On Joyce and Syphilis

New evidence of the author’s suffering, and reflections on the scholarly debate

In 1917, while walking down a street in Zurich, James Joyce suffered an “eye attack” and remained frozen in agony for twenty minutes. Lingering pain left him unable to read or write for weeks. Joyce had endured at least two previous attacks, and after the third he allowed a surgeon to cut away a piece of his right iris in order to relieve ocular pressure. Nora Barnacle, Joyce’s partner, wrote to Ezra Pound that following the procedure Joyce’s right eye bled for days.

Joyce was suffering from a case of glaucoma brought on by acute anterior uveitis, an inflammation of his iris. It was, unfortunately, nothing new. Joyce’s first recorded bout of uveitis was in 1907, when he was twenty-five years old, and the attacks recurred for more than twenty years. To save his vision, Joyce had about a dozen eye surgeries (iridectomies, sphincterectomies, capsulectomies) — every one of them performed without general anesthetic. He lay in dark rooms for days or weeks at a time, and his post-surgical eye patches became his trademark. Doctors applied leeches to siphon blood from his eyes. They gave him atropine and scopolamine, which cause hallucinations and anxiety, to dilate his pupils. They administered vapor baths, sweating powders, cold and hot compresses, endocrine treatment and iodine injections. They prescribed special diets (oatmeal and leafy vegetables) and warmer climates. They disinfected his eyes with silver nitrate, salicylic acid, and boric acid; instilled them with dionine to dissipate nebulae; and doused them with cocaine to numb the pain. Nothing really helped.

Uveitis raises intraocular pressure and produces a sticky exudate, which caused Joyce’s irises to attach to the lenses behind them. Sometimes the exudate was so thick that it congealed and blocked his pupil altogether — his future publisher Sylvia Beach remembered seeing his eye “covered by a sort of opaque curtain.” The increased pressure caused glaucoma, which eroded his optic nerve over the years, making his vision spotted, narrow, and dim.

By the age of forty-eight, Joyce’s left eye functioned at only one-eight-hundredth the normal capacity and his “good” eye at one-thirtieth. His eyeglasses prescription was +17 in both eyes — severely farsighted. One of the twentieth century’s great novelists often required a magnifying glass to read anyone’s writing, including his own. Each new attack brought him a step closer to blindness, and the consequent threat to his literary career contributed to a series of nervous breakdowns.

Joyce lived a thoroughly documented life, but the cause of his lifelong battle with uveitis has never been definitively named. Before the introduction of penicillin in the 1940s, the most common cause was syphilis, and because Joyce had begun visiting prostitutes at the age of fourteen, rumors began circulating that his chronic problems had been sexually transmitted. But the image of a syphilitic Joyce is one that few scholars have wanted to conjure in print. Richard Ellmann, Joyce’s preeminent biographer, had access to extensive biographical materials and didn’t even mention the possibility of syphilis — and yet he had no qualms diagnosing Oscar Wilde with syphilis despite questionable evidence. Joyce’s patron Harriet Shaw Weaver, his grandson Stephen, and Nora Barnacle all destroyed letters from Joyce, raising the question of whether allies were protecting Joyce’s reputation from the stigma of a dreadful disease.

Unlike gonorrhea and chlamydia, a case of syphilis was often a prolonged, multi-systemic affliction. It begins when a person comes into contact with a pale, corkscrew-shaped bacterium called Treponema pallidum that gathers in lesions on an infected person’s skin and genitalia. Once the microbe enters the body, it can lurch and coil its way into virtually every type of tissue it encounters: blood vessels, muscles, joints, nerves, cerebrospinal fluid, and vital organs are all potential targets, and any two cases might present substantially different symptoms. Periods of increased spirochete activity alternate with dormant periods, and the advanced stages sometimes led to what in Joyce’s time was called “general paralysis of the insane,” which could cause abrupt psychosis, erratic personality transformation, memory loss, or grandiose delusion. Raising suspicions of syphilis in virtually any public figure (Lenin and Nietzsche are two examples) stirs controversy because a syphilis diagnosis potentially tarnishes a person’s life and accomplishments, be they a political regime, a philosophy, or Finnegans Wake.

Before penicillin, treatment for syphilis amounted to taking tolerable doses of poison, and about a third of patients who were subjected to these remedies never overcame their infections. Mercury pills and ointments were popular for centuries, though mercury was toxic to bacteria and patients alike, and extended treatment weakened syphilitics until their teeth, hair, and fingernails began to fall out. By 1910, doctors had started using a German drug called Salvarsan (arsphenamine), an arsenical compound that reduced arsenic’s toxicity while keeping much of its treponemicidal properties. Salvarsan was the first modern chemotherapy, but it was as flawed as it was revolutionary. In addition to being only partially effective, Salvarsan had harsh side effects and killed hundreds of patients before it was replaced by a less effective, closely related version called Neosalvarsan. These limited medical options meant that a person diagnosed with syphilis before World War II could expect a long, hard battle with the disease if it persisted past the primary stage.

Joyce’s medical history — which I’ve pieced together from decades of published and unpublished letters and documents — appears to be a painful journey through all of syphilis’s stages, beginning with his initial contraction in the red-light district of Dublin or Trieste, where Joyce lived for over a decade. In a diary, Joyce’s brother Stanislaus described him in 1907 as having not only inflamed eyes but also stomach problems and various “rheumatic” pains. He was bedridden for weeks, and at the end of an illness lasting nearly three months, he walked around at an “invalid’s pace.”

After the first month of illness, Stannie wrote in his diary that his brother’s right arm had become “disabled,” and that it had remained that way for about a month while Joyce received electrotherapy treatment. What exactly Stannie meant by “disabled” has been a vexing question for Joyceans. If the joints in Joyce’s right arm were stiff and inflamed, he may have had a form of rheumatism. But if his arm was paralyzed or “paretic” (partially paralyzed), then it may have been a symptom of neurosyphilis. This would mean that the spirochete had begun to attack Joyce’s nervous system — presumably nerves in his right shoulder or arm.

As it turns out, Joyce’s right shoulder had a curious little medical history all its own. Years later, Joyce complained of pain in that shoulder and claimed that his right deltoid muscle had atrophied. In the midst of more eye troubles in 1928, his right shoulder had what he called a “large boil.” For anyone hunting for signs of syphilis, the boil sounds like a late-syphilitic lesion: they occur asymmetrically on the body, are typically large, and sometimes merge to form a single wound.

By 1922, Joyce and his friends had begun subscribing to a now-discredited theory of infection postulating that various ailments were caused by infections migrating outward from just a few bodily sources, particularly the oral cavity. So they started blaming Joyce’s uveitis on his bad teeth, and in two harrowing visits in 1923 a dentist extracted seventeen teeth, seven abscesses, and a cyst from Joyce’s mouth. His eye problems nevertheless continued, suggesting that syphilis may also have caused Joyce’s dental calamity. The disease, after all, frequently causes oral ulcers as well as periodontitis (a reason to extract affected teeth). A syphilitic Joyce would presumably have had colonies of Treponema in his weak eyes, his right shoulder, and his wretched mouth.

But maybe not. Sometimes a boil is just a boil. Diagnosing a person seventy years after death can be a dubious enterprise, and identifying syphilitic lesions requires a degree of detail about Joyce’s condition that we simply don’t have. A posthumous diagnosis of syphilis is particularly perilous because the disease’s symptoms are mind-bogglingly numerous. Treponema’s nearly free rein in the human body means that syphilis can cause headaches, sore throats, nausea, impotence, incontinence, dull or stabbing pain, alopecia, arthritis, jaundice, thrombosis, aneurysms, epilepsy, meningitis, inner and outer bone infections, and arteriosclerosis. And this is a partial list — the array of ocular problems is daunting all by itself. Add to all of this the fact that any two cases might affect completely different organs and that an infection might range from negligibly mild to catastrophically serious, and syphilis begins to seem as complicated as any Joycean text.

All were respectfully silent about Joyce’s condition until an Irish doctor named F. R. Walsh wrote an article for the Irish Medical Times in 1975. According to Walsh, Joyce’s father told a group of medical students in 1920 that he’d contracted syphilis while a medical student and cauterized his own lesions with carbolic acid. Inspired by Walsh’s scoop, an Irish journalist named Stan Gebler Davies added a two-page appendix to his Joyce biography, published months after Walsh’s article, claiming that congenital syphilis had caused James Joyce’s chronic uveitis. Davies was wrong — Joyce had no symptoms of congenital syphilis — but the issue was suddenly wide open.

In 1980, also apparently inspired by the Irish Medical Times article, a comparative literature Ph.D. named Vernon Hall and a medical doctor named Burton Waisbren reread Ulysses with a syphilitic author in mind, and they found syphilis everywhere — in Stephen Dedalus’s “somewhat troubled” sight, in Leopold Bloom’s verbal lapses, in the death of Bloom’s infant son. Their journal article for Archives of Internal Medicine includes a two-page table listing apparent references to syphilitic symptoms throughout Ulysses, among them “Stephen grimaces,” “Bloom and bowel problems,” “Bloom blunders stiff-legged,” and “Stephen staggers.”

Hall and Waisbren explained that “the repetitive use of the letter s as a code symbol for the word ‘syphilis’ occurs throughout the book.” They pointed out that a Ulysses word index requires a remarkable eighty-one columns to list all the novel’s s-words. “The letter ‘s’ hisses throughout the book as a reminder of the ‘s’ in syphilis (a word that not only begins but also ends with ‘s,’ as does the novel).” Molly Bloom’s final “Yes” was no longer her languid, rapturous refrain as she drifts off to sleep. It became the ominous whisper of a disease she presumably contracted from the husband lying next to her in bed.

The investigations went deeper. In 1995, Kathleen Ferris, then an assistant professor at Lincoln Memorial University, published James Joyce and the Burden of Disease, the first book laying out a case for a syphilitic Joyce. Ferris swept through Joyce’s biography and works, venturing much further into the issue than anyone before, and her conclusions were ambitious. She argued that Nora Barnacle had serious syphilitic complications, that their daughter Lucia suffered from insanity brought on by neurosyphilis, and that Joyce developed a form of advanced neurosyphilis — tabes dorsalis — which causes a distinctive doddering gait called locomotor ataxia. Hall and Waisbren had tabes in mind when they noted the staggering Stephen and the stiff-legged Bloom, and Ferris used tabes to explain Joyce’s peculiar habit of walking around with an ashplant cane. She went on to suggest that tabes left Joyce impotent and incontinent before giving him the intestinal ulcer that killed him at the age of fifty-eight.

The nature of Ferris’s work made a troubling idea even more difficult to accept. When her argument needed help, she crossed from Joyce’s biography into his fiction, including into the tangled puns of Finnegans Wake. She argued, for example, that Joyce encrypted the word “Salvarsan” in the phrase “the repleted speechsalver’s innkeeping” (her emphasis). Signs that anyone in Ulysses had syphilis counted as evidence that Joyce had syphilis, and this raised perennial questions about how to use literary evidence. When Ferris’s publisher sent an advance copy of her book to the director of the Zurich James Joyce Foundation, Fritz Senn, he responded with a detailed critique. Senn tried to dissuade Ferris from claiming that Joyce invokes gonorrhea and syphilis with the sound of applause in Ulysses (“Clappyclapclap”) and that the “sand in the Red Sea” harming a sailor’s eyes is really code for spirochetes in the blood. “You are throwing sand in your readers’ eyes,” Senn wrote to her. She kept the readings anyway. Cautious or not, Ferris was the first scholar willing to argue that Joyce suffered privately with venereal disease for the majority of his life, and her dedication to this idea required no small amount of bravery.

Senn was one of many skeptical Joyceans in attendance when Ferris presented her research at a 1995 Joyce conference in Miami. Joseph Kelly, a professor at the College of Charleston, remembered that for her everything pointed to syphilis. “If Joyce had written in a letter, ‘I don’t have syphilis,’ she would have seen that as evidence that he did.” Ferris’s conviction, many thought, was unwarranted. I repeatedly contacted Ferris this past winter and spring hoping to hear more about her struggle to revise Joyce’s biography so radically, but she did not respond.

The most vehement reaction to Ferris’s work came from J. B. Lyons, who was an Irish doctor, a Joyce enthusiast, and, apparently, a defender of Irish virtue. One Joycean, Frank Delaney, recalls how irritated Lyons became at the subject of Joyce’s syphilis, which he considered a British smear against an illustrious Irish artist. “If the English can’t get you one way they’ll get you another,” Lyons grumbled. Lyons (who died in 2007) took it upon himself to quash syphilis rumors in a 1973 book called James Joyce and Medicine and a 1982 symposium lecture later published in his essay collection, Thrust Syphilis Down to Hell. When Ferris’s book came out, Lyons wrote a review deriding her argument as “a facile degradation of a great writer.” He followed it up with an article for the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences in which he repeatedly reminded his readers that he was a medical doctor, a credential that apparently doubled as a license to mock a handful of Ferris’s arguments while ignoring the others. His favorite rhetorical weapon was outraged exclamation: “This suggestion is preposterous!” “What a derogation of self-identity!” “What evidence is there that Nora Barnacle contracted syphilis? None!” Ferris was, for Lyons, a dilettante stumbling around outside of her proper professional realm. The debate was simultaneously expansive and minuscule, and it highlighted the way large conclusions can rest on the smallest textual pieces. For example, Lyons and Ferris marshaled the same Joyce letter to support their opposing arguments, which hinged on their differing interpretations of the word “it.”

In lieu of syphilis, Lyons proposed the only other reasonable diagnosis: an autoimmune affliction called Reiter syndrome, which afflicts roughly three in 100,000 men under thirty-five (whereas estimates of syphilis rates in European cities were roughly 10 percent in Joyce’s day). The syndrome is typically triggered by chlamydia or a gastrointestinal infection and lasts from two to six weeks, featuring three telltale symptoms: arthritis, urethritis, and conjunctivitis (an inflammation of the eye’s outer membrane). To fit this diagnosis, Lyons interpreted Joyce’s “disabled” right arm in 1907 as a particularly nasty case of arthritis.

But to claim that Joyce had Reiter syndrome is to claim that he had a particularly rare version of a rare illness. One of the largest studies of the syndrome followed an outbreak among Finnish soldiers at an army hospital on the Russian front in 1943. Among the 344 cases documented, over two-thirds of the patients suffered from conjunctivitis, while only eleven had uveitis. Going deeper into the pathology makes Joyce’s case seem more anomalous. His eye problems were recurrent — they disappeared and reappeared for decades — which is exactly what we would expect from syphilis, but such prolonged recurrence rarely happens in Reiter syndrome. A 1960 study estimated that the annual risk of recurrence is about 15 percent, and the study of Finnish soldiers placed those odds far lower. Moreover, the syndrome rarely causes arthritic arms. The vast majority of cases affect the lower limbs, and when arthritis does occur it is unlikely to “disable” anything. The Finnish study reported that most cases featured “relatively mild” joint tenderness and that patients suffered only partially limited movement.

And so a doctor thinking about diagnosing Joyce with Reiter syndrome would have encountered an assemblage of ill-fitting facts: Joyce had problems with upper-body movement rather than lower-body movement. He had uveitis instead of conjunctivitis. His problem recurred for decades instead of weeks. His episodes were acute rather than mild. We have no indication one way or another if he had urethritis at any point after 1904. Taken together, these inconsistencies make it hard to accept that Joyce had Reiter syndrome — which was the most likely alternative to syphilis.

For some, the uncertainty surrounding Joyce’s condition has turned the issue into his most captivating puzzle. Erik Schneider, an independent scholar, became particularly fascinated. Schneider had dropped out of the University of California, Santa Barbara in 1972 and spent years educating himself at the school’s library. His abiding interest in Joyce eventually drove him to Dublin, and later to Trieste (following a brief period in London inspired by a similar devotion to the Sex Pistols), where he read Ferris’s groundbreaking book in the late 1990s. The emergence of this new dimension in Joyce studies — something glossed over by Ellmann, something that divided Joyceans — inspired Schneider to begin avidly pursuing Joyce’s medical records. “I went over half of northern Italy looking for them,” Schneider told me in February. From memoirs and clinical archives, he gathered impressive pieces of evidence suggesting Joyce had syphilis. An expanded edition of his book, Zois in Nighttown, which is out this week, compiles a vast number of references to syphilis and prostitution in Joyce’s life and works.

About the only things Schneider didn’t find were Joyce’s medical records (though he hasn’t given up), and over the years the syphilis controversy died down. Ferris left the academy, and scholars’ vision of Joyce remained more or less unchanged. Gordon Bowker’s 2012 biography of Joyce is the most serious treatment of Joyce’s life in years, but it notes only in passing that Ferris’s argument for a syphilitic Joyce “is not entirely improbable.” Bowker’s book is the eighth biography of Joyce and the eighth to leave the writer’s body a cipher. That, in any case, is how it appeared to me when I began to examine Joyce’s medical biography for my recently published history of Joyce’s censorship struggle, The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses. From my perspective, Joyce was going blind, and there was no clear reason why.

The key to unlocking James Joyce’s medical mystery isn’t in his eyes, his teeth, his boils, or any of his nagging symptoms. It’s in his treatment. In 1928, Joyce walked into Dr. Borsch’s eye clinic in Paris after his latest episode of eye problems and with a large boil on his right shoulder. The doctor, following his clinical examination, considered two possible treatments.

The first was “a cure of I have forgotten what,” as Joyce put it in a letter to Harriet Shaw Weaver, though he left an important clue about the unnamed cure when he added that “the drug in question had had a bad effect on the optic nerve.” Possibly the only drug that could have helped a patient’s uveitis while potentially harming the optic nerve is Salvarsan; while Salvarsan might have killed the spirochete causing Joyce’s uveitis, one of the drug’s side effects was that it caused optic neuritis in about one in forty patients.

Whether or not “the drug in question” was Salvarsan (or Neosalvarsan), Joyce decided to take Dr. Borsch’s more mollifying medication. In October of 1928, Joyce, nearly blind, dictated two letters that explained his condition and Dr. Borsch’s treatment essentially the same way: “They are giving me injections of arsenic and phosphorous but even after three weeks of it I have about as much strength as a kitten and my vision remains stationary.”

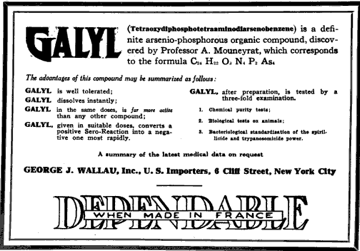

What decades of Joyce biographers have overlooked is that the chemical compound of arsenic and phosphorus is a little-known medication called Galyl (phospharsenamine). And doctors administered Galyl only as a treatment for syphilis. Galyl’s properties fit all the descriptions in Joyce’s letters. It was injected intravenously in extended regimens — the researchers who developed it, in fact, suggested a course of precisely three weeks. (At least one doctor, writing for American Medicine, seconded the three-week recommendation.) While other arsenicals often caused nausea and vomiting, Galyl improved a patient’s appetite. Joyce reported having a “ravenous appetite” after the injections, and his physician would have valued this advantage of the medication because Joyce’s weight had become alarmingly low. At five feet ten inches tall he weighed less than 125 pounds.

But the most telling fact is that Galyl was the only injectable compound of “arsenic and phosphorus” around. Various pharmacopoeias, national formularies, and pharmaceutical dispensaries of the 1910s and ’20s all indicate the same thing — no other medication fits Joyce’s description, nor could he have received separate injections of arsenic and phosphorus because both elements are highly toxic — probably lethal — even in relatively small doses. The unavoidable conclusion is that Joyce’s doctors gave their sickly patient Galyl in 1928. James Joyce was treated for syphilis.

Joyce’s “arsenic and phosphorus” injections were an unremarkable detail buried in his overwhelming medical history (Richard Ellmann’s biography mentions them without comment) because Galyl is only a blip in the long history of syphilis treatments. In fact, the treatment enjoyed its brief vogue for purely political reasons: Salvarsan and its variants were German products, and the outbreak of World War I left British doctors rushing to find an alternative after the British government suspended the patents and trademarks of German antisyphilitics. French researchers developed Galyl in 1914, and its national origin made it a patriotic wartime substitute in Allied countries.

Advertisements touted the fact that Galyl was “made in France” because its Frenchness was a bigger selling point than its effectiveness. As it turned out, the more-toxic German drugs were simply better, which is why Galyl fell out of favor so quickly after the war. And yet Dr. Borsch apparently prescribed it to Joyce because the terror Joyce harbored about his incipient blindness left him adamantly opposed to any medication that might further damage his eyes — “that ended that for me,” Joyce wrote to Weaver about learning that the unnamed drug affected the optic nerve. And so when Joyce refused the conveniently forgotten “cure,” Dr. Borsch would have administered the only available substitute he knew out of an abundance of caution for the famous writer’s career. Unfortunately, taking the safest option for Joyce’s eyes increased the chances that his syphilis would stick around — which it did.

Advertisements touted the fact that Galyl was “made in France” because its Frenchness was a bigger selling point than its effectiveness. As it turned out, the more-toxic German drugs were simply better, which is why Galyl fell out of favor so quickly after the war. And yet Dr. Borsch apparently prescribed it to Joyce because the terror Joyce harbored about his incipient blindness left him adamantly opposed to any medication that might further damage his eyes — “that ended that for me,” Joyce wrote to Weaver about learning that the unnamed drug affected the optic nerve. And so when Joyce refused the conveniently forgotten “cure,” Dr. Borsch would have administered the only available substitute he knew out of an abundance of caution for the famous writer’s career. Unfortunately, taking the safest option for Joyce’s eyes increased the chances that his syphilis would stick around — which it did.

The disputes surrounding Joyce’s condition underscore the fact that reading is a biased enterprise. Readers are not neutral observers. We read with the qualms, motives, and filters that help us find order in complicated texts, and the more elaborate a text is, the more likely a motivated reading will find whatever it’s looking for. Motivations can exaggerate the significance of s-words and obscure other details that don’t quite fit. When we aren’t reading too much into a text, we read too little of it.

Like all scholarship, the research surrounding Joyce’s biography has made a practice out of this selective blindness. Lyons and Ferris had opposite motives, but they both read Joyce’s injections of arsenic and phosphorus as nothing more than injections of arsenic. Ferris’s book misdescribes Joyce’s treatment as “injections of arsenic for three weeks,” omitting the key component entirely. Ignoring phosphorus altogether was convenient for both writers, as it allowed Ferris to argue that doctors treated Joyce for syphilis while permitting Lyons to insist that they were giving him arsenic for its “tonic” effects. Ferris read “arsenic” and thought, “Aha! Arsphenamine!” Lyons read “arsenic” and thought, “Aha! Fowler’s Solution!” — an over-the-counter tonic containing small amounts of arsenic (without phosphorus) that had been available from pharmacists and snake-oil salesmen since the eighteenth century.

Lyons disregarded the fact that Fowler’s Solution was never injected. Ferris focused on arsenic, apparently believed it was Salvarsan, and disregarded the likelihood that three weeks of the standard arsenical injections might very well have killed Joyce. Both readings treated “phosphorus” as irrelevant textual noise. Armed with interpretations that suited their purposes, Ferris and Lyons did not have a compelling reason to dig any further into pharmaceutical history, and so they didn’t. No one found the antisyphilitic medication written in Joyce’s letters because no one needed it.

To this day, Joyceans are not always perceptive about the issue. Luca Crispi, a well-known lecturer at University College Dublin, fumed in an interview in the Irish edition of the Sunday Times that my own research resembles “historical fiction.” The historical truth, according to Crispi, lies in the cast-off theory that oral-cavity infections cause uveitis — never mind that Joyce’s eye problems preceded his oral infections by more than a decade. It takes a special blindness to overlook basic chronology and a century of medical research: Crispi’s reaction is a form of kneejerk defensiveness about the extensive work of his academic field. The most unsettling prospect to certain Joyceans is not that Joyce’s life was ravaged by a sexually transmitted disease but that amid the mountains of scholarly research into Joyce’s acquaintances and influences, his primary-school education, his eating habits, his love letters, the songs he sang, and the marginalia he scrawled in his books, the most talked-about writer of the twentieth century has never really been seen.