I was at a Maryland travel plaza just off I-95 when I finally saw them, en masse and outfitted: the women. They were emerging from the fog like visions, their bodies spectral and streetlamp-lit, walking alone and with friends, with canes, with glowing cigarettes between their fingers; with boots over their jeans, with their daughters and mothers, with paper cups of coffee in their hands. They were headed into the rest stop, its vertical windows rising from the mist like church spires. They were holding doors for one another, asking, “Did I just cut you in line?” They were buying sodas and bananas. They were going to the bathroom. They were letting pregnant women go first. They were in utero, they were in wheelchairs, and they were all headed where I was headed: to the corner of 3rd Street and Independence Avenue.

When I arrived at that travel plaza — with my friends Rachel and Joe and their eleven-week-old baby, Luke — it felt like a mythical village of Amazon women had been transplanted from the jungle to the harsh fluorescent lighting of a highway rest stop. That night on I-95, arms full of licorice and chips, we didn’t yet know the statistics of our surge. There would be half a million people in Washington, three times the size of Donald Trump’s inaugural crowd, and more than 800 demonstrations on seven continents, with an estimated 4.2 million people marching in this country alone: probably the largest protest in American history. But already, we were made of nerves and excitement. We were buzzed on coffee. We were breastfeeding babies. We were part of a creature with 4 million faces. We were a bunch of strangers intoxicated by our shared purpose, which is to say: we were a we.

The D.C. Metro was jam-packed at eight the next morning. People were practically embracing strangers to make room for other strangers. Trump and Putin were French-kissing on five different pins. One hat said make racists afraid again. One pair of sneakers showed a uterus painted in pink glitter glue. The left foot said pussy. The right foot said power. A voice over the loudspeaker said: “Women’s-rights fighters from all over the world, welcome to your Red Line!”

We marched past the Capitol — which I barely recognized at first, because we were marching past the back — and then down to Independence. We did not need directions. We just followed the human stream. Our friend Erin, five months pregnant, put a sign around her neck that said feminist future, with an arrow pointing down at her belly. I saw a sign that said viva vulva. I saw a sign that said fight like a girl. I saw a sign that said i’m with her. It had arrows pointing everywhere.

A woman my age wore a sign that said fourth-generation feminist. It made me wonder who counted, whether feminists existed before the phrase itself was invented. My grandmother was raised on a farm in rural Saskatchewan, bathing once a week in kettle-heated water, and grew up to work in a university laboratory. She was one of the founding members of the Shattuck Neighborhood Action Coalition, in Oakland, California, a community where she put down roots decades before it started to gentrify. She led cleanup missions around Bushrod Park, collecting piles of garbage for trucks to haul away, and had everyone over afterward for soup and homemade bread. Until her diabetes made it impossible, she delivered voters-alliance newsletters to eighty homes in her neighborhood. She wore bright flowing skirts and we took walks together pretending to be aliens from the planet Algernon, trying to figure out the purposes of all these mysterious objects: garden hose, fire hydrant, wind chime. She believed in the latent magic of the proximate, and in community as something actively built, not passively inherited. She put her body and her time — her self — into work she felt was important.

As for my own mom, I have always understood her commitment to social justice in worshipful, often cinematic terms. She fell in love with her first husband while they were protesting the Vietnam War in Portland, Oregon, at a liberal-arts college where the students figured out ways to make their sex lives count toward the P.E. requirement. At one demonstration in San Francisco, where federal agents started photographing the crowd from nearby buildings, she and everyone held up their driver’s licenses.

I grew up hearing stories about the season she spent picking crops in the south of France, with the woman I eventually realized had been her lover — which only made these tales more intoxicating, their days spent harvesting olives and Roma tomatoes, staying in a small cottage in the woods, getting paid in jugs of wine, stacking the fireplace with roots at night and watching their knotted, whirling patterns burn. My mom told me about a strike she had led among the olive pickers, who were forced to work long hours in the brutal cold wearing only cotton socks as gloves.

As I saw it, my mother had repeatedly shown up for something larger than her own life. She’d been desperate to join the Peace Corps. She worked as a precinct leader for the McGovern campaign, in 1972, while she was pregnant with my oldest brother. (She called him George while he was still in the womb.) She brought my brothers, just five and six years old, to rural Brazil when she was doing her doctoral research on infant malnutrition. She spent decades working on maternal-health research and advocacy in West Africa, and I carried in my mind’s eye a vivid memory that wasn’t mine: the night in Togo when she accompanied a woman in obstructed labor to the hospital in Sokodé, driving along muddy, rutted roads while the rain pelted down.

It wasn’t just the things she had done that I admired but the spirit in which I imagined her doing them: selflessly, putting her own comfort aside, choosing the path of most resistance. Her life in social justice was always intertwined with her life as a primary parent. She was committed to her children — and to children who weren’t her children.

In her early seventies now, she is still at it. As a deacon in the Episcopal Church, she recently protested unjust immigration policies by giving communion through the mesh of the border fence in Tijuana. She was also arrested with unionized hotel workers in downtown Los Angeles, wearing her clerical collar as she was handcuffed. As I construct the story of her life, it shimmers with valor, with purity of motivation, and with endless, altruistic work.

I have always found a kind of mission statement in the story of her very first protest, a march around Portland’s Pioneer Courthouse Square against the House Un-American Activities Committee. My mom was handing out flyers, and one woman handed hers back, looked my mom straight in the eye, and said, “I hope your children grow up to hate you.” It was a female curse, a way of saying: I hope the gods of motherhood punish you. But ever since my mother told me that story, I have believed that loving her as much as I do is a political act.

I have also seen myself as a disappointing inheritor of her legacy. My own commitment to social action — while durable — has felt more like a series of do-gooder missteps and awkward incursions into activism: mixing concrete (badly) in a small Costa Rican village to build a footpath to the local church, as a naïvely well-intentioned fifteen-year-old whose parents could afford to fund her exercises in conscience; or tutoring mothers in a minimum-security prison to help them pass their G.E.D. exams, feeling so shy — so convinced I was doing a terrible job — that my stomach knotted up with anxiety.

My attempts at direct political action have been shot through with apathy and bumbling. When I canvass, there is the perpetual nervousness before each buzzer-ring, and an ongoing record of startling ineloquence. (“I’m not voting.” “But you should!”) My days organizing with my graduate-student union always felt grudging and full of discomfort: town hall meetings I didn’t want to attend, follow-up emails I didn’t want to type.

Whenever I compared my history of social engagement with my mother’s, it felt meager and disheveled. I was a lurker, always ducking around the edges of the crowd, hovering near the snack table, drinking too much coffee. I was both too insecure and too egotistical to fully join group efforts, convinced I had better ways to spend my time than being one body among many. I was too obsessed with singular expression, with my own voice, to lend myself to the humbler chorus of collective action. This was the ego investment — the stubborn sense of my own identity — that kept me from being useful, from being subsumed into the whole.

When we got close to Independence and 3rd Street, and found no stage in sight, we wondered: Are we in the right place? We were definitely someplace, with more people than I’d ever seen in my life. Every time we looked down a street, we saw endless bodies. We were looking for the core of it: the epicenter of the gathering, the departure point. Eventually we realized we were marching toward the wrong side of the stage, along with probably 20,000 other people. I hadn’t imagined the rally like this, with this abiding uncertainty about where the thing itself was.

We inched up C Street to see if we could hit Independence further back. We walked over hay and flattened horseshit, perhaps left over from the inaugural parade, though we weren’t directly on its route. We passed circular black tanks labeled horse control. A woman stood in the back of a pickup truck hawking get your hands off my vajayjay pins at the top of her lungs. A few blocks away, bras dangled from the trees. A woman dressed in bright orange was looking for a group of other women dressed in bright orange.

The buildings of our government felt vast and indifferent on either side of us, made of cold pale marble. We flooded their inhuman scale with our human bodies. The crowd often stopped in its tracks, because there were so many of us and because so many of us were taking selfies. This did not seem like vanity so much as a useful motivating impulse, the desire to say: I was part of this. We all wanted our presence documented. If activism had to be entirely selfless — no affective payoff, no emotional or digital souvenirs — it would never happen at all.

For the first few hours, I couldn’t hear or see the rally. Gloria Steinem was speaking somewhere, but at a certain point I couldn’t have even told you which direction the stage was in. I tried to check on my phone, but I wasn’t getting reception. No one was. There were too many of us. Our technology was blocked by the more ancient technology of so many bodies gathering together.

We weren’t on the official route of anything. We weren’t even sure where we were going. But this didn’t mean we weren’t at the march. We were the march — in our mistakes and our rerouting, in our circling back, trying again, taking the long way around. We were already part of what we had been searching for.

When Alice Walker arrived home from the March on Washington in 1963 after taking a night bus back to Boston, her relatives were sure they’d seen her on TV. They insisted they had spotted her “among those milling about just to the left of Martin Luther King Jr.” But they had seen what they wanted to see. She wasn’t anywhere near him. “The crowds would not allow it,” she wrote later. “I was, instead, perched on the limb of a tree far from the Lincoln Memorial.”

I liked this lineage, this tradition of the partial and obstructed view: the marginal experience as authentic experience. It was permissive. You felt what you felt. You saw what you saw. You took what you could get. The only thing you could say for sure was that you had shown up.

At the Women’s March, I saw people perched in the trees all around me, straining to hear. I thought of their aching legs and wondered how long they would last up there. I wondered if they had remembered to bring snacks.

Activism isn’t an oil painting. It’s real life: a box of tampons, a forgotten cell-phone charger, a late-night car ride. It’s many hours standing on concrete. It’s not just the glorious surge, or the giddy feeling in your stomach when you’re on the move, tucked into the thick of the crowd, voice hoarse from shouting. It’s also everything it takes to get there. It’s dealing with the low-tire-pressure indicator light, flat on your stomach in a Bed-Stuy parking lot, losing the little metal cap somewhere on the oil-pocked asphalt. It’s getting stuck in bumper-to-bumper on the Verrazano, with barges chugging through the gloom below. It’s a post-quesadilla stomachache in Jersey. It’s changing the baby in the back seat because the changing table in the restaurant bathroom is covered in mouse shit.

There is no activism that isn’t full of logistics and resentments and boring details. Commitment to anything larger than your own life often looks mythic in retrospect. But on the ground, it’s all inbox pileup and childcare guilt; it’s a lot of wondering if you’re having the right feelings or the wrong ones, or confusion about which is which. It’s messy and chaotic and imperfect — which isn’t the flaw of it but the glory of it. It trades the perfect for the necessary, for the something, for the beginning and the spark.

My mother may have led olive pickers on a strike in France, or been cursed out by an angry housewife in Pioneer Square, but her life isn’t myth. It’s a life. Over the years, I’ve learned the counter-history of whatever glorious legend I wrote for her — not its cancellation, but its supplement: the fuller version. Her life in activism was fraught with apathy, despair, an urgent sense of inadequacy.

In other words, it was full of humanity. There were other truths, other parts of the story. She couldn’t fulfill her Peace Corps assignment because her marriage fell apart and she wasn’t allowed to report to Botswana without her husband. After the first flush of her antiwar activism, she fell away from the movement and into depression. She was working as a telephone operator in Oakland, trying to connect calls across the Pacific, hearing wives and mothers crying as they failed to reach soldiers they hadn’t heard from in months.

The whole arc of her story was punctuated by moments of doubt and disillusionment. When McGovern was crushed in a landslide, losing every state but Massachusetts, she felt as though she had been personally rejected by her country. Her career in public health didn’t grow seamlessly or instantaneously from her days of early motherhood; it took her years to figure out that she didn’t want to spend two decades at home caring for her children. She almost dropped out of grad school on her first day because she was afraid it would take her too fully away from her sons. In retrospect, she felt guilty about bringing them to Brazil, especially my middle brother, who didn’t like his preschool and had trouble learning the language.

Not long ago, she met a Vietnam vet who had also become an Episcopal deacon, and she told him about heckling a train of returning soldiers, how much she’d always regretted doing it. She told him that she was sorry. He said she was the first person who had ever apologized to him for doing that.

My mother recently confessed to me that she had never liked canvassing. This was years after I’d written an internal script that imagined her knocking on doors with full-throated eloquence and confidence, the way I never could. She didn’t knock on doors because she enjoyed it, she told me, or even because she felt she was good at it. She did it because it was the work that needed to be done.

The point of participating in large-scale collective action isn’t glory. It’s something close to the opposite: being a body among bodies. It’s about submerging yourself, becoming part of something too large to see the edges of. Over chiles rellenos in South Jersey, at a strip-mall Mexican restaurant on our drive down, Rachel told me: “My goal is just to be a body in Washington.”

We were bodies among bodies. We were with an old man with a silver beard and a green vest and a sign around his neck that said this is what a feminist looks like. Feminists looked like many things. A woman in a coat covered with tissue-paper flowers had a sign that said frida choose. Another woman was dressed up like a giant vagina, with plumes of purple and beige felt. We had our tampons and our cigarettes and our breast pumps. We were ready to rewrite Mailer’s Armies of the Night. We wore American flags as miniskirts, as bandannas, as hijabs. The transparent backpacks mandated by the organizers showed Luna bars and sunflower seeds: the comet trails of preparation behind everybody’s presence. You saw the internal organs of cell phones and city maps, little confessions strapped to everyone’s backs. A first-time protester told me she brought home-made cookies, but noticed that the veterans brought throat lozenges.

I felt awkward chanting — I often do — but chanted anyway. If everyone felt too self-conscious to chant, then we would make no noise at all. I wanted to reframe my own awkwardness as part of the process going right, or getting started, rather than a sign that it had always been going wrong. I wanted to believe that submission to awkwardness is one of the ways you can show up for a cause. Awkwardness can be part of authentic presence, the same way doubt is part of faith. One guy’s sign said i hate crowds, but i hate trump more. Another said so bad even introverts are out.

We passed a cluster of pro-life women standing on a traffic island. One held up a rosary and a poster of a dead baby. The baby in the photograph — the idea of the dead baby, the visual rhetoric of shame-mongering — was less real to me than the baby my friend was pushing in his stroller: the child of a pro-choice mother, surrounded by the children of pro-choice mothers. The women on the island held posters that said women do regret abortions.

Did we? Speaking for myself, I knew I was grateful that I’d been able to make a choice, that I hadn’t had to drive thirty-six hours across state lines or feel a wire inside my body. I couldn’t speak for the thousands of women around me who had also gotten abortions. Perhaps some regretted them. They still had the right to get them. I could see one poster showing a crude clothes hanger drawn next to the scrawled words never again.

I saw more uteruses that Saturday than I had ever seen before, more than I’ll ever see again. I saw them painted on cardboard and scribbled on paper. I saw them in handcuffs. I saw them made of snakes. I realized I had never known whether the plural of uterus was uteruses or uteri — and the question had never felt more urgent. One sign said there’s an elephant in the womb and featured a little G.O.P. mascot lurking at the top of a fallopian tube. Our mascots were the ovaries, the Statue of Liberty, and the pussy cat.

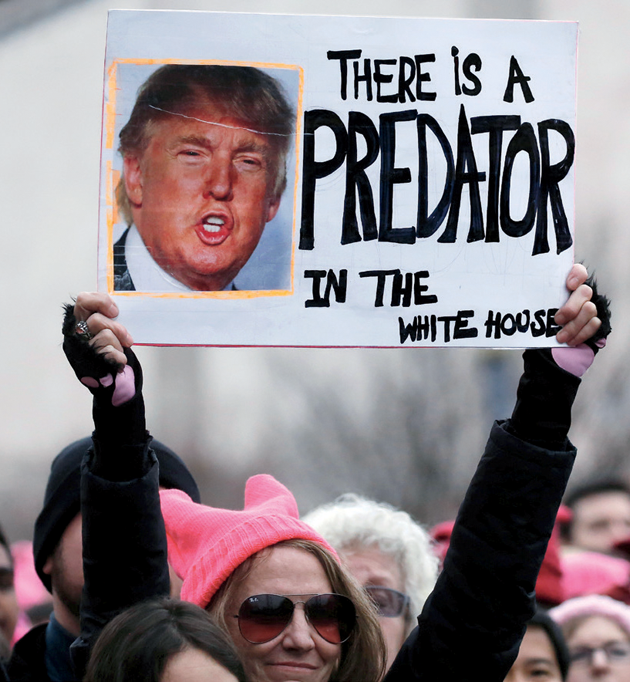

I’d always thought signs were for external eyes: for the media, or for the president I imagined peering down at us from the Truman Balcony. During the march, I realized that the posters were also for us, a way to keep from getting bored. When you’re standing on concrete with no cell reception and thousands of bodies packed all around you, and the crowd hasn’t moved for hours and you’re not sure if it’s ever going to move again, the signs are a saving grace: a live-action Twitter feed with its own endless taxonomy.

There were the anatomy signs, internal organs made external and external organs on parade. pussy grabs back was its own genre, its own little zoo: vagina dentata, fluffy kitten, big cat baring its teeth. There were the grandma signs, like ninety, nasty, and not giving up. Or the elderly Japanese woman with a sign sticking up from the back of her wheelchair: locked up by us prez 1942–1946 never again. One woman’s cross-stitch read i’m so angry i stitched this just so i could stab something 3,000 times. The Trump signs were endless. One showed the president grabbing the Statue of Liberty between her legs, creasing the folds of her robe. Another told the straight truth: you ruined home alone 2. I thought of the public service performed by that sign, how many people it must have made smile over the course of an hour, a morning, a day.

Our signs were joyous. We were united. We were glorious. We were uteri. We were a crowd-sourced poem! A scrolling song!

A group of men standing outside the National Museum of African American History and Culture held up a sign that asked who else will you march for?

At the Women’s March, our “we” was not uncomplicated. I never wanted to pretend it was. “Community must not mean a shedding of our differences,” said the writer and activist Audre Lorde in 1984, “nor the pathetic pretense that these differences do not exist.” Her belief in difference as a creative force felt like the right kind of optimism for this moment, full of faith that did not depend on naïveté.

Feminism, after all, had evolved by way of self-critique. There were the first-wave suffragists, who abandoned the prospect of cross-racial solidarity when it threatened their campaign, followed by the second-wave feminists of the 1960s and 1970s, who fought internalized patriarchy in consciousness-raising groups and crusaded for reproductive rights and economic equality. They were followed in turn by the third wave, who criticized the second as myopically attuned to the struggles of privileged white women. From its inception, the Women’s March offered itself as a vexed and imperfect manifestation of the third wave — not its resolution or consummation, but a continuation of its necessary reckonings.

By now its creation myth has become familiar: two women posting on Facebook just after Trump’s election. In New York City, Bob Bland proposed a Million Pussy March. In Hawaii, Teresa Shook put out a call to organize a women’s march just after the inauguration. She went to bed with forty replies, and woke up to 10,000.

By the end of that week, Bland had responded to the criticism leveled at the prospect of a Women’s March led by two white women. She invited three women of color to take the helm, all prominent organizers: Tamika Mallory, a civil-rights gun-violence activist; Carmen Perez, a prison-reform advocate focused on incarcerated youth; and Linda Sarsour, a Palestinian-American racial-justice advocate and mother of three, who had successfully campaigned for New York City’s public schools to designate two of Islam’s holy days as holidays. In their official platform, released a week before the march, these organizers purposefully highlighted certain issues — racial injustice, mass incarceration, police accountability, the persecution of undocumented migrants — that moved pointedly beyond the standard second-wave fare of reproductive rights and equal pay.

Nearly two weeks before the march, the New York Times ran a front-page story quoting a white woman from South Carolina who had decided to cancel her trip to D.C. because she had been offended by a Facebook post from a black volunteer advising “white allies” to listen more and talk less. She said it made her feel unwelcome. “This is a women’s march,” she said. “We’re supposed to be allies in equal pay, marriage, adoption. Why is it now about, ‘White women don’t understand black women’?”

Feminism has always been about white women not understanding black women. But at its best, it has also been about women recognizing the shifting contours of their own ignorance, and trying to listen harder. That awareness of limited knowledge and past mistakes can be a source of strength, rather than the movement’s shameful underbelly.

Decades ago, Audre Lorde told white feminists who were offended by her outrage: “I cannot hide my anger to spare you guilt, nor hurt feelings.” She wanted shared oppression to enable vision rather than obstruct it. She wanted women to recognize what wasn’t shared, to fight the perils of conflation, to acknowledge their own complicity. “What woman here is so enamored of her own oppression,” she wondered, “that she cannot see her heel print upon another woman’s face?” This felt just as relevant three decades later. The trick was seeing the patriarchal footprints everywhere, even under our own feet. Intersectional feminism wasn’t just an abstraction, and it wasn’t about getting paralyzed by the shame of privilege. It was about owning it. When my mom led the olive pickers on strike, she was aware that she could afford to lose her job more easily than most of them, that she could afford the risk.

I wanted to send every white woman offended by the Women’s March a copy of Sister Outsider, with a bookmark tucked into Lorde’s observations about the role of guilt in the feminist community. “All too often, guilt is just another name for impotence, for defensiveness,” she wrote. But this guilt, if it led to change, could become useful as the “beginning of knowledge.”

At the Women’s March, a black woman carried a sign that said white women voted for trump. A white woman carried a sign that said white women voted for trump. When Jasiri X, a rapper I’d never heard of, came onstage, he said, “My mother raised me all by herself. . . . As a man, I can never understand how she felt.” He said: “Fuck white supremacy, white privilege, and white wealth.” I could not see the woman in the pussy hat beside him, translating his message into sign language, but I could hear his words through the speakers. I felt implicated. I was implicated. My discomfort was the point: my discomfort and everyone’s. There was something useful in gathering to feel powerfully uncomfortable together, rather than simply celebrating our numbers. Humility was as important as solidarity. Jasiri X admitted that too: “I can never understand how she felt.”

When I attended my first Black Lives Matter march, in Portland, I felt uncomfortable. Was I wanted? Was I intruding? I stayed quiet and followed in the footsteps of others. But I’m glad I was there. My discomfort wasn’t particularly profound. It was just a small down payment against the kind of collectivity I believed in — a collectivity in which we weren’t cloistered by the silos of our backgrounds, but still didn’t assume that solidarity would be easy, that its declaration would mean it had been fully realized.

At the Women’s March, the leadership was largely women of color, but the attendance wasn’t diverse. I could see this for myself, and during the weeks that followed, other women testified to it as well. “Simply put,” a woman named Brittany Martinez told me, “the march was very white.” Brittany explicitly identifies herself as a queer feminist of color, to distinguish herself from the “pervasive and popular brand of default white feminism.” At the Women’s March, certain celebratory totems — like the vaginas everywhere — made her uneasy. “First,” she told me, “all the ‘pussies’ were pink, which doesn’t reflect what many vaginas look like for women of color.” Because “women of color are hypersexualized by popular culture in ways that white women are not,” she found that “putting so much emphasis on ‘pussies’ felt uncomfortable.” Her observations made me aware of my own blind spots, which felt less like an argument against the possibility of solidarity and more like another argument for trying to understand how much I didn’t understand.

When we chanted “Black Lives Matter!” on Constitution Avenue, I could feel our whiteness so acutely, the pale average of our collected bodies. I thought of the Suffrage Parade of 1913, our inspiring but deeply tainted lineage: a march led by a white woman on a white horse, with columns of black women in the back. white silence is violence, said one sign, twenty signs, a thousand signs. But a thousand white people holding signs saying white silence is violence didn’t mean the violence was over.

We hit the central vein, the jugular of the rally, at 7th Street. Catching sight of a Jumbotron felt like arrival. The National Mall was a sea of bodies with the Smithsonian Castle rising behind them, all red brick and turrets, iconic and occupied. Our crowd was articulated by dabs of pink, not homogeneous but shaded into hues — rose, salmon, watermelon, lemonade, bubblegum, fuchsia — and broken by rainbows and parkas.

We found a spot where we could see the screen but couldn’t hear anything. Then we found a spot where we could hear the speeches but couldn’t see anything. It felt so right to have the event blocked by the other bodies watching the event: they were the event. Somewhere out there, on a stage I’d never see, Gloria Steinem uttered the words I would read online the next day: “I wish you could see yourselves. It’s like an ocean.”

From the middle of the ocean, we couldn’t see the ocean. But we could see one another’s faces, squinting and hungry. My friend Heather had written to me beforehand, “I’ll be somewhere in that sea of women, looking for a bathroom.” I thought of her frequently, and it became a kind of mantra: Heather was out there somewhere, looking for a bathroom. It was a reminder that our collectivity was powerfully visceral: we were bodies that needed to eat and pee.

A union leader stood in front of our endless columns and addressed Trump directly. “I don’t know what kind of president you’ll be,” he said, “but you’re a hell of an organizer.”

As I looked over that sea of bodies, I kept feeling the urge to specify them. I wanted them not in their plenitude but in their particularity, their fine-grained humanity. So I spent the weeks following the march talking to other women who had been there. Almost every woman described the sheer mass of the crowds as the defining part of her experience. Monica Melton found herself moved by the blunt force of accumulated body heat. “In the thickest part of the crowd,” she said, “it was literally hot.”

Anika Rahman, who had fled the Bangladeshi War of Independence and was marching with Amani, her thirteen-year-old daughter, realized at a certain point that there was “no correct route.” Which meant that every route was the correct route. She told me she was marching to resist an administration that threatened every part of her identity, every part of her life’s work: “I’m brown, I’m an immigrant, I’m a woman, I’m a Muslim.” After coming to the United States at the age of eighteen, she obtained a law degree, devoted herself to fighting for human rights and social justice, and watched the rising tide of anti-Islamic sentiment in her adopted country. She also raised Amani, who wanted to be president and was carrying a banner that said rise against the predator in chief, her arms aching from its weight.

Nadia Hussain was also deeply moved by all those bodies in the streets. She was brought to tears when Michael Moore called on the crowds to fill the George Washington Bridge if that was what it took to stop the deportations. Nadia had grown up the daughter of Bangladeshi immigrants, spending much of her childhood in public housing, one of the only kids of color in her high school. She married a Salvadoran man whose mother had brought him across the border at the age of five; he became a U.S. Marine, and they were raising a twenty-two-month-old Muslim Latino son. Nadia knew it was important not just to show up for the march but also for the work that would need to be done every day after it. She wanted to keep putting her body on the line. “That’s why we remember the civil-rights movement,” she told me. “They put their bodies on the line.”

Amy Lewis, a mother of two and therapist from Pittsburgh, wanted to put her body on the line as well. “I wanted to break through the paralysis of racial shame I’ve grown up with,” she told me, which came from “the privilege of our white skin.” She still remembers the thrill of her first protest, taking the bus with her mother to a feminist rally in downtown Pittsburgh. “I was small and exhilarated,” she recalled, “looking up past the faces of the adults surrounding me, to the tops of the office buildings I thought of as skyscrapers, and beyond to the night sky, feeling strangely safe in the loud crowd.”

When Amy brought her own twelve-year-old daughter to D.C., she felt protective. The most extreme bodily sensations she remembered were sensations of vigilance: “The strain of constantly watching for exit points, assessing the danger when we were on a bridge or in a contained space, amplified enormously by my concern for my kid.” She described her initial response to the sheer volume of the crowd as one of panic: thoughts sluggish, limbs heavy, words slow and disorganized. She was supposed to meet her mother but started to panic when she realized that it might not be possible. Cell phones weren’t working. The route on the map was jammed with thousands of strangers. When Amy finally made her way to their meeting point, via side streets and force of will, and found her mother waiting there, she felt “strong” and “complete.” She said, “The sludge in my veins turned liquid, I felt cheerful, and we looked around with excitement and wonder as we walked into the thick of the crowd.”

The physical act of marching wasn’t simple. The plain truth was this: the Mall was packed all the way back to the Washington Monument. The march couldn’t happen because the route was already occupied by half a million bodies. “When the word moved through the crowd that we had filled the entire route, we roared,” Amy told me. “The irony of such numbers equaling physical paralysis struck us. We were many, we were powerful, we were unable to move.” At one point, a rumor spread that the march was being canceled, a victim of its own success, but Tamika Mallory came over the speakers to assure us that it wasn’t so. We were going to take Constitution Avenue all the way to the Ellipse.

Of course I didn’t end up on the correct route. As Anika pointed out, there was no correct route. I ended up somewhere else — on Independence, I think, up to 14th Street, then left on Constitution up to 17th. The truth is, I can only tell you where I marched because I looked it up afterward. While I was marching, it was more like a dream, with no street signs or Google Maps. I was just following the flow of bodies. I was noticing how little trash there was on the streets, and how much glitter. I was listening to an old black man shout, “Mike Pence has got to go!” as he sold photographs of the Obama family to weeping white people.

Each time the march was stopped, which was often, I imagined the traffic had gotten clogged because of courteous marchers ceding the intersection to one another, manners manifest as gridlock: “You first!” “No, you!”

In the shadow of the Washington Monument, my friend Joe said that for the first time since the election, he was excited to read the news. We were helping to write the story we wanted to live. But we would need to read about it afterward, to understand what we had been part of.

Leaving the march, we passed hundreds of signs piled against a fence on Pennsylvania Avenue. They didn’t look discarded. They looked defiant. Joe and Rachel changed Luke’s diaper on a cold marble bench at the Ellipse Visitor Pavilion. We passed weary protesters resting on the bleachers that had been empty for Trump’s inauguration parade. It felt good to think of them serving this purpose. We needed to rest, because we weren’t done. It wasn’t just Washington, and it wasn’t over. It was everywhere. It was ongoing. It was people singing with candles in the Budapest night, spilling through the streets of Atlanta, Oakland, Jackson, and Macau. It was people in Calcutta wearing sandals in the sunlight and holding a banner that said resistance is fertile. It was people in Fairbanks marching in full winter parkas under tree branches covered in snow, with the temperature nearly twenty degrees below zero, a girl in red ski pants, maybe eleven or twelve, holding up her own sign: i survived cancer. trump made me uninsurable.

My husband spent two and a half years fighting insurance companies while his first wife battled a complicated form of leukemia — the disease she died of. When she was diagnosed, their baby was six months old. Eight years later, that baby held a love trumps hate sign on a cold afternoon in Prospect Park. Which is all to say that this election is personal for everyone. Day One of the new administration was personal for everyone. Also true: It’s been personal for years. It’s been personal for centuries.

A woman named Aditi Khorana later told me about crying jags after the election, feeling her lifelong sense of marginalization — as a woman of color, as the daughter of Indian immigrants — sharpening into almost unbearable acuity. Why did this country hate her so much?

Aditi loved watching the march flood her city: the Los Angeles subways were packed instead of empty, Pershing Square turned into an ocean. She lives just a few blocks from the knitting shop where the pussy hat was first conceived. When the conductor announced that they were rerouting her train that morning, because everyone on it was headed to the same place downtown, all the passengers started cheering. “It felt like a tiny victory,” Aditi said. “Like you’ve got to accommodate the will of the masses.”

She had begun her adult life in the aftermath of George W. Bush’s election, and under the shadow of his wars. She protested the invasion of Iraq as often as she could, with “this sense that the world we were inheriting was being created by old, rich, white men for themselves and their kids.” After Obama was elected, she felt safer, which enabled her to turn inward, toward her own life and career.

Trump’s election brought Aditi back to the streets. She felt proud to share the Women’s March with her parents, who had told her stories about living under Indira Gandhi’s autocratic regime, and had committed their lives to fighting for the oppressed: her mother as a sociologist, her father at UNICEF. Trump’s victory hit them “on all levels,” she said — as immigrants, people of color, parents who had raised two daughters.

She was struck by the kindness people showed them that day: giving up subway seats, catching her mother’s arm when the train lurched. Her mother said the march felt like a collective exhalation. Sikhs passed out bowls of chana and reminded Aditi of her grandmother, a Sikh, who had passed away years before. Afterward, she and her parents went to one of their favorite spots in the city — a hole-in-the-wall run by a Mexican couple — and had Cokes and ceviche. It felt good to support an immigrant business, Aditi said, and it felt good to see her elderly parents “light up with excitement as they spoke about the resistance.”

What does feminist inheritance mean? For Amy, it meant going to a Chicago Seven protest in utero, and then finding her mother, decades later, amid thousands-strong throngs of women in D.C. For Vaeme Tambour, a former Hillary campaign staffer, it meant going to the march with the women in her family — ages sixteen to ninety-three — and walking in a tight circle around her great aunt, who marched with a walker, to protect her. For Laurie Logan, a family physician and lesbian mother from La Crosse, Wisconsin, it meant marching on Washington with her teenage daughter, Annie — full of maternal guilt because she hadn’t brought enough water or snacks — as the continuation of a lineage that began when she was young. She’d grown up with little sense of separation between politics and the rhythms of daily life. “I have clear memories of conversations about political issues being mixed with ordinary life,” she told me, “my mother ironing and talking about the Prague Spring and our right to free speech and a free press, drying dishes while talking about the importance of legal abortion.” Laurie learned her first chant at the age of four: Humphrey, Humphrey, he’s our man! Nixon belongs in the garbage can! As for Annie, she had grown up looking at pictures of her mother marching at rallies — and in D.C., she finally got to march beside her.

But feminist lineage isn’t always a simple inheritance. Brittany, who marched in New York, told me that the second time she ever protested — at a demonstration supporting H.I.V. education, when she was in high school — she was arrested in front of the White House for civil disobedience. Her father, who had been the president of his local NAACP youth chapter and a 1960s civil-rights activist, was proud. He said activism ran in her blood. But her mother was furious.

Andrea Chen, a second-generation Chinese-American raised in Queens, told me her mother disapproved when she found out she was marching. Andrea grew up in a “noisy, mercurial, dramatic matriarchy” of a family, with a single mom who worked full-time while raising her kids. She feels strongly that her liberal-arts education — an education her mother and female relatives never got to have — was both their gift to her and a force that threatened to distance her from them. The women in her family didn’t grow up thinking about identity politics, eventually preferring to define themselves as “taxpayers and as people who made it.” Many of them voted for Trump, and see Andrea as “this somewhat radical naïve bleeding heart.” But as Andrea told me, “Everything I am has been a straight line from these women.”

Andrea loves the urgency of marches, their powerful alchemy of compassion and righteous anger. But she found the Women’s March more mixed, clearly full of first-time marchers — many nervous, hesitant to chant anything besides the most familiar anthems — and driven by diffuse objectives. It also felt disorganized. “I don’t think you necessarily felt the history of the moment,” she said, “while standing there silently in ten-minute stretches, waiting for the march to move along.” But she also felt the joy of spending the night before Inauguration Day with friends, “making posters and thinking of slogans while eating takeout and watching Star Wars.” At the march, she felt she was witnessing the “birth of something massive and collective that didn’t quite know how to articulate itself yet.”

We know that we gather this afternoon on indigenous land,” Angela Davis told us as we stood in the shadow of the Smithsonian. “This is a country anchored in slavery and colonialism.”

A middle-aged black woman standing beside me said, “Yes, yes, yes!” She said, “This is awesome. I haven’t seen this lady since 1986.”

Angela Davis said, “The next one thousand four hundred and fifty-nine days of the Trump Administration will be one thousand four hundred and fifty-nine days of resistance.”

The seven days that followed the march were a nightmare of presidential orders. Trump reinstated the oil pipeline that would run near sacred Sioux land in North Dakota. He mandated a gag on federal funding to global health providers that offered abortion counseling, and issued orders to start building a wall along the Mexican border. He announced his plans to publish a weekly list of crimes committed by undocumented migrants. On January 27, just a week after the march, he issued a ban on refugees coming into the country, and on all citizens of seven predominantly Muslim nations, which meant that passengers in the air when he signed the order were detained in airports upon arrival. These executive orders are offensive to reproduce in summary. Every part of me fights the possibility of their normalcy, fights the neutral tone of reportorial prose, fears what will happen between the writing of these words and their publication.

The morning after the Muslim ban (a term the president and his advisers have vehemently resisted), protesters started gathering at JFK’s Terminal 4, where two Iraqi men were being detained. One had worked as a translator for the U.S. Army for more than a decade. Word went out over social media, and hundreds, then thousands, of people began flooding JFK and other airports throughout the country: LAX, Dulles, Houston, Sea-Tac.

My husband and I took the A train to JFK from Manhattan after we bought posters and markers from a downtown drugstore and scribbled phrases from Emma Lazarus’s Statue of Liberty poem: give me your tired, your poor.

The protest began before we got to the protest, at the Howard Beach AirTrain station. As we were waiting to buy our tickets, we saw a line of cops forming on the other side of the turnstiles. “Only ticketed air travelers and airport employees allowed to board!” they said. There were so many of them, so quickly.

My husband asked one of them, “Is there a regulation allowing you to do this?”

He asked my husband, “Are you a ticketed traveler?”

“I don’t know,” my husband said. “Am I?”

I could feel the molecules of the room vibrating and rearranging. The cops were multiplying. The protesters — mostly strangers, all of them intent on boarding the same train — were gathering into a sudden, spontaneous collective.

“What you are doing is wrong!” a woman said. And then the chants began: “If we don’t get it? Shut it down!” I’d been in this station countless times — running late for a flight, checking email on my phone — and it was strange to see it as the site of such fervent desire, such heated conflict. The turnstiles were the obstacles keeping us from the protest, which meant they had become the protest.

I wish I could say I stormed the barricades, or cajoled the conscience of a Metro Transit Authority employee. The truth is, I just started thinking of another way to get to Terminal 4. We ended up catching an unmarked cab from a pizza place across the street, sharing a ride with an immigration lawyer who was trying to link up with a group of immigration lawyers already there. “They say they’re in the diner,” she said. “Where’s the diner?” We saw more cops approaching the AirTrain station, putting on their N.Y.P.D. vests, heading upstairs to the showdown at the turnstiles. Were we making our way to the protest, or were we fleeing it? How could we tell?

When we finally got to Terminal 4, the crowds went all the way back to the parking lots. It was cold. Someone had projected the word resist on the concrete wall of the parking structure, and then the words let them in. People had filled the structure, were standing at the edges — in rows, dangling their banners — looking out.

This was protest. Not just the perilous electricity of the AirTrain station, bodies blocking other bodies by force, voices crying out in response; and not just the stark beauty of those luminous words across concrete; but also the tedium of an hour-long subway ride, the uncertainty of what to do or where to go when the protest did not go as planned. It was the immigration lawyer wondering, “Where’s the diner?”

“Mic check!” someone called, and then proceeded to warn anyone undocumented that they should leave, in brief parcels of language that turned into communal chants: “The police may be coming! If you think you are in danger! Protect yourself!” Then another call-and-response began, its force only deepened by its familiarity. “Show me what democracy looks like!” And the response: “This is what democracy looks like!”

That answer gave me chills, in total earnest, every time.

Like my mother, the old mythic marches weren’t myth; they were life. They were full of flawed people and bored bodies. But it matters that they happened. What would our collective story look like if they hadn’t? What would our collective story look like if it didn’t include a massive gathering after Trump’s inauguration, if it held instead a vacancy — thousands of people in despairing, isolated, private disbelief? What if the ban on refugees came down and no one marched at all?

A few days after the election, Greenpeace hijacked a construction crane near the White House and hung a rainbow banner that said resist. The banner thrilled me, but I also knew that thrilling work wasn’t the only kind that mattered. When Alice Walker said that the “real revolution is always concerned with the least glamorous stuff,” she wasn’t talking about flying giant flags from giant cranes. She wasn’t even talking about the logistics of 500,000 people marching, bringing enough trail mix and backup onesies. She was talking about ongoingness: showing up past the first flush of indignation and sticking with it. She was talking about the daily tedium of tutoring, voter registration, helping people fill out food-stamp applications. She said that one of the great achievements of her life was taking a bag of oranges to Langston Hughes when he had the flu.

“Militancy no longer means guns at high noon, if it ever did,” Audre Lorde wrote in the 1980s. “It means doing the unromantic and tedious work.” This will never be the stuff of cinematic grandeur. It’s never satisfying, in part because it’s not enough. It should never feel like enough. But invoking insufficiency as an alibi is just as dangerous as self-righteous satisfaction or comfortable despair — the very things Lorde warned us against.

A week after that chilly day in D.C., I sat with my friends Greg and Ginger in their Bed-Stuy kitchen, along with their daughters — Sara, twelve, and Fita, nine, who had marched with them — and their pet rabbit, Oliver, who had not. Ginger had never marched before. When I asked her about her activist history, her first instinct was to say she had none. Zero. But then she started recalling things that might have counted as activism all along: tutoring students in her class who were falling behind, back when she was a student herself, or working with kids in her local community garden. Ginger called this “lowercase a activism.” Alice Walker would have called it revolutionary work.

Ginger said that for her, the march itself hadn’t been about sacrifice or service, it had been about sustenance. “It’s going to be a long four years,” she said. Her family was from El Salvador, and she felt the potential breakdown of civil liberties as a real peril.

As for Greg, his earliest memories of collective action involved marching on the picket lines outside Newark International Airport when his dad was part of an air-traffic-controller strike. Greg was twelve. He and his father marched along the highway, and Greg remembered the chants, the union-hall meetings, the thrill of fighting Ronald Reagan as their personal enemy. Years later, he went to the Million Man March with his father and grandfather, and it made him feel connected to the black community in a more tangible way than he ever had before. This was part of what communal action could do: it could introduce you to collective identity in a way that didn’t feel forced or conceptual, that felt bodily, emotional, palpable.

Greg described a moment during the Women’s March when he started chanting because he heard Sara chanting beside him. This captured something true about chanting, and about inheritance: Both work like contagion. Both work in multiple directions. You never knew who might start chanting simply because your voice gives them prompt or permission. Ginger wasn’t a chanter — she was firm on that point — but she described one part of the Women’s March when she found herself chanting. It had been outside the Trump Hotel, the historic post office that Trump had converted and bragged about — ceaselessly, it seemed, in lieu of policy arguments — during the presidential debates.

As they marched past the hotel, Ginger told me, police cars drove through the crowds with their sirens blaring. “If they wanted to make us disperse,” she said, “they had just the opposite effect.” The sirens got her riled up, made her want to resist, to keep moving, to raise her voice. This was activism as generative friction, activism as diversion from plan, off-roading away from script: a protest at the turnstiles, AirTrain as flash point, sirens as tuning fork. This was guilt — or awkwardness, or showing up for uncertainty — as the beginning of knowledge.

My mom texted me photos from her march at LAX while I texted her photos from my march at JFK. She shared the news of her resistance, as she had always shared the news of her resistance, which wasn’t the ticker tape of myth but the stumbling notation of the actual. She recounted the pain of McGovern’s loss, the weeping voices on the other end of telephone calls, the protests she felt proud of, and the one she apologized for — decades later — to a veteran who hadn’t been there. She told me about the olive pickers, their hands covered in socks, and how good it had felt to stand with them by a blazing fire, when they got inside, after they finally said: Enough.

That Saturday, before the march-too-crowded-to-become-a-march became a march, when the multitudes were already tired of standing — hungry, shoulder to shoulder, antsy — the singer Janelle Monáe took the stage. She said her mother had been a janitor, her grandmother a sharecropper. “We birthed this nation,” she said. “It was a woman gave you Martin Luther King. It was a woman gave you Malcolm X.”

She introduced five mothers who had lost their sons to police violence. Each woman said the name of her son, and we called back, “Say his name.”

We heard “Jordan Davis,” and we said, “Say his name.”

We heard “Eric Garner,” and we said, “Say his name.”

We heard “Trayvon Martin,” and we said, “Say his name.”

We heard “Mohamed Bah,” and we said, “Say his name.”

We heard “Dontre Hamilton,” and we said, “Say his name.”

When you are talking about half a million people, saying something is more like a roar. You feel it in your body, in your bones. It vibrates the air. This wasn’t intersectionality as the heading on a college syllabus, it was the sound of primal, indisputable truth.

Each time Monáe passed the microphone to one of these mothers, she said: “This isn’t about me.” We heard the name of Sandra Bland. We heard the names of Mya Hall and Deonna Mason, two trans women of color killed by the police. Many of the mothers’ voices cracked as they said the names of their sons. To hear and feel the crowd around me saying “Say his name” and to feel my own voice as one small fraction of that crowd: it filled my whole body. It made me feel large and small at once.

This was one of the most important things a crowd of half a million people could do: stand in the capital of our country and listen to these mothers say the names of their sons. It wasn’t about me. I mattered only insofar as the we would be impossible without 500,000 individual voices. The we: pink-hatted and extending beyond our range of vision. Our mouths were parched and our voices hoarse. We were fidgeting. We were loud.

What mattered? The surge and force of us: half a million strong, nameless, calling for their names.