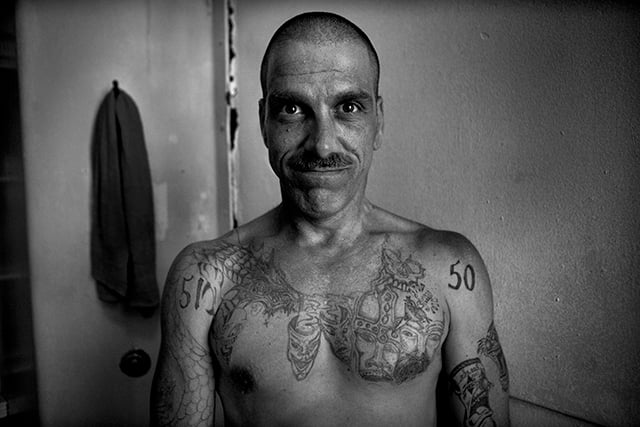

Eddie Tate showing some of his prison tattoos in the Old San Bruno County Jail, south of San Francisco, August 4, 2006. Photographs by the author.

On December 20th, I was in the Phoenix airport waiting on a flight home to Omaha, when I came across an article announcing the murder of a homeless couple in San Francisco’s Mission District. They were shot and killed near an encampment on the corner of 16th and Shotwell Streets. The victims, the paper said, were twenty-seven-year-old Lindsay McCollum and fifty-one-year-old Eddie Tate. I recognized Tate’s name. I had met him while photographing inmates at Old Bruno, the oldest of San Francisco’s jails. The jail closed in August of 2006, in part because Tate and five other prisoners filed a lawsuit alleging it was an overcrowded facility showing all of its seventy years, a place not fit to live or work in.

Tate moved to San Francisco after the 1989 earthquake, and since that time has gone by the nickname Tennessee. When I met him at Old Bruno, he was using the time in jail to get his high-school diploma. Tate had been clean for sixteen months, for the first time in as long as he could remember. He was a hyperactive infant and his dad put alcohol in his bottle to, as he later told me, “knock me out, to get me to go to sleep… and I’ve been on some substance or another my entire life.”

When I saw Tate again in 2011, he was locked up in the new San Francisco jail in San Bruno. A slightly built man with only a trace of an accent, Tate told me of his life growing up in rural Tennessee: “I was one of them that … lived so far up in the hills of Tennessee that I hardly ever got to go to school, and then when I went to school I was such a pain and everything that I’d make a straight F and they would pass me just to get rid of me. What education I got, I got through the prison system.” He summed up his strategy for doing time this way: “I have to be crazy to live the life that I live. I don’t want no misunderstanding, if you push I will get real crazy on you.” When I asked him about the tattoo on his shoulders that read 51-50, police code for a “danger to self or others,” he explained that “my part of the 51-50 is the ‘or others.’” Tate told me he was tired of doing time, and he was finished with the drugs. I did not see him again for a long time.

Tate playing a video game in his box, which was part of the homeless encampment at the corner of Harrison and Division, February 21, 2016

Afew years ago, I began running into Tate again while photographing on the streets of San Francisco. Our conversations were never long, but he seemed to have been good to his word: settled into a life outside of incarceration.

Then, in the run up to the February 2016 Super Bowl, the city forced the homeless living in tourist areas to move to less visible locations. Division Street, a long east-west street of small- and medium-sized businesses, became the go-to area for the city’s homeless population. It was there, on the corner of Harrison and Division Streets, that I saw Eddie again. He was living in a large wooden box with four wheels surrounded by an amazing amount of things: tools, bikes, and items of indeterminate use at that moment.

Tate could fix most things. He had tools and parts and was generous with his time and skills. He got by working on bikes, and was proud of the possessions he had acquired, including the wide-screen television on which he played video games. He was prouder still that he had stayed out of jail for four years—no small accomplishment for a homeless man with his rap sheet.

For most of February last year, I would stop by to chat. Then, in March, the city moved to clear the Division Street encampments. Tate was one of the last to go, and I lost track of him until October, when we ran into one another—again at Division and Harrison. He told me things were looking up. He had just scored some new clothes: a few pairs of pants, a shirt, and underwear. I gave him a couple of pairs of socks and asked where he was living. He said that a number of people were staying over by a grocery store about five blocks away on 14th Street and Shotwell. I told him I’d come visit.

Somehow I never did.

By late December, when I read of the murder of Tate and his partner, they must have moved at least once more, to 16th and Shotwell, where they were shot to death at around 8:45 p.m.

Looking through the images of Tate on the street I am reminded what he once told me. “I get along with everybody. I’m hyperactive so I’m always a worker somewhere.” As of now no motive or suspects have been arrested. Deaths like theirs, of homeless men and women on the San Francisco streets, are hardly unique. But I knew Eddie Tate a little, and I will miss him just as those that knew Lindsay McCollum will miss her.

Robert Gumpert photographed the homeless in San Francisco for the October 2016 issue of the magazine. View the photo essay here.