Introducing the September Issue

William Deresiewicz discusses education in the age of neoliberalism, Andrew Cockburn argues that invasive species don’t deserve their bad reputations, Elaine Blair reviews Jonathan Franzen’s new novel, and more

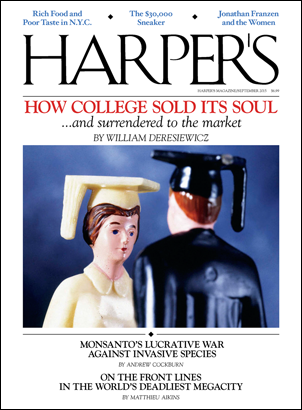

“The paramount obligation of a college is to develop in its students the ability to think clearly and independently, and the ability to live confidently, courageously, and hopefully.” This text appeared on banners scattered around the elite liberal-arts college where William Deresiewicz, the author of this month’s cover story, recently spent a semester teaching. Attributed to the college’s founder, the quote sums up what has long been understood as the mission of a liberal-arts education: to teach students how to think. And it is precisely this mission that Deresiewicz fears is being undermined in the age of neoliberalism, which, he writes, “reduces all values to money values.” The purpose of education today is to produce producers. As a result, the percentage of college students majoring in English, as well as the physical sciences, is dropping, while the percentage of those who graduate with degrees in vocational fields—business or communications—rises. “Learning for its own sake, curiosity for its own sake, ideas for their own sake”: these are the values now under attack at the very institutions where they should be nurtured.

The invasive species—what scourge of nature is easier to loathe? The tamarisk tree, a Eurasian interloper, has been accused of stealing water from native plants like the cottonwood. The zebra mussel, an immigrant from the Caspian Sea, is reviled for clogging water-intake pipes. And yet, in this month’s Letter from Washington, Andrew Cockburn argues that these so-called invaders don’t deserve their bad reputations: the tamarisk consumes no more water than the cottonwood, and the zebra mussel has successfully filtered pollution in Lake Erie. Perhaps, Cockburn suggests, the vilification of non-native fauna and flora has less to do with science and more to do with the fact that corporations—specifically Monsanto—make so much money manufacturing the chemical compounds meant to eradicate them.

A “tiny dish of salmon, black rye, and pickled cucumber . . . ‘inspired by immigrants’”; “Hudson Valley Moulard Duck Foie Gras ‘Pastrami’”; a “Finger Lakes Duck . . . [with] lavender flying out of its bum like a fragrant mauve comet.” These are just a few of the culinary delicacies to which Tanya Gold is subjected during her tour of New York’s most fashionable—which is to say most expensive—restaurants. She is aggressively coddled at Per Se, witness to the “transubstantiation of the turnip” at Eleven Madison Park, and “partially flayed” at Chef’s Table at Brooklyn Fare. She emerges—offended, outraged, injured—but with her dignity intact. Those who worship at the altar of the celebrity chef are not so lucky.

Elaine Blair, a thoughtful and evenhanded critic, finds much to admire in Jonathan Franzen’s latest novel, Purity. But this hardly prevents her from pointing out its flaws. “It is disappointing,” she writes, “that parts of Purity read as though Franzen urgently wanted to telegraph a message to anyone who would defend his fiction from charges of chauvinism: ‘No, you’ve got me wrong. I really am sexist.’” Though the younger women in Franzen’s book are, as Blair puts it, “admirably resilient,” the older female characters are far more vulnerable. The men, meanwhile, feel guilty for no longer desiring them. “It can feel melancholy, even shameful, to grow older while your ideal sexual objects stay young.”

Also in this issue: Matthieu Aikins on the gangster who tried to become a political contender in Karachi—one of the world’s deadliest cities—and paid a heavy price; Christine Smallwood on Claire Vaye Watkins’s new novel, Gold Fame Citrus; Rivka Galchen on the fifth season of Louie; Charles Bock on $30,000 sneakers; and portraits, by photographer Glenna Gordon, of the devout Muslim women in northern Nigeria who write romance novels.