World Cup Boom and Bust

Will a four-game stint as a World Cup host city improve life in Manaus?

The day before the United States played Portugal, the third of four World Cup games in Manaus, I watched a match on TV with Moeses Martins, a father of three who lives less than three miles from the city’s new stadium. Like thousands of families in the urban heart of the Amazon rainforest, the Martins live in a wooden house along one of the hundreds of igarapés — little rivers — that course through the city like veins.

That afternoon, the igarapé outside the family’s window was placid, but at halftime of the Germany–Ghana match in Fortaleza, Martins shared a cell-phone video of the stream swollen into a raging river, sweeping away pieces of nearby houses. “This was just last month,” he said, adding that when the annual floods run as high as they did this year, his neighbors will sometimes find alligators or snakes swimming in their living rooms. Then he showed me another clip from last May, when an electrical transformer across the stream exploded, igniting homes on the bank and sending black plumes of smoke across the neighborhood.

Incidents like these have made some people in Manaus furious about the World Cup. The argument that the money spent on preparations should have been dedicated to basic services has particular force in the capital of Amazonas, a city of nearly 2 million people surrounded by 2 million square miles of dense rainforest and accessible from Brazil’s other big cities only by plane or boat. Though the local soccer club, Nacional, hasn’t competed in the nation’s top division since 1985, the city is now home to the Arena Amazônia, a state-of-the-art $350 million, 40,000-seat stadium designed to look like a native straw basket, built for the Cup from steel imported from Portugal.

The Brazilian government argued that it was vital for Manaus to be a host city, in order to raise awareness of the country’s cultural and biological diversity, and to boost ecotourism. Yet despite Manaus’s location on earth’s largest watershed, one in four of its homes lacks running water, and its century-old sewer system accommodates under 10 percent of the population. A bright orange sign in the middle of the igarapé outside the Martins’ window warns against bathing, drinking, or fishing.

Yet the family was still watching the matches, sometimes gathering with thousands of others to view games on a giant screen at the FIFA Fan Fest in Ponta Negra, a river beachfront decked out with carnival games, a zip line, and hundreds of bored police officers toying with their stun guns. “We’re open to everyone who wants to visit,” said Martins, “but building hotels and everything doesn’t benefit that many people.”

Nearly 200,000 foreign and Brazilian visitors came to Manaus during the first two weeks of the Cup, the vast majority of them arriving at the city’s new international airport, where they were greeted by Budweiser girls offering free beers. It had been eight years since I’d been to Manaus, and although it hadn’t received a promised light-rail system, evidence of recent construction was everywhere. The central market by the port had been refurbished. A two-mile-long bridge now spanned the Rio Negro, the largest tributary of the Amazon, connecting Manaus to farmers and businesses in surrounding counties. The city’s booming industrial district and construction businesses had attracted thousands of new immigrants from Argentina, Colombia, Haiti, Venezuela, and far-flung parts of Brazil. And thousands of miles of new fiber-optic cable had been laid to link the region to the country’s broadband network (though the connection often falters when the rains come). It was boom season in a city long haunted by cycles of boom and bust.

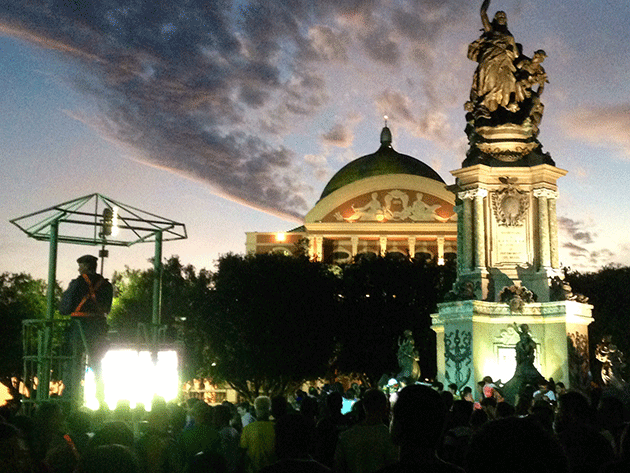

On the night of the U.S.–Portugal match at the Arena Amazônia, the historical center of Manaus was packed with fans, vendors, and security. Tourists and Brazilians alike were gathered at the foot of the Teatro Amazonas, an opulent opera house that was built during the rubber boom more than a century ago and briefly turned the city into the Paris of the Tropics. In those days, enterprising traders would loan boats and tools to local indigenous people for rubber-tapping season. At the end of the season, the traders would often collect the rubber, repossess their gear, and run off with tappers’ daughters as “payment” for false debts.

Such practices afforded the new rubber barons a lavish lifestyle of yachts, race horses, and pet lions — and enough extra coin to send their laundry to Europe. The public services they built in Manaus included an electric-trolley system, piped gas and water, and one of the world’s first street-lighting systems. In commissioning a Portuguese architect to build the Teatro with materials mostly imported from Europe, the state governor, Eduardo Ribeiro, scoffed at the cost. “When the growth of our city demands it,” he said, “we’ll pull down this opera house and build another.” But then a fellow named Henry Wickham smuggled thousands of rubber seeds back home for cultivation in Britain’s Asian colonies, and within a generation the price of Brazilian rubber had crashed.

Aside from a brief resurgence during World War II, Manaus was finished as a rubber town, and the Teatro went dim. But in 1967 Brazil’s military regime instituted a free port in the city, using tax incentives to draw manufacturers despite the lack of transportation infrastructure. These days the Free Economic Zone of Manaus hosts hundreds of factories, which produce cell phones and microwaves and Harley-Davidson motorcycles, and the Teatro Amazonas is once again a jewel in the town’s center. In 2005 the White Stripes played there, and during the World Cup the city’s elites gathered outside with foreigners to get smashed and take snapshots with whoever was sweating inside the Fuleco the Armadillo mascot costume.

When U.S.–Portugal ended in a dramatic 2–2 draw, a clutch of fans draped in American flags swarmed the commemorative statue in the plaza, singing “Seven Nation Army” to celebrate. “I didn’t even see the first goal,” one of them said. “I was too busy trying to get it on video.” The arrival of so many tourists had created beer vendors out of anyone with a bucket and some ice. Police marched through the drunken crowd in lazy formation. Half the men I talked to seemed to be P.E. teachers from Brazil, Portugal, or the United States, and all of them were using the same corny English pick-up lines to get women’s attention.

Beyond the security perimeter, rats and street dogs were already sniffing through the waste. I retreated to a small bar across the street from Plaça da Saudade, a quiet park built on what used to be a cemetery, where I found locals who hadn’t wanted to pay triple the normal price for beer playing dominoes and listening to Brazilian pop.

Marcelo Henrique Soares, a former dentist turned detective, told me he hadn’t been to a game. “I’m not giving a dime to FIFA,” he said. “You know they’re not paying taxes on any of this?”

On my last night in Manaus, I was sitting on a friend’s patio when we heard sirens and looked out to see a glittering motorcade escorting a bus to the new stadium. I counted sixty police vehicles before giving up. The Swiss team was en route to practice before its match the next day against Honduras — the final game to take place in the Amazon. A helicopter traced their every turn with a spotlight.

On the living-room television, the local news was broadcasting an update on an accident earlier that afternoon. A tugboat had collided with a nearby bridge, collapsing the structure and crushing a critical water line. By match day, it would emerge that 300,000 people in thirty neighborhoods were without service. The president of the local water-and-sanitation company, Manaus Ambiental, was on vacation, but he announced that he would return immediately to find a solution. He advised people to start saving water in the meantime. There was no telling how long it would be before the system was fixed.