Indistinguishable from Magic

Dynamicland seeks to free us from our devices—through technology

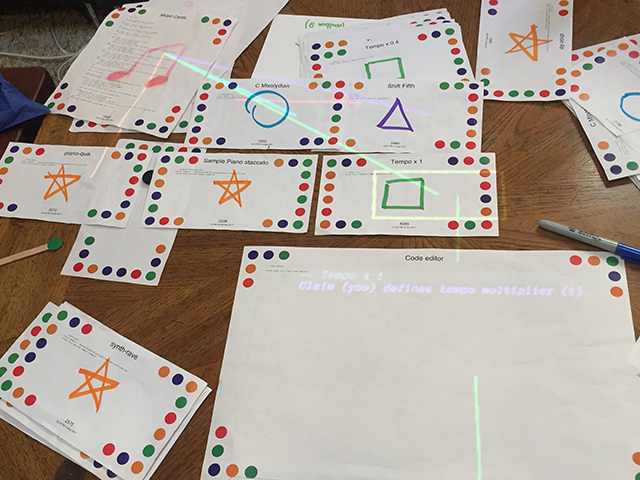

Rain was falling inside Dynamicland, but no one could identify its source. Bright, pixelated raindrops dotted a table covered with paper as the space filled with the soothing sound of a gentle rain shower. Dozens of projectors—large and minuscule—hung from the ceiling, their lenses aimed down at all manner of surfaces covered in white sheets of paper and immersed in flickering lights. Every piece of paper in Dynamicland is bordered by colorful circular stickers arranged in a careful pattern, which act as a kind of barcode that renders the paper recognizable as a piece of code. In Dynamicland, coding doesn’t mean tapping away in front of a computer—it means physically creating code on the page. Somewhere on its expansive floor, someone had evidently switched on the code for “make it rain.” A crowd of onlookers didn’t seem to mind.

A nonprofit research group with the feel of an artspace, Dynamicland was first conceived by Alan Kay, an influential computer scientist who is known as the “father of mobile computing,” and a designer named Bret Victor, who once held the title of “Human Interface Inventor” at Apple, where he helped create products like the Apple Watch. Together, Kay and Victor began working on their new medium in a research lab modeled on Xerox PARC, where things like Ethernet, laser printers, graphical user interfaces (and with them, the mouse) were developed. In late April, I went to experience the group’s nascent technology, which Victor sees as an antidote to the “inhumane” products he once helped create. Through Dynamicland, he hopes to destroy them, or at least render them redundant by inventing a new medium that does not require users to be chained to an illuminated rectangular screen. The space, which resembles an elementary school more than a lab or an office, was teeming with dozens of visitors gawking at the technology surrounding them, many of them wielding their smartphones like defensive shields, snapping photos of the simulations hovering over every surface.

Dynamicland belongs to a cohort of new Bay Area projects dedicated to freeing us from the tyranny of our devices. But where others have proposed simpler tactics, like disabling notifications, abandoning infinite scroll, and taking “breathers” from one’s screen, the team behind Dynamicland has taken a more radical approach, encouraging visitors to leave their mobile screens in their pockets and marvel, instead, at life-size programmable interfaces built into the lab’s walls and floors and furniture.

A team member handed me a brochure at the entrance: “The entire building is the computer,” it read. “We are inventing a new computational medium where people work together with real objects in physical space, not alone with virtual objects on a screen.” I looked around, waiting for this computer to reveal itself. Instead, what I saw would be more aptly described as a playroom for adults where every surface is a screen; men sat cross-legged on a carpeted floor before a projection of an interactive graph that was beamed down from an array of cameras and motion detectors fixed to the ceiling. Using popsicle sticks and rectangles of white paper lined with multicolored dots, they compared the life expectancy and GDP per capita of the United States, Japan, and China in 1987. The program mimicked the famously entertaining presentations of the late Swedish statistician Hans Rosling, who used data to teach people “how not to be ignorant about the world,” and became a fixture on the TED Talk circuit for his optimistic sermons about rising global prosperity. In a corner, a group lingered in front of a paper display labeled “exquisite corpse”; they knew they were supposed to do something to make the illuminated 2-D corpse come alive, but they couldn’t be sure what.

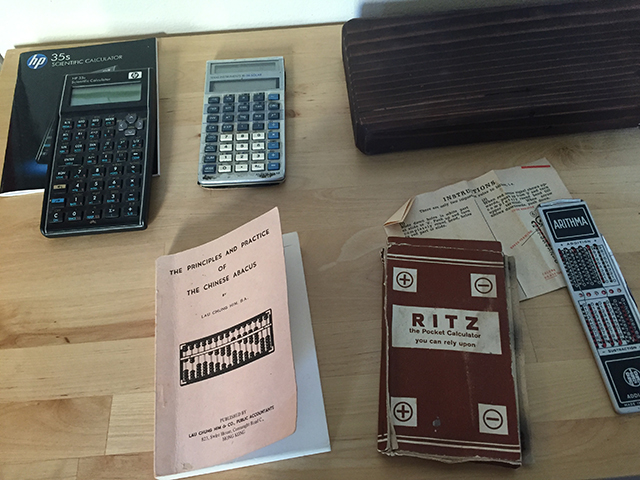

I wandered over to a small library, where there were couches, books—Einstein’s biography, The Last Whole Earth Catalog, and an encyclopedia of imaginary flora and fauna from a nonexistent world—and relics of computational mediums past (including a Ritz pocket calculator, a slide rule, a West German Addiator, and a weathered copy of The Principles and Practice of the Chinese Abacus). Above, a timeline traced technology’s evolution from cave paintings through written language, the public library, the printing press, disposable paper, personal computing; and then, finally, triumphantly, in 2050 ad, Dynamicland is fully realized and the dynamic medium is born. Standing before this display, in 2018, I had the feeling of both being ahead of time, and behind.

In 96 ad, the Roman Emperor Domitian was murdered in the defenseless position of holding a scroll with two hands. A few decades later, the codex, a predecessor to the modern book made from parchment and string, came into use, allowing readers to read with just one hand and to use the other for self-defense, if need be. At Dynamicland, Victor envisions a similarly emancipatory project, a technological advance that frees us from our laptops and cell phones. “We’ve invented media that severely constrain our range of intellectual experience,” he remarked in one talk. The answer to this problem, evidently, is to free us from our screens by turning everything into a screen, into a computerized, programmable, interactive interface. At one point, the sound of birds chirping filled the space, their songs interrupted by the enthusiastic cries of young programmers milling about before an interactive map of the Bay Area. “This is so cool!” one young man exclaimed.

Dynamicland might seem to be something like a life-size version of Microsoft Paint, or an unnecessarily aggressive enhancement of smart-home technology; in reality, it is something like both of those put together, a world where everything is interactive, where the divisions between the material and the virtual are obliterated, where simulations blanket our physical environment. The dissolution of these boundaries can be useful for things like playing games and presenting information, but it might also seem rather disorienting, and even dangerous, for those of us acquainted with the more inhospitable corners of the online world. For now, Dynamicland is dressed up as a whimsical place that frees its inhabitants from the tyranny of having to periodically glance at their devices, but it is easy to see how this new freedom can quickly start to feel entrapping. Dynamicland was certainly cool, but it was also frightening—if its technology can transform the entire world into a computer, what happens if you want to get out?

A few weeks after the community showcase, I returned to Dynamicland for an official tour led by Isaac Cohen, an artist and volunteer, and Virginia McArthur, the research group’s executive producer, who previously helped bring The Sims to life. On one table, an animated jellyfish—one of Cohen’s many dynamic creations—hovered over a piece of paper labeled “Jelly Rainbow.” He had written the code to connect every program on his workspace: each paper “page” became the end of a wiggling, neon tentacle. In a corner, a live feed of BART arrivals and departures illuminated the painted plaster wall.

By 2050, they hope, Dynamicland will have moved far beyond its Oakland headquarters, spreading into new cities and states not as a curiosity but as a piece of infrastructure, rendering all the surfaces—sidewalks, roads, streetlamps—into dynamic, programmable mediums. Around us, the walls and floors and tables glimmered with simulated shapes and sounds. Staring at an activated surface in Dynamicland is not wholly unlike staring at a screen, but it is far more pleasant: the colors are softer and slightly less alluring, which makes it that much easier, that much more natural, to look away.

“So much of what Silicon Valley believes is that technology can never be bad. But look at the history of what that is,” said Cohen. “I think everyone around here understands that we could really fuck this up, and that’s scary.”

Soon we were shaking hands and saying goodbye. Once I made it back onto the street, I fought the urge to pull my phone out of my back pocket, but I couldn’t find my way onto the freeway without it. Once I found my car, I sat down and opened Google Maps on my iPhone, and reveled, a little bit, in the thoughtless pleasure of listening to the navigator’s soothing staccato voice guiding me home.