Photograph by Annie Hylton

Months went by before the bodies were moved from where they had fallen in the church. They had been shot, butchered, and stabbed while seeking refuge from the war raging outside the confines of the sanctuary in which they hid.

It was a Sunday in July 1990. Peterson Sonyah spent the day like the many that came before it, inside the compound of Saint Peter’s Lutheran Church, in Sinkor, Monrovia. In spring of that year, as fighting intensified, Sonyah and his family thought they had found safety in the church, along with approximately two thousand displaced civilians. The Red Cross had designated it a humanitarian-aid center, placing banners across the compound and at the entrance.

Sonyah woke up that Sunday morning and attended a prayer service in the church. Afterward, workers and volunteers handed out cornmeal to Sonyah and the other residents. They had only one meal that day, he recalled, as the compound had run out of rice, which was usually served as their second meal. After eating, Sonyah played outside in the compound and read the Bible. He remembers his father warning him not to stray too far. “Always be with me,” his father said.

“Daddy, I’m not going to leave here,” he responded. “I will always be close to you.”

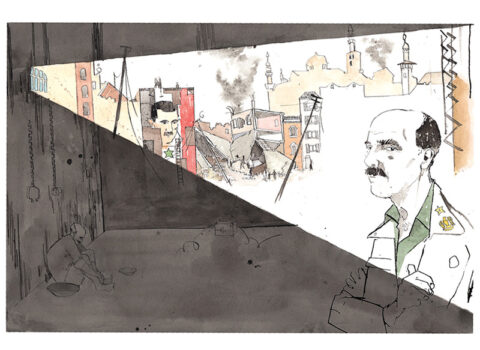

In the days leading up to this particular Sunday, government soldiers had seen women and children cooking and washing clothes in front of the church, and reassured them that they would be safe. President Samuel K. Doe had imposed a citywide curfew of 6 pm, and civilians who stepped outside after that time would be shot on the assumption that they were rebels. Government forces could have gunned down many of the residents—of the Mano and Gio peoples—at any time, a result of ethnic tensions, so some people remained crammed inside the compound all day, every day.

That evening, Sonyah lay on top of his clothes under the pew where his father slept. Many of the women and children, including Sonyah’s mother, brother, and sister, slept in an adjoining school building. As the civilians attempted to rest, roughly forty-five men from the anti-terrorist unit of the government’s armed forces burst in with assault rifles and machetes and began a killing spree, shooting and hacking indiscriminately. They raped some of the women before killing them. Several hours passed before they’d finished, by which point dawn had broken and an estimated six hundred people had been eviscerated.

In October, volunteers gathered to bury hundreds of bodies in mass graves around the church’s grounds. Sonyah’s father, under whose body Sonyah hid during the massacre, was placed in one of the graves, but Sonyah doesn’t know precisely where.

Nearly three decades since the instigation of the war, Liberia has not yet prosecuted a single individual for war crimes, including those responsible for the murder of Sonyah’s father and other civilians in the church. Some of the Lutheran church survivors may finally see their day in court—not at The Hague, but in a US civil trial brought against Moses Thomas, a Philadelphia resident who the plaintiffs claim is one of the men responsible for the attack. This case is among a handful of lawsuits filed against Liberians residing in the United States, some of whom live among their victims. The importance of these international cases for Liberians cannot be overstated: calls for justice have been at last resurrected.

And while dozens of Liberian civil-war survivors I spoke to may not live to see justice delivered, several told me that, for the first time in recent memory, they feel hope. For the man who lost his leg, the woman who was raped and made a widow, and the boy who grew up fatherless, the hope that tomorrow might be different is what makes today bearable.

Sonyah was a teenager when, in 1989, Liberia was plunged into back-to-back civil wars that would last fourteen years, take the lives of more than 250,000 people, and decimate the country. But the complicated conditions for this violence had been fomenting for nearly two centuries. In 1821, freed American slaves settled on the western coast of Africa in a geographical area roughly the size of Tennessee, now Liberia. The settlers, known as “Americo-Liberians,” made up less than five percent of Liberia’s population but they and their descendants dominated its politics until 1980. These settlers degraded the identity and status of native Liberians by denying them rights, coercing them, surreptitiously, to adopt English names, and imbuing their culture with Western traditions. As the 2009 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Liberia’s final report stated, this ethnic-based hierarchy of governance and society—funded by the American Colonization Society—was one of the primary causes of the civil wars.

In 1980, Samuel K. Doe, then twenty-eight years old and a member of the Krahn people was involved in a violent coup with a motley crew of soldiers who overthrew the Americo-Liberian government and replaced it with a military junta known as the People’s Redemption Council. Once in power, Doe severed all ties with the Soviet Union, and money flooded in from the US government; from 1980 to 1985, Liberia was the largest per-capita recipient of US aid in the sub-Sahara. Washington touted Doe as a democratizing force in the continent, despite his administration’s human-rights violations against the Mano and Gio.

In December 1989, the National Patriotic Front of Liberia, a group of rebels led by Charles Taylor (a US-educated warlord of the Americo-Liberian elite who would later become president of Liberia), began an offensive from the Ivory Coast to overthrow Doe, marking the start of the first civil war. Doe’s torture and execution by the rebels was caught on camera just months later: to demonstrate that Doe was not protected by powerful black magic, rebels cut off his ears before killing him, and then exhibited his naked, mutilated body in the streets.

Roughly a decade after the massacre, Moses Thomas fled Liberia for the United States, where he applied for political asylum. While Thomas was denied asylum, he received immigration status, allowing him to settle in the suburbs of Philadelphia, where he began serving palaver stew, cassava, and greens-based soups at a West African restaurant called Klade’s.

The truth commission’s final report named nearly one hundred individuals for “gross human-rights violations and war crimes,” including Thomas for his alleged role in the Lutheran church massacre, and recommended that Liberia set up an extraordinary criminal tribunal to investigate and prosecute war crimes, much like neighboring Sierra Leone had done for atrocities committed during its civil war. But several high-level government officials could have been implicated in the proposed trials, such as then president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who the commission recommended be sanctioned and barred from public office for her support of Taylor. “The TRC report has a lot of good things in it,” Sirleaf told reporters in 2010. But, she said, “if you were to take fifty-something persons and put them in a war crimes court today, I don’t know what would happen in terms of our peace.” Throughout Sirleaf’s tenure, demands for justice went unanswered, and the commission’s final report and accompanying documentation now sit in Georgia’s Institute of Technology. In 2011, the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded Sirleaf the Nobel Peace Prize, which she shared with Leymah Gbowee and Tawakkul Karman.

The impunity that reigns in Liberia has motivated some victims to work with investigators and attorneys to file suits in international jurisdictions where alleged human-rights abusers live. (Cases against Liberian war criminals are currently in courts in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Belgium, France, and the United States; more are forthcoming.) Yet this wasn’t the only issue working against those who survived the Lutheran church massacre. “A lot of witnesses died, and we spent years trying to piece together the individual perpetrators,” said Nushin Sarkarati, a senior staff attorney at the Center for Justice and Accountability, a California-based human-rights organization representing plaintiffs in the US civil suit. (Global Justice and Research Project in Liberia and its Geneva-based sister organization, Civitas Maxima, co-investigated the case.)

Four citizens of Liberia brought forth the lawsuit against Thomas in February 2018. (The plaintiffs have chosen to remain anonymous due to fear of reprisal against themselves or family members still in Liberia.) They are suing Thomas for damages under two unique US federal statutes that permit foreign victims of certain human-rights violations to use US courts for civil suits—the Alien Tort Statute and Torture Victims Protection Act. In compliance with the United Nations Convention Against Torture, the United States enacted legislation in 1994 that allows the prosecution of individuals who commit torture overseas but reside in the United States. This law is so rarely used that most of the charges brought against alleged perpetrators are for immigration fraud. In this case, because the massacre occurred in 1990, and the 1994 law does not apply retroactively, the plaintiffs are seeking compensation for Thomas’s alleged role in extrajudicial killing, torture, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

Thomas has denied his involvement in the massacre, asserting that his accusers have the wrong man. “It’s all lies,” he said in an interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer. “The stuff they’re talking about is nonsense. You can call anyone in the Republic of Liberia and give them my name, and they will tell you that this is nonsense.” (Requests to interview Thomas through his attorney, Nixon Kannah, have not been answered.)

A day after the lawsuit was filed, a Yelp user named D.S., of Berkeley, California, left a review of Klade’s restaurant: “This is a tough call. On the one hand, this restaurant, owned by Moses Thomas, serves up palm butter soup and cassava leaf. Yum! On the other, as reported by The Guardian, ‘according to legal papers filed in a federal court on Monday, Thomas’s carefree lifestyle masks his true identity as a bloodthirsty warlord behind some of the worst atrocities of Liberia’s civil war, including the Lutheran Church massacre.’ So, two stars?”

Recently, Sonyah took me to visit the church where he lost his father. The humidity was heavy that afternoon; the monsoon rains had momentarily cleared, leaving a cloud of steam. Sonyah, who is slender but has a round, childlike face, wore jeans with a pale-yellow shirt. When he approached the compound, he passed women in colorful lappa (long wrap skirts) with bags of cassava, corn, and potatoes perched on their heads. Across the street, manicured palm trees surrounded one of Liberia’s upscale hotels, where tourists, diplomats, and aid workers stay for roughly $300 per night.

These days, most traces of the massacre have vanished, with a few notable exceptions. Sonyah pointed out two white stars painted on sections of the compound’s concrete floor—one of the stars was partially concealed by cars, as it covers the church’s parking lot, and the other is part of a basketball court, where teenagers were shooting hoops. “Those are mass graves,” Sonyah said, as he walked around to the back of the compound. A third mass grave, covered in weeds and trash, is not marked. “My father’s body was dumped among bodies that were buried in the mass graves,” he said.

Sonyah opened the door of the church. It was eerily quiet, and the bloodstains that once coated the floor were replaced with short wine-colored carpet. Sonyah walked inside and passed bullet holes that marred the walls of the building. Light streamed in from the blue-tinted windows as he sat down on the pew where he’d slept that Sunday in 1990. He faced the altar—on which stood a cross made from artillery shells—where bodies once hung. “When they were firing too much, my father came down on the floor and covered me,” he said. “That’s when he sustained bullet wounds.”

Some victims disguised themselves beneath corpses while the men stabbed their family members, making certain there were no living among the dead. When the soldiers retreated, Sonyah’s father was still breathing. Sonyah dashed behind the church to get water, but dead bodies had been thrown in the well, and it was flooded with blood. When Sonyah returned to his father, he was dead.

The election of a new president—the former professional football player George Weah, who is said to have had no connection to the war—in December 2017 has renewed demands, including by US officials, for the implementation of the commission’s recommendations. In its first-ever review of the human-rights situation in Liberia, the United Nations Human Rights Committee said it “regrets the very few steps taken to implement the bulk of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommendations of 2009.” It also expressed “concern that none of the alleged perpetrators of gross human-rights violations and war crimes mentioned in the report, have been brought to justice, and that some of those individuals are or have been holding official executive positions, including in the government.”

It remains an open question whether President Weah will heed the calls of Liberians, who have been marching in the streets, petitioning the government, and advocating for survivors. Sonyah’s phone rings nonstop, and he is regularly plotting his next steps to get his government to initiate a special tribunal. Through his work as the executive director of the Liberian Massacre Survivors Association, he has identified dozens of mass graves around Liberia in the hopes that, eventually, someone will take action. In his downtime, Sonyah houses and feeds survivors at his modest home on the outskirts of Monrovia.

As we walked outside the church, Sonyah was somber. Nearly thirty years after he’d slept under that pew with his father, he said he has “not yet” found closure. While he doesn’t believe the case in the United States against Thomas will resolve anything for him, he feels it will deter future massacres. “So that what happened, it won’t repeat.”