Time Out of Joint In Richard McGuire’s Here

“One learns about the characters the way a machine would, by analyzing discrete moments of their lives, like a search engine combing for patterns.”

In a well-known painting by the Belgian surrealist René Magritte, a miniature locomotive emerges from a dining-room fireplace as the smoke from its stack trails back under the mantelpiece. He called the work, completed in 1938, La durée poignardée, which translates literally to “ongoing time stabbed with a dagger.” (The painting is commonly known in English as Time Transfixed, a title Magritte never cared for.) “The image of a locomotive is immediately familiar,” Magritte wrote of the painting in a letter to an acquaintance. “Its mystery is not perceived. In order for its mystery to be evoked, another immediately familiar image without mystery—the image of a dining room fireplace—was joined.”

“Ongoing time stabbed with a dagger” could well describe the long-awaited new graphic novel Here by Richard McGuire, in which an ordinary plot of land in New Jersey is depicted at dozens of moments in time, from three billion years in the past to twenty-two thousand years in the future. The book is an expansion of a six-page comic of the same name, which McGuire drew in 1989 for an issue of Raw, the comics magazine published out of SoHo by graphic novelist Art Spiegelman, and editor Françoise Mouly.

A comic about a place, “Here” (1989) took its premise from a one-page strip called “A Short History of America,” which R. Crumb had published ten years earlier. In Crumb’s piece, Anytown, U.S.A., evolves over the course of a century from a bucolic pasture to a whistle-stop town to a twentieth-century strip mall. “Here” doesn’t have the satirical edge of “A Short History of America,” but it is more daring aesthetically; McGuire nests frames within frames and years within years, juxtaposing scenes that on their own would be banal, but when put together on a page are surprising and new. It was one of the first strips to explore the idea that a comic doesn’t need to tell its story chronologically. At the time, it “revolutionized the narrative possibilities of comic strips,” the graphic novelist Chris Ware wrote in Comic Art magazine. “Cézanne famously accomplished it with painting … and Richard McGuire, I think, did it with comics.” The strip was so influential, in fact, that twenty-five years later, reading his new book, McGuire’s technique feels almost conventional—a natural way to portray day-to-day life.

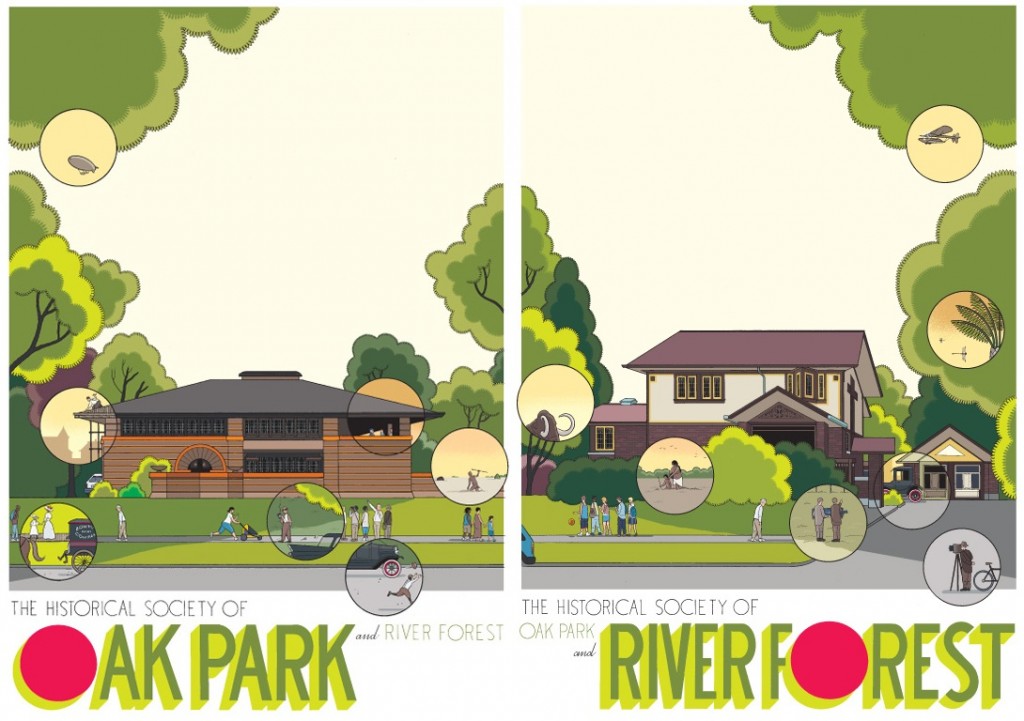

If, decades from now, a cartoonist is ever considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature, a likely candidate would be Chris Ware. Ware’s books include Jimmy Corrigan and Building Stories, both of which are about lonely losers living in Chicago. The emptiness and the drudgery of their lives are offset by layouts and color schemes that are obsessively, ecstatically detailed. Ware draws his cartoons with the clear-line style of Tintin and Gasoline Alley while packing his pages with information, sometimes jumping a century from one frame to the next. Ware acknowledged the influence the 1989 version of “Here” had on his 2012 poster for the Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest, Illinois, a work he dedicated to McGuire. It depicts a young Ernest Hemingway running to catch a football, Frank Lloyd Wright standing on the balcony of his Heurtley House, Robert McCormick flying overhead in a Sikorsky S-38, Potawatomi and Illiniwek Indians working outside, insects circling palm fronds from an antediluvian era. Ware wrote of McGuire’s “Here”: “I don’t think there’s another strip that’s had a greater effect on me or my comics.”

“Oak Park” and “River Forest” posters, Chris Ware. Courtesy The Historical Society of Oak Park and River Forest.

The graphic novel Here, like its precursor, is more poetry than prose, an attempt to capture within the narrow confines of a living room the chaos of the eons. It weaves the dramas of modern human life with those of geological history in a way that is not unlike Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life. But whereas Malick is ponderous (opening with an epigraph from Job), McGuire is playful (quoting pop songs like George and Ira Gershwin’s “Love Is Here to Stay”). The site on which everything takes place is like an improv stage. Characters from different periods come and go, unwittingly cracking one-liners about the events that are occurring years before or years after. One of the busier scenes in the book follows a fight between Benjamin Franklin and his son William about the future of the American colonies. The Proprietary House, where William Franklin lived as the last colonial governor of New Jersey, is a block down the street. The page is an aggregate of grievances occurring on top of one another, each labeled by year: floodwaters flowing through the window in 2111, a hole in the ceiling in 1949, broken glass on the carpet in 1963, and insults and put-downs from the Fifties through the Eighties.

A spread from the end of the book is more subdued: A Lenape Indian from 1620 is walking, bow in hand, across the same soil on which a construction worker, in 1907, is building a house. Inside, a woman from 1957 is wandering around the living room, and a radio, in 1968, is playing the Peggy Lee pop song “Is That All There Is?”

According to an interview in Comic Art, McGuire got the idea for the original “Here” when his roommate told him about the Windows operating system, which had been released only a few years earlier, in 1985. And indeed, the strip has the look of a busy computer screen. Revisiting the concept a quarter of a century later—when personal computers have become ubiquitous—McGuire goes even further, expanding the strip into a 300-page book. The result feels less like reading a novel than like killing time online or flipping through TV channels. One learns about the characters the way a machine would, by analyzing discrete moments of their lives, like a search engine combing for patterns. It could just as well be read back to front as it could front to back.

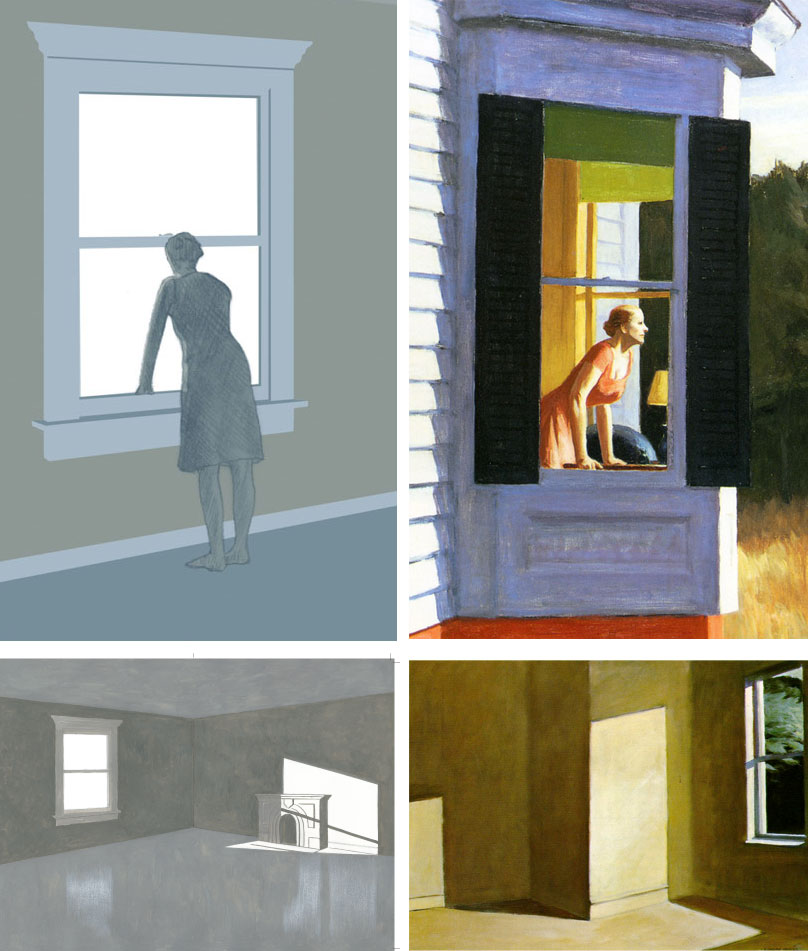

Writers made use of this kind of fragmentary storytelling in literature long before the time of the television or the computer. It’s the ambling fancy of the decadent brat epitomized by the character des Esseintes, in Huysmans’s novel Against Nature (1884), who holes up in his house in the country and gives himself over to the theater of his mind, to images and ideas instead of people and events. In Here, McGuire alludes to the despair and to the loneliness that are always lurking within such elaborate forms of distraction and escape. Two of the drabbest, grimmest spreads in the book are nods to studies of isolation and inertia by Edward Hopper that use single-family homes as their settings.

Clockwise from top left: Detail from Here (2014), Richard McGuire. Pantheon Books; Detail from “Cape Cod Morning,” Edward Hopper; “Sun in an Empty Room,” Edward Hopper; Here (2014), Richard McGuire. Pantheon Books.

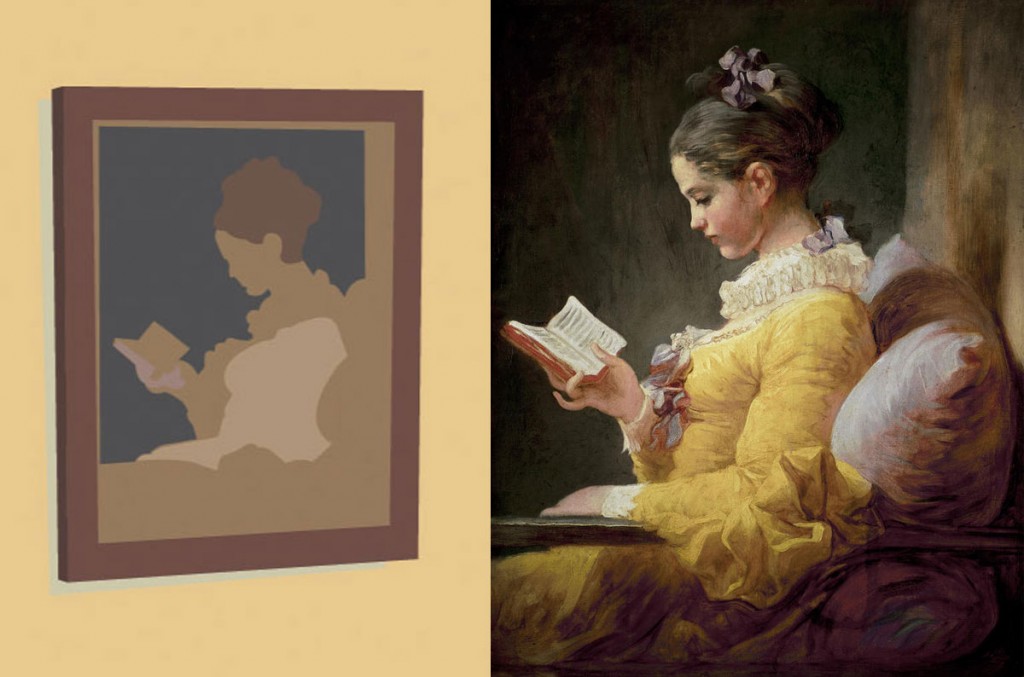

Hanging on the walls of the living room, in various eras, are posters or reproductions of paintings: two by Vermeer and one by Jean-Honoré Fragonard. All of them show girls who are reading alone, their heads tilted down as if they’re praying.

Left to right: Detail from Here (2014), Richard McGuire. Pantheon Books; “Young Girl Reading,” Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

The Peggy Lee pop song “Is That All There Is?” which appears in the book’s final scene, was inspired by Thomas Mann’s short story “Disillusionment.” It’s about an unhappy old man—possibly a caricature of Schopenhauer or of Nietzsche—who wanders around Venice muttering about how spoiled he was as a child, how high his expectations for life were, and how constantly disappointed he is with everything. Nothing he experiences—not even his parents’ house burning down—prevents him from asking if that’s all there is to life in a modern world. The way Here skips from one eon to the next makes it seem as though it’s asking the same question: Is this all there is to our past and future?

In “Mr. Natural’s 719th Meditation,” another R. Crumb progenitor of “Here,” a little sage with a long beard walks through a desert, unrolls a mat, and sits down to meditate. Suddenly, a highway is paved in front of him. As in “A Short History of America,” a strip mall pops up, and soon a cop is yelling at him to move. The sage, Mr. Natural, chants “Om,” and the buildings around him disintegrate, the winds of the desert blowing all the scraps and detritus away. Mr. Natural is then back in the unsullied desert. He snaps out of his trance, stretches, rolls up his mat, and walks whistling out of the frame.

Here might be what Mr. Natural sees as he escapes momentarily from the ordinary cycle of the days and the years. It’s life seen from the inside out rather than the outside in, and it’s indicative of the generation of cartoonists that Richard McGuire and Chris Ware belong to. Their comics are models of the mind, in which what was, what could’ve been, what is, and what might be are next to one another on the page, letting the reader, as Magritte claimed, perceive their otherwise invisible mystery.