe than with Quirke?

JB: Quirke is not much fun, is he? My Spanish publisher said “I love Quirke, but please, can you just lighten him up a little bit?” Quirke is far more damaged than Marlowe. Quirke’s past is so black, and his sins are so many and so huge that there’s not much room for humor. But it’s also very difficult to do humor in a crime fiction. It’s either over-the-top, or it’s so mild as to be inexistent. Marlowe’s able to do a sort of wry humor. It’s not exactly sidesplitting but he’s witty.

CC: Where did your title come from?

CC: Where did your title come from?

JB: It’s Chandler’s own title. He’d written a list of about twenty possible titles and this was one of them, and I was well into the book before my agent remembered this list, sent it to me, and said, “Wouldn’t The Black-Eyed Blonde be a great title for you?” So I immediately changed the hair color and the eye color of Clare Cavendish. If somebody had said to me twenty years ago, “One day, John, you’ll publish a book called The Black-Eyed Blonde,” I would have said “What? Ridiculous!” As I get older I get more playful and irresponsible.

CC: Do you plan to keep writing Benjamin Black novels?

JB: Oh, I think so. Or I might invent somebody else. As a friend of mine said “You’re Banville pretending to be Benjamin Black pretending to be Raymond Chandler. Where will it end?!” I said “My next project is I’m going to write a Harry Potter novel.” But first this summer I’m planning a new Benjamin Black novel set in contemporary Ireland. The possibility of which terrifies me, as I know nothing about contemporary Ireland. I mean I’ve been sitting in a room for the past fifty-five years writing. And I certainly don’t know anything about the world of the young.

CC: How will you manage it?

JB: I’ll fake it I suppose. I’ll make it up. I mean it’s amazing how persuasive made-up stuff is. I remember talking to Jim Crace about his book Being Dead, which has lots of complicated forensic biological detail. I said, “Jim, where’d you get all this?” and he says, “I made it up!” And I remember saying to Cormac McCarthy once, after All the Pretty Horses had come out — and really I should have known better — “Cormac, you must have been brought up with horses, no?” and Cormac says, “I don’t know anything about horses.”

CC: Are you working on a new John Banville novel as well?

JB: Oh, I’m always working on a John Banville novel. I can put it aside, but it’s always in the back of my mind. The John Banville books are so bloody difficult. They’re so tedious. The Benjamin Black books are such fun. Before I became Benjamin Black I never worked spontaneously. Everything I did was the result of deep, deep, deep concentration. The thing about being Benjamin Black is, it’s like being a tightrope walker. You have to keep risking, have to keep saying, “Just leave it, just leave it. Go on, go on, go on, don’t pause or you’ll fall off.” Whereas Banville is down under the ground, a mole blindly digging his way through the dark. So I’m very lucky to have these two opposing ways of working. The mole and the tightrope walker.