William Deresiewicz on Excellent Sheep

William Deresiewicz discusses the miseducation of the American elite

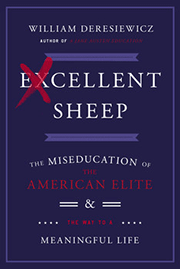

William Deresiewicz is an underappreciated essayist and thinker, not to mention a literary critic whose acumen is comparable to James Wood’s. After writing an essay he felt was doomed to obscurity, “The Disadvantages of an Elite Education,” he received such a strong response he decided to expand on his critique. The result, Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite & The Way to a Meaningful Life, is a rangy and urgent diagnosis of the compromised higher-education system in the United States. A former professor at Yale, Deresiewicz is particularly adept at articulating the kinds of unspoken assumptions — for example, that the ethos of college should be practical and professional, and that success should be defined comparatively — that make many academics and students vaguely uneasy. Given that Excellent Sheep is at heart instructive, I asked Deresiewicz six questions from the perspective of one of the students to whom it is foremost addressed.

1. Reading Excellent Sheep was somewhat therapeutic, even vindicating for me. My undergrad institution, from which I graduated two years ago, is what’s commonly called a “Boutique School,” a regional college offering something resembling the traditional liberal-arts education of which you approve. In retrospect, I seemed to have never appreciated what a gift this was; it was one of my last opportunities for uninhibited intellectual play. Do you think it falls on the student to have this realization, in the face of pressure to succeed by traditional metrics?

I’d love it if elite college students expected themselves to take the opportunity for uninhibited intellectual play. But no, I don’t think it falls on them to have that realization — at least, not primarily. It falls on the adults they encounter in high school and college to make sure they understand that that is one of the most important opportunities that college provides. As things stand now, almost everything is pushing in the opposite direction. Fortunately, there are professors and even colleges (often liberal-arts colleges or public-honors colleges) that try to get students to resist the rush to practicality and credentialism.

2. Continuing in this vein, and considering your commentary on parenting and teaching, I wonder if parents and teachers are truly capable of imparting certain lessons to their children and students, given how self-enclosed the world of a teenager or even a young adult can be. Is this solipsism biologically and psychologically innate, or is it a historical and cultural artifact of privilege — to wit, is this something that must be outgrown or can it be punctured by education? Like, would a teenager from a low-income home ever have these illusions?

Obviously, your historical/social/cultural position conditions your consciousness. But to suggest that the world of the young adult is entirely self-enclosed is to reject the idea of education altogether — the idea, that is, that it’s possible to become conscious of your position and think your way at least a little bit outside of it, as well as that adults can help you do that. Of course there are realizations a teenager is never likely to have, but that doesn’t mean that they can never have any.

3. One aspect of academic culture that I never truly recognized until it dissipated was its atmosphere of ambition. On the one hand this ambition incited me to work very hard, to be diligent and honest and demanding, to have goals and be excited about them; but on the other it shaped me into a monomaniac who harbored expectations of greatness and strongly identified with his intelligence. Do you think these two kinds of ambition are necessarily coupled? Cultivating the first kind, at least to me, seems worth it, while the other seems like a bottomless source of frustration, envy and anxiety.

I think you’ve put it exactly right (I also like “strongly identified with his intelligence”). There are two kinds of ambition, or two aspects of ambition, one good, one bad. The first one spurs you in a self-motivated way and puts you in relation to ideals of excellence (it’s too bad that word has been ruined by colleges); the second is all about comparing yourself to others and throws you into the Alice Miller cycle of grandiosity and depression. It’s probably inevitable that the two forms come together — I don’t think we can ever really get away from the second — but it’s worth becoming aware of it and resisting its tendency to control your inner life.

4. Which brings us to a word that appears often in Excellent Sheep: success. As the book turns to its instructive mode, you labor to define what you mean by “success,” and to demonstrate that it almost never happens without risk and failure — which, boy, does academia teach you to avoid. But you notice something else about our concept of success, something deeper, found in the history of literature: “Mailer wanted to be Hemingway, Hemingway wanted to be Joyce, and Joyce was painfully aware he’d never be another Shakespeare.” As you note, this hierarchical thinking applies to any vocation, and you admit that for every Hemingway who risked spectacular failure there are many people who didn’t become Hemingway. Our celebration of Hemingway starts to suggest to me that we see his life as more worthy than all the others against which it seems comparatively great. Why do we need this Bloomian shadow of success at all?

I think you miss my point about Hemingway et al. First let me say that I don’t labor to define success. Perhaps you got that impression because I don’t define it all. I say that you need to define it for yourself. As for Hemingway, what I’m saying is exactly that we should step away from that fevered existential race and from the idea that underlies it, which is that some lives are more worthy than others. Even Mailer, even Hemingway, even Joyce felt inferior to some ideal figure. Knowing that you can never overcome that feeling, in the race for status, can help liberate you from both the feeling and the race.

5. In Infinite Jest David Wallace wrote that “almost nothing important that ever happens to you happens because you engineer it. Destiny has no beeper; destiny always leans trenchcoated out of an alley with some sort of ‘psst’ that you usually can’t even hear because you’re in such a rush to or from something important you’ve tried to engineer.” I think you rightly champion “intuition” and “hunches” as acceptable guides to life decisions, because really it’s all we have. People cringe when they hear this, however, no one more than the college senior. From somewhere we’ve gotten this overly left-brained idea that life can be schematized, planned, quantified, corralled, controlled, or as Wallace wrote, “engineer[ed].” In this book and elsewhere you’ve identified scientism, the superficial and dishonest elevation of scientific inquiry as the sole avenue to truth. I do wonder sometimes about its subtler manifestations in our culture — do you think any of this ethos can be attributed to the cultural influence of modern science?

I don’t actually think that has much do with scientism. Probably people have always tried to plan their lives in some way to the extent that they can. I mean, who wouldn’t? But I do think the tendency has become hypertrophied among the contemporary upper-middle-class: the idea that life can be rendered predictable, reduced to an orderly succession of achievements that will guarantee security and comfort. Breaking students out of that mentality, getting them to understand that a successful life necessarily involves a degree of uncertainty and risk, as well as of serendipity and intuition, is one of the most important functions that colleges and mentors can perform.

6. This book is animated by the swelling social complaint that modern society has been corrupted by a technocratic “elite.” There’s much animosity emerging, most of it belated and justified, and it seems to be informing the population of the United States that their real enemy isn’t their liberal/conservative neighbor or even the feckless government, but the inordinately wealthy and powerful. This doesn’t comport very well, though, with one of the central lessons of literature, that of empathizing with whom you don’t understand or despise. You make an admirable appeal to readers from the American elite in your final chapter, “The Self-Overcoming of the Hereditary Meritocracy,” basically putting our biggest social problems at the feet of those who are most able to solve them but have the least incentive to do so. You speak of the empathic deficit in people like Enron’s Kenneth Lay; people seem to really hate him in a way similar, I imagine, to the way people hated Louis XVI or Marie Antoinette. But would we be that surprised if he turned out to be a complicated human being, like us all? How does one proceed with this conflict in mind?

6. This book is animated by the swelling social complaint that modern society has been corrupted by a technocratic “elite.” There’s much animosity emerging, most of it belated and justified, and it seems to be informing the population of the United States that their real enemy isn’t their liberal/conservative neighbor or even the feckless government, but the inordinately wealthy and powerful. This doesn’t comport very well, though, with one of the central lessons of literature, that of empathizing with whom you don’t understand or despise. You make an admirable appeal to readers from the American elite in your final chapter, “The Self-Overcoming of the Hereditary Meritocracy,” basically putting our biggest social problems at the feet of those who are most able to solve them but have the least incentive to do so. You speak of the empathic deficit in people like Enron’s Kenneth Lay; people seem to really hate him in a way similar, I imagine, to the way people hated Louis XVI or Marie Antoinette. But would we be that surprised if he turned out to be a complicated human being, like us all? How does one proceed with this conflict in mind?

I don’t agree that my argument sets up the conflict you suggest. In a sense, you’re echoing the “but I’m a good person” fallacy of liberalism. It isn’t about the personal attributes of the elite (I don’t know about Kenneth Lay, but George W. Bush is famous for being a swell guy in person), nor is it about denying their humanity. It’s about their structural position: the moral effects of their individual and collective actions within society, whatever their intentions might be. That’s why I’m not calling for the guillotine; I’m calling for increased taxation. A structural solution, not a personal one.