Light in the Donbass Window

Among the “anti-imperialist” foreign volunteers in East Ukraine

Birtherism and 9/11 Truth, it turned out, were merely the prelude to the apotheosis of American paranoia. Global conspiratorial thinking now touches all our lives. On the right, schizo-fantasies such as Pizzagate, false-flag operations and crisis actors, George Soros as puppet master, and Holocaust-denialism have achieved maximum penetration. On the other end, liberals driven insane by Donald Trump have embraced the Serial-like amateur-investigator thrills provided by the daily drip-hope of Russian collusion—a reliable endorphin shot for an otherwise powerless and alienated opposition party, trapped in the spectacle of palace intrigue. Turn on cable news and you can see all manner of wild speculations presented as fact—fifty minutes of centrist think-tank experts and Deep State stans riffing on Melania’s “disappearance,” the secret messages that could be contained within Putin’s World Cup soccer ball—the whole effort laden with a desperate undercurrent of, We’re one step from impeachment. As these theories grow more complex, the Overton window shifts and the public atomizes even further, scrambling traditional left and right political affiliations.

While much of this loss of cohesion happens online—mostly among those who can be described as extremely online—there is a place in the real world that is a glowing beacon for a new breed of conspiracy partisan: East Ukraine. The “frozen” but still ongoing conflict in Ukraine has been a harbinger of polarization and a proving ground for the Kremlin’s information war. Most Americans would struggle to find Ukraine on the map, and getting untainted, unbiased information about the conflict is nearly impossible. Four years ago, in the wake of the Maidan revolution and Putin’s annexation of Crimea, protests in East Ukraine snowballed into an armed rebellion. The strategically vital coal-mining region on Ukraine’s border with Russia—known as the Donbass—had long been derided as an embarrassing, retrograde backwater, keeping the rest of the country from its true European destiny. Some of the uprising’s participants were local people who were tired of oligarchy and neoliberalism, and nostalgic for the Soviet Union; others were communists; others still were hardened anti-Semites raving about “Jewmaidan.” But the main rebel commanders shared a suspicious common profile: veterans of Chechnya, Afghanistan, and other breakaway wars, and “retired” Russian FSB colonels. Even weirder, some of the key figures were historical reenactors, with a special interest in cosplaying as the White Guard in the 1919 Russian Civil War. Kiev considered the East Ukraine rebellion to be tantamount to a second Russian invasion, and the two sides plunged into a grinding civil war that has left more than ten thousand dead and the country irreparably split, with no end in sight.

In 2014, the region voted to secede from Kiev-controlled Ukraine, reinventing itself as two nominally independent statelets—the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR). Wielding Novorossiyan flags, groups of foreign communists, hard-line Russian nationalists called National Bolsheviks (Nazbols, as they are informally known), and other unaffiliated anti-globalists poured in to volunteer as soldiers, propagandists, and aid workers. They viewed Crimea and breakaway East Ukraine as a golden opportunity to establish a buffer zone against the hated NATO. Since then, the region has been increasingly corralled by Russia. Most of the homegrown, independent local leaders have been murdered and quietly replaced by Moscow-compliant functionaries. Three months ago, when the longtime leader of the DPR, Alexander Zakharchenko, was killed by a bomb in a Donetsk separatist café, all sides had their familiar talking points ready: Russia, as usual, blamed the mysterious Ukrainian saboteurs; Ukraine said he was offed by his Russian minders; and others said it was a mafia-style rebel-on-rebel hit over money and resources. Still, for all the Russian meddling and involvement, there is no smoking gun proving that the Kremlin “activated” East Ukraine. Regardless, the war has mutated into a dangerous proxy conflict between NATO and Russia, each side keeping their people well supplied with arms, troops, and military specialists.

So when the Luhansk People’s Republic announced they were hosting a week-long solidarity junket for foreign supporters to “break the NATO blockade” and show “strength in unity,” I was intrigued. Various hammer-and-sickle communist parties from Russia and former Soviet bloc countries—as well as the “Community for Qaddafi and His People”—were listed as participating organizations on the slick website. I looked through the conference photos from the previous year: there was a South Asian internationalist fighter holding a Che Guevara flag, a hirsute Eastern Orthodox priest posing with camo-clad schoolchildren in front of a hammer and sickle, a Soviet-era Grad rocket launcher being paraded through the streets, and a framed portrait of Stalin.

Late one night, I wrote to the organizers for press accreditation and got an email back that instructed me to show up in front of Rostov-on-Don airport in Russia, and ended with the phrase “Red salute.”

I sat in front of my computer screen, hesitant to book a plane ticket. I had followed Ukrainian events fairly closely since Maidan and Putin’s seizure of Crimea. I was disgusted by the Ukrainian left’s Faustian bargain with ultranationalists that had enabled the rise of Swastika-tattooed Ukrainian Nazis, and felt vaguely sympathetic toward the scrappy East Ukrainian rebels—not Oliver Stone–sympathetic, but I understood that they were embattled and weak, trying to carve out their own small independent territory, with Russia trying to safeguard its geopolitical interests. But who were the good guys? The Russian ultranationalists seemed to be just as bad as the Ukrainian ultranationalists. The reality of the conflict was buried under layers of disinformation, obfuscation, escalation, and polarized academic debates dating from World War II: the Holodomor (the disastrous famine and mass relocation of ethnic Ukrainians), the anti-Semitism of the Bandera regime, the collaboration of Poland, Romania, West Ukraine. In the years leading up to World War II, countries in the pale of settlement found themselves wedged between two dictators, increasingly forced to choose between German imperialism and Soviet “anti-imperialism,” and these fractures echo and reverberate within this present conflict, which carries all the weight of that unresolved history. Although the USSR has collapsed and the specter of “world communism” has been exorcised, the Cold War dynamic still persists, with all the old players appearing under new names: “Communist agents” have become “Russian trolls,” while “imperialist” European and American paranoia about Russian disinformation is gaining ground.

May Day demonstration in Luhansk.

I flew to Moscow and caught a cheap overnight bus to Rostov-on-Don, plowing through the starry expanse of provincial Russia. An ultra-low-budget Russian sex-and-crime show blared on the TV. All the passengers stayed up and watched, transfixed—the bad guy was American. I arrived in Rostov as the city was gearing up for Victory Day, Russia’s biggest holiday, a celebration of the Red Army’s victory over fascism. Red flags flapped in the wind, tank memorials were adorned with glitzy hammer and sickles, and every billboard and bus was covered in neo-Soviet regalia. Most of the city’s residents walked around wearing patriotic black-and-orange ribbons. In front of the city’s small airport, a white-haired German woman in heavy blue mascara held a handwritten placard that read international anti-fascist conference. She said her name was Marin. She directed me to the parking lot, where, near a rusty van covered in anime girl decals, a gaggle of young men in sunglasses cavorted as if they were about to go on spring break.

“Welcome, comrade. We’ll be leaving in fifteen minutes,” said Tobias, the squirrely-looking German organizer of the convoy. He was wearing a bright red Putin T-shirt that said the world’s most polite man in Russian—a common reference to the polite masked Russian paramilitaries who materialized on the streets of Crimea during the annexation crisis. Tobias worked as a computer programmer in Munich and ran the group called Anti-Imperialistiche Aktion in his free time. He said it formed in 2011 as a response to the German left supporting the overthrow of Qaddafi’s “socialist” regime in Libya; since then, it has staged rallies calling for Russia to intervene militarily in Syria and East Ukraine. “There’s no real left movement in Germany today. It doesn’t exist,” Tobias said. “The majority of German people don’t like the USA. The majority is very much in favor of Putin.”

I told Tobias that Angela Merkel’s Germany looked pretty good from America—a robust welfare state, a progressive refugee policy, Die Linke (Germany’s democratic socialist political party). “Die Linke . . . ,” Tobias scoffed. “Imperialists.”

“Germany is a dystopia,” a baby-faced German guy chimed in.

“When I saw that video of Hillary Clinton laughing when Qaddafi was killed . . . I’ll never forget that. It was just so horrible,” Marin interjected, in a non sequitur.

Though they wouldn’t necessarily self-describe as such, these people were clearly tankies. The term tankie first emerged after the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 as a way to describe a certain type of unreconstructed Marxist who rationalized away the interventions in Eastern Europe and believed socialism could be spread by the barrel of a gun. It has recently made a comeback within Left Twitter debates to label a new breed of meme-happy Stalinist who accuses everyone on the left of being imperialist, bourgeois, or in the pay of the CIA. Tankies have little interest in Western notions such as human rights or any incarnation of radicalism that conceals a kernel of liberalism. They tend to be nostalgic for the sunken Atlantis of Cold War communism, when the Soviet bloc seemed to offer a heavy-handed “anti-imperialist” alternative to neoliberalism—a pre-1989 world many millennials are too young to remember. Like their inverted other, the mysterious alt-right neo-Nazi Pepes, the majority of tankies tend to be extremely online young men who you don’t often encounter in real life.

The Donbass is the spiritual homeland, the Olduvai Gorge of all tankiedom. An old propaganda poster depicts the Donbass as the beating heart of the Soviet Union, supplying coal through its ventricles. This proletarian heartland was the key to the USSR’s rapid industrialization and was venerated during Stalin’s grueling five-year plans. It was the birthplace of the Stakhanovite “shock worker” movement and was central to driving back the Nazis during World War II. Many of the Bolshevik nomenklatura who formed Stalin’s trusted inner circle came up through the East Ukrainian party farm leagues. In his memoir, Nikita Khrushchev noted, “We all came from the South—from the Donbass, from Dniepropetrovsk, and from Kharkov.”

Tobias unfailingly supported Bashar al-Assad, Chechnya’s Ramzan Kadyrov, Kim Jong-un, and Putin because they were anti-imperialist. He had only been to East Ukraine twice before but was hoping to get the country’s leadership on board with some kind of bargain-bin “anti-imperialist alliance” he was trying to set up. Though Tobias had no mandate to do so, he had already been in touch with representatives from the Syrian, Russian, and North Korean consulates in Germany, and had been invited to Damascus to meet Syrian regime officials, including Bashar al-Assad.

Suddenly, he no longer looked like a harmless German wing nut but more like a person probably in the crosshairs of several countries’ intelligence agencies. I asked him what was so anti-imperialist about supporting Russia, which today is just another oligarchic capitalist country. He said that Russia basically has the same foreign policy today that it did during Soviet times.

“Have you met the other American, Don, from Students and Youth for a New America?” Tobias asked as he introduced me to a guy who, aside from the oversize Lenin button on his shirt, looked like a college Republican. Don was an undergrad at Rutgers and spoke fluent Russian. I found myself wondering if Don was some kind of junior CIA asset. Students and Youth for a New America sounded made-up. I stepped away for a minute to Google it and was a little ashamed to find that the club was real.

We piled in the ratty old van and took off toward the Luhansk People’s Republic. Aside from Marin, the rest of the international anti-fascists were excitable young tankies—a Serb, a German, a Russian, and a Canadian. In the back of the van sat a hulking Ukrainian partisan from Kharkiv (as Kharkov is now known). He spoke little, except to say he had been tortured in Ukrainian mental institutions for his pro-Russian views and had fled to Moscow. His troubles seemed at least partly related to a controversial PhD dissertation he had written on the Holodomor.

The conversation during the drive focused exclusively on communism. Don held forth on his views of Trump’s America, explained the rise of the word “cuck,” and also said that Antifa and anarchists are a distraction from the real struggle. “We don’t call Trump a fascist. His travel ban wasn’t Islamophobic, it was imperialist,” he said. Leon Trotsky and Marshal Tito were dunked on. I was asked if I knew “the New York Maoists.” At a rest stop, some of the guys asked me, “What’s your position on Stalin?” I hesitated before saying that Stalin was a paradox, the Soviet Sphinx. I was beset with jeers and boos.

The area between the Russian border and Luhansk People’s Republic is tightly controlled—the Russian security services keep a close eye on everyone entering and leaving the republics. It’s alleged that the breakaway pro-Russian territories—Transnistria, South Ossetia, Abkhazia—are entirely stage-managed by Putin’s Tupac-loving political technologist, Vladislav Surkov. Hacked emails from Surkov’s office showing his involvement in the minutiae of DPR politics seem to reinforce these allegations. A new set of emails leaked from Surkov’s deputy to the Times earlier this year included an estimated budget for Russia’s information war; the cost of a month of Astroturfed pro-Russian rallies in Kharkiv is set at $19,200. (The Kremlin has disputed the authenticity of the leaks.) The role of “political technologist” has no direct corollary in the American context, but this hybrid position of senior adviser, creative director, and Mad Men–like purveyor of new political realities now has a strange and vital place in Russia’s creative class. Surkov was the original—he helped create Putin, back in 2000.

“All political positions in the ‘republics’ are controlled by Surkov. All members of parliament, all ministers in government,” Nikolai Mitrokhin, a scholar of Russian nationalism, told me. “Military decisions [in the republics] go through the Russian Defense Department and the Federal Security Service (FSB).”

Uniformed men searched the van with dogs and bomb-detecting mirrors. Tobias was asked to come inside for an interview with Russian FSB agents. With his Putin shirt, I thought it would just be a quick, friendly chat. But an hour passed, then two, then four.

Eventually, Tobias sauntered out of the station with a big grin on his face. He had been questioned beneath a framed portrait of Felix Dzerzhinsky, or “Iron Felix,” as the notoriously sensitive director of the Bolshevik secret police was known. Two agents went through Tobias’s phone and demanded to know who was really behind Anti-Imperialistiche Aktion. Tobias seemed unfazed, even charmed by the Soviet authenticity of the interrogation. As soon as he got into the van, he put on a pro-Soviet German song, an ode to Iron Felix, and the other tankies sang along. They knew every word.

On the Luhansk side of the border, a jolly bald man named Andrei from the Trade Union Association jumped into the van. Two police escorts appeared in front and behind us. “Welcome to socialist paradise, comrades! You are now our prisoners!” he laughed. With blue lights flashing as if we were visiting diplomats, the van flew down an empty, rutted road, over hills and past the otherworldly triangular mountains of coal slag rising in the distance.

Official first of May demonstration in the city of Luhansk.

The trade union’s hotel was hidden among foliage on a quiet street on the edge of Luhansk. In the springtime, the city has the eerily beautiful, post-apocalyptic look of Appalachia: rolling hills and the tragic pockmarked feeling of coal country. A string of Renault and Volkswagen car dealerships stood boarded up and looted alongside the main drag into town. Weepy trees and vines sprawled onto the roads studded with potholes. The area was heavily shelled in 2014—some of the hotel’s second-floor windows were still covered with plastic tarp. Running water was sporadic.

“Welcome, welcome to the free world,” Andrei said, passing out large bottles of vodka. “A free place is anyplace where there is no US embassy.” The hotel bar was filled with the rest of the solidarity caravan—thirty or so Italian, South American, and Russian internationalists and an Italian European Parliament member, most of them paunchy, aging punk rockers. As a result of a rash of drunken soldiers stabbing and murdering one another in bar fights, both republics were under a strict military curfew—anyone on the streets after ten would be arrested and detained by the notoriously brutal local secret police, the MGB, which works hand in glove with the FSB and Russian military intelligence.

In the lobby, I met a young Sikh foreign fighter named Rav. Before coming to Donbass, Rav had worked for a restaurant in New Zealand. A revolutionary communist, he had ventured to the Donbass alone, eager to fight for communism. “We have people here from all countries. There are many, many Russian fighters who are not communist . . . Duginists,” he said. “In Europe, a Duginist is basically considered like a fascist. They try to pass themselves off as anarchists, but we know who they are.” Alexander Dugin, Russia’s best-known Nazbol ideologue, whose ideas have penetrated Kremlin foreign-policy circles, told me that he was the “inspirer” of this Eurasian vanguard when I interviewed him in 2016. “There are many, many groups of the Russian patriotic movement there [in Donbass] fighting there as volunteers . . . It’s a kind of high school, because we are preparing a kind of intellectual elite for the patriotic field,” Dugin noted.

Rav said that a major ideological split had taken place, with the communists booting the Duginists from the international unit. “You know, if you don’t have a good feeling, it’s impossible to fight side by side as comrades,” he explained.

Another Italian communist fighter I met at the party told me he had joined the militias by just showing up in Rostov-on-Don. He said his contacts had instructed him to wait outside the airport wearing a black scarf. But no one showed up, so he spent the night on the bench at the Rostov train station, surrounded by Russian guys who were fighting and yelling. The next morning, he said he was picked up and blindfolded before he was taken into rebel territory. One of the main rebel commanders had been murdered in the days before he arrived. As an unknown outsider, he was considered innately suspicious and kept in the dark for a few days until he earned their trust.

Before turning in, I took one last peek into the bar’s wood-paneled great room. The tankies and the large Ukrainian were still raging, doing shots and singing old Soviet songs. For some reason, a war zone nuzzled up against Russia was the ultimate place for these young men to get fucked on vodka and wear fur-lined hammer-and-sickle hats.

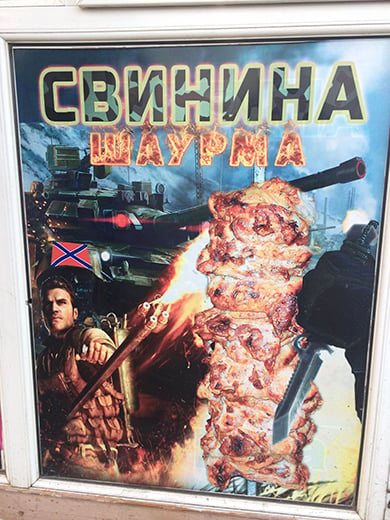

A poster parodying Hollywood movie titles like Crank: High Voltage that reads Pork: Shawarma.

In his tight green camo and black-framed glasses, Anton Gokhorov looked more like a model than a mercenary. It was my first time meeting a self-described Russian imperialist. He actually did some modeling on the side—scrolling through his phone, he showed me fashion shots of him posing with buxom, Kalashnikov-wielding rebels. He reminded me of an action figure, the Russian version of the soldier-scholar—good-looking, cold, arrogant (and in his early twenties.)

Gokhorov had left his political science program in Saratov, Russia, to fight in East Ukraine. On his shoulder was a patch with the Novorossiya flag. He was continuing his multidisciplinary studies at a university in Luhansk. I found him to be frighteningly intelligent, well spoken, and ambitious—it was like meeting a young Russian Bill Clinton. He said he had gone to Ukraine at least partially in service of a future political career. “I’ve never considered Ukraine as separate from Russia, Ukrainian people as different from Russian people. My life goal is Russia as an empire, Ukraine as part of Russia as well as Belorussia and all the other parts,” he told me. “I want my children to live in a large, strong, and independent state.”

He had worked for a time as a political scientist in Moscow and said he was on the board of a center for Eurasian studies. He knew Dugin personally and was friends with his daughter. His summer plan was to undertake a “systematic reading” of Dugin’s massive Russian-language oeuvre.

When I asked Gokhorov what he thought of Putin, he shrugged, saying, “I try not to think about him. I’m not a fan of any political leaders currently or in the past, aside from Stalin, a little bit.”

He spoke in terms of “civilizations,” “multipolarity,” and geopolitics. “Russia is a separate civilization, not European, not Asian—Eurasian. Eurasianism is the closest and best option to my goals and the goals of my nation in the future . . . I’m not against any of the countries who are geopolitically against Russia, because I completely understand that they have their own interests that are against Russia’s interests.”

Banda Bassotti playing in Krasnodon.

The International Anti-Fascist Conference was held in the city’s main Soviet-era theater, the Luhansk Regional Theatre of Russian Music and Drama. The outside of the building was covered in a fun-house façade depicting Alexander Nevsky, Russia’s national hero. The text below the illustration read, russian lands: whoever comes by the sword will die by the sword.

Igor Plotnitsky, the president of the LPR, received a standing ovation when he walked into the theater’s conference room. A big cigar stub of a man with frowning fish lips, he looked like Sal “Big Pussy” Bonpensiero from The Sopranos. Little is known about Plotnitsky’s past: he was a Russian soldier and for a time worked in the heavily criminalized gas trade. He came to prominence as a guerilla commander during the 2014 uprising, known for his ruthlessness. “Plotnitsky is a man who killed all people around him,” Mitrokhin, the scholar, told me. “It was very important to kill the independent commanders, because Plotnitsky, at the end of 2014, only controlled twenty-five percent of the LPR territory. He scored a very good relationship with the Russian government and presidential administration. He’s very smart and very dangerous.” Two years ago, Plotnitsky narrowly survived a car bomb assassination attempt. The next month, his parents suddenly and mysteriously died after eating “poisonous mushrooms.”

“Democracy is a good form of government. But the democracy of double standards is not suitable for us all,” Plotnitsky said in a deep baritone. “We want to prove to you that democracy is working here. We can speak openly on any topics. We have no prohibited topics.” Eleonora Forenza, the European Parliament deputy from Italy, gave a speech castigating the European Union for supporting the “Kiev Junta” and lauded the republics while wearing a T-shirt that read not in my name. “Complicity with the Kiev regime is complicity with fascism. My first task when I come back to the European Parliament will be to ask about recognition for your republics.” Plotnitsky smiled like a cat that had just eaten a bird. He was getting what he came for.

“Thank you for the very interesting speech,” he grinned. “I would like to say some words which might at first sound offensive—none of the European countries managed to withstand fascism. But we have beaten it twice. And we will beat it again.”

Speaker after speaker—Spanish communist skinheads, Italian unionists, and a Senegalese immigrant––stood up to tell Plotnitsky about the greatness of the republics and the evil of NATO and the Kiev fascists.

Don offered to open a foreign office in the United States, saying that he and his comrades there would do whatever they could to help the cause of the republics. (After this reporting, Don went on to work for RT.) Plotnitsky smiled and turned to the pro-Russian Europeans. “Loads of you have said you fight against NATO. In a few brief words, Why, why are you against NATO?” There was a long, sheepish silence. Giorgio, a middle-aged Italian militant, broke the silence: “It’s because we think . . . we think NATO does not have to exist!” The room roared with thunderous applause.

Plotnitsky seemed amused. “God forbid, if we have to fight, NATO won’t protect you. I’m sorry to say it, but it’s true.” By the end, the man, who has probably had his political and military opponents killed, was soft and beatific. “Humanity has a very big and very good dream: its called the age of kindness. Let us visit each other not with wars, but with good intentions, with gifts and presents. Let us try to establish the age of kindness not in our words but our deeds. And believe me, you will not find a more kind and hospital people than the Russians.”

When I met Nemo outside an orphanage in Luhansk, he was ready to leave East Ukraine but wasn’t sure how to get back home. His EU passport had expired. A handsome Italian communist in his late thirties, he had spent two years fighting in the hundreds of kilometers of trenches that divide East Ukraine from Kiev-controlled Ukraine. As a commander of the InterUnit, he led a ragtag band of European, Latin American, and Indian anti-imperialist foreign fighters who had ventured to the region, drawn in by the rhetoric of defending the “people’s republics” against Ukrainian fascism. He told me that he and his fellow internationalist guerillas were armed only with the vintage Soviet sniper rifles they had managed to loot from small-town museums and ancient artillery they had pried up from public parks and World War II monuments. The hammer and sickle, the Lenin statues, the Red Army tanks, the cries of No Pasarán! against the fascist invaders—it was almost like a historical reenactment with live ammunition.

But now East Ukraine’s Russia-controlled administration was closing down the international brigades, attempting to incorporate them into the regular command structure, leaving Nemo adrift. He was waiting for his Luhansk People’s Republic passport to come through. With that, he could cross the border back into Russia. From there, he planned to walk across northern Finland back to Europe, like Warren Beatty in the movie Reds. He was already thinking of lighting out for South America—the constitutional coup in Brazil presented some “interesting opportunities” for the twenty-first-century guerilla. The war in East Ukraine seemed to have left him a bit disillusioned. “I don’t want to be a puppet for the United States or for Russia. I came to fight for people.” Despite all the Russian “voices” and money running the war, the Russian equipment, the Russian Duginists and imperialists fighting alongside him, Nemo refused to acknowledge that he was basically fighting for Russia.

“There’s a big misunderstanding about this situation,” he told me. “The people from here made the republics because they’re nostalgic for the Soviet Union. But this absolutely does not mean that they are communists.” He disputed the widely held belief that Russia had covertly “activated” the Donbass uprising and is in charge of the republics. “It’s not true that this is a war for Russia. The truth is: Russia absolutely didn’t want the war in Donbass. The people here rose up without Russia. And for Russia, it was a big surprise. Russia said, ‘What are we going to do with these people?’ In the uprising, the people of Donbass made a people’s republic, something similar to the Soviet Union, not Russia. Russia is a state of neoliberalism and oligarchy, and the people here wanted something different from that.”

Old statue of author Maxim Gorky in Krasnodon, which is in the Luhansk Peoples’ Republic. Aside from Stalin, Gorky was the most heavily memorialized figure of the now-erased Soviet canon.

I took a bus to the Donetsk People’s Republic, four hours away. The rolling hills, meadows, and small, destroyed houses were strangely picturesque. The bus turned onto a dirt road in a field and stopped at the border, at a bombed-out village manned by a couple of guys with Kalashnikovs who waved us through with no trouble. Immediately over the border, all the villages and roads appeared much nicer, better maintained, less post-apocalyptic and weedy than Luhansk. I sat next to an elderly teacher who lived in the border between the two republics. “DPR is so much better than LPR,” she said. “Putin is just waiting to annex us. If Russia didn’t want us, why would they spend so much money on us? And they’ve spent a lot of money on us.”

Donetsk is a modern, clean city, with a nice river walk and leafy, meandering plazas. If it weren’t for the periodic dull booms, which almost sound like fireworks, you wouldn’t know the neighborhoods just outside the center are surrounded and are periodically shelled by Ukraine’s Anti-Terrorism Operation forces. The main administrative building in the center of town is covered with faded graffiti from the 2014 uprising, with the Orthodox cross and tags reading, russia, we can’t step back donbass is behind us, and god is with us.

I met Yuri Dergunov at a chic burger restaurant in the center of Donetsk. Wide rows of soldiers goose-stepped up and down the boulevard behind us, drilling for the upcoming Victory Day celebrations. A rumpled, left-wing sociology professor with glasses and a ponytail, he looked nervous and kept dabbing his forehead with a handkerchief. Dergunov was part of a small group of independent Ukrainian socialists critical of both the repressive ambiance of the republics—in which the ever-present threat of Ukrainian nazi hordes are used to keep the population in a keyed-up state of emergency—and the frightful ultra-nationalism metastasizing in Kiev-controlled Ukraine.

He told me, “I felt very much alien to both sides. Basically, people here were motivated by some image of the enemy of Ukrainian fascism that was only true in a very small way . . . There were certainly some fascists on the street during Maidan, but no way to call the new government fascist . . . It became a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. The war against the separatists made the explicitly fascist forces much stronger.”

He said Russia had been actively involved in shaping the ideology and policies of the republics, and continued, “I don’t think the regime here can provide any progressive alternative to capitalism. What I see here is that two sides started the war, mainly under nationalist banners—some people fight for Ukraine, some for Russia—but none of this has anything to do with the interests of labor.”

Dergunov saw little reason for hope or optimism. “We will become closer and closer with Russia in terms of economic and legal integration, but this will all happen without joining Russia. This territory will become a kind of ghetto, so to say, with very low-paid people . . . I think the area will become important to Russia as not only a source of immigrant labor but as a kind of industrial maquiladora district.”

Krasnodon, on the Russian border, was the site of much Soviet partisan resistance during World War II, while under fascist occupation.

The man known as Janus the Finn picked me up near the river walk in Donetsk in a black Range Rover. Janus—named after the ancient Roman god of doorways and passages—looked hungover. He was wearing sunglasses and chain-smoking; an empty half-pint of vodka was tucked in the passenger-side door. He ran the republics’ Breitbart-hysterical news agency, DONi News. He was also in charge of keeping tabs on all foreigners, particularly foreign journalists. Without Janus’s blessing, it was nearly impossible to work or even be in the republics. “Welcome to the free world,” he said, in his gravelly baritone. “Here, men are still men. And the women? They’re beautiful.”

We sat on a pizza restaurant’s patio. I couldn’t stop staring at his huge knuckles. He cracked them and massaged them as we talked. More than six feet tall and physically intimidating, Janus had spent fifteen years in the Finnish military. In Helsinki, he had run an Infowars-like alternative-media outlet that apparently garnered him so much notoriety that he fled the country. “For two years, I couldn’t go to a restaurant without a bodyguard. In Finland, we see how the globalists take over our politicians and turn them into fucking psychopaths.”

He came to the Donbass knowing three words in Russian: “yes,” “Putin,” and “cigarette.” “What I see is that this is an anti-globalist war. Some people here are communists, are here for ideological reasons, but what connects everyone here is that they are anti-globalists. It’s mostly a war against the Western power structure, but also the Muslim Brotherhood, Masonry, and the Illuminati.”

Within a year, he had started a state news agency with a staff of fifteen, run out of the DPR’s presidential administration offices. He was open about the coordination with the Russians. “They are working with us on every fucking level. There is the intergovernmental connection and integration based in Rostov that is very active. You see Russian envoys coming and going on a daily basis . . . It’s not hidden, but it’s somehow hidden. It works very much directly under Putin’s administration.”

He was breezily confident about the war effort, claiming that it wouldn’t be long until their tanks were in Kiev. “We are waiting for Kiev [the Ukrainian government and its NATO military specialists] to make their last mistake and try to attack. We will not attack. But if they do, they will be destroyed. We have four armored brigades ready to make a counterattack. There will be no third cease-fire agreement. We will destroy them from the moon.”

Pro-intervention poster in the Night Wolves motorcycle gang clubhouse depicting Kremlin leadership as an army squad. From left-to-right: Churkin, Lavrov, Surkov, Putin, Rogozin, Shoigu.

I was day-drinking in the basement of Havana Banana, a kitschy Cuban revolution-themed bar, with a Catalan social democrat named Miguel Puertas, the Sikh fighter Rav, and a gray-bearded man with a British accent. The bar is notorious as a kind of Mos Eisley cantina, where the scum from across the universe drains and where rebels of different ideological persuasions frequently fight one another in drunken arguments. Like nearly every other foreigner, Puertas washed up in Donetsk because his rabid anti-NATO views hadn’t gone over too well in Europe. A prolific and eccentric blogger and social-media personality, he had a job at a Lithuanian university but was given an ultimatum to stop posting. He kept posting and was dismissed, and he now refers to Lithuania as “Fascisthuania.” Puertas ranted against Femen, feminism, Pussy Riot, identity politics, and George Soros, while the gray-bearded guy nodded in agreement. “George Soros, mannnnn . . . He used to be a communist. He used his communist knowledge to make himself rich. He’s like Darth Vader. Pure evil.”

Sitting quietly at the end of the table was a pale young student from a local university. He said he lived in Kievsky, one of the city’s neighborhoods that had been obliterated by Ukrainian bombs. “A few months ago, my district was on fire. But now it’s quiet. And when it’s quiet, I get scared, because that means another escalation is coming soon.”

Across the table, Puertas was shouting again. “Donetsk is becoming a police state. The right wing, Putinists, and the right wing. You should avoid them. The MGB and the KGB. Janus Putkonen—this guy is a mafia guy. . . I think he’s the Kremlin . . . All the Finnish here are a group of far-right anti-globalists . . . The Spanish here are on the left. They don’t like the Spaniards here. They’re blocking all of our initiatives. I think behind it is Janus Putkonen.”

Residents of Krasnodon enjoying a solidarity concert from Banda Bassotti, visiting Italian supporters.

It was a mess. Full-blown Swastika-tatted Nazis on the Kiev side, nazbols and Duginists on the Donbass side, a few critical leftists stuck in the middle. I felt bad for Nemo and a few of the other good-hearted internationalist fighters who had come to build communism and ended up as de facto Russian pawns. In what could be the postscript for so many left-wing movements in the past 250 years, Nemo sighed and said, “We tried to build socialism and give power to the people. But things don’t go exactly the way we want.”

One thing Nemo said wormed its way into my mind—his view that the Russian position on Donbass was basically asking, “What are we going to do with these people?” The only country to officially recognize the republics has been South Ossetia, itself a breakaway republic. If Russia really wanted East Ukraine, why hadn’t they taken it yet?

Were the Russians as brilliant and sinister as we imagine them to be, or were they just winging it? They were bleeding international credibility and arms, and incurring sanctions, over this geopolitical black hole. Maybe Putin had activated East Ukraine with a light touch—enough to sew discord and confusion to his advantage. But maybe the situation had spiraled out of control and now Russia was just managing. Maybe the Kremlin regarded the messy republics as one might a troublesome situation with an embarrassing relative—you don’t want them left out in the cold, but you also don’t necessarily want them to move in with you. And as everyone knows, only you can criticize your family.

I found myself thinking about something Plotnitsky had said during the conference that seemed to encapsulate the entire hyperpolarized, hall-of-mirrors nature of the Ukraine conflict, ground zero for the now-globalized Western and Russian information war. “Joseph Goebbels said that if you repeat a lie a thousand times it becomes truth. It’s easy to identify and stand against a lie. But a half-truth is the most dangerous thing, because it contains a kernel of the real truth.”

Shortly after I left the region, Plotnitsky attempted to remove his interior minister and was met with a palace coup from a competing faction within his government. Both sides had armed men outside the government building, and the situation threatened to turn violent. Plotnisky was held captive in his office, left dangling by his handlers in Moscow, then ejected from Donbass. A cell phone video shared online shows him walleyed and shambling through Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport with a single piece of rolling luggage—just the latest casualty in the rotating cast of Donbass leadership. The unlucky ones die mysteriously. The lucky ones, like Plotnitsky, just go into a kind of witness protection program, disappearing into the belly of Russia.