Leaving Home

From a conversation with a twenty-five-year-old Baghdadi refugee named Fatima, which took place in the storage room on the rooftop of a building in Amman, Jordan, where she was residing. Fatima moved to Jordan with her family in 2012, when her father began receiving threats. In 2014, she registered as a refugee with UNHCR, which referred her for resettlement to the United States earlier this year. Her interview with US Citizenship and Immigration Services was scheduled for February but was canceled following President Donald Trump’s first executive order barring entry to the United States for citizens of seven predominately Muslim nations, including Iraq, and halting admissions for all refugees. In July, after months of delays, USCIS began rescheduling interviews in Amman. Fatima is stuck in the backlog.

Since I was young, I’ve never felt safe with boys. I never had any relations with them, and when I got older, when I was a teenager, my friends would say to me, “I’ve got a boyfriend. Why don’t you have one?” I thought there was something wrong with me. My family and society all say it’s wrong, that how I feel is a sin, a crime. I tried to change my thinking, but my thinking wouldn’t change—this is something inside me. When I was nineteen or twenty I became sure that I couldn’t think about boys. I wished I could have a close friend who understood me, and I could tell her how I feel.

Then I saw my neighbor Mouna.

I knew that if I had a relationship or became really close to a girl, my family would lock me up, at the very least. They’d put me somewhere I couldn’t leave and tell me I had to get married.

My brother and I needed to finish our studies, so we were living in Jordan, but my parents went back to Iraq because my married sisters were there. When my brother went to visit Iraq, I’d stay with Mouna and her mom and dad. I felt like they were my family here. I didn’t have friends. They were everything—and Mouna was my everything.

One day Mouna came to visit me. We were playing with some puppies, and I was complaining about her resettling to America to join her brother, who was living in Kentucky. She was hugging me, and my brother opened the door and saw. He closed the door and got really upset. I went straight to my brother and told him, “Don’t get upset. We girls are different from boys. I was just telling her about my problems, you know, I’m not feeling well.” He just said, “Don’t talk to me, don’t talk to me.”

He’s my younger brother, but you must know how Arab society is—it favors boys. He got mad, and he was sure something strange was going on. So he called Mama in Iraq. My mom told him, “Don’t let her go to Mouna’s house.” My family tried to bring me back to Iraq. They told me to just live normally, get married like my sisters and live normally. But how can I live if my family doesn’t accept me? They feel like it’s a shame for me to live. They think that they should force me to get married. I didn’t want to. They had always forced everything on me: Cover your hair. Don’t be alone. Take your brother with you. I said okay to everything because if I said no, the problem would get bigger.

My dad came to Jordan, took my phone, and said, “Tomorrow, I’m having visitors.” The next day, three guys came to our house. My father asked me to serve the coffee. Usually, my brother does that, not me, so I felt something really serious was happening. But I thought, I will try to understand my father. One of the guys introduced his friend, and said, “It’s a pleasure that he would ask your father about having an engagement with you.” I think he was forty, forty-three, something like that, and he has a family—he has children, he’s married. His friend told me that he and his wife were not understanding each other or something. I don’t know, I didn’t care. I told him that I’m not going to marry someone already married with a family and double my age. My father was in shock. In front of his friends, I said to him, “With all my respect for you, respect my opinion like how I respect you. I don’t want it.”

So I left. My dad came after me and told me to go to the bathroom. I heard him say, “I’ll come with her tomorrow to visit you.” When they left, he came into the bathroom. He was super nervous and he said, “You don’t know how to respect people, and you don’t know how to respect your father.” I told him, “Dad, please, understand me. I promise you I’m going to do that but not now and not this guy.” So he hit me. And then he put me in the bathroom for the next day. I was stuck in the bathroom, my legs and my hands tied up with cables.

The next day, he told me, “Yalla, it’s time to go to these people.” He tried to get me out, but I was screaming, and I knew what would happen: he might give me to them. I tried to make noise, and he tried to take me but couldn’t, so he put me in the bathroom again. Suddenly, I felt something on my back, like a fire on my back. It was a barbecue stick. I smelled a really bad smell, and I couldn’t feel whether I was conscious or unconscious. And I told him, “Just tell me what you want. You might convince me if you talk to me, but not this way.” He told me, “I’m going to get you back to Iraq with me. Because you are so stubborn and you don’t listen to me. And I just feel shame about the way you are.”

I had long hair, and he cut my hair in front of the mirror. He didn’t cut it one time. He cut it in different ways, yani. Every hour, he’d come and take some of my hair, and make me look in the mirror, to make me ugly. He shaved my hair in different ways. So I saw myself in different shapes, and I hated myself. And then he just shaved it all.

He saw that I have a tattoo on my shoulder. In Chinese it says mouna is my soul mate. He said, “I’m going to burn your tattoo.” I thought, This time I’m going to die. I knew what he was thinking about the tattoo. I think he was in the kitchen, and I said to myself, let’s run to the door and just run away. I got out of the bathroom and ran to the door. I saw the keys there—my brother had left them—and I took the keys, opened the door, and ran. He was running after me. I just ran.

It’s been one year and three months since the incident with my father. I had my prescreening interview with the IOM on January 3. They called me a week later and told me about the US government interview, on February 28. I was so excited after this long wait and really tough process. But when I heard the news, the ban and the decision about refugees . . . I don’t want to think about it.

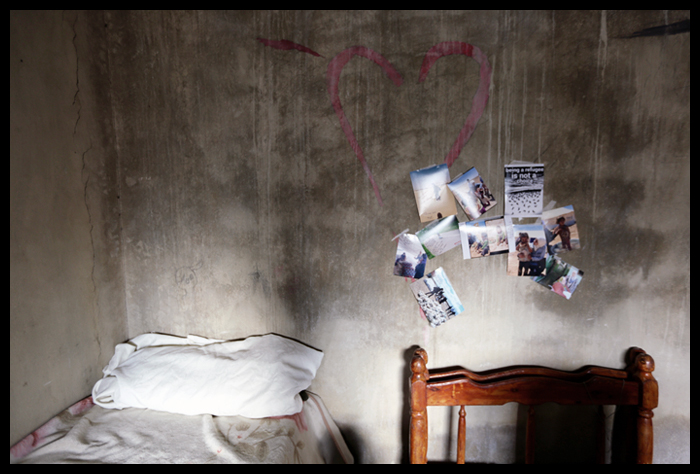

I stay here, I don’t move, I don’t go out, I don’t walk around. When there’s heavy rain and it’s windy, I can’t sleep at night. It’s cold, and I’ve been sick for days. The wood of the bed is really old, and bedbugs attack me all over my body and my face. And then I just want to not sleep at night. I don’t want to see the light. I don’t want to feel like there is movement of people around me. People go to work and people go to school, people go to university. I just wake up at night, and it’s quiet.

It’s been years, months, and then you know, whenever they give you hope, tell you that you have an interview, you have to wait for I don’t know how long. They give me hope, and then I feel hopeless again.