Liberty and the Marketplace

Liberty vs. Rutgers, SHI Stadium, Piscataway, New Jersey, on October 26, 2019. All photographs by Brice Particelli

Ninety dancers and cheerleaders were on the field, with at least as many band members in the stands, all working to get Rutgers fans up and moving. The bass was pumping between plays, shaking our seats as the JumboTron’s cameras searched the crowd for students dancing on bleachers or older alumni pumping their fists atop portable cushions. There wasn’t much to see. SHI Stadium was only half full. But even with a scant crowd, there was a party atmosphere. Everyone was wearing red hats, T-shirts, and jerseys, including fans from the opposing team, Liberty University, whose official seal is a burning book alongside the motto “Knowledge Aflame.”

Rutgers is a six-hour drive from Lynchburg, Virginia, so the Liberty players had only a vocal parents’ section and scattered alumni and friends to cheer them on. Despite the meager turnout, this was a big game for Liberty, in a big year. It was the institution’s first full season in the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS), the highest level of college football, and the evangelical school had made some questionable hires to guarantee success.

Liberty’s president, Jerry Falwell Jr., brought in Hugh Freeze as head coach for the 2019–20 season, just months after Freeze had been forced out at the University of Mississippi. In five seasons at Ole Miss, Freeze had taken the Rebels from a midlevel bowl team into the top five, culminating with a high-profile win at the 2016 Sugar Bowl. His rise had ended spectacularly when his staff was caught fixing ACT scores and handing out cash to their football recruits. The NCAA expunged twenty-seven of the team’s wins, and an investigation revealed that Freeze had been making calls to an escort service using his school cell phone.

Two years earlier, Falwell had also hired Ian McCaw, who’d been forced to resign after thirteen years as Baylor’s athletic director. McCaw was accused of ignoring allegations of sexual assault against the football team for years, posing “a risk to campus safety,” Baylor’s investigation found. Amid the investigation, Falwell tapped him to lead his university’s men’s and women’s sports programs.

These hires were calculated risks, weighing the well-being of students against a grander scheme. Liberty’s rise in athletics could mean power and prestige, and FBS football is a lucrative centerpiece. They were joining teams like the University of Texas and Ohio State that command tailgates and television screens every weekend, building brands that elevate their sports programs to $200-million-a-year empires. McCaw and Freeze knew how to make the most of this profitable industry. In the FBS, large amounts of money change hands, even over the smallest things—for instance, Rutgers had paid Liberty $1 million to play in New Jersey, a contest the Lynchburg school knew it would almost certainly lose. The previous season, Rutgers had won only one game. They needed a victory.

Liberty lost to Rutgers that day, but that was okay—it was expected. It was scheduled.

Walking out of the stadium, one Liberty fan consoled another. “It’s early,” he said. “We don’t have that Big Ten kind of money yet. Give us a couple of years.”

That kind of money has begun to arrive. Since taking over in 2007, Falwell has transformed Liberty from a small fundamentalist school flirting with bankruptcy into one of the largest universities in the country, commanding a $1.6 billion endowment. With approximately 15,000 resident students and 100,000 online, Liberty competes with corporate entities like the University of Phoenix that have benefited from deregulation of online education enacted during the Trump presidency.

And it continues to grow. While Liberty’s curriculum—from its business program to the medical school—teaches that long-established scientific theories like evolution are wrong and that the universe is no more than ten thousand years old, enrollment has increased tenfold since 2008. The school has become a leader in online education, and it’s by far the largest university with a football team in the FBS.

Liberty’s growth has not been without controversy. The school’s unofficial motto is a quote from founder Jerry Falwell Sr.: “If it’s Christian, it ought to be better.” Yet Jerry Jr.’s miraculous expansion of his father’s institution has often strayed from that dictum. The past three years have seen mounting accusations that Jerry Jr. has led the university with heavy-handed opportunism, offering financial benefits to friends and family and silencing students and staff who speak up.

While this may sound somewhat routine for an evangelical establishment of its size—parochial problems for Falwell’s flock to grapple with—Liberty has also provided Jerry Jr. with the opportunity to influence national politics.

Just a week after Trump’s stumbling “Two Corinthians” speech at Liberty, where Trump exposed his unfamiliarity with the Bible, Falwell offered Trump his campaign’s first major evangelical endorsement. It set off a whirlwind of denunciations from other religious groups, but the community fell in line by the time the GOP convention rolled around. There, Falwell described Trump as “America’s blue-collar billionaire,” and suggested that his presidency would lead to “a huge revolution for conservative Christians.” Even after the Access Hollywood tape exposed Trump bragging about sexual assault, Falwell remained a vocal campaigner. His early support is often credited with the outcome of the 2016 election, with 81 percent of white evangelicals voting for Trump.

Falwell justified his support as emblematic of Christian forgiveness, but the real reason went deeper. In 2018, Liberty produced The Trump Prophecy, a docudrama that promoted the popular evangelical idea of Trump as a “King Cyrus” leader: an imperfect strongman who nonetheless contributes to the greater good. Like the brutal and nonbelieving Cyrus described in the Bible, whose regime was aided by God to allow the faithful to return to Jerusalem, the hypothesis is that God is guiding Trump’s hand to extend His kingdom. A little pain for some is worth it, the reasoning goes, as long as it leads to a heavenly expansion. Comparisons to Cyrus originated with religious broadcasters in the lead-up to the election, bolstered by the coincidence that Cyrus is described as “anointed” by God in Isaiah 45 and that Trump is the forty-fifth president.

When Falwell set his sights on expanding Liberty’s kingdom into the NCAA, he chose two Cyruses to lead the way. Under the leadership of McCaw, Liberty prevailed in its first March Madness basketball game, in 2019. And though Rutgers had won on the football field that fall, it was Liberty that made it to a bowl game. Thanks to strategic scheduling, Liberty was offered a spot on CBS Sports at the mid-level Cure Bowl, which purports to support women’s health while earmarking just $50,000 of its proceeds for donation.

Taking the field as the underdog, Liberty exceeded expectations. It won, 23-16, earning a gold trophy, a victor’s purse of $573,125, and the eager eyes of the millions of sports fans who tuned in, wondering about this new school in the FBS.

The NCAA, game schedulers, sports writers, and fans who participate in this multibillion-dollar-a-year industry have largely ignored McCaw’s and Freeze’s new roles, and they’re left undiscussed outside college sports. Yet NCAA games can offer legitimacy, recruitment opportunities, and a deeper connection to alumni. They also boost profits and enrollment. Harvard researcher Douglas Chung found that when a college team “goes from being mediocre to being great on the football field, applications increase by 17.7 percent.” The biggest jump was among schools with low academic rankings; one school’s applications doubled after its team was televised regularly.

As Liberty continues its rise, there have been increasing concerns, both within the institution and outside it, that no one is paying attention to how Falwell is building what seems destined to become the largest university in America.

So far, the school’s role in televised sports has raised only passing concerns, like when ESPN commentator Bill Walton called it “an unremovable stain” on UCLA that the Bruins had scheduled a game against Liberty. Asked why, he responded, “If you don’t know the history of Liberty, just go look it up.”

Walton’s objection was probably directed at founder Jerry Falwell Sr., an evangelical pastor who preached against Martin Luther King Jr. and believed that desegregation “will destroy our race eventually.” Falwell made his first foray into education in 1967 with the founding of Lynchburg Christian Academy, which was announced in the local paper as “a private school for white students.” Four years later, after his popular Old Time Gospel Hour radio show became a nationally syndicated TV program, Jerry Sr. founded Liberty as a private evangelical college with 154 students. In 1979, he launched the Moral Majority to harness political power, and with an early endorsement of Ronald Reagan, he became a kingmaker. His influence only grew as he led battles against the Equal Rights Amendment, abortion, LGBTQ rights, and the teaching of evolution. He never softened, notoriously claiming that gay people deserved AIDS and that God allowed 9/11 to happen because it was “what we deserve.”

When Jerry Sr. died in 2007, his empire was split between his two sons. The youngest, Jonathan, was given the megachurch, while Jerry Jr., who had a law degree and had done a stint in commercial real estate, got the school. Their father had always wanted Liberty to become a Notre Dame for evangelicals, but hadn’t figured out how to achieve that—either because he wasn’t willing to compromise the school’s mission to broaden its audience, or because his timing simply wasn’t right.

When Jerry Jr. took over Liberty, it was the dawn of online education. Utilizing aggressive sales techniques to access federally funded student-loan revenue—and surviving a short blip of Obama-era regulations like the gainful employment rule, which required online schools to prove their graduates had found employment—Falwell added hundreds of academic programs, with almost 90 percent of students attending online. In 2018, disillusioned staff and faculty described the online programs to the New York Times as a moneymaking scheme, offering diluted content in order to expand a financial empire at the expense of its students. Supporters describe it as evangelism—a method to get the word out faster and farther.

These two visions are not mutually exclusive. During a conversation I had with Liberty provost Scott Hicks, he equated expansion with evangelism. Liberty couldn’t grow its influence unless it built programs that incorporated fundamentalist beliefs into more majors, producing business leaders, lawyers, zookeepers, doctors, and teachers. The school is simply becoming more “focused on building marketplace Christians who want to go out and impact the marketplace,” Hicks said.

For those who follow Jerry Jr., this focus on a market-oriented takeover isn’t surprising. Falwell is a lawyer, after all, not a minister. Yet not all alumni, staff, and students have been comfortable with how Liberty’s growth has been achieved. Falwell’s administration has leaked troubling internal documents that show that he called a student “retarded,” that Liberty’s chief information officer was hired by the Trump team to rig online polls, that Falwell paid off a Miami pool boy in a scandal involving nude photos, and that Liberty might be using its nonprofit funds illegally, in the form of questionable land transfers and business contracts to benefit friends and family.

Falwell vigorously fought back against the bad press. In a series of moves that seem intended to discourage dissent, he called the FBI to investigate his own staff, asked police to issue arrest warrants for reporters who ventured onto campus, and regularly threatens journalists with lawsuits. Recent alumni have described a culture of silence on campus, including a former editor in chief of Liberty’s student newspaper, Will Young, who wrote of “a censorship regime” that included line-by-line alterations of student reporting by Falwell himself. It was part of “an infrastructure of thought-control” that overwhelmed campus life, Young asserted. While most campus governments advocate for students, at Liberty it “helped administrators enforce the culture,” Young wrote, blocking anyone who challenged Falwell’s personal politics—even stopping a student group’s statement against white supremacy and attempting to suppress a #MeToo demonstration.

While some small protests have occurred, Liberty’s restrictive honor code muzzles dissent by making nonspecific offenses like “disruption to university community,” “non-compliance with a directive,” and “conduct inconsistent with Liberty’s mission” expellable, creating a community where students’ concerns and individual voices are frequent casualties of the school’s ideological goals.

Aharown Campbell, a recent graduate and former starting lineman on the football team, described the day McCaw was hired as athletic director as one of those moments. Concerns about effects on student safety and campus culture were dismissed by school leadership, and Liberty’s coach at the time, Turner Gill, told the team to ignore the noise. “Let’s separate the politics from why we’re here. We’re here to do a job,” he said.

When the school replaced Gill with Freeze, it became even clearer to Campbell that Falwell’s vision didn’t fit in with what he thought were Liberty’s foundational values. “You don’t bring in an SEC coach who’s dirty, clean him up, and put him on a pedestal unless you’re trying to cement Liberty as a top contender,” Campbell told me.

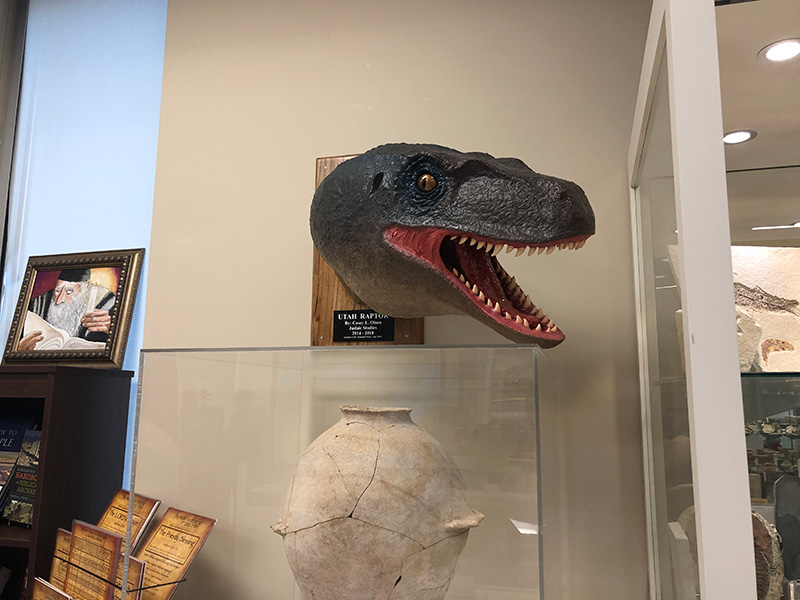

The Utah Raptor in the Biblical Museum in the Jerry Falwell Library at Liberty University

I visited Liberty in mid-August of 2019, during the first week of classes, and spoke to students about its rapid growth and shifting mission. Construction equipment was all over the 7,000-acre campus. The institution had pumped more than a billion dollars from its online programs into renovations and expansion. New, untouched buildings, all designed in grand, Jeffersonian, redbrick and white-column style, sat waiting for a final landscaping polish. The school had recently completed a $25 million upgrade of the football stadium, to attract FBS-level athletes and fans, and of its locker rooms, complete with recessed lighting to illuminate the players’ helmets, as well as a 13,000 square-foot player’s lounge.

The School of Divinity’s narrow tower looms over the campus, a phallic, redbrick building that resembles an oversize lighthouse, and holds a replica of the Liberty Bell at the top. Called the Freedom Tower, it opened in 2018, months after required credits in Christian Life and Thought were cut nearly in half (from 23 to 12) and just before a dozen Divinity faculty were laid off. The Freedom Tower’s mix of iconography seems to stand as a metaphor for Liberty’s view of the relationship between nationalism and religion: that our nation and its leaders exist only to spread religious fundamentalism.

Yet Liberty’s push into new majors, along with its rapidly expanding enrollment, has attracted students who aren’t always willing to adopt the school’s rigid moral code. Sitting over coffee on the school bookstore’s patio, overlooking a vast parking lot at the edge of campus, I chatted with a student from Liberty’s informal LGBTQ club. It’s informal because the existence of homosexuals and non-cisgender people is considered “immoral,” he told me, and clubs here require faculty sponsorship. Tenure doesn’t really exist at Liberty, the student told me, so faculty aren’t willing to stick their necks out for much. The LGBTQ club didn’t even try to find a sponsor—a few had already failed to start a Democrat club, after a faculty member decided it wasn’t worth the risk to identify himself as supportive of their cause.

The culture is slowly shifting, the student told me, as enrollment grows and students push against the rules. But while certain aspects of campus life, such as the dress code, have relaxed, the fundamentalist rules remain largely intact. Liberty once openly embraced so-called “conversion therapy,” in which an LGBTQ person is counseled to “convert” to heterosexuality. Now, if the administration learns that a student is LGBTQ, they might be sent to one of the LU Shepherds—“counselors on campus who teach people to suppress or deny,” he explained—or encouraged to join the Armor Bearers, a group of men who discuss their struggles with sexuality. Both of these approaches fit GLAAD’s definition of conversion therapy, but could, according to only the loosest interpretation, be considered a kind of easing.

The student’s suggestion that “it’s not as bad as it used to be” surprised me. His ambivalence turned to sadness only when he related that he’d felt unable to date publicly during his four years there, for fear of being outed to the administration. Repercussions could include fines, mandatory counseling, and even expulsion.

When I asked if he thought Liberty’s curriculum was secularizing, given the recent trimming of required fundamentalist courses, he offered a quick “No.” Creationism, anti-evolution, anti-LGBTQ, and fundamentalist beliefs were embedded in every biology, psychology, and history class, he said, and the administration keeps a tight lid on student and faculty voices. While some surface-level rules might be relaxed, Liberty will always be a fundamentalist school. “I don’t think Liberty will ever change” he said. “Not really.”

Most of the football players I talked to agreed. “The changes to the university are merely for looks,” offered Liberty wide receiver Sean Queen. “God is still the center of the campus.”

Safety Cade Robinson agreed. “By loosening rules, we opened the door for more unbelievers who were once drawn away from attending,” he said. “We believe in bringing in an individual and dive into them when they arrive.” The team is a brotherhood, players told me, a family that closes every practice hand-in-hand in prayer, and newcomers quickly fall in line.

For the most part, the students I spoke with saw Liberty as an oasis of truth in a conflicted world, and their worries were less about the mission than the strategy. Even on campus, Falwell is a controversial character, and several expressed unease that the administration seemed less concerned about students than with making the school appear successful. A biology student worried that Liberty was ignoring the upkeep of research equipment, and that the school would fill its newly constructed buildings with students but be unable to teach them properly. A student-government leader worried that the administration was ignoring a growing mental health issue—an uptick in reports of loneliness and isolation on campus. He lamented the time spent reacting to Falwell’s theatrics, and the money spent on buildings and sports, rather than on developing a healthier community for its students. Growth was good, he said, every organization wants to extend their reach, “but it matters how you get there.”

Liberty vs. Rutgers, SHI Stadium, Piscataway, New Jersey

Liberty has continued its nationally televised rise. On March 8, 2020, on ESPN, the men’s basketball team won a second consecutive conference championship, once again securing a March Madness spot. But on March 11, with COVID-19 having spread to 114 countries, the WHO declared the coronavirus a global pandemic. The next day, the NCAA canceled the March Madness tournament and Falwell went on Fox and Friends to denounce the closures and cancellations as a Democratic hoax. “Impeachment didn’t work, and the Mueller report didn’t work, and [the 25th Amendment] didn’t work, so maybe now this is their next attempt to get Trump,” he said.

Falwell promised to reopen campus after spring break, even as Liberty’s classes were forced online by state health guidelines. Students should be able to “enjoy the room and board they’ve already paid for and to not interrupt their college life,” Falwell said.

It didn’t go well. As students returned from spring break, some brought the virus with them (and Liberty sued reporters for reporting it). As worries spread, many wondered why Liberty hadn’t offered to refund room and board, allowing students to find housing elsewhere, as other universities did. One Liberty parent, Jeff Brittain, tweeted to Falwell: “I’m as right wing as they get, bud. But as a parent of three of your students, I think this is crazy, irresponsible and seems like a money grab.”

As scrutiny heightened amid the confluence of the coronavirus and anti-racist protests, Falwell posted a racist image to mock the Virginia governor’s face mask requirements. Thirty-five prominent African-American alumni, including pastors and pro football players, wrote an open letter calling for Falwell’s resignation, and several African-American faculty and staff members resigned in protest. Among them was LeeQuan McLaurin, the school’s director of diversity retention, who stated, “I can not just be a window dressing on what is clearly an institution that struggles with a history of racism, prejudice, and discrimination.”

Throughout June and July, recruits and players across multiple sports split from the university, including two star football players, cornerbacks Tayvion Land and Kei’Trel Clark. Land wrote, “Due to racial insensitivity displayed by leadership at Liberty University, I have decided to enter my name into the transfer portal and no longer be a student-athlete at Liberty.” Clark described a school plagued with cultural incompetence “within multiple levels of leadership.” He could not continue to play for Liberty, he said. “This decision is simply bigger than football.”