Inside the April Issue

Leslie Jamison on the Women's March, Alan Feuer on Bill de Blasio, Yascha Mounk on the refugee crisis in Germany, and Jessica Weisberg on Tokyo's exclusion of immigrants

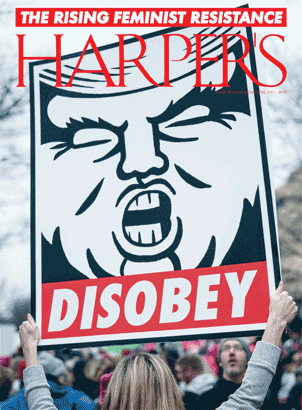

The Women’s March on Washington—a shot fired across the bow of the Trump Administration just a day after the dreary, depopulated inauguration—is now behind us. But for many participants, the memories linger. The size of the crowd, the jubilant camaraderie, the animal warmth of nearly half a million bodies: these are sensations that are not easily forgotten, and Leslie Jamison records them all in “The March on Everywhere.” It doesn’t matter that the marchers proceed in an omnidirectional chaos, or that nobody knows where the stage is. “I liked this lineage,” she writes, “this tradition of the partial and obstructed view: the marginal experience as authentic experience.” But Jamison moves beyond the event itself to explore the legacy of female activism. This is a historical question, of course, going back to the Suffrage Parade of 1913 and beyond. It is also, for the author, a personal one, since her mother’s long and ardent activism has tended to make her feel like a poseur, dodging meetings and declining to “lend [herself] to the humbler chorus of collective action.” Is democracy a matter of individual conscience or crowd behavior? Whitman argued that it was both: “One’s-Self I sing, a simple separate person, / Yet utter the word Democratic, the word En-Masse.” And in the end, so does Jamison.

The Women’s March on Washington—a shot fired across the bow of the Trump Administration just a day after the dreary, depopulated inauguration—is now behind us. But for many participants, the memories linger. The size of the crowd, the jubilant camaraderie, the animal warmth of nearly half a million bodies: these are sensations that are not easily forgotten, and Leslie Jamison records them all in “The March on Everywhere.” It doesn’t matter that the marchers proceed in an omnidirectional chaos, or that nobody knows where the stage is. “I liked this lineage,” she writes, “this tradition of the partial and obstructed view: the marginal experience as authentic experience.” But Jamison moves beyond the event itself to explore the legacy of female activism. This is a historical question, of course, going back to the Suffrage Parade of 1913 and beyond. It is also, for the author, a personal one, since her mother’s long and ardent activism has tended to make her feel like a poseur, dodging meetings and declining to “lend [herself] to the humbler chorus of collective action.” Is democracy a matter of individual conscience or crowd behavior? Whitman argued that it was both: “One’s-Self I sing, a simple separate person, / Yet utter the word Democratic, the word En-Masse.” And in the end, so does Jamison.

Elsewhere in the issue, two writers wrestle with the dilemmas of immigration. The Japanese, as Jessica Weisberg notes in “The Boy Without A Country,” have traditionally barred outsiders. Only about 2 percent of today’s Japanese residents are foreign-born—a tiny fraction for an industrialized nation—and this insularity has often mingled with an unsavory nativism. All of which has made life difficult for Utinan Won, the subject of Weisberg’s piece, who was born in Japan to a pair of undocumented parents from Thailand, and therefore stateless. In “Echt Deutsch,” Yascha Mounk explores a very different situation: an industrialized nation that has welcomed several hundred thousand refugees in 2016 alone. Germany’s altruistic approach has inspired many admirers around the world—and also such detractors as Donald Trump, who has called it a “catastrophic mistake.” But at home, it is still a work in progress. Angela Merkel has persuaded many of her fellow citizens that, as Mounk writes, the “country’s moral obligations can at times trump its self-interest.” How long she can sustain this tightrope act, especially as right-wing populism swamps much of Europe, is an open question.

New York City—or, more specifically, the city’s beleaguered and inadequate housing stock—is the subject of two more pieces. Alan Feuer takes a hard look at Mayor Bill de Blasio, who sailed into office on a tide of left-wing populism, then found that his campaign promises about affordable housing would necessitate a devil’s bargain with real-estate developers. “Defender of the Community” is not a hit piece. The author is more interested in the complicated collision of ideals and fiscal realities, which is by no means limited to the five boroughs. The photographer Samuel James, meanwhile, documents the “vast archipelago of steel and brick” that are the New York City Housing Authority projects, home to nearly 400,000 low-income residents. There are images of desolation here, not surprising amid the crowding, disrepair, and constant threat of violence. But there is also dignity, resilience, and the sort of high spirits that not even an indifferent bureaucracy or crumbling infrastructure can entirely crush.

In Readings, we have reminiscences of Jane, the underground railroad for reproductive care that flourished in Chicago during the 1960s, and a lengthy conversation about evicting a cat from a public library. Nat Segnit delivers a deliciously barbed piece of fiction, “Necessary Driving Skills,” and Reviews includes formidable pieces by Christine Smallwood (on Mary Gaitskill’s deconstruction of victim culture), Elaine Blair (on Mary McCarthy’s erotic heroes and villains), and Francine Prose (on Mohsin Hamid’s saga of displacement, Exit West). All that’s missing is a dose of the metaphysical jitters, and that, of course, can be satisfied by a quick perusal of Findings: “It now seems more likely that the universe is a hologram.”