Lemon Zest

This past February, thousands of lemons and oranges went on display in Menton, a quiet town on the French Riviera. Citrus lined its main street like tiny, edible cobblestones. In front of a beachfront casino, the city had erected a monumental wall of lemons; on the other side was a miniature yellow Buddhist temple followed by eleven more sculptures made entirely of fruit, each the weight of nine cars. The citrus was arranged so precisely that, from a distance, it looked like a coat of paint.

City officials wandered the wide avenue looking intently at the fruit. After a few days in the hot sun, the sculptures had to be checked for mold at least twice a week, particularly near the top. The parks director circled a leprechaun made of lemons and oranges. He approved the glossy yellow shamrocks and the orange pot of gold, then climbed a ladder to inspect the next design. The Day of the Dead skeleton looked fresh except for the wide brim of her hat, which had started to spoil.

A few days before the festivities began, the squished oranges were cleaned off the pavement, and the last polystyrene heads were lifted by a crane onto their respective bodies. There was a temporary wall to conceal the citrus from the street, but it was not quite tall enough. Passersby could glimpse the turrets of a castle made of neat lemon spirals, and an enormous German man floating amid the palm trees, dressed in orange lederhosen.

No one on the street seemed particularly interested in the spectacle; it was, after all, Menton’s eighty-seventh lemon festival. After the citrus dragons for 2015’s Tribulations of a Lemon in China and the snake charmers for 2018’s Bollywood, the exoticizing Festivals of the World theme of 2020 seemed routine. The locals knew that ten citrus floats would appear in time for the weekend parade. There are agricultural festivals all over the world, from Californian almond fairs to the Italian Battle of the Oranges, but none quite so reliably extravagant as the Fête du Citron.

The lemon éclairs, lemon-shaped bars of soap, lemon-scented perfume (Eau de Menton), and other local specialties naturally imply that the fruits here are homegrown. There were so many lemons—piled in the windows of a McDonald’s, adorning the city crest—that even the standard yellow mailboxes and crosswalks seemed deliberately color-coordinated.

But the fruit, it turned out, wasn’t local—this year, the lemons came from Spain. They were grown in an industrial orchard in Valencia, Menton’s sister city, where an automated system selected the most uniformly shaped fruit. The symmetrical orbs were packed into lemon-patterned boxes and treated with an artificial wax to preserve their color. A few days later, they arrived in Menton, yellow as ever. City officials arranged the crates under large white tents, spaced like guests at a garden party. There, the air circulation kept the ethylene gas naturally emitted by the lemons from prematurely ripening the fruit.

That they were imports wasn’t publicized, but it wasn’t hidden, either. There had been a public call for bids to fulfill the order, and festival officials tended to address the hundred-thousand-euro expense like any other logistical detail.

Jean-Claude Guibal, the seventy-nine-year-old mayor of Menton, did not seem concerned that the lemons weren’t from Menton, or even from France. “The festival is colorful, it’s of the people,” he told me. In any case, he explained, “we need one hundred and eighty tons of lemons, and you can only find that in Spain.” The image of the city is dear to him; he had recently prohibited the installation of solar panels because they would disrupt the terra-cotta skyline. His office smelled of cigar smoke and salty air, and had been painted with a mural of a lemon harvest. On the wall behind his desk, young women in long skirts gathered the loosely sketched yellow shapes under a soft afternoon light.

Last year, the French Ministry of Culture admitted the Lemon Festival into its inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage, where it took its place alongside falconry (2016) and the French school of mime (2017). It’s recognized as a cultural practice that offers “a sense of identity and continuity.” The city hopes to receive the same award from UNESCO next. “It’s become a festival with an international reputation,” Guibal, who has held his office for over thirty years, said. “Everywhere I go, in France and in the world, when I say that I’m the mayor of Menton, people say, ‘Oh yes, the lemon festival.’”

A photograph of the 2019 festival’s lemons in crates, taken by the author.

From the fourteenth to the nineteenth centuries, the cultivation of lemons was inextricable from Menton’s economy and laws. The town was acquired by the Principality of Monaco in 1346, and soon began to grow more lemons than wheat. The royal family made a fortune on Menton’s citrus. A Monegasque prince executed the first recorded sale of a Menton lemon in 1495: two golden ducats’ worth of “orange apples.”

Monaco protected its lucrative fruit with various edicts. In 1671, the royal family appointed eighteen lemon magistrates to oversee the citrus trade. The magistrates controlled the price of the lemons, and verified the diameter of each fruit before it was sold. Undersized specimens were sent to fabric dyers and perfumeries. The “police of the lemons” ensured the safety of the town’s groves: it was a crime to pick the flowers from the trees or wear shoes in their vicinity, for fear of damaging the roots. (Lemon thieves and sellers of poor-quality fruit faced corporal punishment; recidivists faced indentured servitude.)

By the early nineteenth century, the golden age of the “golden fruit,” the region had about eighty thousand lemon trees. It was the world’s northernmost producer; any lemons in Saint Petersburg or Amsterdam were likely from Menton. Monaco’s princes continued to tax the exports heavily. The tariff financed their neoclassical pink summer palace and, eventually, fueled popular support for the city’s secession, in 1848.

In the 1870s, tourism began to overtake lemon production as the region’s main industry. An English doctor, James Henry Bennett, prescribed “winter and spring on the shores of the Mediterranean” in his book of the same name, citing the “blueness” and “saltiness” of the sea as a cure for tuberculosis. The area’s lenient winters, ideal for citrus groves, were just as attractive to consumptive European aristocrats. In the following years, the cemetery above Menton filled with Russian Orthodox crosses and tombstones bearing English epitaphs.

For visitors seeking less eternal stays, forty-five grand hotels opened in the following decades. In town, there was an English pharmacy and a shop selling caviar. Lemon groves were ceded to hoteliers, who occasionally hired the citrus farmers as construction workers. These Belle Époque palaces, with gilded cupolas and bow windows offering views of the sea, housed thousands of guests, many of whom furnished their suites with their own beds, dressers, and wallpaper.

By the 1920s, though, it had become difficult to keep the aristocrats in Menton. Hotels that once served as military hospitals only partially recovered their clientele. The city also had to compete with ski resorts and new Côte d’Azur attractions. Hoteliers organized afternoon tea, performances by Isadora Duncan and Maurice Chevalier, and ice skating with orchestral accompaniment. Finally, in 1928, one hotel manager proposed a display of citrus fruit in gold and silver wicker baskets: fresh produce was the new antidote for the tedium of paradise.

Winter is no longer Menton’s tourist season (it’s referred to as the “hollow period” in French). The old tuberculosis sanatorium, a stately turn-of-the-century building in the hills, is now a center for cardiorespiratory health. The Winter Palace Hotel lobby, once full of card tables and rattan sofas, is a spare apartment-building foyer. Nearby, the ballroom of the Grand Hotel des Iles Britanniques was partitioned into two floors and converted into apartments; its ornate frescoes are now someone’s bedroom ceiling.

But the wicker baskets were never repurposed. Each year, more than 240,000 people travel to Menton for parades with titles like Party Time for the Lemon and Tintin Comes to the Land of Lemons. The festival now has the particular distinction of being “the third most popular event in the Alpes-Maritimes.”

Although the festival was founded to showcase the Menton lemon, the town only produced enough of them for the first few decades of its existence, for sculptures like the Queen of the Golden Fruit in 1935 and the World Peace Globe in 1949. In the 1950s, frosts destroyed the few groves that had survived the region’s development and rural exodus. Those that remained were “cursed” with mal secco, a disease that infects Mediterranean citrus. A handful of the trees remained in private gardens, but commercial production was over.

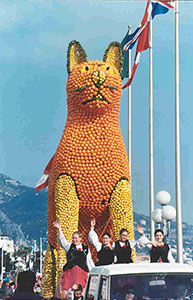

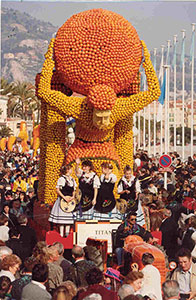

Theme: “Menton Monaco: Une Histoire de Princes” (Menton-Monaco: A Story of Princes), 1997

Still, Menton had its tradition and an expectant audience; the fruit was merely a formality. In 1956, they celebrated its agricultural bounty with another town’s lemons (and without any apparent concern over the illusion—the theme of that year’s festival was Abundance). Every winter for the next few decades, the lemons arrived from Italy, North Africa, and, in the 1980s, Florida and Israel. By then, the point was to perform the Menton lemon rather than to display it. Any spoiled fruit was coated in spray paint.

The festival’s floats are now built in a former slaughterhouse, the only structure tall enough to accommodate them. The work starts in September, after the marketing office decides on the year’s theme. Artisans in Menton collaborate with a company in Nice run by a fourth-generation family of carnavaliers. Together they design the metal frames, often with a preference for complex volumes that showcase craftsmanship: a Ferris wheel, a geisha’s kimono, Venetian carnival masks.

Come January, city employees from various departments are temporarily reassigned to the warehouse. They stand on ladders or scaffolding, wearing harnesses and hard hats, to attach fruit to the metal frames. A yellow rubber band is looped through the wire mesh and around each lemon. The process is called fruitage, an invented term that also comes with its own verb, fruiter, or “to fruit.” “The oranges are easy, since they are so symmetrical,” a secretary in the urban planning office told me. For a neat row of lemons, she explained, you have to twist each one until it’s perfectly flush with the rest.

On the day of the parade I witnessed, the floats were wheeled to the end of the promenade before dawn as festival workers lifted low-hanging power lines out of the way. Tour guides led people to bleachers with poles topped by plastic lemons and tennis balls. John Lemon, a human-size mascot, received hugs and posed for photos at the entrance to the stands.

Theme: “Menton Monaco: Une Histoire de Princes” (Menton-Monaco: A Story of Princes), 1997

At two-thirty, a giant citrus Chinese New Year dragon began to glide down the block. The rest of the floats followed in slow unison, colorful international clichés that shot confetti into the bleachers and onto the pebble beach. As the parade wore on, the attraction became the handiwork that went into the floats rather than any particular motif. Watching the procession, it was hard not to think about how the city had allocated 20,000 hours’ worth of municipal wages to create a huge lemon parasol, among other structures, or that it had purchased some 750,000 yellow and orange rubber bands from Taiwan.

The festival planners must know that it’s difficult to remain enthralled by objects that move so slowly, however whimsical their form, because marching bands and children in a variety of traditional costumes had been dispatched between the floats. There were Rio carnival dancers, stilt walkers, and a great many men in medieval tights.

The parade is barely profitable, but city hall is committed to its annual spectacle. Many local businesses benefit greatly from the influx of tourists. It’s also an exercise in civic identity—year after year, the extravaganza announces that Menton deserves its title of the City of Lemons. Recently, that claim has taken on a renewed legitimacy, because the festival has, in a roundabout way, resurrected the Menton lemon.

In the past year, the town harvested forty tons of local lemons. The fruit sells for five euros a kilo in the region, and as much as twelve euros in Paris. New groves dot the hills above town, though their owners don’t yet make a living wage from them. A retired Formula One driver grows Menton lemons alongside clementines, pomelos, and citrons. A father-son team produces Mentonese limoncello and candied lemon powder, which retails for ten euros an ounce.

Theme: “Mythes et légendes de la Méditerranée” (Myths and Legends of the Mediterranean), 1990

In fact, the lemon renaissance began in the 1990s. At the start of his tenure as mayor, Jean-Claude Guibal offered financial incentives to citrus growers, and planted a municipal grove. The Association for the Promotion of the Menton Lemon was founded a decade later, when there was still very little to promote. As a result of these initiatives, the number of lemon trees doubled between 2004 and 2012. Michelin-starred restaurants in Paris began ordering Menton lemons, to be made into sorbets and vinaigrettes; new orchards appeared with names like the House of the Lemon. “Menton must be surrounded by lemon trees once again,” Guibal asserted in 2015.

That work was largely in pursuit of a Protected Geographic Indication designation. The European Commission judges whether a product, such as an oyster or a pastry, is authentically regional—and, if so, who can sell it. The notion is based on the philosophy of terroir, the tangible and intangible influence of place. It suggests that while a Menton lemon or a Flemish cake can be produced and sold somewhere else, it shouldn’t be, at least not under the same name. (Tangy white sheep’s milk cheese can only be “feta” when it’s made in Greece; Danish producers, for example, call it “salad cubes.”)

The first part of the application consists mostly of exhaustive description, with a few instances of technocratic poetry. “During the period of cold winter nights, it has a bright, almost fluorescent yellow color,” reads Menton’s. The nominating country then presents its case for why the product is unique to its region. It might be the land itself—salt marshes for sea salt, caves with particular strains of mold for blue cheese—or inherited knowledge, like beekeeping or nougat-making techniques. The Menton lemon does indeed benefit from its natural setting—the sandstone, the 2,800 annual hours of sunshine, the ocean mists—but realistically, it could be grown somewhere else, by other people.

Theme: “Féeries Marines” (Marine Fantasies), 1994

Instead, Menton’s application relied heavily on historical evidence, such as the seventeenth-century lemon edicts. It also cited the Lemon Festival and its “thousands of spectators since 1934.” The argument could be considered circuitous: Is a festival made with another country’s lemons proof of anything but nostalgia? Yet other applicants have made a similar point. The file for the Loué egg notes that it once formed the basis for Loué’s economy, and the Gragnano pasta application claims that the wide streets of Gragnano were built “to facilitate the drying phase of the pasta.” The approach is not entirely disingenuous. Over the course of four decades, the imported fruit served as a kind of placeholder for the Menton lemon. In the end, Menton’s rhetorical strategies worked: the European Commission awarded Menton the Protected Geographic Indication label five years ago.

Now the festival has a stand dedicated to the certified fruit. If the lemons on the floats are smooth assembly-line copies, the Mentonese variety has all the seductive ugliness of quality. It’s pale, about the color of an omelet, and each one is a different size and shape, as if painstakingly drawn by a toddler who pressed too hard with her crayon. Some people eat the Menton lemon whole, like an apple. It’s possible—your teeth sink into the rind deeper than expected, with your tongue pressed against the leathery rind, and then the astringent juice makes your whole mouth tart. It’s surprisingly sweet, but it’s still a lemon.

The label has put the Citron de Menton in high demand, and the orders from high-end restaurateurs and ice cream makers regularly exceed what the town can produce. In response, it recently planted five thousand lemon trees in municipal greenhouses. These will eventually be relocated, but enough suitable land must first be obtained. The lemon association is currently looking for the locations of the old nineteenth-century orchards, though it doesn’t expect to find the original irrigation systems and traditional stone terraces intact.

Last fall, a local elementary school offered to help with the search for the lost groves. A class of fifth graders is currently examining the town’s historic cadastral registers, where the economic activity of every plot of land was once recorded. Each ten-year-old is equipped with a photocopy from the municipal archives, a map, and a set of highlighters: green for olive trees, red for vineyards, blue for wells, and yellow for lemons. The students have already finished their inspection of the 1811 map which includes the area around their school. It’s almost entirely shaded yellow, including the playground.