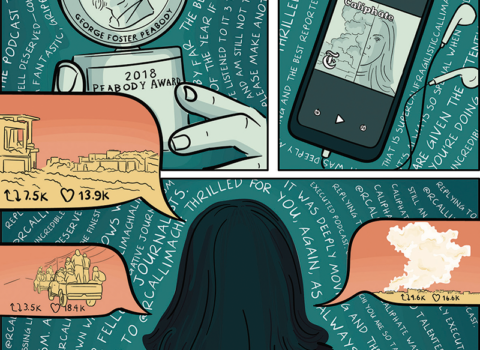

How the Islamic State Was Won

The Islamic State's influence grows; James Harkin interviews its fighters, enemies, and potential recruits

Published in the November 2014 issue of Harper’s Magazine, “How the Islamic State was Won,” examines the group’s rise through interviews with its fighters, enemies, and potential recruits. The story is free to read in full through November 23. Subscribe to Harper’s Magazine for instant access to our entire 165-year archive.

From a New York Times report, published November 18, 2015, on how the Islamic State’s influence in the Middle East grew after the United States withdrew from Iraq in 2011.

Beaten back by the American troop surge and Sunni tribal fighters, it was considered such a diminished threat that the bounty the United States put on one of its leaders had dropped from $5 million to $100,000. The group’s new chief was just 38 years old, a nearsighted cleric, not even a fighter, with little of the muscle of his predecessor, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the godfather of Iraq’s insurgency, killed by the American military five years earlier after a relentless hunt.

“Where is the Islamic State of Iraq you are talking about?” the Yemeni wife of one leader demanded, according to Iraqi police testimony. “We’re living in the desert!”

Yet now, four years later, the Islamic State is on a very different trajectory. It has wiped clean a 100-year-old colonial border in the Middle East, controlling millions of people in Iraq and Syria.

In the summer of 2012, as the initial demonstrations against Bashar al-Assad gave way to armed conflict between government and rebel troops, the Syrian army began pounding parts of its biggest cities with missiles and barrel bombs. The aim was to wipe out the regime’s armed opponents, but the result was to destroy the country’s social fabric and displace whole communities — leaving millions of Syrians with little to lose. Groups like the Nusra Front took control of towns across the north, and foreign jihadis flooded into Syria to join the fight. I’d seen them myself when I went to Aleppo in the spring of 2013. On the way into the city we were surrounded by countless shiny SUVs with tinted windows and black Islamist flags hanging off the back. At one point, as we waited in a traffic jam, a North African jihadi on the back of a truck fixed me with a stare and waved at me to put my camera down.

Now Nusra’s biggest rival for power in the north is the Islamic State — even though, until February 2014, ISIL was, like Nusra, an affiliate of Al Qaeda. But the marriage had always been uncomfortable. ISIL sprang from Al Qaeda in Iraq, which was led by a Jordanian named Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Zarqawi had angered Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda’s leadership by slaughtering Shias in Iraq. After Zarqawi’s death in a U.S. air strike in 2006, the group went into decline until a man named Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi took over, in 2010. Baghdadi started as a low-level street fighter during the American occupation of Iraq and is reported to have done some time in a U.S. Army prison. It was his decision to move the group into Syria’s stateless rebel areas in 2013 that changed its fortunes radically — and pushed its differences with Al Qaeda into the open. Al Qaeda’s aim had been to build a terror organization powerful enough to take the battle to its enemies in the West, but ISIL saw its mission as more religiously purist and more constructive — to improve the piety of Sunni Muslims and build a government around them. After ISIL began competing with the Nusra Front in Syria, Al Qaeda declared it was severing ties with the former.

In the first three months of this year ISIL fighters from Iraq and Chechnya fanned out over eastern Syria, annexing some of the country’s most lucrative oil fields as they went. They bought off local tribes and either massacred other rebels or demanded their loyalty. By the summer, the Islamic State was in control of 35 percent of Syria’s territory and was earning about $1 million a day in oil revenue. It used its newfound power to turn back to Iraq and take much of the northwest of the country.

Just as they’d done in Raqqa, the emissaries of the Islamic State in eastern Syria and in Iraq distributed services to citizens and charity to needy local families. Their protection, however, came with a social contract that brooked no dissent. An Islamic State edict in Raqqa reviving a medieval tax on non-Muslims came too late for the city’s Christians; most had already fled. Anyone ISIL deemed an apostate could be crucified or beheaded and left to rot in public thoroughfares as a warning to others. (In the Turkish city of Sanl?urfa I met a rebel militiaman who told me that his brother, a media activist, had been killed and his arms splayed in public crucifixion in Raqqa.)

By the time Al Qaeda cut its ties with ISIL, Baghdadi’s organization had already spectacularly renewed the franchise of militant Islamism around the world. From Tunisia to Gaza to Indonesia to Yemen, the wooden pronouncements of Al Qaeda’s Ayman al-Zawahiri were being passed over on new media for demonstrations of support for the Islamic State, and there were more and more sightings of its distinctive white-circle-on-black flag. Inspired by ISIL fighters’ black balaclavas and showy use of swords, some Syrians began to call them “the ninjas.”

Given the difficulty of reporting from Islamic State territory without being kidnapped — several Americans and Europeans are still being held hostage in Syria — journalists have had to rely on the group’s own media operation. The result was that a twenty-one-year-old student at Oxford University named Aymenn Tamimi became one of its most eloquent interpreters. Tamimi’s approach was to buddy up to ISIL fighters on Twitter and translate their statements; it made him enemies among other analysts, but it also paid dividends. Before I left for Turkey I went to Oxford to meet him. It was early June, and Tamimi was in the middle of taking his final exams; fidgety and wary of eye contact, in the gaps in our conversation he sneaked glances at his crib notes on Alexander the Great.

Tamimi’s assiduous translations of Islamic State propaganda were useful because they showed that these weren’t just monsters responsible for summary executions. They were also cutting down trees, organizing road repairs, securing electricity for their citizens, and protecting against theft. One rebel activist from Homs told me that all his friends in Raqqa loved the Islamic State, mainly because it took a firm line on price-gouging and criminality. “Even if the system is bad,” he said, “the fact that they have one is good.” In Raqqa, Tamimi said, the Islamic State has opened a consumer protection office dedicated to measuring the price and quality of anything sold in the city. One of its reports discusses the quality of service expected in local restaurants and the necessity of serving a decent kebab. Indoctrinating children into the Islamic State, Tamimi said, was central. “They’ve been doing it from day one. There is an understanding that not all the foreign fighters are going to stay in the long run, that the key is to have the next generation of Syrians.” In Raqqa the Islamic State inaugurated an office where orphans are registered and guaranteed material support. At its regular outreach meetings, children’s entertainment is a priority; one propaganda picture shows the Islamic State logo hovering atop a bouncy castle.

The sophistication of its output on Twitter and YouTube is surely one reason so many young foreigners have flocked to the Islamic State rather than to other jihadi brigades in Syria. Another, Tamimi said, lies in its ambitions to build a heaven here on earth. “A state gives you something to do, doesn’t it?” he said with a shrug.

Read the full story here.